Game After : a Cultural Study of Video Game Afterlife / by Raiford Guins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2003 Special 301 Report People’S Republic of China

INTERNATIONAL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ALLIANCE 2003 SPECIAL 301 REPORT PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Special 301 recommendation: With piracy losses at a staggering $1.85 billion in 2002, piracy rates continuing at over 90% across all copyright industries, and with no significant movement to enforce the criminal law against piracy as required by TRIPS, IIPA recommends that China remain subject to Section 306 Monitoring. Overview of key problems in China: More than one year following China’s WTO accession, piracy rates in China remain among the highest in the world. While enforcement actions throughout China continue, the apparent unwillingness of the Chinese government at the highest levels to take the actions necessary to reduce these rates, continues to be the cause of the greatest concern, particularly the failure to date to provide a truly deterrent enforcement system by imposing criminal penalties against pirates and by significantly increasing administrative fines for acts of piracy. Piracy by both unlicensed and licensed optical disc factories continues to flood the domestic market with pirate music, movies, videogames, books, and business software, making it very difficult for local Chinese creators and U.S. right holders to build viable businesses in China. Exports have diminished to a trickle, but pirate Chinese optical disc (OD) product has been found in Hong Kong, Russia and Vietnam. Piracy at the wholesale and retail level, and over the Internet, remains rampant, even though provincial and central government authorities, as well as Customs with respect to pirate imports, have undertaken numerous raids and massive seizures. The lack of deterrence in the system, the uncoordinated enforcement activities throughout China, the lack of transparency, and continued local protectionism are the primary causes of China’s inability to reduce piracy rates. -

Openbsd Gaming Resource

OPENBSD GAMING RESOURCE A continually updated resource for playing video games on OpenBSD. Mr. Satterly Updated August 7, 2021 P11U17A3B8 III Title: OpenBSD Gaming Resource Author: Mr. Satterly Publisher: Mr. Satterly Date: Updated August 7, 2021 Copyright: Creative Commons Zero 1.0 Universal Email: [email protected] Website: https://MrSatterly.com/ Contents 1 Introduction1 2 Ways to play the games2 2.1 Base system........................ 2 2.2 Ports/Editors........................ 3 2.3 Ports/Emulators...................... 3 Arcade emulation..................... 4 Computer emulation................... 4 Game console emulation................. 4 Operating system emulation .............. 7 2.4 Ports/Games........................ 8 Game engines....................... 8 Interactive fiction..................... 9 2.5 Ports/Math......................... 10 2.6 Ports/Net.......................... 10 2.7 Ports/Shells ........................ 12 2.8 Ports/WWW ........................ 12 3 Notable games 14 3.1 Free games ........................ 14 A-I.............................. 14 J-R.............................. 22 S-Z.............................. 26 3.2 Non-free games...................... 31 4 Getting the games 33 4.1 Games............................ 33 5 Former ways to play games 37 6 What next? 38 Appendices 39 A Clones, models, and variants 39 Index 51 IV 1 Introduction I use this document to help organize my thoughts, files, and links on how to play games on OpenBSD. It helps me to remember what I have gone through while finding new games. The biggest reason to read or at least skim this document is because how can you search for something you do not know exists? I will show you ways to play games, what free and non-free games are available, and give links to help you get started on downloading them. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

