The Newsman's Privilege: an Empirical Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POLETTA LOUIS ’92 Martin Luther King Jr

ReflectionsA PUBLICATION OF THE SUNY ONEONTA ALUMNI ASSOCIATION SPRING 2020 POLETTA LOUIS ’92 Martin Luther King Jr. Day Keynote Speaker ALSO... Earth & Atmospheric Sciences and School of Economics & Business celebrate 50 Years ReflectionsVolume XLXIII Number 3 Spring 2020 FROM NETZER 301 RECENT DONATION 2 20 TO ALDEN ROOM FROM THE ALUMNI @REDDRAGONSPORTS 3 ASSOCIATION 23 COLLEGE FOUNDATION 4 ACROSS THE QUAD 25 UPDATES EARTH & ATMOSPHERIC SCIENCES 2020 ALUMNI AWARD 11 50TH ANNIVERSARY 27 WINNERS 14 MARK YOUR CALENDAR 15 ALUMNI IN BARCELONA SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS & BUSINESS BEYOND THE PILLARS 15 50TH ANNIVERSARY 30 BEHIND THE DOOR: A LOOK ALUMNI PROFILE: 18 AT EMILY PHELPS’ OFFICE 41 ROZ HEWSENIAN ’75 On the Cover: Poletta Louis ’92 connects Martin Luther King Jr.’s civil rights legacy to the continuing struggle for equality and justice in all facets of our society. Photo by Gerry Raymonda Reflections Vol. XLXIII Number 3 Spring 2020 MANAGING EDITOR Laura M. Lincoln EDITOR Adrienne Martini LEAD DESIGNER Jonah Roberts CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Adrienne Martini Geoffrey Hassard Benjamin Wendrow ’08 CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Gerry Raymonda Michael Forster Rothbart Reflections is published three times a year by the Division of College Advancement and is funded in part by the SUNY Oneonta Alumni Association through charitable gifts to the Fund for Oneonta. SUNY Oneonta Oneonta, NY 13820-4015 Postage paid at Oneonta, NY POSTMASTER Address service requested to: Reflections Office of Alumni Engagement Ravine Parkway Reconnect SUNY Oneonta Oneonta, NY 13820-4015 Follow the Alumni Association for news, events, contests, photos, and more. For links to all of our Reflections is printed social media sites, visit www.oneontaalumni.com on recylced paper. -

C3972 Wilson, Theo, Papers, 1914-1997 Page 2 Such Major Trials As the Pentagon Papers, Angela Davis, and Patty Hearst

C Wilson, Theo R. (1917-1997), Papers, 1914-1997 3972 9 linear feet, 2 linear feet on 4 rolls of microfilm, 1 video cassette, 1 audio cassette, 1 audio tape MICROFILM (Volumes only) This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. INTRODUCTION The papers of Theodore R. Wilson, trial reporter for the New York Daily News, consist of newspaper articles, trial notes, awards, correspondence, photographs, and miscellaneous items spanning her 60-year career as a reporter and writer. DONOR INFORMATION The Theo Wilson Papers were donated to the University of Missouri by her son, Delph R. Wilson, on 5 August 1997 (Accession No. 5734). Additional items were donated by Linda Deutsch during August 1999 (Accession No. 5816). The Wilson papers are part of the National Women and Media Collection. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Theodora Nadelstein, the youngest of 11 children, was born in Brooklyn, New York, on 22 May 1917. She was first published at age eight in a national magazine for her story on the family’s pet monkey. Subsequent poems, short stories, plays, and articles of hers were published and produced at Girls High School in Brooklyn, which she attended from 1930 to 1934. She enrolled at the University of Kentucky where she became a columnist and associate editor of the school newspaper, the Kentucky Kernel, despite never taking any journalism courses. She graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1937 at age 19 and immediately went to work at the Evansville Press in Indiana. At the Press she was quickly promoted to tri-state editor, writing and handling copy from Indiana, Kentucky, and Illinois. -

