The Best of Colin Wilson Ebook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECOMYSTICISM: MATERIALISM and MYSTICISM in AMERICAN NATURE WRITING by DAVID TAGNANI a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfill

ECOMYSTICISM: MATERIALISM AND MYSTICISM IN AMERICAN NATURE WRITING By DAVID TAGNANI A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of English MAY 2015 © Copyright by DAVID TAGNANI, 2015 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by DAVID TAGNANI, 2015 All Rights Reserved ii To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of DAVID TAGNANI find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________________ Christopher Arigo, Ph.D., Chair ___________________________________________ Donna Campbell, Ph.D. ___________________________________________ Jon Hegglund, Ph.D. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank my committee members for their hard work guiding and encouraging this project. Chris Arigo’s passion for the subject and familiarity with arcane source material were invaluable in pushing me forward. Donna Campbell’s challenging questions and encyclopedic knowledge helped shore up weak points throughout. Jon Hegglund has my gratitude for agreeing to join this committee at the last minute. Former committee member Augusta Rohrbach also deserves acknowledgement, as her hard work led to significant restructuring and important theoretical insights. Finally, this project would have been impossible without my wife Angela, who worked hard to ensure I had the time and space to complete this project. iv ECOMYSTICISM: MATERIALISM AND MYSTICISM IN AMERICAN NATURE WRITING Abstract by David Tagnani, Ph.D. Washington State University May 2015 Chair: Christopher Arigo This dissertation investigates the ways in which a theory of material mysticism can help us understand and synthesize two important trends in the American nature writing—mysticism and materialism. -

February 7–9, 14–16, 2020 Loft Stage at East Ridge High School MERRILL ARTS CENTER

MERRILL ARTS CENTER present a WCT production of Directed By Tom Reed February 7–9, 14–16, 2020 Loft Stage at East Ridge High School MERRILL ARTS CENTER a WCT production of WCT Production Staff Director Tom Reed so let chuck eckberg Music Director Jessie Rolfe help you find your Production Manager Leah Madsen Stage Manager MJ Luna Sound Designer Evangeline Lee dream castle! Props Designer Sarah Herman Scenic Designer Craig Steineck Costume Designer Bailey Remmers Lighting Designer Jacob Berg Even if the house isn’t in Transylvania, Choreographer Megan Torbert Chuck will electrify your journey and make sure you find MAC Administrative Staff “the happiest town” for you! Executive Director Barbe Marshall Hansen Managing Director Kajsa Jones SOS Director Kristin Fox Administrator Hannah Amidon See what a 14-time Super Real Estate AgentTM Accountant Irina Yaritz can do for you! Graphic Designer Galen Higgins Group Sales Director Alicia Wiesneth 604 Bielenberg Drive, Woodbury, MN 55125 651-246-6639 • [email protected] Publicists JAMU Enterprises www.chuckeckberg.com Director of Development Lori Nelson Digital Strategist Cromie Creative Consultants Box Office Managers Erika James, Jeriann Jones Lisa Winston MERRILL ARTS CENTER WANTED The Mission of Merrill Arts Center EMPLOYEE ENDORSEMENTS! is to champion the arts. PROGRAMS Do you work for one of these companies? Wells Fargo • Andersen Corporation • Otto Bremer Trust • Bremer Bank WCT McKnight Foundation • 3M • General Mills • Best Buy • Ecolab If yes, please let us know! AFFILIATES These companies, and many like them, have grant programs available to arts organizations like Merrill but we need an employee endorsement to apply. -

{PDF EPUB} Introduction to the New Existentialism by Colin Wilson the NEW EXISTENTIALISM

