Navigating Changechange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Triage Or Injurious Neglect in Endangered Species Recovery

Conservation triage or injurious neglect in endangered species recovery Leah R. Gerbera,1 aCenter for Biodiversity Outcomes and School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287 Edited by James A. Estes, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA, and approved February 11, 2016 (received for review December 23, 2015) Listing endangered and threatened species under the US Endan- the ESA is presumed to offer a defense against extinction and a gered Species Act is presumed to offer a defense against extinction solution to achieve the recovery of imperiled populations (1), but and a solution to achieve recovery of imperiled populations, but only if effective conservation action ensues after listing occurs. only if effective conservation action ensues after listing occurs. The The amount of government funding available for species amount of government funding available for species protection protection and recovery is one of the best predictors of successful and recovery is one of the best predictors of successful recovery; recovery (2–7); however, government spending is both in- however, government spending is both insufficient and highly sufficient and highly disproportionate among groups of species disproportionate among groups of species, and there is significant (8). Most species recovery plans include cost estimates—a pro- discrepancy between proposed and actualized budgets across spe- posed budget for meeting recovery goals. Previous work has cies. In light of an increasing list of imperiled species requiring demonstrated a significant discrepancy between proposed and evaluation and protection, an explicit approach to allocating recovery actualized budgets across species (9). Furthermore, the literature fundsisurgentlyneeded. Here I provide a formal decision-theoretic on formal decision theory and endangered species conservation approach focusing on return on investment as an objective and a suggests that the most efficient allocation of resources to con- transparent mechanism to achieve the desired recovery goals. -

Website Address

website address: http://canusail.org/ S SU E 4 8 AMERICAN CaNOE ASSOCIATION MARCH 2016 NATIONAL SaILING COMMITTEE 2. CALENDAR 9. RACE RESULTS 4. FOR SALE 13. ANNOUNCEMENTS 5. HOKULE: AROUND THE WORLD IN A SAIL 14. ACA NSC COMMITTEE CANOE 6. TEN DAYS IN THE LIFE OF A SAILOR JOHN DEPA 16. SUGAR ISLAND CANOE SAILING 2016 SCHEDULE CRUISING CLASS aTLANTIC DIVISION ACA Camp, Lake Sebago, Sloatsburg, NY June 26, Sunday, “Free sail” 10 am-4 pm Sailing Canoes will be rigged and available for interested sailors (or want-to-be sailors) to take out on the water. Give it a try – you’ll enjoy it! (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club) Lady Bug Trophy –Divisional Cruising Class Championships Saturday, July 9 10 am and 2 pm * (See note Below) Sunday, July 10 11 am ADK Trophy - Cruising Class - Two sailors to a boat Saturday, July 16 10 am and 2 pm * (See note Below) Sunday, July 17 11 am “Free sail” /Workshop Saturday July 23 10am-4pm Sailing Canoes will be rigged and available for interested sailors (or want-to-be sailors) to take out on the water. Learn the techniques of cruising class sailing, using a paddle instead of a rudder. Give it a try – you’ll enjoy it! (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club) . Sebago series race #1 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) July 30, Saturday, 10 a.m. Sebago series race #2 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) Aug. 6 Saturday, 10 a.m. Sebago series race #3 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) Aug. -

Mpa Connections Special Issue on Tribal and Indigenous Peoples and Mpas July 2013