House Section

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JUNE 21, 2005 No. 83 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was I would like to read an e-mail that there has never been a worse time for called to order by the Speaker pro tem- one of my staffers received at the end Congress to be part of a campaign pore (Miss MCMORRIS). of last week from a friend of hers cur- against public broadcasting. We formed f rently serving in Iraq. The soldier says: the Public Broadcasting Caucus 5 years ‘‘I know there are growing doubts, ago here on Capitol Hill to help pro- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO questions and concerns by many re- mote the exchange of ideas sur- TEMPORE garding our presence here and how long rounding public broadcasting, to help The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- we should stay. For what it is worth, equip staff and Members of Congress to fore the House the following commu- the attachment hopefully tells you deal with the issues that surround that nication from the Speaker: why we are trying to make a positive important service. difference in this country’s future.’’ There are complexities in areas of le- WASHINGTON, DC, This is the attachment, Madam June 21, 2005. gitimate disagreement and technical I hereby appoint the Honorable CATHY Speaker, and a picture truly is worth matters, make no mistake about it, MCMORRIS to act as Speaker pro tempore on 1,000 words. -

Ex-Spouse Arrested in Killing of Woman

IN SPORTS: Crestwood’s Blanding to play in North-South All-Star game B1 LOCAL Group shows its appreciation to Shaw airmen TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 21, 2017 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 75 cents A5 Ex-spouse Community enjoys Thanksgiving meal arrested after volunteers overcome obstacles in killing of woman Victim was reported missing hours before she was discovered in woods BY ADRIENNE SARVIS [email protected] The ex-husband of the 27-year- old woman whose body was found in a shallow grave in Manchester State Forest last week has been charged in her death. James Ginther, 26, of Beltline J. GINTHER Boulevard in Columbia, was ar- rested on Monday in Louisville, Kentucky, for allegedly kidnapping and killing Suzette Ginther. Suzette’s body was found in the state forest about 150 feet off Burnt Gin Road by a hunter at about 4 p.m. on Nov. 16 — a few S. GINTHER hours after she was reported SEE ARREST, PAGE A7 Attorney says mold at Morris causing illness BY BRUCE MILLS [email protected] The litigation attorney who filed a class-ac- tion suit on behalf of five current and former Morris College students against the college last week says the mold issues on the campus are “toxic” and that he wants the col- lege to step up and fix the prob- lems. Attorney John Harrell of Har- rell Law Firm, PA, in Charleston, made his comments Monday con- cerning the case after the lawsuit HARRELL was filed last week and the JIM HILLEY / THE SUMTER ITEM college was notified. -

Football Media Guide 2010

Wofford College Digital Commons @ Wofford Media Guides Athletics Fall 2010 Football Media Guide 2010 Wofford College. Department of Athletics Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/mediaguides Recommended Citation Wofford College. Department of Athletics, "Football Media Guide 2010" (2010). Media Guides. 1. https://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/mediaguides/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at Digital Commons @ Wofford. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Guides by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Wofford. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TTHISHIS ISIS WOFFORDWOFFORD FFOOOOTTBALLBALL ...... SEVEN WINNING SEASONS IN LAST EIGHT YEARS 2003 AND 2007 SOCON CHAMPIONS 2003, 2007 AND 2008 NCAA FCS PLAYOFFS ONE OF THE TOP GRADUATION RATES IN THE NATION 2010 NCAA PLAYO Football WOFFORDWOFFORD Media Guide 1990 1991 2003 2007 2008 ff S COntEntS 2010 SCHEDULE Quick Facts ...............................................................................2 Sept. 4 at Ohio University 7:00 pm Media Information ............................................................... 3-4 2010 Outlook ...........................................................................5 Sept. 11 at Charleston Southern 1:30 pm Wofford College ................................................................... 6-8 Gibbs Stadium ..........................................................................9 Sept. 18 UNION (Ky.) 7:00 pm Richardson Building ...............................................................10 -

