A Study of Dynamics of Himmat Shah's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Delhi on the Second Consecu- “Seriously Damaging Impact” Imise Extremist Activism,” the December 7, Awards Will Be Tive Day

( B2 $ A # '% C % C C VRGR '%&((!1#VCEB R BP A"'!#$#1!$"#0$"T utqBVQWBuxy( 35&63% ., 2$1213 42 , 5$2 /6 A $/4O2"EE H-2-5587"E/824/5-7&E-2&/4 &4$&-"-2-8E9 $"71&780?4/6 1/A-718-4"E6-5 6&21-5"5E /&E5-"72&"E/54/6 584E&4E22,> 5-401&5-&A85 01-4$&3-51 $"15-$84 19$"5--$ &G-96-$- D7 0 $2+>334 ++: D-E " #- 7 ) " 0 1-1- ! 1/ R R R ! " ( ! 4"6$"71& soon. In the meeting tomorrow our main agenda will be to he farmers on Friday called know if the Government is Tfor “Bharat Bandh” on rolling back laws or not. The December 8 to mark their protests are going on country- authorities to highlight our protest against the new farm wide against the law, even in # # # concerns.” laws if their talks with the Andhra Pradesh and Telangana Q % & R The External Affairs Centre fail. Thousands of farm- and this protest is just not lim- Ministry said these comments ers remained at the national ited to northern States but have encouraged gatherings of Capital’s border points amid across the country,” said '() “extremist activities” in front of heavy police deployment. Ranjeet Singh Raju from our High Commission and “The Government has to Rajasthan. 4"6$"71& Consulates in Canada that raise revoke these laws in a meeting Farmers from western issues of safety and security. scheduled for December 5, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand tepping up its protest against “We expect the Canadian otherwise we have decided to stayed put at Ghazipur border SCanadian Prime Minister Government to ensure the give ‘Bharat bandh’ call on (UP Gate) to mark their Justin Trudeau’s remarks about fullest security of Indian December 8 and we will also protest. -

Contemporary Art in Indian Context

Artistic Narration, Vol. IX, 2018, No. 2: ISSN (P) : 0976-7444 (e) : 2395-7247Impact Factor 6.133 (SJIF) Contemporary Art in Indian Context Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai Richa Singh Asso. Prof., Research Scholar Deptt. of Drawing & Painting M.F.A. M.M.H. College B.Ed. Ghaziabad, U.P. Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Abstract: This article has a focus on Contemporary Art in Indian context. Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai Through this article emphasizesupon understanding the changes in Richa Singh, Contemporary Art over a period of time in India right from its evolution to the economic liberalization period than in 1990’s and finally in the Contemporary Art in current 21st century. The article also gives an insight into the various Indian Context, techniques and methods adopted by Indian Contemporary Artists over a period of time and how the different generations of artists adopted different techniques in different genres. Finally the article also gives an insight Artistic Narration 2018, into the current scenario of Indian Contemporary Art and the Vol. IX, No.2, pp.35-39 Contemporary Artists reach to the world economy over a period of time. key words: Contemporary Art, Contemporary Artists, Indian Art, 21st http://anubooks.com/ Century Art, Modern Day Art ?page_id=485 35 Contemporary Art in Indian Context Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai, Richa Singh Contemporary Art Contemporary Art refers to art – namely, painting, sculpture, photography, installation, performance and video art- produced today. Though seemingly simple, the details surrounding this definition are often a bit fuzzy, as different individuals’ interpretations of “today” may widely vary. -

Syllabus of Arts Education

SYLLABUS OF ARTS EDUCATION 2008 National Council of Educational Research and Training Sri Aurobindo Marg, New Delhi - 110016 Contents Introduction Primary • Objectives • Content and Methods • Assessment Visual arts • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Theatre • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Music • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Dance • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Heritage Crafts • Higher Secondary Graphic Design • Higher Secondary Introduction The need to integrate art s education in the formal schooling of our students now requires urgent attention if we are to retain our unique cultural identity in all its diversity and richness. For decades now, the need to integrate arts in the education system has been repeatedly debated, discussed and recommended and yet, today we stand at a point in time when we face the danger of lo osing our unique cultural identity. One of the reasons for this is the growing distance between the arts and the people at large. Far from encouraging the pursuit of arts, our education system has steadily discouraged young students and creative minds from taking to the arts or at best, permits them to consider the arts to be ‘useful hobbies’ and ‘leisure activities’. Arts are therefore, tools for enhancing the prestige of the school on occasions like Independence Day, Founder’s Day, Annual Day or during an inspection of the school’s progress and working etc. Before or after that, the arts are abandoned for the better part of a child’s school life and the student is herded towards subjects that are perceived as being more worthy of attention. General awareness of the arts is also ebbing steadily among not just students, but their guardians, teachers and even among policy makers and educationalists. -

