Refashioning Sant Tradition in the Eighteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shukteertha Brief Sketch

a brief sketch Shukteerth Shukteerth a brief sketch Swami Omanand Saraswati SWAMI KALYANDEV JI MAHARAJ Shukteerth a brief sketch a brief ,sfrgkfld 'kqdrhFkZ laf{kIr ifjp; ys[kd % Lokeh vksekuUn ljLorh vkbZ ,l ch ,u 978&81&87796&02&2 Website: www.swamikalyandev.com Website: email: [email protected] or [email protected] or [email protected] email: Ph: 01396-228204, 228205, 228540 228205, 01396-228204, Ph: Shri Shukdev Ashram Swami Kalyandev Sewa Trust Shukratal (Shukteerth), Muzaffarnagar, U.P. (India) U.P. Muzaffarnagar, (Shukteerth), Shukratal Trust Sewa Kalyandev Swami Ashram Shukdev Shri Hindi edition of Shukteerth a brief sketch is also available. Please contact us at following address address following at us contact Please available. also is sketch brief a Shukteerth of edition Hindi The Ganges, flowing peacefully by Shuktar, reminds us of the eternal message of ‘tolerance’ for the past five thousand years. Shuktar, described in the Indian mythological scriptures as a place of abstinence, is located on the banks of the holy river, 72 kilometers away from Haridwar. Here, Ganges has, over centuries, cut a swathe through a rocky region to maintain her eternal flow. With the passage of time, Shuktar became famous as Shukratal. Samadhi Mandir of Brahmleen Swami Kalyandev ji Maharaj a brief sketch Shukteerth Shukteerth a brief sketch WRITTEN BY Swami Omanand Saraswati PUBLISHED BY Shri Shukdev Ashram Swami Kalyandev Sewa Trust Shukratal (Shukteerth), Muzaffarnagar, U.P. - 251316 (India) Shukteerth a brief sketch Edited by Ram Jiwan Taparia & Vijay Sharma Designed by Raj Kumar Nandvanshi Published by Vectra Image on behalf of Shri Shukdev Ashram Swami Kalyandev Sewa Trust Shukratal (Shukteerth), Muzaffarnagar, U.P. -

A Review on Historical Earth Pigments Used in India's Wall Paintings

heritage Review A Review on Historical Earth Pigments Used in India’s Wall Paintings Anjali Sharma 1 and Manager Rajdeo Singh 2,* 1 Department of Conservation, National Museum Institute, Janpath, New Delhi 110011, India; [email protected] 2 National Research Laboratory for the Conservation of Cultural Property, Aliganj, Lucknow 226024, India * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Iron-containing earth minerals of various hues were the earliest pigments of the prehistoric artists who dwelled in caves. Being a prominent part of human expression through art, nature- derived pigments have been used in continuum through ages until now. Studies reveal that the primitive artist stored or used his pigments as color cakes made out of skin or reeds. Although records to help understand the technical details of Indian painting in the early periodare scanty, there is a certain amount of material from which some idea may be gained regarding the methods used by the artists to obtain their results. Considering Indian wall paintings, the most widely used earth pigments include red, yellow, and green ochres, making it fairly easy for the modern era scientific conservators and researchers to study them. The present knowledge on material sources given in the literature is limited and deficient as of now, hence the present work attempts to elucidate the range of earth pigments encountered in Indian wall paintings and the scientific studies and characterization by analytical techniques that form the knowledge background on the topic. Studies leadingto well-founded knowledge on pigments can contribute towards the safeguarding of Indian cultural heritage as well as spread awareness among conservators, restorers, and scholars. -

