UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iraq Missile Chronology

Iraq Missile Chronology 2008-2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003-2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 1998 | 1997 | 1996 | 1995 | 1994 | 1993 | 1992 | 1991 Last update: November 2008 As of November 2008, this chronology is no longer being updated. For current developments, please see the Iraq Missile Overview. 2008-2006 29 February 2008 UNMOVIC is officially closed down as directed by UN Security Council Resolution 1762, which terminated its mandate. [Note: See NTI Chronology 29 June 2007]. —UN Security Council, "Iraq (UNMOVIC)," Security Council Report, Update Report No. 10, 26 June 2008. 25 September 2007 U.S. spokesman Rear Admiral Mark Fox claims that Iranian-supplied surface-to-air missiles, such as the Misagh 1, have been found in Iraq. The U.S. military says that these missiles have been smuggled into Iraq from Iran. Iran denies the allegation. [Note: See NTI Chronology 11 and 12 February 2007]. "Tehran blasted on Iraq Missiles," Hobart Mercury, 25 September 2007, in Lexis-Nexis Academic Universe; David C Isby, "U.S. Outlines Iranian Cross-Border Supply of Rockets and Missiles to Iraq," Jane's Missiles & Rockets, Jane's Information Group, 1 November 2007. 29 June 2007 The Security Council passes Resolution 1762 terminating the mandates of the UN Monitoring, Verification, and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) and the IAEA in Iraq. Resolution 1762 also requests the UN Secretary General to dispose safely of archives containing sensitive information, and to transfer any remaining UNMOVIC funds to the Development Fund for Iraq. A letter to the Security Council from the Iraqi government indicates it is committed to respecting its obligations to the nonproliferation regime. -

The Defense Industry of Brazil Contents

Chapter 9 The Defense Industry of Brazil Contents PRODUCTION FOR EXPORT . 143 AIRCRAFT’ . 143 COLLABORATIVE PROGRAMS . 147 ARMORED VEHICLES.... 148 MISSILES . 149 ORBITA . 150 CONCLUSION . ..*,.*.. ,...,.. 150 Figure Page 9-1. Brazilian Exports,1965-88 . 146 Table Table Page 9-1.Brazilian Exports, 1977-88 . .. 144 Chapter 9 The Defense Industry of Brazil PRODUCTION FOR EXPORT expenditures over the past 20 years have been relatively insignificant, averaging 1.3 percent of Brazil emerged in the mid-1980s as the leading gross domestic product per year (see figure 9-l). As arms producer and exporter among the defense a result, the government has used various fiscal industrializing countries, and the sixth largest arms incentives and trade policies to promote an eco- exporter in the world. The Iran-Iraq War, in particu- nomic environment in which these firms may lar, stimulated arms exports by Brazilian defense operate.3 The most direct form of government companies. Iraq has been Brazil’s largest customer, support is to encourage linkage between the research purchasing armored personnel carriers, missiles, and institutes of the armed forces and the respective aircraft, often in exchange for oil (see table 9-l). industries: the Aerospace Technical Center (CTA) for the aircraft and missile-related companies, the The termination of hostilities between the two Army Technical Center (CTE ) for the armored Persian Gulf rivals in 1988 has had a debilitating X vehicle industries, and the Naval Research Center effect on two Brazilian companies, Avibras and l (CPqM) for the naval sector. Engesa. Both companies are in financial crisis, despite the conclusion in 1988 of a major arms deal In contrast to other developing nations, state with Libya. -

The Revista Aérea Collection

The Revista Aérea Collection Dan Hagedorn and Pedro Turina 2008 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series A: Aircraft...................................................................................................... 4 Series B: Propulsion............................................................................................. 218 Series C: Biography............................................................................................. 262 Series D: Organizations...................................................................................... -

Production D'armement: Le Brésil En Quête D'autonomie

N° 02/2015 recherches & documents juin 2015 Production d’armement : le Brésil en quête d’autonomie HÉLÈNE MASSON, EDUARDO SIQUEIRA BRICK, KÉVIN MARTIN WWW. FRSTRATEGIE. ORG Ce Recherches&Documents n°2/2015 représente le Volume 1 et la partie introductive du Volume 2, extraits du rapport Etude et évolution de la base industrielle et technologique de défense (BITD) du Brésil, EPS 2012-29, août 2014. Rapport en 4 volumes : Vol.1. BITD et politiques publiques, 123 pages (Hélène Masson, Eduardo Siqueira Brick) ; Vol.2. BITD brésilienne : analyse sectorielle et monographies, 307 pages (Kevin Martin, Hélène Masson, Patrick van den Ende) ; Vol.3. L'industrie spatiale au Brésil, 41 pages (Florence Gaillard-Sborowsky) ; Vol.4. Analyse de O¶LQIRUPDWLRQVFLHQWLILTXHHWWHFKQLTXHGHOD%,7'EUpVilienne, 92 pages (TKM). Le Volume 4 est disponible sur le site de la FRS. Edition juin 2015 Manuscrit achevé en août 2014 Édité et diffusé par la Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique 4 bis rue des Pâtures ± 75016 PARIS ISSN : 1966-5156 ISBN : 978-2-911101-83-0 EAN : 9782911101830 WWW.FRSTRATEGIE.ORG 4 BIS RUE DES PÂTURES 75016 PARIS TÉL.01 43 13 77 77 FAX 01 43 13 77 78 SIRET 394 095 533 00052 TVA FR74 394 095 533 CODE APE 7220Z FONDATION RECONNUE D'UTILITÉ PUBLIQUE ± DÉCRET DU 26 FÉVRIER 1993 Table des matières Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Industries de défense et politiques publiques au Brésil ............................................ 7 -