Advancing Excellence

ADVANCING EXCELLENCE ADVANCING EXCELLENCE 2017 Advancing Excellence As the College of Media celebrates its 90th year, and the University of Illinois celebrates its 150th, we are reflecting on all of the accomplishments of our many distinguished alumni and the impact they have across the country and around the globe. The University of Illinois and the College of Media has much to be proud of, and as we look at the next 90 years, we know that our alumni and friends are at the center of what we will accomplish. We are thrilled to announce the public launch of to succeed, regardless of background or socioeconomic the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s status. We are confident that With Illinois will have a fundraising campaign “With Illinois,” and we are significant impact on our ability to fulfill this mission. excited about the impact the campaign will have on The exponential decreases in state funding for higher our campus, programs, students and faculty. With education in the past several years require us to rely Illinois is our most ambitious philanthropic campaign more heavily on private support to realize our mission. to date, and it will have transformative impact for Your support allows us to fulfill our commitment to generations to come. As we move forward with a tradition of excellence and we are grateful for your accomplishing the goals set forth by the campaign, partnership. we celebrate each of you who have already given so Please visit with.illinois.edu for more details regarding generously to the College of Media. Your investment the With Illinois campaign and media.illinois.edu/ in the college creates so many opportunities that would giving/withillinois for the College of Media’s campaign be out of reach for many of our students. -

Read the Full PDF

THE VIDEO CAMPAIGN Network Coverage of the 1988 Primaries ~ S. Robert Lichter, Daniel Amundson, and Richard Noyes rrJ T H E S 0 "Everybody talks about campaign journalism. Bob Lichter studies it and rrJ has for years. This time around, he studies it more closely and system 0 atically than anybody else in the field." -Michael Robinson Georgetown University "Bob Lichter and his team are the one source I know who are system atically studying the campaign news. I rely on them again and again." -Tom Rosenstiel i 0 Los Angeles Times :z nc Network Coverage :r R'., • of the ~ c :1 Co (I) 1988 Primaries 0 :1 :z• ~ ~ (I) ~ C'":l :::E US $12.00 :: u ~ ISBN-13: 978-0-8447-3675-4 ISBN-l0: 0-8447-3675-9 51200 AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE FOR P<lBUC POUCY RESEARCH @ CENTER FOR MEDIA AND P<lBUC AFFAIRS 9 780844 736754 eM K T * H * E VIDE CAMPAIGN CAMPAIGN Network Coverage of the 1988 Primaries s. Robert Lichter Daniel Amundson Richard Noyes AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE FOR PUBUC POUCY RESEARCH CENTER FOR MEDIA AND PUBUC AFFAIRS Distributed to the Trade by National Book Network, 15200 NBN Way, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 17214. To order call toll free 1-800-462-6420 or 1-717-794-3800. For all other inquiries please contact the'&-qJ Press, 1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 or call 1-800-862-5801. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lichter, S. Robert. The video campaign. (AEI studies ; 483) 1. Television in politics--United States. 2. -