Final Electoral Roll / Voter List (Alphabetical), Election - 2018

THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL / VOTER LIST (ALPHABETICAL), ELECTION - 2018 [As per order dt. 14.12.2017 as well as orders dt.23.08.2017 & 24.11.2017 Passed by Hon'ble Supreme Court of India in Transfer case (Civil) No. 126/2015 Ajayinder Sangwan & Ors. V/s Bar Council of Delhi and BCI Rules.] AT UDAIPUR IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP LOCATION OF POLLING STATION :- BAR ROOM, JUDICIAL COURTS, UDAIPUR DATE 01/01/2018 Page 1 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Electoral Name as on the Roll Electoral Name as on the Roll Number Number ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ ' A ' 77718 SH.AADEP SINGH SETHI 78336 KUM.AARTI TAILOR 67722 SH.AASHISH KUMAWAT 26226 SH.ABDUL ALEEM KHAN 21538 SH.ABDUL HANIF 76527 KUM.ABHA CHOUDHARY 35919 SMT.ABHA SHARMA 45076 SH.ABHAY JAIN 52821 SH.ABHAY KUMAR SHARMA 67363 SH.ABHIMANYU MEGHWAL 68669 SH.ABHIMANYU SHARMA 56756 SH.ABHIMANYU SINGH 68333 SH.ABHIMANYU SINGH CHOUHAN 64349 SH.ABHINAV DWIVEDI 74914 SH.ABHISHEK KOTHARI 67322 SH.ABHISHEK PURI GOSWAMI 45047 SMT.ADITI MENARIA 60704 SH.ADITYA KHANDELWAL 67164 KUM.AISHVARYA PUJARI 77261 KUM.AJAB PARVEEN BOHRA 78721 SH.AJAY ACHARYA 76562 SH.AJAY AMETA 40802 SH.AJAY CHANDRA JAIN 18210 SH.AJAY CHOUBISA 64072 SH.AJAY KUMAR BHANDARI 49120 SH.AJAY KUMAR VYAS 35609 SH.AJAY SINGH HADA 75374 SH.AJAYPAL -

City Development Plan for Udaipur, 2041

City Development Plan for Udaipur, 2041 (Interim City Development Plan) June 2014 Supported under Capacity Building for Urban Development project (CBUD) A Joint Partnership Program between Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India and The World Bank CRISIL Risk and Infrastructure Solutions Limited Ministry of Urban Development Capacity Building for Urban Development Project City Development Plan for Udaipur – 2041 Interim City Development Plan June 2014 Green Lake city of India... Education hub … Hospitality centre…. Abbreviations ADB Asian Development Bank BMTPC Building Materials and Technology Promotion Council BOD Biochemical oxygen demand BPL Below Poverty line BRG Backward Regional Grant BRGF Backward Regional Grant Fund CAA Constitutional Amendment Act CAGR Compound Annual Growth Rate CAZRI Central Arid Zone Research Institute CBUD Capacity Building for Urban Development CCAR Climate Change Agenda for Rajasthan CPCB Central Pollution Control Board CST Central Sales Tax DDMA District Disaster Management Authority DEAS Double entry accounting system DLC District land price committee DPR Detailed Project Report DRR Disaster risk reduction EWS Economically weaker section GDDP Gross District Domestic Product GDP Gross Domestic Product GHG Green House Gases GIS Geo information system HRD Human Resource Development IHSDP Integrated Housing and Slum Development Programme IIM Indian Institute of Management INCCA Indian Network for Climate Change Assessment LOS Level of Services MLD Million Liter per Day NLCP National Lake Conservation -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1779 , 09/01/2017 Class 38

