The International Baccalaureate in Remote Indonesian Contexts: a Global to Local Curriculum Policy Trajectory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Certification 1 INDIGENOUS STUDENT SUCCESS PROGRAMME – 2018 Performance

INDIGENOUS STUDENT SUCCESS PROGRAMME – 2018 Performance Report Organisation The University of Western Australia Contact Person Professor Jill Milroy Phone (08) 6488 7829 E-mail [email protected] Acknowledgment of Noongar People and Land The University of Western Australia acknowledges that it is situated on Noongar land. Noongar people remain the spiritual and cultural custodians of their land and continue to practice their values, languages, beliefs and customs. 1. Enrolments (Access) Table 1: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Student Enrolments at UWA 2016-2018 2016 2017 2018 Headcount EFTSL Headcount EFTSL Headcount EFTSL Commencing Aboriginal & Torres Strait IslanDer stuDents Regional 13 11.0 14 12.3 15 10.8 Remote 27 22.9 25 18.8 24 18.3 Other 69 55.1 63 47.6 55 41.6 Total 109 89.0 102 78.6 94 70.6 Total Aboriginal & Torres Strait IslanDer stuDents Regional 30 24.4 33 25.8 37 24.4 Remote 61 47.3 52 38.1 50 36.0 Other 170 130.4 172 120.0 155 120.1 Total 261 202.0 257 183.9 242 180.5 (Source: EIS; fy_enrol_2019 by Student; and fy_load_2015-19_id) The Commonwealth Performance Data shows that UWA’s Position within the national rankings is mixeD. UWA’s ranking for InDigenous stuDents from regional anD remote areas has DroPPeD but remains in the toP 50% of rankings anD while our ranking for total InDigenous stuDent load/EFTSL has improved slightly in 2016, we have droppeD in the Progression/Success Rate ranking which is more complex anD we will neeD to look at this area closely. -

Indigenous Student Success Program 2019 Performance Report

Indigenous Student Success Program 2019 Performance Report Organisation The University of Western Australia Contact Person Professor Jill Milroy Phone (08) 6488 7829 E-mail [email protected] Acknowledgment of Noongar People and Land The University of Western Australia acknowledges that it is situated on Noongar land. Noongar people remain the spiritual and cultural custodians of their land and continue to practice their values, languages, beliefs and customs. 1. Enrolments (Access) The Commonwealth performance data for 2017 shows that UWA’s position within the national rankings is mixed. UWA’s ranking for total Indigenous student load/EFTSL dropped slightly from our 2016 position. Our ranking for Indigenous students from regional and remote areas has just dropped outside the top 50% of rankings, but our Indigenous regional and remote students as percentage of all Indigenous students has increased. Our Success Rate ranking has remained steady and we are developing strategies to increase this. A number of actions and strategies to mitigate further drops in UWA’s Indigenous total load have been identified, but will take some time to have an impact. Since 2017 we have increased the number of commencing students as well as the access rate for 2017-2019 (from 1.54 to 1.71). Recruiting Indigenous school leavers remains a priority but the pool of potential students, particularly ATAR students is relatively small. The Department of Education Annual Report 2018 – 2019, shows that in 2018 for government schools only 60 Indigenous year 12 school leavers (8.3% of the cohort) achieved an ATAR. While maintaining our strong commitment to school leavers and regional students, key priority and target areas are increasing Indigenous postgraduate coursework enrolments, particularly in professional courses and building Indigenous HDR enrolments. -