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Introduction to the New Existentialism by Colin Wilson THE NEW EXISTENTIALISM. “It is extremely important to grasp the notion that man does not yet exist. This is not intended as a paradox or a play on words; it is literally true.” Colin Wilson, Introduction to The New Existentialism. Given the name, the new existentialism and its revolutionary philosophical proposition might seem to suggest a summary or synthesis of the premises known to us as existentialist philosophy. Nothing could be further from the truth. If the new existentialism is the heir to any philosophy, it is Romanticism. Each shares a boldness and creative impulse, as well as an impassioned dream of immortality and desire to be on an equal footing with the gods. The new existentialism has more in common with Nietzsche and Goethe than with Sartre or Camus. The shift in consciousness and the new ideal of man forged by the Romantics find unparalleled and vital expression in the new existentialism. They were the first to speak of the unconscious and its inherent power, and to reclaim certain concepts and beliefs generally held to have become obsolete. And like Colin Wilson, they did so with unprecedented enthusiasm and verve, recognizing that the last word had not been said as regards man. Romantics upheld the central importance of man in the cosmos; the existentialists saw man as contingent. Romantics made the infinite mystery that surrounds us the basis of their enquiries and everything they went on to create, and, compelled by its heroic spirit, they viewed this mystery not as an affront but as proof of the existence of the sacred and of God; existentialists renounced imagination and its creative power and sought refuge in the narrow limitations of daily life with all its many trifles, thereby losing sight of the majestic and with it the idea of God and transcendence. -

Young Frankenstein"

"YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN" SCREENPLAY by GENE WILDER FIRST DRAFT FADE IN: EXT. FRANKENSTEIN CASTLE A BOLT OF LIGHTNING! A CRACK OF THUNDER! On a distant, rainy hill, the old Frankenstein castle, as we knew and loved it, is illuminated by ANOTHER BOLT OF LIGHTNING. MUSIC: AN EERIE TRANSYLVANIAN LULLABY begins to PLAY in the b.g. as we MOVE SLOWLY CLOSER to the castle. It is completely dark, except for one room -- a study in the corner of the castle -- which is only lit by candles. Now we are just outside a rain-splattered window of the study. We LOOK IN and SEE: INT. STUDY - NIGHT An open coffin rests on a table we can not see it's contents. As the CAMERA SLOWLY CIRCLES the coffin for a BETTER VIEW... A CLOCK BEGINS TO CHIME: "ONE," "TWO," "THREE," "FOUR..." We are ALMOST FACING the front of the coffin. "FIVE," "SIX," "SEVEN," "EIGHT..." The CAMERA STOPS. Now it MOVES UP AND ABOVE the satin-lined coffin. "NINE," "TEN," "ELEVEN," "T W E L V E!" CUT TO: THE EMBALMED HEAD OF BEAUFORT FRANKENSTEIN Half of still clings to the waxen balm; the other half has decayed to skull. Below his head is a skeleton, whose bony fingers cling to a metal box. A HAND reaches in to grasp the metal box. It lifts the box halfway out of the coffin -- the skeleton's fingers rising, involuntarily, with the box. Then, as of by force of will, the skeleton's fingers grab the box back and place it where it was. Now the "Hand" -- using its other hand -- grabs the box back from the skeleton's fingers. -

Existentialism and Ecstasy: Colin Wilson on the Phenomenology of Peak Experiences

PhænEx 13, no. 1 (Spring 2019): 46-85 © 2019 Biagio Gerard Tassone Existentialism and Ecstasy: Colin Wilson on the Phenomenology of Peak Experiences BIAGIO GERARD TASSONE Abstract This paper critically examines the philosophical foundations of Colin Wilson’s New Existentialism. I will show how Wilson’s writings promoted a phenomenological strategy for understanding states of ecstatic affirmation within so-called ‘peak experiences’. Wilson subsequently attempted to use the life affirming insights bestowed by peak states to establish an ontological ground for values to serve as a foundation for his New Existentialism. Because of its psychological focus however, I argue that Wilson’s New Existentialism contains an ambivalent framework for establishing ontological categories, which leads his thought into theoretical difficulties. More precisely, Wilson’s strategy runs into problems in coherently integrating its explicitly psychological interpretation of Husserl’s theory of intentionality within a broader, and philosophically coherent, phenomenological framework. Wilson’s psychological reading of Husserl’s transcendental reduction, for example, manifests tensions in how it reconciles the empirical basis of acts of transcendence with an essentialist conception of the self as a transcendental ego. The above tensions, I argue, ultimately render the New Existentialism susceptible to criticism from a Husserlian-transcendental perspective. After outlining a Husserlian critique of Wilson’s position, I end the paper by suggesting how some of the central -