Trade Marks Journal No: 1779 , 09/01/2017 Class 38 2102703 21/02/2011 MR. AMIT V. AGRAWAL trading as ;CAFE CITY C/o. Mr. Agrawal, 2nd Floor, Sagar Arcade, F.C. Road, Pune-411 004. SERVICE PROVIDER INDIAN NATIONAL Address for service in India/Agents address: ANIL DATTARAM SAWANT 2/38 NEW PRADHAN BUILDING ACHARYA DONDE MARG NEAR CHILDREN WADIA HOSPITAL PAREL MUMBAI-400012 Used Since :10/11/2010 MUMBAI COMPUTER SERVICES, NAMELY, PROVIDING ON-LINE FACILITIES FOR REAL-TIME INTERACTION WITH OTHER COMPUTER WITH OTHER COMPUTER USERS CONCERNING TOPICS OF EDUCATION, TELECOMMUNICATIONS, TELECOMMUNICATION OF INFORMATION (INCLUDING WEB PAGES), COMPUTER PROGRAMS AND ANY OTHER DATA; ELECTRONIC MAIL SERVICES; PROVIDING USER ACCESS TO THE INTERNET (SERVICES PROVIDERS); PROVIDING;TELECOMMUNICATIONS CONNECTIONS TO THE INTERNET OR DATABASES; PROVIDING ACCESS TO DIGITAL MUSIC WEB SITES ON THE INTERNET; DELIVERY OF DIGITAL MUSIC BY TELECOMMUNICATIONS; CYBER CAFE, INTERNET CAFE SERVICES, PROVIDING TELECOMMUNICTIONS CONNECTION TO THE INTERNET IN A CAFE ENVIRONMENT, PROVIDING INTERNET CHAT ROOMS, VIDEO GAME PARLOURS, INTERNET GAME PARLOURS. 4537 Trade Marks Journal No: 1779 , 09/01/2017 Class 38 2117580 18/03/2011 ONWARD MOBILITY SOLUTIONS PVT. LTD. D-3136, OBEROI GARDEN, CHANDIVALI, MUMBAI-400072 SERVICES PROVIDER (A REGISTERED INDIAN COMPANY INCORPORATED UNDER INDIAN COMPANIES ACT, 1956 ) Used Since :22/02/2011 MUMBAI TELECOMMUNICATIONS 4538 Trade Marks Journal No: 1779 , 09/01/2017 Class 38 2297811 12/03/2012 ACCESS MATRIX TECHNOLOGIES PVT. LTD, trading as ;ACCESS MATRIX TECHNOLOGIES PVT. LTD, NO. 56, SAI ARCADE, OUTER RING ROAD, DEVARABEESANAHALLI, BANGALORE-560103 TRADE/SERVICES Address for service in India/Agents address: P.V.S. -

Unpaid Dividend-16-17-I3 (PDF)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L72200KA1999PLC025564 Prefill Company/Bank Name MINDTREE LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 17-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 839110.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 49/2 4TH CROSS 5TH BLOCK MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANAND NA KORAMANGALA BANGALORE INDIA Karnataka 560095 72.00 01-May-2024 2539 unpaid dividend KARNATAKA NO 198 ANUGRAHA II FLOOR OLD MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A G SUDHINDRA NA POLICE STATION ROAD INDIA Karnataka 560028 72.00 01-May-2024 2723 unpaid dividend THYAGARAJANAGAR BANGALORE 41 SECRETARIAT COLONY 12038400-00167026- Amount for unclaimed and A JAWAHAR NA INDIA Tamil Nadu 600088 70.00 01-May-2024 ADAMBAKKAM CHENNAI MI00 unpaid dividend -

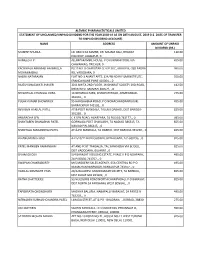

Name Address Amount of Unpaid Dividend (Rs.) Mukesh Shukla Lic Cbo‐3 Ka Samne, Dr

