A Review of Wood-Bark Adhesion: Methods and Mechanics of Debarking for Woody Biomass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bark Anatomy and Cell Size Variation in Quercus Faginea

Turkish Journal of Botany Turk J Bot (2013) 37: 561-570 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/botany/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/bot-1201-54 Bark anatomy and cell size variation in Quercus faginea 1,2, 2 2 2 Teresa QUILHÓ *, Vicelina SOUSA , Fatima TAVARES , Helena PEREIRA 1 Centre of Forests and Forest Products, Tropical Research Institute, Tapada da Ajuda, 1347-017 Lisbon, Portugal 2 Centre of Forestry Research, School of Agronomy, Technical University of Lisbon, Tapada da Ajuda, 1349-017 Lisbon, Portugal Received: 30.01.2012 Accepted: 27.09.2012 Published Online: 15.05.2013 Printed: 30.05.2013 Abstract: The bark structure of Quercus faginea Lam. in trees 30–60 years old grown in Portugal is described. The rhytidome consists of 3–5 sequential periderms alternating with secondary phloem. The phellem is composed of 2–5 layers of cells with thin suberised walls and narrow (1–3 seriate) tangential band of lignified thick-walled cells. The phelloderm is thin (2–3 seriate). Secondary phloem is formed by a few tangential bands of fibres alternating with bands of sieve elements and axial parenchyma. Formation of conspicuous sclereids and the dilatation growth (proliferation and enlargement of parenchyma cells) affect the bark structure. Fused phloem rays give rise to broad rays. Crystals and druses were mostly seen in dilated axial parenchyma cells. Bark thickness, sieve tube element length, and secondary phloem fibre wall thickness decreased with tree height. The sieve tube width did not follow any regular trend. In general, the fibre length had a small increase toward breast height, followed by a decrease towards the top. -

1 Wound Healing and Hyper-Hydration

University of Huddersfield Repository Ousey, Karen and Cutting, Keith Wound healing and hyper-hydration - a counter intuitive model Original Citation Ousey, Karen and Cutting, Keith (2016) Wound healing and hyper-hydration - a counter intuitive model. Journal of wound care, 25 (2). pp. 68-75. ISSN 0969-0700 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/27031/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Wound healing and hyper‐hydration ‐ a counter intuitive model Abstract: Winters seminal work in the 1960s relating to providing an optimal level of moisture to aid wound healing (granulation and re‐epithelialisation) has been the single most effective advance in wound care over many decades. As such the development of advanced wound dressings that manage the fluidic wound environment have provided significant benefits in terms of healing to both patient and clinician. -

The Role of Carbonic Anhydrase in the Modulation of Central

THE ROLE OF CARBONIC ANHYDRASE IN THE MODULATION OF CENTRAL RESPIRATORY-RELATED PH/CO2 CHEMORECEPTOR-STIMULATED BREATHING IN THE LEOPARD FROG (RANA PIPIENS) FOLLOWING CHRONIC HYPOXIA AND CHRONIC HYPERCAPNIA by Kajapiratha Srivaratharajah A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Graduate Department of Cell and Systems Biology (Zoology) University of Toronto © Copyright by Kajapiratha Srivaratharajah (2008) The Role of Carbonic Anhydrase in the Modulation of Central Respiratory-Related pH/CO2 Chemoreceptor-Stimulated Breathing in the Leopard Frog (Rana pipiens) Following Chronic Hypoxia and Chronic Hypercapnia Kajapiratha Srivaratharajah Master of Science Graduate Department of Cell and Systems Biology University of Toronto 2008 ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis was to elucidate the role of carbonic anhydrase (CA) in the modulation of central pH/CO2-sensitive fictive breathing (measured using in vitro brainstem-spinal cord preparations) in leopard frogs (Rana pipiens) following exposure to chronic hypercapnia (CHC) and chronic hypoxia (CH). CHC caused an augmentation in fictive breathing compared to the controls (normoxic normocapnic). Addition of acetazolamide (ACTZ), a cell-permeant CA inhibitor, to the superfusate reduced fictive breathing in the controls and abolished the CHC- induced augmentation of fictive breathing. ACTZ had no effect on preparations taken from frogs exposed to CH. Addition of bovine CA to the superfusate did not alter fictive breathing in any group, suggesting that the effects of ACTZ were due to inhibition of intracellular CA. Taken together, these results indicate that CA is involved in central pH/CO2 chemoreception and the CHC-induced increase in fictive breathing in the leopard frog. -

How Does Phloem Physiology Affect Plant Ecology?