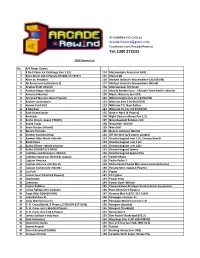

Arcade Rewind 3500 Games List 190818.Xlsx

ArcadeRewind.com.au [email protected] Facebook.com/ArcadeRewind Tel: 1300 272233 3500 Games List No. 3/4 Player Games 1 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 114 Metamorphic Force (ver EAA) 2 Alien Storm (US,3 Players,FD1094 317-0147) 115 Mexico 86 3 Alien vs. Predator 116 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (US,FD1094) 4 All American Football (rev E) 117 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (World) 5 Arabian Fight (World) 118 Minesweeper (4-Player) 6 Arabian Magic <World> 119 Muscle Bomber Duo - Ultimate Team Battle <World> 7 Armored Warriors 120 Mystic Warriors (ver EAA) 8 Armored Warriors (Euro Phoenix) 121 NBA Hangtime (rev L1.1 04/16/96) 9 Asylum <prototype> 122 NBA Jam (rev 3.01 04/07/93) 10 Atomic Punk (US) 123 NBA Jam T.E. Nani Edition 11 B.Rap Boys 124 NBA Jam TE (rev 4.0 03/23/94) 12 Back Street Soccer 125 Neck-n-Neck (4 Players) 13 Barricade 126 Night Slashers (Korea Rev 1.3) 14 Battle Circuit <Japan 970319> 127 Ninja Baseball Batman <US> 15 Battle Toads 128 Ninja Kids <World> 16 Beast Busters (World) 129 Nitro Ball 17 Blazing Tornado 130 Numan Athletics (World) 18 Bomber Lord (bootleg) 131 Off the Wall (2/3-player upright) 19 Bomber Man World <World> 132 Oriental Legend <ver.112, Chinese Board> 20 Brute Force 133 Oriental Legend <ver.112> 21 Bucky O'Hare <World version> 134 Oriental Legend <ver.126> 22 Bullet (FD1094 317-0041) 135 Oriental Legend Special 23 Cadillacs and Dinosaurs <World> 136 Oriental Legend Special Plus 24 Cadillacs Kyouryuu-Shinseiki <Japan> 137 Paddle Mania 25 Captain America 138 Pasha Pasha 2 26 Captain America -

Perspectives, Spring 2011 - Full Issue," Perspectives: Vol

Recommended Citation (2011) "Perspectives, Spring 2011 - Full Issue," Perspectives: Vol. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholars.unh.edu/perspectives/vol3/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals and Publications at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Perspectives by an authorized editor of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Perspectives Volume 3 Spring 2011 Article 1 5-2011 Perspectives, Spring 2011 - Full Issue Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/perspectives et al.: Perspectives, Spring 2011 - Full Issue Perspectives 2011 Table of Contents I. LAW AND POLITICS Jury Verdicts and Biases in the United States Valerie Barthell The Effects of the Characteristics of a Violent Crime and Its Offender on Recidivism Rates: A Literature Review Ashley Clark Do Race, Religion, or Gender Affect Death Penalty Support In the United States? Celie Morin Student Attitudes towards Male Inmate Sexual Violence: Gender Differences in Perceptions of Victimization Policy Bethany Schmidt Student Perspectives on Law Enforcement at UNH Victoria Vinciguerra and Dana Magane The Israel‐Palestine Problem: How Minimizing the Conflict Would Lower the Threat of Terrorism Against the U.S. Ashley Charron II. FAMILY AND PARENTING The Family’s Influence in Determining Adolescent Religiosity Ryan Rafford The Effects of Parenting Style on Adolescent Substance Use Samantha Story i Published by University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository, 2011 1 Perspectives, Vol. 3 [2011], Art. 1 III. ACADEMICS AND EDUCATION How Do Social and Economic Factors Affect Academic Achievement among Adolescent Students? An Observation of Community Social Capital, Peer Relationships, and Economic Composition Kendall Clark The Effect of Socioeconomic Status, Parental Involvement and Self Esteem on the Education of African Americans Kelby M. -

The Cultural Aspect of Video Game Regulation Practices

The Cultural Aspect of Video Game Regulation Practices «A comparative study of the differences in video game rating practices between Europe and Japan» Marita Eriksen Haugland Master’s thesis in Nordic Media Department of Media and Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Fall 2018 The Cultural Aspect of Video Game Regulation Practices «A comparative study of the differences in video game rating practices between Europe and Japan» Marita Eriksen Haugland Master’s thesis in Nordic Media II Department of Media and Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Fall 2018 III © Marita Eriksen Haugland 2018 The Cultural Aspect of Video Game Regulation Practices: A comparative study of the differences in video game rating practices between Europe and Japan Marita Eriksen Haugland http://www.duo.uio.no/ Print: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract Video games have become a large part of media consumption, both for adults and children. This study contributes to the field of children and media by looking into the perceptions and construction of risk by self-regulatory organizations, as well as into self-regulatory effectiveness. The thesis also discusses the struggle and the compromises between child safety, cultural differences and freedom of expression. It takes up the question of how the cultural differences affect the age ratings and content descriptors. All video games rated in Europe and Japan between 2010-2016 are analyzed to show the differences between the regions. Also, content analyses are performed on 24 video games with emblematic differences in age ratings or content descriptors. The findings suggest that cultural differences in how the two systems view crime, non-realistic violence, realistic blood, non-sexual nudity, romantic behavior, and sexualized behavior is responsible for some of the differences in age ratings and content descriptors. -