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2018‐19 AS ON 28TH AUGUST, 2019 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 110.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 495.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 KACHWALA ABBASALI HAJIMULLA PLOT NO. 8 CHAROTAR CO OP SOC, GROUP B, OLD PADRA 990.00 MOHMMADALI RD, VADODARA, 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 550.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 412.50 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 SEVANTILAL CHUNILAL VORA 14 NIHARIKA PARK, KHANPUR ROAD, AHMEDABAD‐ 275.00 381001, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 495.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 REVABEN HARILAL PATEL AT & POST MANDALA, TALUKA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐ 825.00 391230, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 495.00 SHANTABEN SHANABHAI PATEL GORWAGA POST CHAKLASHI, TA NADIAD 386315, TA 825.00 NADIAD PIN‐386315, , 0 SHANTILAL MAGANBHAI PATEL AT & PO MANDALA, TA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐391230, , 0 825.00 B HANUMANTH RAO 4‐2‐510/11 BADI CHOWDI, HYDERABAD, A P‐500195, , 0 825.00 PATEL MANIBEN RAMANBHAI AT AND POST TANDALJA, TAL.SANKHEDA VIA BODELI, 825.00 DIST VADODARA, GUJARAT., 0 SIVAM GHOSH 5/4 BARASAT HOUSING ESTATE, PHASE‐II P O NOAPARA, 495.00 24‐PAGS(N) 743707, , 0 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 495.00 -

Cashless Medicliam Policy 2018 Hospital List SNO CARENAME CAREADDRESS CARECITY CARESTATE CAREPIN LOCATION CAREPHONE

Cashless Medicliam Policy 2018 Hospital List SNO CARENAME CAREADDRESS CARECITY CARESTATE CAREPIN LOCATION CAREPHONE 1 ARORA HOSPITAL 42-KRISHNA NAGAR BHARATPUR RAJASTHAN 321001 KRISHNA NAGAR 224667 BHAGWAN MAHAVEER CANCER JAWAHAR LAL NEHRU MARG- 2 HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTRE JAWAHAR LAL NEHRU MARG, NEAR SAARAS SANKUL JAIPUR RAJASTHAN 302004 JAIPUR 2700107/5413104 3 BANSAL HOSPITAL 17, JANAKPURI-FIRST, IMLIPATHAK JAIPUR RAJASTHAN 302005 IMLIPATHAK- JAIPUR 2591110 KOTHARI MEDICAL AND RESEARCH 4 INSTITUTE KOTHARI HOSPITAL MARG, BANGLA NAGAR BIKANER RAJASTHAN 334004 BUNGLA NAGAR 01512210151/ 2210252/ 2210253 5-A-2 VIGYAN NAGAR, AKANSHA OTHOPAEDIC CENTRE, 5 AKANSHA ORTHOPAEDIC CENTRE MAIN ROAD KOTA RAJASTHAN 324002 VIGYAN NAGAR - KOTA 2421369, 2432656 6 JAIN EYE HOSPITAL DAHOD ROAD BANSWARA RAJASTHAN 327001 DAHOD ROAD 254425 7 SHUBH HOSPITAL A-35, VIDYUT NAGAR JAIPUR RAJASTHAN 302021 VIDYUT NAGAR 2245987/ 2351529 8 SAKET HOSPITAL SECTOR 10, MEERA MARG, MANESHWAR JAIPUR RAJASTHAN 302020 MANESHWAR-JAIPUR 01412785074/ 2785075 9 ADITYA HOSPITAL R-5, INDERPURI, LAL KOTHI JAIPUR RAJASTHAN 302015 INDERPURI 01412741459/ 2742466 10 PARDAYA MEMORIAL HOSPITAL SANT KUTIR, MALPANI ROAD, SANGANER JAIPUR RAJASTHAN 302029 SANGANER-JAIPUR 2732914/ 2732915 11 GHIYA HOSPITAL E-68, SIDDARTH NAGAR, MALVIYA NAGAR JAIPUR RAJASTHAN 302017 MALVIYA NAGAR -JAIPUR 1412547279 RAJASTHAN NURSING HOME & EYE 12 CENTRE GOPALPURA, BYPASS JAIPUR RAJASTHAN 302015 GOPALPURA - JAIPUR 0141-2503015/ 2502599 IMPERIAL HOSPITAL & RESEARCH 13 CENTRE KANWATIA CIRCLE, SHASTRI NAGAR JAIPUR -

