Revisiting Joseph Smith and the Availability of the Book of Enoch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

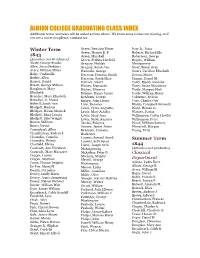

ALBION COLLEGE GRADUATING CLASS INDEX Additional Terms and Years Will Be Added As Time Allows

ALBION COLLEGE GRADUATING CLASS INDEX Additional terms and years will be added as time allows. We know some names are missing, so if you see a correction please, contact us. Winter Term Green, Denslow Elmer Pray Jr., Isaac Green, Harriet E. F. Roberts, Richard Ely 1843 Green, Marshall Robertson, George [Attendees not Graduates] Green, Perkins Hatfield Rogers, William Alcott, George Brooks Gregory, Huldah Montgomery Allen, Amos Stebbins Gregory, Sarah Ann Stout, Byron Gray Avery, William Miller Hannahs, George Stuart, Caroline Elizabeth Baley, Cinderella Harroun, Denison Smith Sutton, Moses Barker, Ellen Harroun, Sarah Eliza Timms, Daniel M. Barney, Daniel Herrick, Albert Torry, Ripley Alcander Basset, George Stillson Hickey, Manasseh Torry, Susan Woodbury Baughman, Mary Hickey, Minerva Tuttle, Marquis Hull Elizabeth Holmes, Henry James Tuttle, William Henry Benedict, Mary Elizabeth Ketchum, George Volentine, Nelson Benedict, Jr, Moses Knapp, John Henry Vose, Charles Otis Bidwell, Sarah Ann Lake, Dessoles Waldo, Campbell Griswold Blodgett, Hudson Lewis, Cyrus Augustus Ward, Heman G. Blodgett, Hiram Merrick Lewis, Mary Athalia Warner, Darius Blodgett, Mary Louisa Lewis, Mary Jane Williamson, Calvin Hawley Blodgett, Silas Wright Lewis, Sarah Augusta Williamson, Peter Brown, William Jacobs, Rebecca Wood, William Somers Burns, David Joomis, James Joline Woodruff, Morgan Carmichael, Allen Ketchum, Cornelia Young, Urial Chamberlain, Roderick Rochester Champlin, Cornelia Loomis, Samuel Sured Summer Term Champlin, Nelson Loomis, Seth Sured Chatfield, Elvina Lucas, Joseph Orin 1844 Coonradt, Ann Elizabeth Mahaigeosing [Attendees not graduates] Coonradt, Mary Margaret McArthur, Peter D. Classical Cragan, Louisa Mechem, Stanley Cragan, Matthew Merrill, George Department Crane, Horace Delphin Washington Adkins, Lydia Flora De Puy, Maria H. Messer, Lydia Allcott, George B. -

Og King of Bashan, Enoch and the Books of Enoch: Extra-Canonical Texts and Interpretations of Genesis 6:1–4’* Ariel Hessayon

Chapter 1 ‘Og King of Bashan, Enoch and the Books of Enoch: Extra-Canonical Texts and Interpretations of Genesis 6:1–4’* Ariel Hessayon It is not the Writer, but the authority of the Church, that maketh a Book Canonical [Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (1651), part III, chap. 33 p. 204] For only Og king of Bashan remained of the remnant of the giants (Deuteronomy 3:11) Renaissance Humanist, Franciscan friar, Benedictine monk, Doctor of Medicine and ‘Great Jester of France’, François Rabelais (c.1490–1553?) was the author of La vie, faits & dits Heroiques de Gargantua, & de son filz Pantagruel (Lyon, 1564). A satirical masterpiece with liberal dollops of scatological humour, it tells the irreverent story of Gargantua, his son Pantagruel and their companion Panurge. Gargantua and Pantagruel are giants and in an allusion to the Matthean genealogy of Christ the first book begins with a promised account of how ‘the Giants were born in this world, and how from them by a direct line issued Gargantua’. Similarly, the second book introduces a parody of the Old Testament genealogies: And the first was Chalbroth who begat Sarabroth who begat Faribroth who begat Hurtali, that was a brave eater of pottage, and reigned in the time of the flood. Acknowledging readers would doubt the veracity of this lineage, ‘seeing at the time of the flood all the world was destroyed, except Noah, and seven persons more with him in the Ark’, Rabelais described how the giant Hurtali survived the deluge. Citing the authority of a rabbinic school known as the Massoretes, ‘good honest fellows, true ballokeering blades, and exact Hebraical bagpipers’, Rabelais explained that Hurtali did not get in the ark (he was too big), but rather sat astride upon it, with ‘one leg on the one side, and another on the other, as little children use to do upon their wooden 6 Scripture and Scholarship in Early Modern England horses’. -