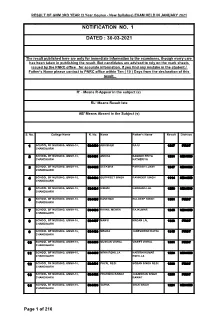

Notification No. 1 Dated : 30-03-2021

RESULT OF GNM 3RD YEAR (3 Year Course - New Syllabus) EXAM HELD IN JANUARY 2021 NOTIFICATION NO. 1 DATED : 30-03-2021 The result published here are only for immediate information to the examinees, though every care has been taken in publishing the result. But candidates are advised to rely on the mark sheets issued by the PNRC office for accurate information. If you find any mistake in the student / Father's Name please contact to PNRC office within Ten ( 10 ) Days from the declaration of this result. R' - Means R-Appear in the subject (s) RL' Means Result late AB' Means Absent in the Subject (s) S. No. College Name R. No. Name Father's Name Result Division 1 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534480 ABHISHEK RAJU 1287 FIRST CHANDIGARH 2 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534481 ANKITA BAUDDH PRIYA 1231 SECOND CHANDIGARH KATHERIYA 3 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534482 DEEKSHA PARKASH LUXMI 1247 SECOND CHANDIGARH 4 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534483 GURPREET SINGH RAVINDER SINGH 1114 SECOND CHANDIGARH 5 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534484 HIMANI HARBANS LAL 1250 SECOND CHANDIGARH 6 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534485 KANCHAN KULDEEP SINGH 1381 FIRST CHANDIGARH 7 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534486 KHANIL MEHRA RAJKUMAR 1245 SECOND CHANDIGARH 8 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534487 MANSI MADAN LAL 1338 FIRST CHANDIGARH 9 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534488 MEGHA JANESHWAR DAYAL 1315 FIRST CHANDIGARH 10 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534489 MUSKAN VISHAL VINEET VISHAL 1301 FIRST CHANDIGARH 11 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534490 NEHA ROHILLA NARESH KUMAR 1223 SECOND CHANDIGARH ROHILLA 12 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534491 PAYAL NEGI SOBAN SINGH NEGI 1296 FIRST CHANDIGARH 13 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534492 PRATIBHA RAWAT JAGMOHAN SINGH 1266 FIRST CHANDIGARH RAWAT 14 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534493 SAPNA SHER SINGH 1221 SECOND CHANDIGARH Page 1 of 216 RESULT OF GNM 3RD YEAR (3 Year Course - New Syllabus) EXAM HELD IN JANUARY 2021 S. -

Current Affairs 2013- January International

Current Affairs 2013- January International The Fourth Meeting of ASEAN and India Tourism Minister was held in Vientiane, Lao PDR on 21 January, in conjunction with the ASEAN Tourism Forum 2013. The Meeting was jointly co-chaired by Union Tourism Minister K.Chiranjeevi and Prof. Dr. Bosengkham Vongdara, Minister of Information, Culture and Tourism, Lao PDR. Both the Ministers signed the Protocol to amend the Memorandum of Understanding between ASEAN and India on Strengthening Tourism Cooperation, which would further strengthen the tourism collaboration between ASEAN and Indian national tourism organisations. The main objective of this Protocol is to amend the MoU to protect and safeguard the rights and interests of the parties with respect to national security, national and public interest or public order, protection of intellectual property rights, confidentiality and secrecy of documents, information and data. Both the Ministers welcomed the adoption of the Vision Statement of the ASEAN-India Commemorative Summit held on 20 December 2012 in New Delhi, India, particularly on enhancing the ASEAN Connectivity through supporting the implementation of the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity. The Ministers also supported the close collaboration of ASEAN and India to enhance air, sea and land connectivity within ASEAN and between ASEAN and India through ASEAN-India connectivity project. In further promoting tourism exchange between ASEAN and India, the Ministers agreed to launch the ASEAN-India tourism website (www.indiaasean.org) as a platform to jointly promote tourism destinations, sharing basic information about ASEAN Member States and India and a visitor guide. The Russian Navy on 20 January, has begun its biggest war games in the high seas in decades that will include manoeuvres off the shores of Syria. -