Deposit Ac List Transfer to Deaf

BARAN NAGRIK SAHAKARI BANK LTD , HEAD OFFICE Unclaim Deposit Account List transfer to Deaf SR.NO NAME ADDRESS 1 MAHAVEER PRASAD BARAN,baran,BARAN-325205 2 RAM BHAROS NAGAR SO KANHEYA LA BARAN,tah mangrol,BARAN-325205 3 PARDEEP KUMAR SHARMA GIRIRAJ BARAN,baran,BARAN-325205 4 HABIB AHAMAD SO IBRAHIM AHAMAD BARAN,TEH KISHANGAJ,BARAN-325205 5 MOHAMMAD SARFARAJ SO ABDUL VAH BARAN,sadar bazar,BARAN-325205 6 DEEN DAYAL NAGAR BARAN,BARAN,BARAN-325205 7 ASHOK KUMAR MEENA BARAN,BARAN,BARAN-325205 8 MOTI LAL BARAN,BANK ROAD BARAN,BARAN-325205 9 BRILIANT EDUCATIONAL AND WELFA BARAN,colony,BARAN-325205 10 JAHID HUSAIN SO KAMRUDDIN BARAN,anta,BARAN-325205 11 DURGA LAL NAGAR SO DHULI LAL BARAN,TEL FECTORY,BARAN-325205 12 CHANDRA SHEKHAR KELASH BARAN,CHOMUKHA BAZAR,BARAN-325205 GRAM POST HANOTIYA,PATHERA TH-BARAN,BARAN,BARAN- HEMRAJ SO NENAGI RAM 13 325205 14 ASHOK KUMAR SO RAM KALYAN BARAN,BARAN,BARAN-325205 15 SEEMA KUMARI MEENA BARAN,BARAN,BARAN-325205 16 PRAHLAD SINGH BARAN,GODIA MEHAR,BARAN,BARAN-325205 17 SANGITA KUMARI DO SHANTI LAL BARAN,BARAN,BARAN-325205 18 PAVAN SAPRA SO RADHRSHYAM SAPR BARAN,INDRA MARKET,BARAN-325205 19 TEJ KARAN NAMA SO BAJRANG LAL BARAN,BARAN,BARAN-325205 20 SATYANARAYAN BANSAL SO PREM CH BARAN,TAH ATRU,BARAN-325205 21 LILADHAR MEENA SO NENGI RAM BARAN,POST TULSA,BARAN-325205 22 MAHAVIR PRASAD SUMAN BARAN,ATRU BARAN,BARAN-325205 23 DWARAKI LAL MEENA SO NENKEE LA BARAN,TAH KISHANGAJ,BARAN-325205 24 KANHAIYA LAL SHREE LAL BARAN,TEH ATRU,BARAN-325205 25 SURAJ KARA MEGHWAL SO AMAR LAL BARAN,post kalmanda,BARAN-325205 26 MAHENDAR -

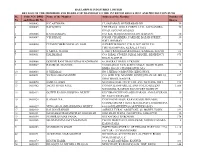

SL No. Folio NO./ DPID and Client ID No. Name of the Member Address of the Member Number of Shares 1 0000002 H C ASTHANA 17