3500-Arcadegamelist.Pdf

No. GameName PlayersGroup 1 10 Yard Fight <Japan> Sport 2 1000 Miglia:Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) Driving 3 18 Challenge Pro Golf (DECO,Japan) Sport 4 18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) Sport 5 1941:Counter Attack (World 900227) Shoot 6 1942 (Revision B) Shoot 7 1943 Kai:Midway Kaisen (Japan) Shoot 8 1943:The Battle of Midway (Euro) Shoot 9 1944:The Loop Master (USA 000620) Shoot 10 1945k III (newer, OPCX2 PCB) Shoot 11 19XX:The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) Shoot 12 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge 3/4P Sport 13 2020 Super Baseball <set 1> Sport 14 3 Count Bout/Fire Suplex Fighter 15 3D_Aqua Rush (JP) Ver. A Maze 16 3D_Battle Arena Toshinden 2 Fighter 17 3D_Beastorizer (US) Fighter 18 3D_Beastorizer <US *bootleg*> Fighter 19 3D_Bloody Roar 2 <Japan> Fighter 20 3D_Brave Blade <Japan> Fighter 21 3D_Cool Boarders Arcade Jam (US) Sport 22 3D_Dancing Eyes <Japan ver.A> Adult 23 3D_Dead or Alive++ Fighter 24 3D_Ehrgeiz (US) Ver. A Fighter 25 3D_Fighters Impact A (JP 2.00J) Fighter 26 3D_Fighting Layer (JP) Ver.B Fighter 27 3D_Gallop Racer 3 (JP) Sport 28 3D_G-Darius (JP 2.01J) Sport 29 3D_G-Darius Ver.2 (JP 2.03J) Sport 30 3D_Heaven's Gate Fighter 31 3D_Justice Gakuen (JP 991117) Fighter 32 3D_Kikaioh (JP 980914) Fighter 33 3D_Kosodate Quiz My Angel 3 (JP) Ver.A Maze 34 3D_Magical Date EX (JP 2.01J) Maze 35 3D_Monster Farm Jump (JP) Maze 36 3D_Mr Driller (JP) Ver.A Maze 37 3D_Paca Paca Passion (JP) Ver.A Maze 38 3D_Plasma Sword (US 980316) Fighter 39 3D_Prime Goal EX (JP) Sport 40 3D_Psychic Force (JP 2.4J) Fighter 41 3D_Psychic Force (World 2.4O) Fighter 42 3D_Psychic Force EX (JP 2.0J) Fighter 43 3D_Raystorm (JP 2.05J) Shoot 44 3D_Raystorm (US 2.06A) Shoot 45 3D_Rival Schools (ASIA 971117) Fighter 46 3D_Rival Schools <US 971117> Fighter 47 3D_Shanghai Matekibuyuu (JP) Maze 48 3D_Sonic Wings Limited <Japan> Shoot 49 3D_Soul Edge (JP) SO3 Ver. -

Intellivision 20Th Birthday

Contact: Amelia Edgar/Jo Hunt FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DeLyon-Hunt & Associates 1444 Aviation Blvd., Suite 101 Redondo Beach, CA 90278 310/374-6893 [email protected] INTELLIVISION CELEBRATES ITS 20TH BIRTHDAY AT THE 2000 CLASSIC GAMING EXPO Join In the “Mature” Celebration of the Classic Console System and Games With Silly Antics, Party Hats, Cake and Noisemakers LAS VEGAS (July 29, 2000) – Bam! Ka-Pow! Boom! Whoosh! Whoosh? It’s not Batman reruns…It’s video game karaoke. Designed for those who cannot play a video game without humming – or booming or whizzing – along, video game karaoke allows the contestant to use his “noisemaker” to mimic or recreate the sound effects of a video game. Also for those who always thought they could do better than the often insipid noises games make, the karaoke contest is just part of the 20th birthday celebration that will take place in the Intellivision Productions booth at the Classic Gaming Expo in Las Vegas July 29-30. Intellivision Productions will hold several birthday-related events in its booth at the Expo, including the video game karaoke contest on Saturday the 29th at noon and a birthday cake cutting ceremony on Sunday the 30th at 3 p.m. In between, there will be games to play, prizes to win and the chance to speak with some of the people who designed the classic games you know and love, the Blue Sky Rangers. The Rangers will also serve as the panel of judges for the karaoke contest, and prizes will be awarded based on creativity. -