Result of Gnm 1St Year Exam Held in December - 2018

RESULT OF GNM 1ST YEAR EXAM HELD IN DECEMBER - 2018 NOTIFICATION NO. 1 DATED : 31-05-2019 The result published here are only for immediate information to the examinees, though every care has been taken in publishing the result. But candidates are advised to rely on the mark sheets issued by the PNRC office for accurate information. If you find any mistake in the student / Father's Name please contact to PNRC office within Ten ( 10 ) Days from the declaration of this result. R' - Means R-Appear in the subject,(s) RL' Means Result late AB' Means Absent S. College Name Roll No Name Father Name Result No. 1 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483001 ABHISHEK RAJU 354 CHANDIGARH 2 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483002 ANKITA BAUDDH PRIYA 315 CHANDIGARH KATHERIYA 3 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483003 DEEKSHA PARKASH LUXMI 334 CHANDIGARH 4 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483004 GURPREET SINGH RAVINDER SINGH 312 CHANDIGARH 5 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483005 HIMANI HARBANS LAL 332 CHANDIGARH 6 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483006 KANCHAN KULDEEP SINGH 366 CHANDIGARH 7 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483007 KHANIL MEHRA RAJKUMAR 328 CHANDIGARH 8 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483008 MANSI MADAN LAL 356 CHANDIGARH 9 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483009 MEGHA JANESHWAR DAYAL 347 CHANDIGARH 10 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483010 MUSKAN VISHAL VINEET VISHAL 355 CHANDIGARH 11 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483011 NEHA ROHILLA NARESH KUMAR 324 CHANDIGARH ROHILLA 12 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483012 PAYAL NEGI SOBAN SINGH NEGI 346 CHANDIGARH Page 1 of 304 RESULT OF GNM 1ST YEAR EXAM HELD IN DECEMBER - 2018 S. -

Mehran-University-Of-Engineering-Technology-First-Merit-List2 0.Pdf

Full Name Father NameCNIC Enrollemt No.DepartmentCampus Year ofHSC Study percentageLast Exam PercentageCGPA Merit StatusStudent Selection Status Ahmed Bux Nadeem Ahmed4530327652261 CE17AR32 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 82.2 82.18 3.33 Selected Selected Student Khair MuhammadSohail Khalique4410188995737 F-CE17 AR22ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 82.1 82.09 3.33 Selected Selected Student Sohaib Qureshi Saifuddin Qureshi4150405257207 F-CE17-AR21ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 80.8 80.81 3.28 Selected Selected Student Touqeer Ul HaqueMohammad3810298220957 Arshad CE17AR23 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 80.5 80.54 3.27 Selected Selected Student Tamoor Ali Liquat Ali 4410650947793 CE17AR40 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 80.5 80.45 3.27 Selected Selected Student Ume Aeman Zulfiqar Ali 4120522942830 CE17AR02 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 80.2 80 3.26 Selected Selected Student GH zohra alias pashminaAbdul Raheem4530193395302 memon CE17AR35 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 78.1 78 3.18 Selected Selected Student Sana Laghari Allah Nawaz4410355870786 Laghari 47694 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 77.7 77.72 3.17 Not SelectedNot Selected Iraj Maira BughioNabi Bakhsh4130533257536 Bughio CE17AR38 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 77.8 77.81 3.17 Not SelectedNot Selected Farooq ahmed akhundJamil hyder akhund1412017560343 CE17AR30 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 77.2 77.18 3.15 Not SelectedNot Selected Awais Ahmed Shakeel Ahmed4510288215979 CE17AR39 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 76 76 3.1 Not SelectedNot Selected Aleeha Mehmood -

Catalogue Fair Timings

CATALOGUE Fair Timings 28 January 2016 Thursday Select Preview: 12 - 3pm By invitation Preview: 3 - 5pm By invitation Vernissage: 5 - 9pm IAF VIP Card holders (Last entry at 8.30pm) 29 - 30 January 2016 Friday and Saturday Business Hours: 11am - 2pm Public Hours: 2 - 8pm (Last entry at 7.30pm) 31 January 2016 Sunday Public Hours: 11am - 7pm (Last entry at 6.30pm) India Art Fair Team Director's Welcome Neha Kirpal Zain Masud Welcome to our 2016 edition of India Art Fair. Founding Director International Director Launched in 2008 and anticipating its most rigorous edition to date Amrita Kaur Srijon Bhattacharya with an exciting programme reflecting the diversity of the arts in Associate Fair Director Director - Marketing India and the region, India Art Fair has become South Asia's premier and Brand Development platform for showcasing modern and contemporary art. For our 2016 Noelle Kadar edition, we are delighted to present BMW as our presenting partner VIP Relations Director and JSW as our associate partner, along with continued patronage from our preview partner, Panerai. Saheba Sodhi Vishal Saluja Building on its success over the past seven years, India Art Senior Manager - Marketing General Manager - Finance Fair presents a refreshed, curatorial approach to its exhibitor and Alliances and Operations programming with new and returning international participants Isha Kataria Mankiran Kaur Dhillon alongside the best programmes from the subcontinent. Galleries, Vip Relations Manager Programming and Client Relations will feature leading Indian and international exhibitors presenting both modern and contemporary group shows emphasising diverse and quality content. Focus will present select galleries and Tanya Singhal Wol Balston organisations showing the works of solo artists or themed exhibitions. -