BALLARPUR INDUSTRIES LIMITED DETAILS OF THE MEMBERS AND SHARE FOR TRANSFER TO THE INVESTOR EDUCATION AND PROTECTION FUND SL Folio NO./ DPID Name of the Member Address of the Member Number of No. and Client ID No. Shares 1 0000002 H C ASTHANA 17, SAIFABAD, HYDERABAD-DN. 30 2 0000003 RAFIQ BEG THE PRAGA TOOLS CORPN. LTD., ALEXANDRA 30 ROAD, SECUNDARABAD. 3 0000006 K M HAMEEDA C/O. K.B. MAQSOOD HUSSAIN, BADAUN, 30 4 0000007 V K DHAGE PODAR CHAMBERS, PARESEE BAZAR STREET, 30 FORT, BOMBAY 5 0000020 PUTHENCHERI GOPALAN NAIR SUPERINTENDENT, P.W.D. M.P. RETD P.O. 75 TIRUVEGAPPURA, KERALA STATE 6 0000029 S ABDUL WAHIB 5, OLD TRANQUEBAR STREET, KARIKAL, SOUTH 63 7 0000051 HALIMABAI C/O. IQBAL STORES, IQBAL MANZIL, RESIDENCY 975 ROAD, NAGPUR. 8 0000066 GOBIND RAM THAKURDAS WADHWANI 48, HAZRAT GANJ LUCKNOW. 3 9 0000067 RAMBHAU BANGDE C/O BHARATI SAW & RICE MILLS, EKORI WARD, 72 BINBA ROAD, CHANDRAPUR, M.S. 10 0000083 S J KHARAS NO.5,JEERA COMPOUND, KINGSWAY, 9 11 0000091 VATSALABAI MANDPE C/O. SHRI D.W. MANDPE, HINDUSTHAN OIL MILLS, 657 GHAT ROAD, NAGPUR. 12 0000098 SAMUEL JOHN NETURIA COAL CO./P/ LTD., P.O. NETURIA, DIST. 192 13 0000102 JAGJIT SINGH PAUL C/O.M/S. BANWARILAL AND CO LTD QUEENS 1,566 MANSIONS, BASTION ROAD FORT BOMBAY 14 0000122 GOTETI RADHA KRISHNA MURTY KUCHMANCHIVANI AGRAHARAM, AMALAPURAM, 30 DT. EAST GODAVARI. 15 0000124 K ANASUYA C/O P PATHU RAJU KEAVEKALKURGUMME 3 GUDDE,CIRCAR THOTA MACHLIPATTAM,KRISHNA 16 0000127 VENGARA RADHAKRISHNA MURTY 4-61/10 DILSHUKHNAGAR HYDERABAD 78 17 0000129 BALWANT SINGH AGRICULTURAL ASSISTANT, 85, MODEL TOWN, 192 18 0000131 GANGABAI MAHADEORAO JOGLEKAR JOGLEKAR WADA, GANJIPURA, JABALPUR. -

Hdfc Pfm 2531195 15/05/2013 Hdfc Pension Management Company Ltd

Trade Marks Journal No: 1947 , 11/05/2020 Class 36 HDFC PFM 2531195 15/05/2013 HDFC PENSION MANAGEMENT COMPANY LTD. 13TH FLOOR, LODHA EXCELUS, APOLLO MILLS COMPOUND, N.M. JOSHI MARG, MAHALAXMI, MUMBAI-400011 SERVICE PROVIDER A COMPANY INCORPORATED UNDER THE COMPANIES ACT, 1956 Address for service in India/Agents address: WADIA GHANDY & CO. N.M. WADIA BUILDING,123, MAHATMA GANDHI ROAD, MUMBAI - 400 001. Used Since :01/04/2013 MUMBAI PENSION FUND MANAGEMENT AND RELATED FINANCIAL AND MONETARY SERVICES 3664 Trade Marks Journal No: 1947 , 11/05/2020 Class 36 2982045 09/06/2015 ROBINHOOD INSURANCE BROKER PVT. LTD. trading as ;Robinhood Insurance Broker Pvt. Ltd. E-131, Kailash Industrial Complex, Near Hiranandani Powai, Vikhroli (W), Mumbai 400079 SERVICE PROVIDER Body Incorporate Address for service in India/Attorney address: VISHAL JAIN 2B, Ramdwara Colony, Mahaveer Nagar, Near Durgapura Railway Station, Jaipur-302018 Used Since :06/06/2015 To be associated with: 2796887 MUMBAI ACTUARIAL SERVICES, REAL ESTATE EVALUATION, INSURANCE EVALUATION, FINANCIAL EVALUATION, INSURANCE BROKERAGE, INSURANCE CONSULTANCY, INSURANCE INFORMATION AND INSURANCE UNDERWRITING FOR ACCIDENT, FIRE, HEALTH AND MARINE. THIS IS SUBJECT TO ASSOCIATION WITH REGISTERED/PENDING REGISTRATION NO..2796887. 3665 Trade Marks Journal No: 1947 , 11/05/2020 Class 36 3092147 02/11/2015 PRASUN KUMAR PANKAJ 112 K / 25 A, BHOLA KA PURA, PRITAM NAGAR, ALLAHABAD, UTTAR PRADESH SERVICE PROVIDER Address for service in India/Attorney address: NAVDEEP SHRIDHAR 111, Chandralok Complex, Birhana Road, Kanpur, 208001, U.P. Used Since :06/10/1988 DELHI FINANCIAL AFFAIRS, MONETARY AFFAIRS, REAL ESTATE AFFAIRS 3666 Trade Marks Journal No: 1947 , 11/05/2020 Class 36 3393436 20/10/2016 MITRA INFRA LIMITED trading as ;REAL ESTATE BUSINESS A/347, SITUATED AT BUDHA MARG MAIN ROAD MANDAWALI NEW DELHI-110092 REAL ESTATE BUSINESS Address for service in India/Attorney address: MEENU VERMA J-178 B VISHNU GARDEN, NEAR SHAKTI MANDIR, NEW DELHI-110018. -