The Response to Joseph Smith's Innovations in the Second

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2011 Recreating Religion: The Response to Joseph Smith’s Innovations in the Second Prophetic Generation of Mormonism Christopher James Blythe Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Blythe, Christopher James, "Recreating Religion: The Response to Joseph Smith’s Innovations in the Second Prophetic Generation of Mormonism" (2011). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 916. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/916 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECREATING RELIGION: THE RESPONSE TO JOSEPH SMITH’S INNOVATIONS IN THE SECOND PROPHETIC GENERATION OF MORMONISM by Christopher James Blythe A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: _________________________ _________________________ Philip L. Barlow, ThD Daniel J. McInerney, PhD Major Professor Committee Member _________________________ _________________________ Richard Sherlock, PhD Byron R. Burnham, EdD Committee Member Dean of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2010 ii Copyright © Christopher James Blythe 2010 All rights reserved. iii ABSTRACT Recreating Religion: The Response to Joseph Smith’s Innovations in the Second Prophetic Generation of Mormonism by Christopher James Blythe, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2010 Major Professor: Philip Barlow Department: History On June 27, 1844, Joseph Smith, the founder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was assassinated. -

List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007 A - J Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 A complete listing of all Fellows and Foreign Members since the foundation of the Society A - J July 2007 List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 The list contains the name, dates of birth and death (where known), membership type and date of election for all Fellows of the Royal Society since 1660, including the most recently elected Fellows (details correct at July 2007) and provides a quick reference to around 8,000 Fellows. It is produced from the Sackler Archive Resource, a biographical database of Fellows of the Royal Society since its foundation in 1660. Generously funded by Dr Raymond R Sackler, Hon KBE, and Mrs Beverly Sackler, the Resource offers access to information on all Fellows of the Royal Society since the seventeenth century, from key characters in the evolution of science to fascinating lesser- known figures. In addition to the information presented in this list, records include details of a Fellow’s education, career, participation in the Royal Society and membership of other societies. Citations and proposers have been transcribed from election certificates and added to the online archive catalogue and digital images of the certificates have been attached to the catalogue records. This list is also available in electronic form via the Library pages of the Royal Society web site: www.royalsoc.ac.uk/library Contributions of biographical details on any Fellow would be most welcome. -

1781 – Core – 17 the Book of Common Prayer and Administration

1781 – Core – 17 The book of common prayer and administration of the Sacraments ... according to the use of the Church of England: together with the Psalter or Psalms of David.-- 12mo.-- Oxford: printed at the Clarendon Press, By W. Jackson and A. Hamilton: and sold at the Oxford Bible Warehouse, London, 1781 Held by: Glasgow The Book of Common Prayer, etc. / LITURGIES.-- 32o..-- Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1781. Held by: British Library Church of England. The book of common prayer, and administration of the sacraments, ... together with the Psalter ... Oxford : printed at the Clarendon Press, by W. Jackson and A. Hamilton: sold by W. Dawson, London, 1781. 8°.[ESTC] Collectanea curiosa; or Miscellaneous tracts : relating to the history and antiquities of England and Ireland, the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, and a variety of other subjects / Chiefly collected, and now first published, from the manuscripts of Archbishop Sancroft; given to the Bodleian Library by the late bishop Tanner. In two volumes.-- 2v. ; 80.-- Oxford : At the Clarendon Press, printed for the editor. Sold by J. and J. Fletcher, and D. Prince and J. Cooke, in Oxford. And by J. F. and C. Rivington, T. Cadell, and J. Robson, in London; and T. Merrill, in Cambridge., MDCCLXXXI Notes: Corrections vol. 2 p. [xii].-- Dedication signed: John Gutch .-- For additional holdings, please see N66490 .-- Index to both vol. in vol. 2 .-- Microfilm, Woodbridge, CT, Research Publications, Inc., 1986, 1 reel ; 35mm, (The Eighteenth Century ; reel 6945, no.02 ) .-- Signatures: vol. 1: pi2 a-e4 f2 a-b4 c2 A-3I4; vol. 2: pi2(-pi2) a4 b2 A-3M4 3N2 .-- Vol. -