General Studies Series

IAS General Studies Series Current Affairs (Prelims), 2013 by Abhimanu’s IAS Study Group Chandigarh © 2013 Abhimanu Visions (E) Pvt Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system or otherwise, without prior written permission of the owner/ publishers or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act, 1957. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claim for the damages. 2013 EDITION Disclaimer: Information contained in this work has been obtained by Abhimanu Visions from sources believed to be reliable. However neither Abhimanu's nor their author guarantees the accuracy and completeness of any information published herein. Though every effort has been made to avoid any error or omissions in this booklet, in spite of this error may creep in. Any mistake, error or discrepancy noted may be brought in the notice of the publisher, which shall be taken care in the next edition but neither Abhimanu's nor its authors are responsible for it. The owner/publisher reserves the rights to withdraw or amend this publication at any point of time without any notice. TABLE OF CONTENTS PERSONS IN NEWS .............................................................................................................................. 13 NATIONAL AFFAIRS .......................................................................................................................... -

Credentialed Staff JHHS

FacCode Name Degree Status_category DeptDiv HCGH Abbas , Syed Qasim MD Consulting Staff Medicine HCGH Abdi , Tsion MD MPH Consulting Staff Medicine Gastroenterology HCGH Abernathy Jr, Thomas W MD Consulting Staff Medicine Gastroenterology HCGH Aboderin , Olufunlola Modupe MD Contract Physician Pediatrics HCGH Adams , Melanie Little MD Consulting Staff Medicine HCGH Adams , Scott McDowell MD Active Staff Orthopedic Surgery HCGH Adkins , Lisa Lister CRNP Nurse Practitioner Medicine HCGH Afzal , Melinda Elisa DO Active Staff Obstetrics and Gynecology HCGH Agbor-Enoh , Sean MD PhD Active Staff Medicine Pulmonary Disease & Critical Care Medicine HCGH Agcaoili , Cecily Marie L MD Affiliate Staff Medicine HCGH Aggarwal , Sanjay Kumar MD Active Staff Pediatrics HCGH Aguilar , Antonio PA-C Physician Assistant Emergency Medicine HCGH Ahad , Ahmad Waqas MBBS Active Staff Surgery General Surgery HCGH Ahmar , Corinne Abdallah MD Active Staff Medicine HCGH Ahmed , Mohammed Shafeeq MD MBA Active Staff Obstetrics and Gynecology HCGH Ahn , Edward Sanghoon MD Courtesy Staff Surgery Neurosurgery HCGH Ahn , Hyo S MD Consulting Staff Diagnostic Imaging HCGH Ahn , Sungkee S MD Active Staff Diagnostic Imaging HCGH Ahuja , Kanwaljit Singh MD Consulting Staff Medicine Neurology HCGH Ahuja , Sarina MD Consulting Staff Medicine HCGH Aina , Abimbola MD Active Staff Obstetrics and Gynecology HCGH Ajayi , Tokunbo Opeyemi MD Active Staff Medicine Internal Medicine HCGH Akenroye , Ayobami Tolulope MBChB MPH Active Staff Medicine Internal Medicine HCGH Akhter , Mahbuba -

Introduction to Indian Art Kl Lifestyle Art Space Presents 3 Indian Artists

INTRODUCTION TO INDIAN ART KL LIFESTYLE ART SPACE PRESENTS 3 INDIAN ARTISTS BY HIRANMAYII AWLI MOHANAN Indian art encompasses a variety of forms and originated about five thousand years ago, sometime during the peak of the Indus Valley civilisation. Largely influenced by a civilisation that came into existence in the 3rd millennium B.C., it blends the spiritual and the sensual, making it rather distinctive in form and appearance. However, progressively, Indian art has undergone several transformations and influenced by various cultures, making it more diverse and more inclusive of its people. PARITOSH SEN Paritosh Sen was a painter, illustrator, tutor and writer, who was a part of the world of Indian art, for close to four decades. He was born in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh on Oct 18, 1919 and was a founding member of the Calcutta Group — an art movement established in 1942 which played an important role in ushering modernism into Indian art. Allured by the pages of the Bengali art journal, Prabasi, Sen ran away to Madras, to learn art. Graduating with a Diploma in Fine Arts from the Government College of Arts and Crafts, Chennai, Sen moved to Calcutta in 1942, where he and a group of young Bengalis formed the Calcutta Group — an association of artists that sought to incorporate contemporary values in Indian art. In 1949, Sen left for Paris to pursue his passion, attending, among other institutes, the Ecole des Beaux Arts. He received a Fellowship for 1970-’71 from the John D. Rockefeller III Fund. The Indian artist’s visit to Paris in 1949 was what got him closer acquainted with European art and its artists.