C019 039 025 All.Pdf

----~------------------------ - This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu REMARKS OF SENATOR BOB DOLE INTERNATIONAL PLATFORM ASSOCIATION MAYFLOWER HOTEL, WASHINGTON, D.c. WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 7, 1985 THANKS VERY MUCH, DAN, FOR THAT GENEROUS INTRODUCTION. LET ME BEGIN BY EXPRESSING MY GRATITUDE FOR THIS AWARD. BEFORE I CAME OVER HERE, I DID A LITTLE RESEARCH INTO THEODORE ROOSEVELT'S CAREER, ESPECIALLY AS A PLATFORM ORATOR. FOR INSTANCE, WHEN HE WAS SHOT IN THE CHEST DURING THE 1912 BULL MOOSE CAMPAIGN, HE INSISTED ON DELIVERING A TWO-HOUR SPEECH BEFORE GOING TO THE HOSPITAL. AFTERWARDS, THE DOCTORS FOUND THAT IT WAS THE FOLDED UP MANUSCRIPT -- ABOUT 80 PAGES LONG -- WHICH SLOWED THE BULLET BEFORE IT COULD DO MORTAL DAMAGE. SO THERE YOU HAVE AT LEAST ONE EXAMPLE OF WHERE LONGWINDEDNESS SAVED SOMEONE'S LIFE. FROM MY OWN EXPERIENCE, IT'S MORE LIKELY TO SHORTEN LIFE. Page 1 of 58 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu - 2 - WHY DO WE REMEMBER ROOSEVELT WITH SO MUCH AFFECTION? CERTAINLY, FEW MEN IN THE HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC EVER ENJOYED THEIR TIME IN POWER MORE. FEW GAVE OFF A MORE EFFORTLESS IMPRESSION OF COMMAND. FEW CONVEYED WITH SUCH ELOQUENCE THE COMBINATION OF PERSONAL VALUES AND A NATIONAL VISION. IT WAS, AFTER ALL, THEODORE ROOSEVELT WHO INSISTED ON THE PRESIDENCY AS THE GREAT "BULLY PULPIT" OF POPULAR DEMOCRACY. AND FEW MEN, BEFORE OR SINCE, HAVE OCCUPIED THAT PULPIT WITH SUCH GUSTO. AS A REPUBLICAN, I ALSO THINK OF ROOSEVELT AS, IN MANY WAYS, THE FATHER OF MY PARTY IN THE 20TH CENTURY. -

Extensions of Remarks E2131 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

November 30, 2011 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E2131 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS INTRODUCTION OF H.R. 3521, THE the drivers of the debt and pro-growth solu- firefighters and their families. He chaired the ‘‘EXPEDITED LINE-ITEM VETO tions to create a more conducive environment National Fallen Firefighters Foundation at a AND RESCISSIONS ACT OF 2011’’ for job creation. time when we lost so many brave first re- This bipartisan legislation takes a modest sponders in the September 11 attacks. Hal HON. CHRIS VAN HOLLEN step in the right direction. The Expedited Line- was a champion for the families of firefighters Item Veto and Rescissions Act gives the OF MARYLAND who lost their lives in service to their commu- President an important tool to target unjustified nities, and he fought for and won the passage IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES spending, while also protecting Congress’s of legislation to provide them survivor benefits. Wednesday, November 30, 2011 constitutional authority to make spending deci- I know that Hal will be both dearly missed Mr. VAN HOLLEN. Mr. Speaker, today I join sions. and dearly remembered by many in govern- my friend House Budget Committee Chairman This new authority would allow the Presi- ment, those who turned to him for their news RYAN to introduce the ‘‘Expedited Line-Item dent to specify spending provisions within an for so many years, and by the families of fire- Veto and Rescissions Act of 2011.’’ Taxpayers appropriations bill, requiring stand-alone con- fighters on whose behalf he worked so tire- deserve a system that is accountable, and this sideration of the spending proposal by Con- lessly. -

Mark Hamrick, President, National Press Club

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH BRENT SCOWCROFT, NATIONAL SECURITY ADVISOR SUBJECT: GERALD R. FORD PRESIDENTIAL FOUNDATION JOURNALISM AWARDS MODERATOR: MARK HAMRICK, PRESIDENT, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, HOLEMAN LOUNGE, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 12:30 P.M. EDT DATE: TUESDAY, JUNE 14, 2011 (C) COPYRIGHT 2008, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, 529 14TH STREET, WASHINGTON, DC - 20045, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FOR INFORMATION ON BECOMING A MEMBER OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, PLEASE CALL 202-662-7505. MARK HAMRICK: (Sounds gavel.) Good afternoon, and welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Mark Hamrick with the Associated Press, and I’m 104th President of the Press club. We are the world’s leading professional organization for journalists, committed to our profession’s future through our programming, events such as this, while also working to foster a free press worldwide. For more information about the National Press Club, please visit our website at www.press.org. And, to donate to programs offered to the public through our Eric Friedheim National Journalism Library, website there, www.press.org/library. So, on behalf of our members worldwide, I’d like to welcome our speakers, as well as those of you attending today’s event. Our head table includes guests of the speaker, as well as working journalists who are also Club members. -