BRAZIL, the UNITED STATES, and the MISSILE TECHNOLOGY CONTROL REGIME (Unclassified)

LIBRARY NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CftUFORWA 93340 I NPS- 5 6-90-006 T$ NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California BRAZIL, THE UNITED STATES, AND i THE MISSILE TECHNOLOGY CONTROL REGIME by SCOTT D. TOLLEFSON Approved for public release; distribution unlimited Prepared for: Naval Postgraduate School Monterey, CA 93943-5100 FEDDOCS D 208. 14/2 NPS-56-90-006 FeddtotA -WS^, (4 Cl NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA Rear Admiral Ralph W. West, Jr. Harrison Shull Provost Superintendent , This report was prepared in conjunction with research funded by the Naval Postgraduate School Research Council. Reproduction of all or part of this report is authorized. This report was edited by: inUlVlAS <^. BKUfNfcAU liUKDUIN SCHACHEK Chairman Dean of Faculty and Department of National Graduate Studies Security Affairs DUDLEY KNOX LIBRARY NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY CA 93943-5101 . H ">£ K ir ^If^f^^ TTaST REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE \i REPORT SECURITY CLASSIFICATION lb RESTRICTIVE MARKINGS "NriASSTFTFR 2i security Classification authority 3 DISTRIBUTION/ AVAILABILITY OP REPORT APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Zb DECLASSIFICATION/ DOWNGRADING SCHEDULE UNLIMITED DISTRIBUTION 4 PERFORMING ORGANISATION REPORT NUM8£R(S) S MONITORING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBEfl(S) NPS - 56 - 90 - 006 ' 6d NAME OF PERFORMING ORGANIZATION 60 OFFICE SYMBOL 73 NAME OF MONITORING ORGANIZATION (if tpphctble) Naval Postgraduate School 56 6< ADDRESS (Cry Sf3f* *nd HP Code) 7b ADDRESS (City. Sure. »nd HP Code) NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL DEPT. OF NATIONAL SECURITY AFFAIRS MONTEREY^ CA 93943-5100 8a NAME OF FUNDING /SPONSORING 8b OFFICE SYMBOL 9 PROCUREMENT INSTRUMENT IOEN Tif iCATlON NUMBER ORGANIZATION (If ippliabit) Research Council O&MN, Direct Funding 3c AOORESSK<ry. Stite ind ZlPCode) io source of funding numbers PROGRAM PROJECT TAS< WORK JNIT NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL ELEMENT NO NO NO ACCESSION NO MONTEREY, CA 93943-5100 1 T.TlE (includt Security CUuifiation) BRAZIL, THE UNITED STATES, AND THE MISSILE TECHNOLOGY CONTROL REGIME (Unclassified) PERSONA L AuThOR(S) SCOTT D. -

Global Arms Trade: Commerce in Advanced Military Technology and Weapons

Global Arms Trade: Commerce in Advanced Military Technology and Weapons June 1991 OTA-ISC-460 NTIS order #PB91-212175 GPO stock #052-003-01244-8 Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Global Arms Trade, OTA-ISC-460 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, June 1991). For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402-9325 (order form can be found in the back of this report) ii Foreword The recent war in the Persian Gulf has once again focused attention on the proliferation of advanced weapons and the international arms industry. Although Iraq had little or no defense industrial capability, it was able to obtain a vast arsenal of modern weapons from the Soviet Union, Western Europe, China, Eastern Europe, and a variety of arms producers in the developing world. Today, the international arms market is a buyers’ market in which modern tanks, fighter aircraft, submarines, missiles, and other weapons are available to any nation that can afford them. Increasingly, sales of major weapons also include the transfer of the underlying technologies necessary for local production, resulting in widespread proliferation of modern weapons and the means to produce--and even develop--them. The end of the Cold War has brought profoundly decreased demand for weapons by the United States, the Soviet Union, and most European governments. In the United States, and elsewhere, some defense companies are seeking to increase their international sales as part of a strategy to adjust to the new realities of lower procurement budgets and less domestic demand for their products. -