2020-Indigenous-Nationals-Flyer.Pdf

June 28 UniSport Indigenous – 2 July Nationals Newcastle, NSW 2020 The Indigenous Nationals is an annual, week-long multisport competition for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students studying at University from all over Australia. The Indigenous Nationals is held annually at different universities around Australia. This year, the event will be held at The Wollotuka Institute at The University of Newcastle and gives students a great opportunity to travel and compete with your team in an amazing environment that celebrates the rich sporting culture of Indigenous Australians. By participating in the games, you will not only get the opportunity to compete and represent ECU, but you will also get to network with Indigenous students and staff from all parts of Australia in the many social events that are held during the week. Teams will be made up of between 10 to 16 athletes and will compete across four codes: basketball, netball, volleyball and touch football. Being part of the ECU Indigenous team was a blast, forming a team and getting to know each other like family over an intense week sharing university experiences through sport. Student Testimony – 2019 captain and National MVP Luke Turner To find out more, please attend one of the following sessions. „ “Tryout and Information Sessions Location Date ECU Mount Lawley Sports Centre Wed 19 February 2:00pm (tryout) ECU Joondalup Sports Centre Thu 20 February 2:00pm (tryout) Kurongkurl Katitjin Family Day Mt Lawley Mon 2 March 11:00am (information stall) Cost As the team will be travelling interstate there will be a cost incurred per student. -

Cook Islands

Capturing Wealth from Tuna Key Issues for Pacific Island Countries COUNTRY PROFILES Kate Barclay Ian Cartwright June 2006 Capturing Wealth From Tuna Country Profiles © Copyright 2006, Kate Barclay and Ian Cartwright Photograph on Cover Soltai Fishing and Processing Ltd pole-and-line fishing vessel, Noro, Solomon Islands. Photograph taken by Kate Barclay July 2005. 2 Capturing Wealth From Tuna Country Profiles Table of Contents Cook Islands...................................................................................................................5 Tuna Fisheries in Cook Islands..................................................................................5 Development Aspirations and Tuna.........................................................................23 Issues Affecting Pacific Island Bloc Cooperation within the WCPFC....................29 Details of Fisheries and Processing .........................................................................33 Fiji................................................................................................................................37 Tuna Fisheries in Fiji ...............................................................................................37 Development Aspirations and Tuna.........................................................................57 Issues Affecting Pacific Island Bloc Cooperation within the WCPFC....................64 Details of Fisheries and Processing .........................................................................67 Kiribati .........................................................................................................................71 -

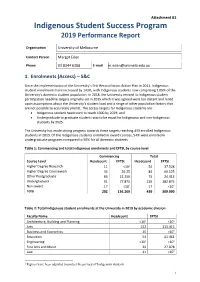

Indigenous Student Success Program 2019 Performance Report

Attachment B1 Indigenous Student Success Program 2019 Performance Report Organisation University of Melbourne Contact Person Margot Eden Phone 03 8344 6388 E-mail [email protected] 1. Enrolments (Access) – S&C Since the implementation of the University’s first Reconciliation Action Plan in 2011, Indigenous student enrolments have increased by 143%, with Indigenous students now comprising 1.05% of the University’s domestic student population. In 2018, the University revised its Indigenous student participation headline targets originally set in 2015 which it was agreed were too distant and relied upon assumptions about the University’s student load and a range of other population factors that are not possible to accurately predict. The access targets for Indigenous students are: ñ Indigenous student headcount to reach 1000 by 2029; and ñ Undergraduate to graduate student ratio to be equal for Indigenous and non-Indigenous students by 2025. The University has made strong progress towards these targets reaching 439 enrolled Indigenous students in 2019. Of the Indigenous students enrolled in award courses, 54% were enrolled in undergraduate programs compared to 50% for all domestic students. Table 1: Commencing and total Indigenous enrolments and EFTSL by course level Commencing Total Course Level Headcount EFTSL Headcount EFTSL Higher Degree Research 11 <101 54 37.528 Higher Degree Coursework 34 26.25 84 60.125 Other Postgraduate 63 21.250 75 24.313 Undergraduate 91 77.875 226 182.875 Non-award 17 <101 17 <101 Total 202 136.269 439 309.090 Table 2: Total Indigenous student enrolments at the University in 2019 by academic division Faculty Name Headcount EFTSL Architecture, Building and Planning <101 <101 Arts 152 113.413 Business and Economics 15 <101 Education 54 21.461 Engineering <101 <101 Fine Arts and Music 34 27.878 Law 11 <101 1 Figures have been adjusted to protect the privacy of Indigenous students. -