The Descendants of John Pease 1

The Descendants of John Pease 1 John Pease John married someone. He had three children: Edward, Richard and John. Edward Pease, son of John Pease, was born in 1515. Basic notes: He lived at Great Stambridge, Essex. From the records of Great Stambridge. 1494/5 Essex Record office, Biography Pease. The Pease Family, Essex, York, Durham, 10 Henry VII - 35 Victoria. 1872. Joseph Forbe and Charles Pease. John Pease. Defendant in a plea touching lands in the County of Essex 10 Henry VII, 1494/5. Issue:- Edward Pease of Fishlake, Yorkshire. Richard Pease of Mash, Stanbridge Essex. John Pease married Juliana, seized of divers lands etc. Essex. Temp Henry VIII & Elizabeth. He lived at Fishlake, Yorkshire. Edward married someone. He had six children: William, Thomas, Richard, Robert, George and Arthur. William Pease was born in 1530 in Fishlake, Yorkshire and died on 10 Mar 1597 in Fishlake, Yorkshire. William married Margaret in 1561. Margaret was buried on 25 Oct 1565 in Fishlake, Yorkshire. They had two children: Sibilla and William. Sibilla Pease was born on 4 Sep 1562 in Fishlake, Yorkshire. Basic notes: She was baptised on 12 Oct 1562. Sibilla married Edward Eccles. William Pease was buried on 25 Apr 1586. Basic notes: He was baptised on 29 May 1565. William next married Alicia Clyff on 25 Nov 1565 in Fishlake, Yorkshire. Alicia was buried on 19 May 1601. They had one daughter: Maria. Maria Pease Thomas Pease Richard Pease Richard married Elizabeth Pearson. Robert Pease George Pease George married Susanna ?. They had six children: Robert, Nicholas, Elizabeth, Alicia, Francis and Thomas. -

Church of Ireland), Dublin, Ireland from Public Garden on the North Side of the Cathedral

Figure 1. St Patrick's Cathedral (Church of Ireland), Dublin, Ireland from public garden on the north side of the Cathedral https://c2.staticflickr.com/6/5586/14969137398_f4622a9ab9_z.jpg Figure 2. The Lady Chapel as restored in 2012-13. For 150 years, this was the site of L'Église Française de St Patrick. http://www.docbrown.info/docspics/irishscenes/Ireland2016/Dsc_1496.jpg Huguenot Settlement of Ireland St. Patrick’s (Church of Ireland) Cathedral and the Lady Chapel or L’Église Française On Saint Patrick’s Day, March 17, 2017, I wrote the first on three notes on the Huguenot settlement in Ireland. I thought that there was enough information of value in the three notes that they should be revised into an essay St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Church of Ireland) was founded during the Norman Conquest of Ireland most probably on a much older Celtic church. In 1191, Anglo-Norman John Comyn (c.1150- 1212) Archbishop of Dublin, made a parish church dedicated to St. Patrick the site of the Archbishop’s seat for Dublin. The old parish church was torn down and a much larger Norman (Romanesque) stone church was started. Construction was completed enough that Comyn dedicated the church to God, the blessed Lady Mary and Saint Patrick on 17 March 1191/2. [Since the Old Style calendar was in use, the new year did not begin until March 25.] At the time, the church was outside the boundaries of the town of Dublin. Within the boundaries of Dublin, there was a cathedral already, Christ Church Cathedral founded about 1030. -