Send in More Cops LBJ's State of Union Message

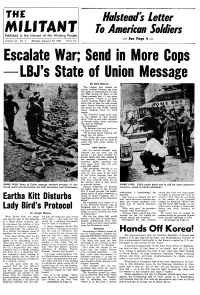

UntalftHINIIIHIItHIIIIUtiiHitiiUIIUIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIlllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllnllltlllllllfHHINftiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiUIIIIIIIIIIIHIItllllllllllllllltllllllllllllllfiiiiiiiiiUIIIIIIIIUtllfllllllllllllllllttulllllltllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll. THE Holsteotl's Letter MILITANT To Amerimn Soldiers Published in the Interest of the Working People -See Page 4- Volume 32 -No. 5 Monday, January 29, 1968 Price lOc llllllllllllllllllllllllfllllllllllll1iH11tlllllllllllltlllllllllllltlln.tiiiiiii11111111111111111111111U111111111111111111111111111111111111liiiUIIUIIUIIIIII!IUHUIIHII!IIIIIIIHHIIIII!Itlii!HIIIIUIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIUIIIIIIIIUIIIIII!l!iUIIHHII11!11111111111111111111111111111111111111UI Escalate War; Send in More Cops LBJ's State of Union Message By Dick Roberts The longest and loudest ap plause Lyndon Johnson got from the gang of reactionaries on Cap itol Hill during his State of the Union message Jan. 17 was when he declared: "There is no more urgent business before this Con gress than to pass the safe streets acts." Every cheering racist pres ent knew he was really talking about cracking down on black people. The President spent more time on the subject of "law enforce ment" than on any other domestic or foreign policy issue, including the war in Vietnam. He promised: "To develop state and local mas ter plans to combat crime. "To provide better training and better pay for police. "To bring the most advanced technology to the war on crime in every city and every county in America." Only Answer For the second straight year, Johnson did not even pay lip service to the black struggle for human rights. His only answer to the demands expressed in last summer's ghetto uprisings was more guns, more cops, and even more FBI agents. One paragraph devoted to re· inforcing the FBI by 100 men took up more space in the State of the Union message than the plight of the nation's farmers, who have recently been hit by the sharpest drop in farm prices MORE WAR. -

The Rise and Demise of Confidential Magazine

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 25 (2016-2017) Issue 1 Article 4 October 2016 The Most Loved, Most Hated Magazine in America: The Rise and Demise of Confidential Magazine Samantha Barbas Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Repository Citation Samantha Barbas, The Most Loved, Most Hated Magazine in America: The Rise and Demise of Confidential Magazine, 25 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 121 (2016), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmborj/vol25/iss1/4 Copyright c 2016 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj THE MOST LOVED, MOST HATED MAGAZINE IN AMERICA: THE RISE AND DEMISE OF CONFIDENTIAL MAGAZINE Samantha Barbas * INTRODUCTION Before the National Enquirer , People , and Gawker , there was Confidential . In the 1950s, Confidential was the founder of tabloid, celebrity journalism in the United States. With screaming headlines and bold, scandalous accusations of illicit sex, crime, and other misdeeds, Confidential destroyed celebrities’ reputations, relation- ships, and careers. Not a single major star of the time was spared the “Confidential treatment”: Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, Liberace, and Marlon Brando, among others, were exposed in the pages of the magazine. 1 Using hidden tape recorders, zoom lenses, and private investigators and prostitutes as “informants,” publisher Robert Harrison set out to destroy stars’ carefully constructed media images, and in so doing, built a media empire. Between 1955 and 1957, Confidential was the most popular, bestselling magazine in the nation.