Guns, Engines and Turbines. the Eu's Hard Power in Asia, ISS Chaillot Papers, November 2018, Chapter

CHAILLOT PAPER Nº 149 — November 2018 Guns, engines and turbines The EU’s hard power in Asia EDITED BY Eva Pejsova WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM Mathieu Duchâtel, Felix Heiduk, Bruno Hellendorff, Chantal Lavallée, Liselotte Odgaard, Gareth Price and Zoe Stanley-Lockman Chaillot Papers European Union Institute for Security Studies 100, avenue de Suffren 75015 Paris http://www.iss.europa.eu Director: Gustav Lindstrom © EU Institute for Security Studies, 2018. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. print ISBN 978-92-9198-766-5 online ISBN 978-92-9198-765-8 ISSN 1017-7566 ISSN 1683-4917 QN-AA-18-006-EN-C QN-AA-18-006-EN-N DOI:10.2815/988862 DOI:10.2815/6415 Published by the EU Institute for Security Studies and printed in Belgium by Bietlot. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2018. Cover image credit: LittleVisuals/pixabay GUNS, ENGINES AND TURBINES THE EU’S HARD POWER IN ASIA Edited by Eva Pejsova CHAILLOT PAPERS November 2018 149 Acknowledgements The contributions to this Chaillot Paper are inspired by presentations and discussions at the 5th annual meeting of the European Member Committee of the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific (CSCAP EU), which took place on 18-19 January 2018 in Brussels. The editor would like to thank the authors of the various chapters of this volume, as well as all CSCAP EU Committee members who took part in the meeting and contributed to the deliberations. Special thanks go to Mathieu Duchâtel and Felix Heiduk for their initial input and expertise on the subject matter, Alexander McLachlan for his insights on the EU’s official position and policies and Natalia Martin for her assiduous work on data collection and editorial assistance. -

A Global Overview of Explosive Submunitions 1 May 2002 System

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH 1630 Connecticut Ave. NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 Telephone: 202-612-4321 Facsimile: 202-612-4333 E-mail: [email protected] HUMAN Website:http://www.hrw.org RIGHTS ARMS DIVISION Joost R. Hiltermann WATCH Executi ve Director Stephen D. Goose Program Director William M. Arkin Senior Military Advisor Mary Wareham Senior Advocate Mark Hiznay Alex Vines Senior Researchers Reuben E. Brigety, II Lisa Misol Researchers Bonnie Docherty Fellow Hannah Novak Charli Wyatt Asso ciates Monica Schurtman Consultant ADVISORY COMMITTEE David Brown Vincent McGee HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Co -Chairs Nicole Ball Vice Chair Ahmedou Ould Abdallah MEMORANDUM TO CCW DELEGATES Ken Anderson Rony Brauman Ahmed H. Esa Steve Fetter A GLOBAL OVERVIEW OF William Hartung Alastair Hay Eboe Hutchful EXPLOSIVE SUBMUNITIONS Patricia Irvin Michael Klare Frederick J. Knecht Edward J. Laurance Prepared for the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) Group of Governmental Graca Machel Janne E. Nolan Andrew J. Pierre Experts on the Explosive Remnants of War (ERW) Eugenia Piza - Lopez David Rieff Julian Perry Robinson John Ryle May 21-24, 2002 Mohamed Sahnoun Desmond Tutu Torsten N. Wiesel Jody Williams HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Kenneth Roth Executive Director Michele Alexander Development and Outreach Director Introduction ............................................................................................1 Carroll Bogert Communications Director A Prevalence of Submunitions ...............................................................1 John T. Green Operations -

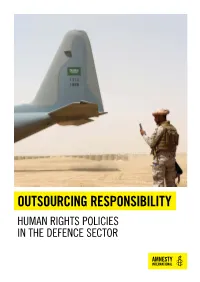

Outsourcing Responsibility

OUTSOURCING RESPONSIBILITY HUMAN RIGHTS POLICIES IN THE DEFENCE SECTOR Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2019 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, Cover photo: A soldier stands guard before a Royal Saudi Air Force cargo international 4.0) licence. plane at an airfield in Yemen's central Marib province, 12 March 2018, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © ABDULLAH AL-QADRY/AFP/Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2019 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ACT 30/0893/2019 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS GLOSSARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY METHODOLOGY 1. BACKGROUND 8 1.1 THE DEFENCE INDUSTRY 8 1.2 STATE REGULATION OF THE ARMS TRADE 11 1.3 HUMAN RIGHTS RISKS FACED BY THE DEFENCE INDUSTRY 12 2. THE HUMAN RIGHTS RESPONSIBILITIES OF COMPANIES AND STATES 15 2.1 THE HUMAN RIGHTS RESPONSIBILITIES OF COMPANIES 15 2.2 THE STATE DUTY TO PROTECT 17 3.