Hawaii Tourism Authority mpa connections Special Issue on Tribal and Indigenous Peoples and MPAs July 2013 In this issue: World Indigenous Network (WIN) Conference World Indigenous 1 Highlights International Indigenous Protected Areas Network Conference Aloha ‘Āina for Resource 2 Ervin Joe Schumacker that have supported the UNDRIP to act on the Management Marine Resources Scientist, Quinault Indian Nation Articles of that document. The Articles of the Member, MPA Federal Advisory Committee UNDRIP comprehensively recognize the basic Cultural Survival in 4 rights of indigenous peoples to self- Alaska’s Pribilof Islands In May 2013, over 1,200 delegates and determination and maintenance of their representatives from more than 50 countries Chumash Marine 6 cultures and homelands. This document has from every corner of the globe attended the Stewardship Program recently gained the support of four countries World Indigenous Network (WIN) that withheld their support initially: the United Worldwide Voyage of 7 Conference in Darwin, Australia. The Larrakia States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. the Hōkūle‘a Nation of Northern Australia are the Though each of these nations have their own 9 traditional owners of what is now the Darwin Indigenous Cultural internal policies for consultation and Landscapes area and they were gracious and warm hosts recognition of indigenous peoples, the for this important gathering. Characterizing Tribal 10 UNDRIP is a much more detailed recognition Cultural Landscapes The event brought indigenous land and sea of native rights and needs. managers together from around the world to Revitalizing Traditional 12 Many presentations and discussions recognized learn from each other and identify issues of Hawai’ian Fishponds the cultural landscapes of native peoples. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR RICHARD M. MILES Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: February 2, 2007 Copyright 2015 ADST FOREIGN SERVICE POSTS Oslo, Norway. Vice-Consul 1967-1969 Washington. Serbo-Croatian language training. 1969-1970 Belgrade, Yugoslavia. Consul 1970-1971 Belgrade, Yugoslavia. Second Secretary, Political Section 1971-1973 Washington. Soviet Desk 1973-1975 Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany. US Army Russian Institute 1975-1976 Advanced Russian language training Moscow. Second Secretary. Political Section 1976-1979 Washington. Yugoslav Desk Officer 1979-1981 Washington. Politico-Military Bureau. Deputy Director, PM/RSA 1981-1982 Washington. Politico-Military Bureau. Acting Director, PM/RSA 1982-1983 Washington. American Political Science Association Fellowship 1983-1984 Worked for Senator Hollings. D-SC Belgrade. Political Counselor 1984-1987 Harvard University. Fellow at Center for International Affairs 1987-1988 Leningrad. USSR. Consul General 1988-1991 Berlin, Germany. Leader of the Embassy Office 1991-1992 Baku. Azerbaijan. Ambassador 1992-1993 1 Moscow. Deputy Chief of Mission 1993-1996 Belgrade. Chief of Mission 1996-1999 Sofia, Bulgaria. Ambassador 1999-2002 Tbilisi, Georgia. Ambassador 2002-2005 Retired 2005 INTERVIEW Q: Today is February 21, 2007. This is an interview with Richard Miles, M-I-L-E-S. Do you have a middle initial? MILES: It’s “M” for Monroe, but I seldom use it. And I usually go by Dick. Q: You go by Dick. Okay. And this is being done on behalf of the Association of Diplomatic Studies and Training and I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. Well Dick, let’s start at the beginning. -