Plant, Cell & Environment (2016) 39,709–725 doi: 10.1111/pce.12602 Review Allocation, stress tolerance and carbon transport in plants: how does phloem physiology affect plant ecology? Jessica A. Savage1, Michael J. Clearwater2, Dustin F. Haines3, Tamir Klein4, Maurizio Mencuccini5,6, Sanna Sevanto7, Robert Turgeon8 &CankuiZhang9 1Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, 1300 Centre Street, Boston, MA 02131, USA, 2School of Science, University of Waikato, Hamilton 3240, New Zealand, 3Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts, 160 Holdsworth Way, Amherst, MA 01003, USA, 4Institute of Botany, University of Basel, Schoenbeinstrasse 6, 4056 Basel, Switzerland, 5School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, Crew Building, West Mains RoadEH9 3JN Edinburgh, UK, 6ICREA at CREAF, Campus de UAB, Cerdanyola del Valles, Barcelona 08023, Spain, 7Earth and Environmental Sciences Division, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM 87545, USA, 8Plant Biology Section, School of Integrative Plant Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA and 9Department of Agronomy, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA ABSTRACT potentially influencing everything from growth and allocation to defense and reproduction (Fig. 1). The phloem’srolein Despite the crucial role of carbon transport in whole plant shaping many ecological processes has intrigued scientists for physiology and its impact on plant–environment interactions decades, but proving a direct connection between phloem and ecosystem function, relatively little research has tried to ex- physiology and plant ecology remains challenging. amine how phloem physiology impacts plant ecology. In this re- Carbon transport occurs in a series of stacked cells, sieve el- view, we highlight several areas of active research where ements, which in angiosperms form long continuous conduits inquiry into phloem physiology has increased our understand- called sieve tubes (for details on cell ultrastructure, see Froelich ing of whole plant function and ecological processes. -

Tree Identification: from Bark and Leaves Or Needles

Tree Identification: from bark and leaves or needles A walk in the woods can be a lot of fun, especially if you bring your kids. How do you get them to come along with you? Tell them this. “Look at the bark on the trees. Can you can find any that look like burnt potato chips, warts, cat scratches, camouflage pants or rippling muscles?” Believe it or not, these are descriptions of different kinds of tree bark. Tree ID from bark:______________________________________________________ Black cherry: The bark looks like burnt potato chips. Hackberry: The bark is bumpy and warty. Ironwood: The bark has long thin strips. With a little imagination, an ironwood can look like it is used as a scratching post by cats. They can also be easily spotted in winter because their light brown dead leaves hang on well past the first snow. Sycamore: A tree with bark that looks like camouflaged pants. The largest tree in Illinois is a sycamore, a majestic 115-foot tree near Springfield. Musclewood: a tree with smooth gray bark covering a trunk with ridges that look like they are rippling muscles. Shagbark hickory: Long strips of shaggy bark peeling at both ends. Cottonwood: Has heavy ridges that make it look like Paul Bunyan’s corduroy pants. Bur oak: Thick and gnarly bark has deep craggy furrows. The corky bark allows it to easily withstand hot forest fires. Tree ID from leaves or needles:________________________________________ Willow Oak: Has elongated leaves similar to those of a willow tree. Red pine: Red has 3 letters; a red pine has groupings of 2-3 prickly needles. -

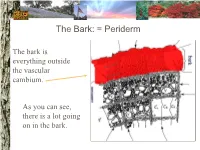

The Bark: = Periderm

The Bark: = Periderm The bark is everything outside the vascular cambium. As you can see, there is a lot going on in the bark. The Bark: periderm: phellogen (cork cambium): The phellogen is the region of cell division that forms the periderm tissues. Phellogen development influences bark appearance. The Bark: periderm: phellem (cork): Phellem replaces the epidermis as the tree increases in girth. Photosynthesis can take place in some trees both through the phellem and in fissures. The Bark: periderm: phelloderm: Phelloderm is active parenchyma tissue. Parenchyma cells can be used for storage, photosynthesis, defense, and even cell division! The Bark: phloem: Phloem tissue makes up the inner bark. However, it is vascular tissue formed from the vascular cambium. The Bark: phloem: sieve tube elements: Sieve tube elements actively transport photosynthates down the stem. Conifers have sieve cells instead. The cambium: The cambium is the primary meristem producing radial growth. It forms the phloem & xylem. The Xylem (wood): The xylem includes everything inside the vascular cambium. The Xylem: a growth increment (ring): The rings seen in many trees represent one growth increment. Growth rings provide the texture seen in wood. The Xylem: vessel elements: Hardwood species have vessel elements in addition to trachieds. Notice their location in the growth rings of this tree The Xylem: fibers: Fibers are cells with heavily lignified walls making them stiff. Many fibers in sapwood are alive at maturity and can be used for storage. The Xylem: axial parenchyma: Axial parenchyma is living tissue! Remember that parenchyma cells can be used for storage and cell division. -