Kiosk Name Kiosk District Phone No Address Dinesh

KIOSK_NAME KIOSK_DISTRICT PHONE_NO ADDRESS DINESH BARFA Jodhpur 9667425356 RAJIV GHANDHI NIRMAN BHAEAN PDASHLAKALA BILARA JODHPUR Gunesh Ram Jodhpur 9521508520 TANDIO KI DHANI V/P-SALWA KALAN TH.JODHPUR DIS. JODHPUR Hari Ram Jodhpur 9782094486 Aatal Seva Center,DangiyawasJodhpurPin Code- 342027 Jagdish Jodhpur 9950120514 SHREE BALAJI E-MITRA, Vill. Modi Joshiyan Gram Panchayat. Modi Joshiyan, Block. Luni Dist. Jodhpur(342027) Jala Ram Jodhpur 9602169984 V/P Agolai, Th. Balesar Dist Jodhpur Jitendra Jodhpur 9252065933 JAJIVAL KALLA,VAYA BANARJODHPUR,PIN-342027undefined Narendra Singh Jodhpur 2920264413 Vill. Khareiya KhangarG/P Khariya Khangarblock Bhopalgarh Jodhpur Pankaj Gehlot Jodhpur 8952921539 Main Market,Kali BeriJodhpur A K COMPUTER POINT Jodhpur 9928144326 k.k. market jodhpur road pipar city A K Computer Point Jodhpur 9928144326 K K Market New Bus Stand Jodhpur Road Pipar City AAICHUKI DEVI Jodhpur 9001159228 KISHANPURA, DHADHIYA LUNI JODHPUR RAJASTHAN AAMEEN KHAN Jodhpur 9166750753 MALAR ROAD PHALODI ABDUL RASHEED Jodhpur 9785528235 OLD CINEMA HALL, NEAR VIJAY CIRCLE, PIPAR CITY JODHPUR ABDUL RAZZAK Jodhpur 9950010896 H.NO. 649, TULASI COLONY KABIR NAGAR, JODHPUR RAJASTHANundefined ABHISHEK Jodhpur 9166417884 201,LAXMI NAGAR PAOTA C ROAD JODHPUR ABHISHEK PHOPHALIYA Jodhpur 9610011006 COURT KE SAMENE station road phalodi ADITYA CHANDAK Jodhpur 9829605108 TEHSIL ROAD NEAR SBI BANK,OSIAN, JODHPUR AJAJ AHMAD Jodhpur 8003786948 OLD BUS STAND ASOP BHOPALGARH JODHPUR AJAY JAIN Jodhpur 9414077155 1 - C RoadSardarpuraDisst. - Jodhpur AJAY