5794 Games.Numbers

Table 1 Nintendo Super Nintendo Sega Genesis/ Master System Entertainment Sega 32X (33 Sega SG-1000 (68 Entertainment TurboGrafx-16/PC MAME Arcade (2959 Games) Mega Drive (782 (281 Games) System/NES (791 Games) Games) System/SNES (786 Engine (94 Games) Games) Games) Games) After Burner Ace of Aces 3 Ninjas Kick Back 10-Yard Fight (USA, Complete ~ After 2020 Super 005 1942 1942 Bank Panic (Japan) Aero Blasters (USA) (Europe) (USA) Europe) Burner (Japan, Baseball (USA) USA) Action Fighter Amazing Spider- Black Onyx, The 3 Ninjas Kick Back 1000 Miglia: Great 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) 6-Pak (USA) 1942 (Japan, USA) Man, The - Web of Air Zonk (USA) 1 on 1 Government (Japan) (USA) 1000 Miles Rally (World, set 1) (v1.2) Fire (USA) 1941: Counter 1943 Kai: Midway Addams Family, 688 Attack Sub 1943 - The Battle of 7th Saga, The 18 Holes Pro Golf BC Racers (USA) Bomb Jack (Japan) Alien Crush (USA) Attack Kaisen The (Europe) (USA, Europe) Midway (USA) (USA) 90 Minutes - 1943: The Battle of 1944: The Loop 3 Ninjas Kick Back 3-D WorldRunner Borderline (Japan, 1943mii Aerial Assault (USA) Blackthorne (USA) European Prime Ballistix (USA) Midway Master (USA) (USA) Europe) Goal (Europe) 19XX: The War Brutal Unleashed - 2 On 2 Open Ice A.S.P. - Air Strike 1945k III Against Destiny After Burner (World) 6-Pak (USA) 720 Degrees (USA) Above the Claw Castle, The (Japan) Battle Royale (USA) Challenge Patrol (USA) (USA 951207) (USA) Chaotix ~ 688 Attack Sub Chack'n Pop Aaahh!!! Real Blazing Lazers 3 Count Bout / Fire 39 in 1 MAME Air Rescue (Europe) 8 Eyes (USA) Knuckles' Chaotix 2020 Super Baseball (USA, Europe) (Japan) Monsters (USA) (USA) Suplex bootleg (Japan, USA) Abadox - The Cyber Brawl ~ AAAHH!!! Real Champion Baseball ABC Monday Night 3ds 4 En Raya 4 Fun in 1 Aladdin (Europe) Deadly Inner War Cosmic Carnage Bloody Wolf (USA) Monsters (USA) (Japan) Football (USA) (USA) (Japan, USA) 64th. -

All Fun and (Mind) Games? Protecting Consumers

ALL FUN AND (MIND) GAMES? PROTECTING CONSUMERS FROM THE MANIPULATIVE HARMS OF INTERACTIVE VIRTUAL REALITY 2019 UILJLTP 299 | Yusef Al-Jarani | University of Illinois Journal of Law, Technology and Policy Document Details All Citations: 2019 U. Ill. J.L. Tech. & Pol'y 299 Search Details Jurisdiction: National Delivery Details Date: March 3, 2020 at 7:50 PM Delivered By: kiip kiip Client ID: KIIPIP Status Icons: © 2020 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. ALL FUN AND (MIND) GAMES? PROTECTING..., 2019 U. Ill. J.L. Tech.... 2019 U. Ill. J.L. Tech. & Pol'y 299 University of Illinois Journal of Law, Technology and Policy Fall, 2019 Article Yusef Al-Jarani d1 Copyright © 2019 by The Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois; Yusef Al-Jarani ALL FUN AND (MIND) GAMES? PROTECTING CONSUMERS FROM THE MANIPULATIVE HARMS OF INTERACTIVE VIRTUAL REALITY Abstract Information technologies increasingly influence our daily lives. While mostly benign, revolutionarily affective technologies are emerging that pose potential autonomy, economic, and privacy harms to consumers. Interactive virtual reality, or VR gaming, is arguably chief among them. But despite its rapid adoption by consumers (often for use by children) and its demonstrable power to manipulate human cognition and behavior, the law is ill-equipped to curtail its harms. This is owed to a general incognizance of the now-extensive research on the technology's manipulative effects and the consequent lack of discussion in public forums on how best to constrain them, both doctrinally and practically. This Article aims to enlighten lawmakers, jurists, and the general public about the effects of interactive VR, demonstrate how First Amendment doctrine permits the constraint of its manipulative harms, and illustrate what those constraints might look like in practice. -