Frankenstein: Or the Modern Prometheus Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FRANKENSTEIN: OR THE MODERN PROMETHEUS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley | 240 pages | 29 Jun 2011 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099512042 | English | London, United Kingdom Frankenstein: Or the Modern Prometheus PDF Book Retrieved 30 July Florescu, Radu Milner, Andrew. Archived from the original on 8 November During the two years that had elapsed previous to their marriage my father had gradually relinquished all his public functions; and immediately after their union they sought the pleasant climate of Italy, and the change of scene and interest attendant on a tour through that land of wonders, as a restorative for her weakened frame. Other motives were mingled with these, as the work proceeded. The Quarterly Review. Important Quotations Explained. In Shelley's original work, Victor Frankenstein discovers a previously unknown but elemental principle of life, and that insight allows him to develop a method to imbue vitality into inanimate matter, though the exact nature of the process is left largely ambiguous. SUNY Press. Day supports Florescu's position that Mary Shelley knew of, and visited Frankenstein Castle before writing her debut novel. Retrieved 19 September Retrieved 13 April Archived from the original on 13 February To watch the show, RSVP at www. She was not her child, but the daughter of a Milanese nobleman. These visions faded when I perused, for the first time, those poets whose effusions entranced my soul, and lifted it to heaven. American Film Institute. Mary Shelley in Her Times. He is an Englishman, and in the midst of national and professional prejudices, unsoftened by cultivation, retains some of the noblest endowments of humanity. -

Books and Coffee Past Presenters

Books and Coffee Past Presenters Year Speaker Author Title 1951 William Braswell Hemingway Across the River and Into the Trees Chester Eisinger Miller Death of a Salesman Paul Fatout -- “Mark Twain” Robert Lowe Pound Letters Barriss Mills Faulkner Collected Stories Herbert Muller Niebuhr Faith in History Albert Rolfs Fatout Ambrose Bierce Louise Rorabacher Orwell Animal Farm Emerson Sutcliffe Kent Declensions in the Air 1952 Welsey Carroll Boswell London Journal Richard Voorhees Greene The Power and the Glory Richard Cordell Irvine The Universe of George Bernard Shaw Harold Watts Mann The Holy Sinner Roy Curtis Hall Leave Your Language Alone! Richard Greene Altick The Scholar Adventurers R. W. Babcock -- “On Reading Shakespeare” Richard Crowder Williams Later Collected Poems 1953 Herbert Muller Ceram Gods, Graves, and Scholars William Hastings Wouk The Cain Mutiny J. H. McKee Ferril I Hate Thursday Arthur Koenig Dostoievsky The Diary of a Writer George Schick Boswell Boswell in Holland Darrel Abel Steinbeck East of Eden H. B. Knoll Walton The Compleat Angler Raymond Himelick Cabell Quiet Please 1954 Paul Fatout Boswell Boswell on the Grand Tour George S. Wykoff Bonavia-Hunt Pemberley Shades Lewis Freed Eliot The Cocktail Party R. M. Bertram Cary The Horse's Mouth Laird Bell Smith Man and His Gods Bernard Schmidt Michener The Bridges at Toki-Ri Victor Gibbens Randolf & Wilson Down in the Holler William Braswell Thurber Thurber Country 1955 Richard Cordell Larson An American in Europe Arnold Drew Jarrell Pictures from an Institution Russell Cosper Kafka The Castle M. W. Tillson Ives Tales of America Maurice Beebe Faulkner A Fable Walter Maneikis Algren The Man with the Golden Arm Virgil Lokke West The Day of the Locusts Robert Ogle White The Second Tree from the Corner 1956 Lewis Freed Alberto Moravia A Ghost at Noon R.W. -