Ohana Waikiki Malia by Outrigger 2221 Kuhio Avenue

AVAILABLE FOR LEASE OHANA WAIKIKI MALIA BY OUTRIGGER 2221 KUHIO AVENUE KA LA KA UA A VE ALA WAI CANAL ALA WAI CANAL ALA WAI BLVD ALA WAI BLVD AQUA SKYLINE MOUNTAI N VIEW DR Lor AT ISLAND E COLONY V T T S I A E S I V ALOHA DR N TUSITALA ST E TUSITALA A A ST ST L I LA INA U O N NIU ST IU ʻ PAU ST A K AL AH ALA L W N KA SURFJACK KA A U A K NOHONANI ST KAIOLU ST KAIOLU A ST LAUNIU HOTEL MANUKAI ST KEONIANA ST KUAMOO ST NAMAHANA ST OLOHANA ST V KAPILI ST CLEGH KALAIMOKU ST E O O RN S T U ʻ KANEKAP HILTON I E L COURTYARD I N GARDEN INN L WAIKIKI E A HALA KAHIKI WAIKIKI BEACH I ST V N R UE A KUH IO AVE D OHANA MALIA I KUHIO AVE PU A EN N MARINE K HILTON V HYATT A ASTON SURF L RITZ CENTRIC WAIKIKI AT THE KING KALAKUA WAIKIKI THE LAYLOW, IU U A CARLTON WAIKIKI OHANA ʻ BEACH WAIKIKI L D PARK AUTOGRAPH WAIKIKI EAST KUH U V T BEACH KA IO AV BANYAN COLLECTION E H L TOWER WAIKOLU WY SEASIDE AVE B GALLERIA A ASTON BY DFS, P A WAIKIKI SUNSET E HAWAII AN N LUANA WAIKIKI LEWERS ST N L KA RO A INTERNATIONAL E HOB HOTEL & SUITES L PRINCE EDW O AUU MARKETPLACE AR V L D ST M A KING’S VILLAGE A WAIKIKI KUHIO ST I A AVE SHOPPING CENTER N BEACH AV L LAUULA ST E I A AVE DUKE’S LN WAIKIKI MARRIOTT A I WAIKIKI BUSINESS PLAZA N HYATT PLACE RESORT RESORT & WAIKIKI A AL WAIKIKI BEACH K L AL SHOPPING K HOTEL K AN SPA A O L K SHERATON U A AVE A PLAZA I ROYAL HAWAIIAN AVE HAWAIIAN ROYAL U ʻ A UO A PRINCESS ʻ WAIKIKI BEACHCOMBER A VE E BY OUTRIGGER HYATT REGENCY WAIKIKI KAIULANI K LI V CA WAIKIKI BEACH RESORT & SPA BEACHSIDE ASTON WAIKIKI I LOHI RTW L A A R N HOTEL BEACH -

James Wharram and Hanneke Boon

68 James Wharram and Hanneke Boon 11 The Pacific migrations by Canoe Form Craft James Wharram and Hanneke Boon The Pacific Migrations the canoe form, which the Polynesians developed into It is now generally agreed that the Pacific Ocean islands superb ocean-voyaging craft began to be populated from a time well before the end of The Pacific double ended canoe is thought to have the last Ice Age by people, using small ocean-going craft, developed out of two ancient watercraft, the canoe and originating in the area now called Indonesia and the the raft, these combined produce a craft that has the Philippines It is speculated that the craft they used were minimum drag of a canoe hull and maximum stability of based on either a raft or canoe form, or a combination of a raft (Fig 111) the two The homo-sapiens settlement of Australia and As the prevailing winds and currents in the Pacific New Guinea shows that people must have been using come from the east these migratory voyages were made water craft in this area as early as 6040,000 years ago against the prevailing winds and currents More logical The larger Melanesian islands were settled around 30,000 than one would at first think, as it means one can always years ago (Emory 1974; Finney 1979; Irwin 1992) sail home easily when no land is found, but it does require The final long distance migratory voyages into the craft capable of sailing to windward Central Pacific, which covers half the worlds surface, began from Samoa/Tonga about 3,000 years ago by the The Migration dilemma migratory group -

Papahānaumokuākea United States of America

PAPAHĀNAUMOKUĀKEA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Papahānaumokuākea is the name given to a vast and isolated linear cluster of small, low lying islands and atolls, with their surrounding ocean, extending some 1,931 km to the north west of the main Hawaiian Archipelago, located in the north-central Pacific Ocean. The property comprises the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (PMNM), which extends almost 2,000 km from southeast to northwest in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI). COUNTRY United States of America NAME Papahānaumokuākea MIXED WORLD HERITAGE SITE 2010: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under cultural criteria (iii) and (vi) and natural criteria (viii), (ix) and (x). STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE The UNESCO World Heritage Committee issued the following Statement of Outstanding Universal Value at the time of inscription: Brief Synthesis The property includes a significant portion of the Hawai’i-Emperor hotspot trail, constituting an outstanding example of island hotspot progression. Much of the property is made up of pelagic and deepwater habitats, with notable features such as seamounts and submerged banks, extensive coral reefs, lagoons and 14 km2 emergent lands distributed between a number of eroded high islands, pinnacles, atoll islands and cays. With a total area of around 362,075 km2 it is one of the largest marine protected areas in the world. The geomorphological history and isolation of the archipelago have led to the development of an extraordinary range of habitats and features, including an extremely high degree of endemism. Largely as a result of its isolation, marine ecosystems and ecological processes are virtually intact, leading to exceptional biomass accumulated in large apex predators. -