Compatible Games List

MAME ARCADE GAMES LIST - 4600+ Non-duplicated ORIGINAL ROM/Code Arcade Games - Game Name (Alphabetic) 88 Games 99: The Last War 1 on 1 Government 10-Yard Fight '85 10-Yard Fight 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally 18 Challenge Pro Golf 18 Holes Pro Golf 1941: Counter Attack 1942 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen 1943: Battle of Midway 1943: Midway Kaisen 1943: The Battle of Midway 1944: The Loop Master 1945 Part-2 1945k III 1991 Spikes 19XX: The War Against Destiny 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge 2020 Super Baseball 280-ZZZAP 3 Bags Full 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex 3 On 3 Dunk Madness 3-D Bowling 30 Test 39 in 1 MAME bootleg 3X3 Puzzle 4 En Raya 4 Fun in 1 4-D Warriors 4nin-uchi Mahjong Jantotsu 64th. Street - A Detective Story 7 e Mezzo 7 Ordi 720 Degrees 7jigen no Youseitachi - Mahjong 7 Dimens... 800 Fathoms 9-Ball Shootout 9-Ball Shootout Championship A Question of Sport A. D. 2083 A.B. Cop Aaargh Abscam Abunai Houkago - Mou Matenai Ace Attacker Ace Driver: Racing Evolution Ace Driver: Victory Lap Acrobat Mission Acrobatic Dog-Fight Act Raiser Act-Fancer Cybernetick Hyper Weapon Action 2000 Action Fighter Action Hollywood Aero Fighters Aero Fighters 2 / Sonic Wings 2 Aero Fighters 3 / Sonic Wings 3 Aero Fighters Special Aeroboto MAME ARCADE GAMES LIST - 4600+ Non-duplicated ORIGINAL ROM/Code Arcade Games - Game Name (Alphabetic) Aerolitos After Burner After Burner II Age Of Heroes - Silkroad 2 Agent Super Bond Agent X Aggressors of Dark Kombat / Tsuukai GANG... Agress - Missile Daisenryaku Ah Eikou no Koshien Air Assault Air Attack Air Buster: Trouble Specialty Raid Unit Air Duel Air Gallet Air Race Air Rescue Airwolf Ajax Akkanbeder Akuma-Jou Dracula Akuu Gallet Aladdin Alcon Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars Ali Baba and 40 Thieves Alien Arena Alien Challenge Alien Crush Alien Invaders Alien Invasion Alien Invasion Part II Alien Sector Alien Storm Alien Syndrome Alien vs. -

4539-Arcadegamelist.Pdf

1 005 80 3D_Tekken (WORLD) Ver. B 157 Alien Storm (Japan, 2 Players) 2 1 on 1 Government (Japan) 81 3D_Tekken <World ver.c> 158 Alien Storm (US,3 Players) 3 10 Yard Fight <Japan> 82 3D_Tekken 2 (JP) Ver. B 159 Alien Storm (World, 2 Players) 4 1000 Miglia:Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 83 3D_Tekken 2 (World) Ver. A 160 Alien Syndrome 5 10-Yard Fight ‘85 (US, Taito license) 84 3D_Tekken 2 <World ver.b> 161 Alien Syndrome (set 6, Japan, new) 6 18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 85 3D_Tekken 3 (JP) Ver. A 162 Alien vs. Predator (Euro 940520 Phoenix Edition) 7 1941: Counter Attack (USA 900227) 86 3D_Tetris The Grand Master 163 Alien vs. Predator (Euro 940520) 8 1941:Counter Attack (World 900227) 87 3D_Tondemo Crisis 164 Alien vs. Predator (Hispanic 940520) 9 1942 (Revision B) 88 3D_Toshinden 2 165 Alien vs. Predator (Japan 940520) 10 1942 (Tecfri PCB, bootleg?) 89 3D_Xevious 3D/G (JP) Ver. A 166 Alien vs. Predator (USA 940520) 11 1943 Kai:Midway Kaisen (Japan) 90 3X3 Maze (Enterprise) 167 Alien3: The Gun (World) 12 1943: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 91 3X3 Maze (Normal) 168 Aliens <Japan> 13 1943:The Battle of Midway (Euro) 92 4 En Raya 169 Aliens <US> 14 1944: The Loop Master (USA Phoenix Edition) 93 4 Fun in 1 170 Aliens <World set 1> 15 1944:The Loop Master (USA 000620) 94 4-D Warriors 171 Aliens <World set 2> 16 1945 Part-2 (Chinese hack of Battle Garegga) 95 600 172 All American Football (rev D, 2 Players) 17 1945k III (newer, OPCX2 PCB) 96 64th.