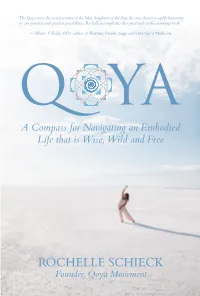

ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’S QOYA: a Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life That Is Wise, Wild and Free

“The Qoya were the sacred women of the Inka, daughters of the Sun, the ones chosen to uplift humanity to our grandest and greatest possibilities. Rochelle accomplishes this great task in this stunning book.” —Alberto Villoldo, PhD, author of Shaman, Healer, Sage and One Spirit Medicine Q YA A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’s QOYA: A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free “Through the sincere, witty, and profound sharing of her own life experiences, Rochelle reveals to us a valuable map to recover one’s joy, confidence, and authenticity. She shows us the way back to love by feeling gratitude for one’s own experiences. She offers us price- less tools and practices to reconnect with our innate intelligence and sense of knowing what is right for us. More than a book, this is a companion through difficult moments or for getting from well to wonderful!” —Marcela Lobos, shamanic healer, senior staff member at the Four Winds Society, and co-founder of Los Cuatro Caminos in Chile “Qoya represents the future – the future of spirituality, femininity, and movement. If I’ve learned anything in my work, it is that there is an awakening of women everywhere. The world is yearning for the balance of the feminine essence. This book shows us how to take the next step.” —Kassidy Brown, co-founder of We Are the XX “Rochelle Schieck has made her life into a solitary vow: to remem- ber who she is – not in thought or theory – but in her bones, in the truth that only exists in her body. -

The Secret Science Behind Miracles

THE SECRET SCIENCE BEHIND MIRACLES By Max Freedom Long Bird Publisher, 2010 CONTENTS 1. The Dicsivery that may chabge the World ________________________________________________ 4 2. Fire-walking as an introduction to Magic _______________________________________________ 14 3. The incredible force used in Magic, where it comes from, and some of its uses ______________ 27 4. The two Souls of Man and the proofs that there are two instead of one _____________________ 35 5. The Kahuna system and the three »Souls« or Spirits of Man, each using its own voltage of Vital Force. These Pririts in union and in separation ___________________________________ 43 6. Taking the Measure of the Third Element in Magic, that of the invisible substance through which consciousness acts by means of Force _____________________________________________ 51 7. Psychometry, crystal gazing, visions of the past, visions of the future, etc., explained by the Ancient Lore of the Kahumas __________________________________________________________ 55 8. Mind Reading, Clairvoyance, Visions, Previsions, Chrystal Gazing, and all ot the psychometrically related phenomena, as explained in Terms of the Ten Elements of the Ancient Huna System _________________________________________________________________ 59 9. The significance of seeing into the future in the psychometric phenomena and dreams _______ 67 10. The easy way to dream into the future _________________________________________________ 72 11. Instant Healing through the High Self. The proofs and methods __________________________ 79 12. Raising the dead, permenantly and temporarily _________________________________________ 83 13. The life-Giving secrets of Lomilomi and Laying of Hands _______________________________ 92 14. Starling new and different ideas from the Kahunas concerning the Nature of the Complex and Healing ________________________________________________________________ 99 15. The Secret Kahuna method of treating the Complex ____________________________________ 105 16. -