Bp Australia Awards Two Scholarships to Indigenous Students

press release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THURSDAY 16 MAY 2019 BP AUSTRALIA AWARDS TWO $5,000 SCHOLARSHIPS TO INDIGENOUS STUDENTS BP Australia presented $5,000 scholarships to two promising Indigenous student-athletes (male and female) at the UniSport Australia gala dinner awards last night in Melbourne. Congratulations to the scholarship recipients, Jasper John, a Nyikina man from the Kimberley region of Western Australia who has relocated to Perth to study, and Asha Steer, a Barkanji woman currently studying at The University of Melbourne. In addition to the financial assistance, the scholarship recipients will also be offered mentoring and professional development opportunities with BP Australia. Richard Swyny, HR Director BP Australia & New Zealand, said BP was honoured to be supporting young, talented Indigenous students with their academic and athletic endeavours. “We established our partnership with UniSport and designed this scholarship programme to connect with Indigenous students, support the next generation of talented individuals, and to demonstrate our commitment to building a diverse workforce across Australia,” said Swyny. “We are thrilled with the response we had to the scholarship programme in its first year. We thank everyone who applied and wish all the students the best for the future.” Student, Barkanji woman, and orienteering champion, Asha Steer, said: “This means a lot to me, not only for the generous financial award but also for the recognition of my sport and the opportunity to represent Aboriginal people in such an influential way.” The scholarship programme is one component of BP Australia’s new partnership with UniSport Australia. The organisations will come together again next month to present the 2019 Indigenous Nationals, hosted in Perth by The University of Western Australia on 23 - 27 June 2019. -

Office Bearer Reports 9(18)

Office Bearer Reports – Students’ Council, Meeting 10(18) University of Melbourne Student Union Meeting of the Students’ Council Student Office Bearer Reports 11:30am, Thursday, the 24th of May, 2018 Meeting 10(18) Location: Joe Napolitano A, Second Floor, Union House Student Office Bearer Reports President Submitted General Secretary Submitted Activities Submitted Clubs & Societies Submitted Creative Arts Submitted Disabilities Submitted Education (Academic Affairs) Submitted Education (Public Affairs) Submitted Environment Submitted Indigenous Submitted Media Submitted People of Colour Submitted Queer Submitted Welfare Submitted Women’s Submitted Burnley Submitted Victorian College of the Arts Vacant All Office Bearer Reports are presented as they were received, with only formatting changes. Late reports are not considered valid. 1 Office Bearer Reports – Students’ Council, Meeting 10(18) President Desiree Cai Key Activities Student Precinct On the 11th of May, Daniel, UMSU Management, and I attended a meeting about UMSU within the Student Precinct’s concept design. There were a range of issues that were noted in the design, as well as in the accommodation schedule (table of UMSU spaces and sizes) that the precinct team had been using. While the precinct team has assured us that many of these design issues and concerns UMSU has will be dealt with in the Schematic Design Phase which will be starting soon, there are some issues that are still outstanding. These include a lack of a space allocation for the Student Bar, continuing confusion about what ‘retail’ ground floor space UMSU will be allocated, and concerns about the visibility and connectiveness of UMSU spaces and the Rowden White Library throughout the precinct. -