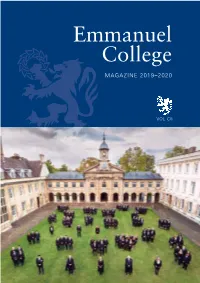

View 2020 Edition Online

Emmanuel Emmanuel College College MAGAZINE 2019–2020 VOL CII MAGAZINE 2019–2020 VOLUME CII Emmanuel College St Andrew’s Street Cambridge CB2 3AP Telephone +44 (0)1223 334200 THE YEAR IN REVIEW I Emmanuel College MAGAZINE 2019–2020 VOLUME CII II EMMANUEL COLLEGE MAGAZINE 2019–2020 The Magazine is published annually, each issue recording college activities during the preceding academical year. It is circulated to all members of the college, past and present. Copy for the next issue should be sent to the Editors before 30 June 2021. Enquiries, news about members of Emmanuel or changes of address should be emailed to [email protected], or submitted via the ‘Keeping in Touch’ form: https://www.emma.cam.ac.uk/keepintouch/. General correspondence about the Magazine should be addressed to the General Editor, College Magazine, Dr Lawrence Klein, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. The Obituaries Editor (The Dean, The Revd Jeremy Caddick), Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP is the person to contact about obituaries. The college telephone number is 01223 334200, and the email address is [email protected]. If possible, photographs to accompany obituaries and other contributions should be high-resolution scans or original photos in jpeg format. The Editors would like to express their thanks to the many people who have contributed to this issue, and especially to Carey Pleasance for assistance with obituaries and to Amanda Goode, the college archivist, whose knowledge and energy make an outstanding contribution. Back issues The college holds an extensive stock of back numbers of the Magazine. Requests for copies of these should be addressed to the Development Office, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. -

MULTIPURPOSE TOOLS for BIBLE STUDY Revised and Expanded Edition to the Best Commentary on Proverbs 31:10-31 Copyright O 1993 Augsburg Fortress

F REDERICK W. D ANKER M ULTIPURPOSE TOOLS FOR B IBLE STUDY REVISED AND EXPANDED EDITION FORTRESS PRESS MINNEAPOLIS MULTIPURPOSE TOOLS FOR BIBLE STUDY Revised and Expanded Edition To the best commentary on Proverbs 31:10-31 Copyright o 1993 Augsburg Fortress. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher. Write to: Permissions, Augsburg Fortress, 426 S. Fifth St., Box 1209, Minneapolis, MN 55440. Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright Q 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used with permission. Interior design: The HK Scriptorium, Inc. Cover design: McCormick Creative Cover photo: Cheryl Walsh Bellville Special thanks to Luther Northwestern Theological Seminary, St. Paul, Minnesota, and curator Terrance L. Dinovo, for use of its Rare Books Room in the cover photography. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Danker, Frederick W. Multipurpose tools for Bible study / Frederick W. Danker. - Rev. and expanded ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN o-8006-2598-6 (alk. paper) 1. Bible-Criticism, interpretation, etc. 2. Bible-Bibliography. I. Title. BSSll.Z.D355 1993 220’.07-dc20 93-14303 CID The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 2329.49-1984. @ Manufactured in the U.S.A. AF 1-2598 97 96 95 94 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 IO CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS vii PREFACE xi 1. -

In God's Image and Likeness 2: Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel

In God’s Image and Likeness 2 Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel Excursus, Bibliography, References & Indexes Authors: Jeffrey M. Bradshaw and David J. Larsen This book from which this chapter is excerpted is available through Eborn Books: https://ebornbooks.com/shop/non-fiction/mormon-lds/mormon-new/in-gods-image- likeness-2-enoch-noah-tower-of-babel/ Recommended Citation Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. In God's Image and Likeness 2, Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, https://interpreterfoundation.org/reprints/in-gods-image-and-likeness-2/IGIL2IChap09.pdf. Front Matter – iii In God’s Image and Likeness 2 Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel Jeffrey M. Bradshaw David J. Larsen TempleThemes.net The Interpreter Foundation Eborn Books 2014 iv Front Matter – © 2014 Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, http://www.templethemes.net All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any format or in any medium without written permission from the first author, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. Unauthorized public performance, broadcasting, transmission, copying, mechanical or electronic, is a violation of applicable laws. This product and the individual images contained within are protected under the laws of the United States and other countries. Unauthorized duplication, distribution, transmission, or exhibition of the whole or of any part therein may result in civil liability and criminal prosecution. The downloading of images is not permitted. This work is not an official publication of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The views that are expressed within this work are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or any other entity. -

%Iitsijir2 Berurbs Éurietp (Formerly the Records Branch of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society)

%iItsIJir2 Berurbs éurietp (formerly the Records Branch of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society) VOLUME XXV FOR THE YEAR 1969 Impression of 400 copies ABSTRACTS OF WILTSHIRE INCLOSURE AWARDS AND AGREEMENTS EDITED BY R. E. SANDELL DEVIZES 1971 © Wiltshire Record Society (formerly Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Records Branch), 1971 SBN: 901333 02 6 Set in Times New Roman 10/ll pt. PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY THE GLEVUM PRESS LTD., GLOUCESTER CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE . xi ABBREVIATIONS xii INTRODUCTION . Historical and Legislative Background The Documents . Inclosure by Parliamentary Award in Wiltshire Commissioners, Surveyors, and Mapmakers Arrangement of the Abstracts . 0'0—-..lUI-b'-* ABSTRACTS o1= WILTSHIRE INCLOSURE AWARDS AND AGREEMENTS 1. Aldbourne . 11 2. Alderbury . 12 3. Alderbury (Pitton and Farley) I3 4. Allington .. .. .. 13 5. Alvediston . 14 6. Ashton Keynes (Leigh) 14 7. Ashton Keynes . 15 8. Steeple Ashton . 16 9. Avebury . 13 l0. Barford St. Martin .. .. l9 ll. Great Bedwyn (Crofton Fields) 20 12. Great Bedwyn .. .. .. 20 13. Great Bedwyn (Marten) . 22 14. Little Bedwyn . 22 15. Berwick St. James 23 l6. Berwick St. John . 23 17. Berwick St. Leonard . 24 18. Biddestone . 25 19. Bishopstone (North Wilts.) 25 20. Bishopstone (South Wilts.) 26 21. Bishopstrow .. .. 27 22. Boscombe . 28 23. Boyton . 28 V CONTENTS PAGE Bradford on Avon (Trowle Common). 28 Bradford on Avon (Holt) . 29 Bradford on Avon (Bradford Leigh Common, Forwards Common) .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 29 North Bradley and Southwick . 29 Bremhill . 31 Brinkworth 31 Britford . 32 Bromham.. .. .. .. .. .. 32 Burbage, Collingbourne Kingston, and Poulton 33 Calne . 34 All Cannings . 36 Bishop's Cannings (Coate) . 37 Bishop’s Cannings, Chittoe, and Marden . -

Joseph Smith, Mormonism and Enochic Tradition

Durham E-Theses Joseph Smith, Mormonism and Enochic Tradition CIRILLO, SALVATORE How to cite: CIRILLO, SALVATORE (2010) Joseph Smith, Mormonism and Enochic Tradition, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/236/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 1 Salvatore Cirillo Research MA Durham University Department of Theology September 30, 2009 Joseph Smith, Mormonism and Enochic Tradition This thesis is a result of my own work. Material from the work of others has been acknowledged and quotations and paraphrases suitably indicated. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published in any format, including electronic and the Internet, without the author‘s prior written consent. All information derived from this thesis must be acknowledged appropriately. 2 3 CONTENTS CONTENTS .................................................................................................................. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .........................................................................................