Dancing Into the Chthulucene: Sensuous Ecological Activism In

Dancing into the Chthulucene: Sensuous Ecological Activism in the 21st Century Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kelly Perl Klein Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Dr. Harmony Bench, Advisor Dr. Ann Cooper Albright Dr. Hannah Kosstrin Dr. Mytheli Sreenivas Copyrighted by Kelly Perl Klein 2019 2 Abstract This dissertation centers sensuous movement-based performance and practice as particularly powerful modes of activism toward sustainability and multi-species justice in the early decades of the 21st century. Proposing a model of “sensuous ecological activism,” the author elucidates the sensual components of feminist philosopher and biologist Donna Haraway’s (2016) concept of the Chthulucene, articulating how sensuous movement performance and practice interpellate Chthonic subjectivities. The dissertation explores the possibilities and limits of performances of vulnerability, experiences of interconnection, practices of sensitization, and embodied practices of radical inclusion as forms of activism in the context of contemporary neoliberal capitalism and competitive individualism. Two theatrical dance works and two communities of practice from India and the US are considered in relationship to neoliberal shifts in global economic policy that began in the late 1970s. The author analyzes the dance work The Dammed (2013) by the Darpana Academy for Performing Arts in Ahmedabad, -

Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs Vol.4: S - Z

Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs vol.4: S - Z © Neuss / Germany: Bruno Buike 2017 Buike Music and Science [email protected] BBWV E30 Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs - vol.4: S - Z Neuss: Bruno Buike 2017 CONTENT Vol. 1 A-D 273 p. Vol. 2 E-K 271 p. Vol. 3 L-R 263 p. Vol. 4 S-Z 239 p. Appr. 21.000 title entries - total 1046 p. ---xxx--- 1. Dies ist ein wissenschaftliches Projekt ohne kommerzielle Interessen. 2. Wer finanzielle Forderungen gegen dieses Projekt erhebt, dessen Beitrag und Name werden in der nächsten Auflage gelöscht. 3. Das Projekt wurde gefördert von der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Sozialamt Neuss. 4. Rechtschreibfehler zu unterlassen, konnte ich meinem Computer trotz jahrelanger Versuche nicht beibringen. Im Gegenteil: Das Biest fügt immer wieder neue Fehler ein, wo vorher keine waren! 1. This is a scientific project without commercial interests, that is not in bookstores, but free in Internet. 2. Financial and legal claims against this project, will result in the contribution and the name of contributor in the next edition canceled. 3. This project has been sponsored by the Federal Republic of Germany, Department for Social Benefits, city of Neuss. 4. Correct spelling and orthography is subject of a constant fight between me and my computer – AND THE SOFTWARE in use – and normally the other side is the winning party! Editor`s note – Vorwort des Herausgebers preface 1 ENGLISH SHORT PREFACE „Paul Smith“ is a FAKE-IDENTY behind which very probably is a COLLCETIVE of writers and researchers, using a more RATIONAL and SOBER approach towards the complex of Rennes-le-Chateau and to related complex of „Priory of Sion“ (Prieure de Sion of Pierre Plantard, Geradrd de Sede, Phlippe de Cherisey, Jean-Luc Chaumeil and others). -

Mana for a New Age Rachel Morgain

11 Mana for a New Age Rachel Morgain From chakra healing to African drumming, sweat lodges to shamanic journeys, New Age movements, particularly in North America, are notorious for their pattern of appropriating concepts and practices from other spiritual traditions. While continental Native American and Asian influences are perhaps most familiar as sourcing grounds for New Age material, the traditions of Pacific Islanders, particularly Hawaiians, have not escaped New Age attention. In particular, the movement known as ‘Huna’ has introduced Hawaiian-sounding words and concepts to the New Age vocabulary. Chief among these is the concept of ‘mana’, controversially subsumed within what is often a large laundry list of non-western religious and philosophical nomenclature, under the generic category of ‘energy’ or ‘life force’. Continually adapted through succeeding generations of Huna teachings, and further adopted into sections of the related contemporary Pagan movement through the tradition known as ‘Feri’, the concept of ‘mana’ displays some consistent themes across these traditions, quite different from its meaning in Hawaiian contexts. In being adopted into these movements, it has been transformed to fit within a field of ideas that have developed in western esoteric traditions from at least the late eighteenth century. In this chapter, I trace some of the ideas that have come to be attached to the concept of mana through several iterations of New Age movements in North America. Beginning with the foundational 285 NEW MANA works of Max Freedom Long, I look at the spiritual practice known as Huna, popularised from the late 1930s through a series of Long’s texts and his Huna Research organisation.