2020 Unisport Australia Events Calendar

2020 UniSport Australia Events Calendar Date Start Date End Event Name Location Organiser UniSport Section Sun 15 Mar Sun 15 Mar UniSport 2020 Nationals Triathlon Mooloolaba UniSport / Nationals Wed 18 Mar Wed 18 Mar UniSport East Team Forum Macquarie UniSport Member Services Fri 3 Apr Sun 5 Apr UniSport 2020 Nationals Athletics Brisbane UniSport / Nationals Thur 16 Apr Fri 17 Apr UniSport 2020 Nationals 3x3 Basketball (FISU Qualifiers) Canberra UniSport / Hustle Nationals TBC Apr TBC Apr UniSport 2020 League of Legends Sydney UniSport / Nationals Wed 13 May Fri 15 May UniSport 2020 National Conference Sydney UniSport Member Services Thur 14 May Sun 17 May UniSport 2020 Nationals Swimming Sydney UniSport / Nationals Sun 28 Jun Thur 2 July UniSport 2020 Indigenous Nationals Newcastle UniSport / NCLE Nationals Tues 30 Jun Tues 30 Jun UniSport East Team Forum Newcastle UniSport Member Services Thur 6 Aug Thur 6 Aug UniSport 2020 Nationals Cheer & Dance Melbourne UniSport / Nationals Wed 26 Aug Wed 26 Aug UniSport East Team Forum Wollongong UniSport Member Services Sun 6 Sept Thur 10 Sept UniSport 2020 Nationals Snow Mt. Buller UniSport Nationals Sat 26 Sept Fri 2 Oct UniSport 2020 Nationals Div 1 & Div 2 Perth UniSport Nationals AFL, Badminton, Baseball (Open), Basketball, Beach Volleyball, Cycling, Fencing, Football, Futsal, Handball (Mixed), Hockey, Judo, Kendo, Lacrosse 5s (Open), Lawn Bowls (Open), Netball, Rowing, Rugby 7s, Sailing (Open), Softball (Women), Squash, Table Tennis, Taekwondo, Tennis, Tenpin Bowling (Open), Touch, Ultimate -

Newsletter Ngarara Willim

RMIT UNIVERSITY NGARARA WILLIM NEWSLETTER ISSUE 9 FEBRUARY 2021 Remembering Uncle Colin Bourke On behalf of the Ngarara Willim team it is Colin did not fail with great sadness that we share the passing to live up to those of Emeritus Professor Colin Bourke, MBE expectations. on the 10 February, aged 84. Colin was a Alongside an life member of the National Aboriginal and unwavering Torres Strait Islander Higher Education commitment Consortium (NATSIHEC) due to the significant to employing contributions he made to Aboriginal and Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander higher Education and to people or what Education more broadly. Colin called ‘Aboriginalisation’ Colin’s leadership and scholarship paved the he also continued way for the educational opportunities we have a Black Studies access to today. His advocacy and leadership as program which an inaugural member of the National Aboriginal gave voice and a Education Committee (NAEC) laid the foundations platform to a number of prominent Indigenous for NATSIHEC. It’s his shoes and the shoes of community members. Realising limitations Colin the many other pioneers that we need to try to began working closely with another titan of our fill in our role as advocates for our communities. space and his future wife Eleanor Bourke who was working at the University of Melbourne. Colin built a ladder that he left for all of us to Through an important collaboration they follow and he did this with community and inside provided a platform for Indigenous speakers. the Education system. He represented many For Colin and Eleanor, this work provided a firsts for Aboriginal people, starting his career crucial platform for Aboriginal perspectives and as a primary school teacher he went on to firsthand information about our communities. -

48Winter 2021

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF SYDNEY UNI SPORT & FITNESS susf.com.au ROARWINTER 48 2021 10 BREAKING BARRIERS 22 SEVENS HEAVEN 24 BATTLE OF THE RESIDENCES FLYING HIGHSUSF.COM.AU A CELEBRATING OUR RETURNING STUDENT ATHLETES, SCHOLARSHIP HOLDERS, CLUB MEMBERS AND GRADUATES WHO COMPETED AT THE TOKYO OLYMPIC GAMES. WISHING OUR ATHLETES THE BEST OF LUCK FOR THE UPCOMING PARALYMPIC GAMES. ROAR CREDITS EDITOR Nicole Safi WINTER DEPUTY EDITORS Anastasia Barrat 48 2021 Graham Croker CONTENTS Sera Naiqama CREATIVE DESIGN & PRODUCTION Southern Design CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Anastasia Barrat Emma Hogan Graham Croker Nicole Safi Sera Naiqama FROM THE EDITOR Tracy McBeth Trudie McConnochie CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS The curtain has drawn on the Tokyo Olympic Games, which dazzled the world for two 06 10 20 spectacular weeks. Casey Sims Karen Spencer (Mum’s Rugby Snaps) MEMBER MEETS: BREAKING BARRIERS DEAD HEAT DUO The timing of the postponed Olympic Games could not have been more perfect for CHRIS SMITH us sport-mad Aussies. Locked down at home as the country faces its own competition against the Delta variant of the coronavirus, most of us watched more of the Olympics SYDNEY UNI By Sera Naiqama By Sera Naiqama By Graham Croker than we otherwise would’ve been able to. SPORT & FITNESS The joy of medals won, records broken and dreams realised; the Games served as a timely reminder that sport knows no bounds – people of all ages, races, creeds, MANAGEMENT abilities, nationalities, and sexual orientation are equipped not only to participate in sport, but to succeed in it. CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Ed Smith Bachelor of Science student and Sydney University Athletics Club high jumper Nicola McDermott features on the cover of this edition of ROAR Magazine. -