Structural Changes in Senescing Oilseed Rape Leaves at Tissue And

Structural changes in senescing oilseed rape leaves at tissue and subcellular levels monitored by nuclear magnetic resonance relaxometry through water status Maja Musse, Loriane de Franceschi, Mireille Cambert, Clement Sorin, Françoise Le Caherec, Agnès Burel, Alain Bouchereau, Francois Mariette, Laurent Leport To cite this version: Maja Musse, Loriane de Franceschi, Mireille Cambert, Clement Sorin, Françoise Le Caherec, et al.. Structural changes in senescing oilseed rape leaves at tissue and subcellular levels monitored by nuclear magnetic resonance relaxometry through water status. Plant Physiology, American Society of Plant Biologists, 2013, 163 (1), pp.392-406. 10.1104/pp.113.223123. hal-01208634 HAL Id: hal-01208634 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01208634 Submitted on 29 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Structural Changes in Senescing Oilseed Rape Leaves at Tissue and Subcellular Levels Monitored by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Relaxometry through Water Status Maja Musse, Loriane De Franceschi, Mireille Cambert, -

Getting Chemicals Into Trees Without Spraying

Urban Forestry NR/FF/020 (pr) Getting Chemicals Into Trees Without Spraying Michael Kuhns, Forestry Extension Specialist This fact sheet provides an overview of injection, or phellogen that makes cork to thicken the outer bark, implantation, and other ways to get chemicals, mainly phloem that conducts food through the tree from where pesticides, into trees. Many techniques and systems it is stored or made to where it is being used (all of these exist and some are very good, some are good in some tissues together make up the bark), vascular cambium situations, and some are ineffective or bad for trees. that divides rapidly to make new phloem and xylem cells, This fact sheet addresses all of these. and xylem or wood. Xylem includes an outer layer called the sapwood that conducts mostly water and minerals from the roots to the canopy, and an inner layer called the Chemicals are applied to trees for many reasons. heartwood that is aged sapwood that has died and has lost Insecticides repel or kill damaging insects, fungicides its ability to conduct water but still adds strength. treat or prevent fungal diseases, nutrients and plant growth regulators affect growth, and herbicides kill trees or prevent sprouting after tree removal. Spraying is the most typical way to apply these chemicals. It is fast, uses readily available equipment, and is understood. The Phellem (Cork Phellogen down side of spraying is that much of the chemical being or Outer Bark) Phloem applied is wasted, either to drift, run off, or because it can not be applied precisely to where it is needed in the tree. -

Tree Anatomy Stems and Branches

Tree Anatomy Series WSFNR14-13 Nov. 2014 COMPONENTSCOMPONENTS OFOF PERIDERMPERIDERM by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia Around tree roots, stems and branches is a complex tissue. This exterior tissue is the environmental face of a tree open to all sorts of site vulgarities. This most exterior of tissue provides trees with a measure of protection from a dry, oxidative, heat and cold extreme, sunlight drenched, injury ridden site. The exterior of a tree is both an ecological super highway and battle ground – comfort and terror. This exterior is unique in its attributes, development, and regeneration. Generically, this tissue surrounding a tree stem, branch and root is loosely called bark. The tissues of a tree, outside or more exterior to the xylem-containing core, are varied and complexly interwoven in a relatively small space. People tend to see and appreciate the volume and physical structure of tree wood and dismiss the remainder of stem, branch and root. In reality, tree life is focused within these more exterior thin tissue sets. Outside of the cambium are tissues which include transport cells, structural support cells, generation cells, and cells positioned to help, protect, and sustain other cells. All of this life is smeared over the circumference of a predominately dead physical structure. Outer Skin Periderm (jargon and antiquated term = bark) is the most external of tree tissues providing protection, water conservation, insulation, and environmental sensing. Periderm is a protective tissue generated over and beyond live conducting and non-conducting cells of the food transport system (phloem). -