Nov/Dec 2019

The official publication of the OUTRIGGER CANOE CLUB N O V – D E C 2 0 1 9 H O H E L T I D O A T Y S N I ! P O R D november / december 2019 | AMA OFC1 Every Detail Designed, Inside and Out. Kō‘ula seamlessly blends an innovative, indoor design with spacious, private lānai that connect you to the outdoors. Designed by the award-winning Studio Gang Architects, every tower fl oor plan has been oriented to enhance views of the ocean. Kō‘ula also off ers curated interior design solutions by acclaimed, global design fi rm, Yabu Pushelberg. Outside, Kō‘ula is the fi rst Ward Village residence located next to Victoria Ward Park. This unique, central location puts you in the heart of Ward Village, making everything the neighborhood has to off er within walking distance. This holistically designed, master-planned community is home to Hawaii’s best restaurants, local boutiques and events, all right outside your door. 1, 2 & 3 bedroom homes available. Contact the Ward Village Residential Sales Gallery to schedule a private tour. 808.892.3196 | explore-koula.com 1240 Ala Moana Blvd. Honolulu, Hawaii 96814 Ward Village Properties, LLC | RB-21701 THIS IS NOT INTENDED TO BE AN OFFERING OR SOLICITATION OF SALE IN ANY JURISDICTION WHERE THE PROJECT IS NOT REGISTERED IN ACCORDANCE WITH APPLICABLE LAW OR WHERE SUCH OFFERING OR SOLICITATION WOULD OTHERWISE BE PROHIBITED BY LAW. WARD VILLAGE, A MASTER PLANNED DEVELOPMENT IN HONOLULU, HAWAII, IS STILL BEING CONSTRUCTED. ANY VISUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF WARD VILLAGE OR THE CONDOMINIUM PROJECTS THERIN, INCLUDING THEIR LOCATION, UNITS, COMMON ELEMENTS AND AMENITIES, MAY NOT ACCURATELY PORTRAY THE MASTER PLANNED DEVELOPMENT OR ITS CONDOMINIUM PROJECTS. -

Pacific Colonisation and Canoe Performance: Experiments in the Science of Sailing

PACIFIC COLONISATION AND CANOE PERFORMANCE: EXPERIMENTS IN THE SCIENCE OF SAILING GEOFFREY IRWIN University of Auckland RICHARD G.J. FLAY University of Auckland The voyaging canoe was the primary artefact of Oceanic colonisation, but scarcity of direct evidence has led to uncertainty and debate about canoe sailing performance. In this paper we employ methods of aerodynamic and hydrodynamic analysis of sailing routinely used in naval architecture and yacht design, but rarely applied to questions of prehistory—so far. We discuss the history of Pacific sails and compare the performance of three different kinds of canoe hull representing simple and more developed forms, and we consider the implications for colonisation and later inter-island contact in Remote Oceania. Recent reviews of Lapita chronology suggest the initial settlement of Remote Oceania was not much before 1000 BC (Sheppard et al. 2015), and Tonga was reached not much more than a century later (Burley et al. 2012). After the long pause in West Polynesia the vast area of East Polynesia was settled between AD 900 and AD 1300 (Allen 2014, Dye 2015, Jacomb et al. 2014, Wilmshurst et al. 2011). Clearly canoes were able to transport founder populations to widely-scattered islands. In the case of New Zealand, modern Mäori trace their origins to several named canoes, genetic evidence indicates the founding population was substantial (Penney et al. 2002), and ancient DNA shows diversity of ancestral Mäori origins (Knapp et al. 2012). Debates about Pacific voyaging are perennial. Fifty years ago Andrew Sharp (1957, 1963) was sceptical about the ability of traditional navigators to find their way at sea and, more especially, to find their way back over long distances with sailing directions for others to follow. -