2019 Performance Report and Financial Acquittal

ISSP Performance Report 2019 Letter of Offer and Attachments Professor Rufus Black Vice-Chancellor and President University of Tasmania Private Bag 51 SANDY BAY TAS 7001 Dear Professor Black I am pleased to provide you with documentation regarding participation in the Indigenous Student Success Program (ISSP) in 2019. The ISSP offers eligible providers supplementary assistance to increase the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students enrolling in, progressing in and completing higher education awards. Please find attached: 1. Your institution’s estimated 2019 entitlement (Attachment A). A first payment of 50 per cent of this estimated entitlement is expected to be made to your nominated bank account in February 2019. A second ISSP payment is expected to be paid in July 2019 after reassessing entitlements considering unused preserved scholarships. 2. Data on your institution’s past performance, as well as how your institution compares to other participating providers (Attachment B). 3. Performance and financial reporting templates to acquit 2019 ISSP activity (Attachment C). These need to be completed and returned to the Department by 30 April 2020. Program eligibility All participating ISSP providers are required to maintain an Indigenous Education Strategy, an Indigenous Workforce Strategy and an Indigenous Governance Mechanism during 2019 to remain eligible for funding under ISSP. If at any time during the year the institution does not have these in place, you should notify the Department within 30 days so a plan can be agreed to meet these eligibility requirements. Senator the Hon Nigel Scullion, Minister for Indigenous Affairs, has expressed concern about the lack of apparent planning by some universities in ensuring continuity in meeting the basic requirements of Indigenous Education and Workforce Strategies set out for ISSP eligibility. -

Ben Rennie Photography

Photo by: Ben Rennie Photography CONTENTS JCU Student Association recognises the Traditional Owners as the original 4 5 6 custodians of the land on which all Australian James ABOUT STUDENT STUDENT Cook University campuses sit. JCUSA COUNCIL PRESIDENT Further recognition is made & STAFF that: • Traditional Owners have a unique status as the descendants of the land; • Traditional Owners have 8 10 24 a spiritual, social, cultural GENERAL STUDENT STUDENT and economic relationship MANAGER COUNCIL ADVOCATE with their traditional lands REPORTS REPORTS and waters within this area. • Traditional Owners have made a unique and irreplaceable contribution to the identity and wellbeing of this land. 31 38 42 EVENTS CLUBS SPORT • Respect for Traditional REPORT REPORT REPORT Owners and the acknowledgement of Elders past and present must be a core value of our operation. 48 52 54 MEDIA ELECTION FINANCIAL REPORT REPORT REPORT ABOUT JCUSA James Cook University Student Association (JCUSA) is an organisation directed by elected and appointed Office Bearers, which aims to provide high quality representation, support services and relevant non- academic activities to all of its members. The services that JCUSA provide include: • Student representation • Academic advocacy & Welfare Services • Administration of student Clubs, Societies and Associations • Student Events & Activities • Student Managed Communication & Media, including the Student Bullsheet Under the JCUSA Constitution, the objectives of the Association are: • to promote interest in the life, activities