Why Do Animals Eat the Bark and Wood of Trees and Shrubs? William R

FNR-203 Purdue University & Natural Re ry sou Forestry and Natural Resources st rc re e o s F Why Do Animals Eat the Bark and Wood of Trees and Shrubs? William R. Chaney, Professor of Tree Physiology Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 PURDUE UNIVERSITY Animals gnawing the bark and wood of trees anatomy, movement and storage of food in trees, and shrubs is not a malicious act or evidence of a and the variations in digestive systems among neurotic condition. Instead, it is the normal means animals. by which some animals acquire a nutritious food source. The ability to consume this seemingly Constituents of Plant Cell Walls unpalatable food supply and derive nourishment Unlike animals, plants have cells with rigid from it requires specialized feeding habits and cell walls composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, digestive systems. and lignins. Pectins help hold the individual cells together in tissues. All of these substances are potential sources of food for animals. Cellulose The most consummate wood feeders are the A principal component of cell walls is billions of termites throughout the world that cellulose, which consists of 5,000 to 10,000 literally devour thousands of tons of woody glucose molecules joined by a so-called beta debris every year in forests as well as lumber linkage to form straight chain polymers of pure in buildings. Many of our most serious and sugar. The long chains of cellulose are combined damaging insect pests are the bark beetles and first into microfibrils and then further into wood borers that feed on the parts of trees for macrofibrils to create a mesh-like matrix of cell which they are named. -

Shoot Surface Water Uptake Enables Leaf Hydraulic Recovery in Avicennia Marina

Rapid report Rapid report Shoot surface water uptake enables leaf hydraulic recovery in Avicennia marina Tomas I. Fuenzalida1 , Callum J. Bryant1, Leuwin I. Ovington1, Hwan-Jin Yoon2 , Rafael S. Oliveira3 , Lawren Sack4 and Marilyn C. Ball1 1Plant Science Division, Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, Acton, ACT 2601, Australia; 2Statistical Consulting Unit, The Australian National University, Acton, ACT 2601, Australia; 3Department of Plant Biology, Institute of Biology, University of Campinas – UNICAMP, Campinas, S~ao Paulo CP 6109, Brazil; 4Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA Summary Author for correspondence: The significance of shoot surface water uptake (SSWU) has been debated, and it would Tomas I. Fuenzalida depend on the range of conditions under which it occurs. We hypothesized that the decline of Tel: +61 435390065 leaf hydraulic conductance (K ) in response to dehydration may be recovered through Email: [email protected] leaf SSWU, and that the hydraulic conductance to SSWU (Ksurf) declines with dehydration. Received: 16 May 2019 We quantified effects of leaf dehydration on K and effects of SSWU on recovery of K Accepted: 11 August 2019 surf leaf in dehydrated leaves of Avicennia marina. SSWU led to overnight recovery of Kleaf, with recovery retracing the same path as loss of New Phytologist (2019) 224: 1504–1511 Kleaf in response to dehydration. SSWU declined with dehydration. By contrast, Ksurf declined doi: 10.1111/nph.16126 with rehydration time but not with dehydration. Our results showed a role of SSWU in the recovery of leaf hydraulic conductance and Key words: capacitance, drought, foliar revealed that SSWU is sensitive to leaf hydration status. -

Xylem Resin in the Resistance of the Pinaceae to Bark Beetles

XYLEM RESIN IN THE RESISTANCE OF THE PINACEAE TO BARK BEETLES Richard H. Smith Xylem resin-a supersaturation of resin acids in terpenes- appears to play a paradoxical role in the relation of the Pinaceae to tree-killing bark beetles. It has been suggested as the agent responsible for the susceptibility of this coniferous family to beetle attacks. And, at the same time, it has been linked with the ability of the Pinaceae to resist bark beetles. The hosts of tree- killing bark beetles are nearly all Pinaceae-Pinus (pine), Abies (fir), Pseudotsuga (Douglas-fir), Picea (spruce), Tsuga (hemlock), and Larix (larch). Significantly, among conifers, xylem resin is most common and abundant in these Pinaceae. Bark beetles are found on other families of conifers, but they are usually con- sidered of minor importance. Much experimental work has been done since the early reports of an apparent association of resin with resistance. Nearly all studies have dealt with attacking adult beetles; virtually no re- search has been directed at effects of resin on immature forms. Most work has been with Pinus and Dep'roctonus, with lesser attention to spruce, fir, Douglas-fir, and the other genera of bark beetles. PACIFIC This report summarizes the early findings, updates them with results of more recent reports and, in some cases, reinterprets SOUTHWEST these previous reports. This review deals only with bark beetles that attack living trees and with xylem resin, although in a few Forest and Ranee instances, it concerns resin-related chemicals as well. This review follows the approach of Painter (1951), who pro- Experiment station posed that plant resistance to insects depends on one or more FOREST SERVICE U.