*Wagner Et Al. --Intro

NUMBER 60, 58 pages 15 September 1999 BISHOP MUSEUM OCCASIONAL PAPERS HAWAIIAN VASCULAR PLANTS AT RISK: 1999 WARREN L. WAGNER, MARIE M. BRUEGMANN, DERRAL M. HERBST, AND JOEL Q.C. LAU BISHOP MUSEUM PRESS HONOLULU Printed on recycled paper Cover illustration: Lobelia gloria-montis Rock, an endemic lobeliad from Maui. [From Wagner et al., 1990, Manual of flowering plants of Hawai‘i, pl. 57.] A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF THE RECORDS OF THE HAWAII BIOLOGICAL SURVEY FOR 1998 Research publications of Bishop Museum are issued irregularly in the RESEARCH following active series: • Bishop Museum Occasional Papers. A series of short papers PUBLICATIONS OF describing original research in the natural and cultural sciences. Publications containing larger, monographic works are issued in BISHOP MUSEUM four areas: • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Anthropology • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Botany • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Entomology • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Zoology Numbering by volume of Occasional Papers ceased with volume 31. Each Occasional Paper now has its own individual number starting with Number 32. Each paper is separately paginated. The Museum also publishes Bishop Museum Technical Reports, a series containing information relative to scholarly research and collections activities. Issue is authorized by the Museum’s Scientific Publications Committee, but manuscripts do not necessarily receive peer review and are not intended as formal publications. Institutions and individuals may subscribe to any of the above or pur- chase separate publications from Bishop Museum Press, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817-0916, USA. Phone: (808) 848-4135; fax: (808) 841-8968; email: [email protected]. Institutional libraries interested in exchanging publications should write to: Library Exchange Program, Bishop Museum Library, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817-0916, USA; fax: (808) 848-4133; email: [email protected]. -

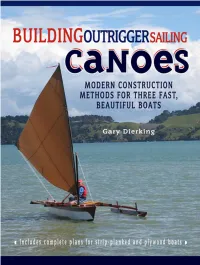

Building Outrigger Sailing Canoes

bUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES INTERNATIONAL MARINE / McGRAW-HILL Camden, Maine ✦ New York ✦ Chicago ✦ San Francisco ✦ Lisbon ✦ London ✦ Madrid Mexico City ✦ Milan ✦ New Delhi ✦ San Juan ✦ Seoul ✦ Singapore ✦ Sydney ✦ Toronto BUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES Modern Construction Methods for Three Fast, Beautiful Boats Gary Dierking Copyright © 2008 by International Marine All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-159456-6 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-148791-3. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw-Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent. -

A 1. Vbl. Par. 1St. Pers. Sg. Past & Present

A A 1. vbl. par. 1st. pers. sg. past & present - I - A peiki, I refuse, I won't, I can't. A ninayua kiweva vagagi. I am in two minds about a thing. A gisi waga si laya. I see the sails of the canoes. (The pronoun yaegu I, needs not to be expressed but for emphasis, being understood from the verbal particle.) 2. Abrev. of AMA. A-ma-tau-na? Which this man? 3. changes into E in dipthongues AI? EL? E. Paila, peila, pela. Wa valu- in village - We la valu - in his village. Ama toia, Ametoia, whence. Amenana, Which woman? Changes into I, sg. latu (son) pl. Litu -- vagi, to do, ku vigaki. Changes into O, i vitulaki - i vituloki wa- O . Changes into U, sg. tamala, father, - Pl. tumisia. sg. tabula gd.-father, pl. tubula. Ama what, amu, in amu ku toia? Where did you come from? N.B. several words beginning with A will be found among the KA 4. inverj. of disgust, disappointment. 5. Ambeisa wolaula? How Long? [see page 1, backside] ageva, or kageva small, fine shell disks. (beads in Motu) ago exclaims Alas! Agou! (pain, distress) agu Adj. poss. 1st. pers. sg. expressing near possession. See Grammar. Placed before the the thing possessed. Corresponds to gu, which is suffixed to the thing possessed. According to the classes of the nouns in Melanesian languages. See in the Grammar differences in Boyova. Memo: The other possess. are kagu for food, and ula for remove possession, both placed before the things possessed. Dabegu, my dress or dresses, - the ones I am wearing.