Comparing Two Organizational Structures in Professional Ultimate Jack Dowling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013-14 UCLA Women's Basketball Schedule

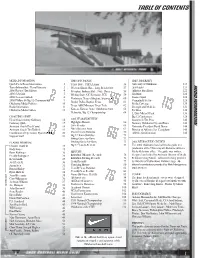

Table of Contents 5 12 51 Noelle Quinn Atonye Nyingifa Cori Close The 2013-14 Bruins UCLA's Top Single-Season Team Performances .......35 Credits Freshman Single-Season Leaders .................................36 Table of Contents .............................................................. 1 The 2013-14 UCLA Women’s Basketball Record Book was compiled Class Single-Season Leaders ..........................................37 2013-14 Schedule .............................................................. 2 by Ryan Finney, Associate Athletic Communications Director, with Yearly Individual Leaders ................................................38 assistance from Liza David, Director of Athletic Communications, Radio/TV Roster ................................................................ 3 By the Numbers ..............................................................40 Special assistance also provided by James Ybiernas, Assistant Athletic Alphabetical & Numerical Rosters .................................4 UCLA’s Home Court Records .....................................41 Communications Director and Steve Rourke, Associate Athletic Head Coach Cori Close ...................................................5 Communications Director. Primary photography by ASUCLA Pauley Pavilion - Home of the Bruins ..........................42 Assistant Coach Shannon Perry ..................................... 6 Campus Studio (Don Liebig and Todd Cheney). Additional photos provided by Scott Chandler, Thomas Campbell, USA Basketball, Assistant Coach Tony Newnan....................................... -

Teamup AUDL Power Rankings 6/22/21

TeamUp Fantasy AUDL Power Rankings (6/24 - 6/30) https://www.teamupfantasy.com/ 1. New York Empire The Empire are still in the number one spot this week. Last weekend they had a game against the Thunderbirds and won easily. They should get another win against the Cannons next week. A real test for the Empire will be in two weeks, when they face the Breeze. 2. Chicago Union Chicago had a great weekend; they beat the Mechanix 30-13 and advanced to 3-0 on the season. Danny Miller played extremely well for them and earned player of the game from the Union. Their next game is against the AlleyCats, who have only beaten the Mechanix this year. 3. DC Breeze The game last weekend for the Breeze was amazing. Their offense and defense both had completion percentages above 90. Young players such as Jacques Nissen and Duncan Fitzgerald stepped up and played well. A.J. Merriman had a huge performance with 3 blocks and 6 scores. They are moving up a spot this week. 4. Raleigh Flyers The Flyers are moving down a spot this week, but that is only because the Breeze played exceptionally well. The Flyers got their first win of the season last weekend and have an easier schedule on the horizon. The next three games they play should be easy wins. 5. Dallas Roughnecks Dallas is staying in the same spot this week. They have only played two games and are currently 1-1. Even though they have only played two games, they did beat a good Aviators team this week. -

Teamup AUDL Power Rankings

TeamUp Fantasy AUDL Power Rankings (7/8 - 7/14) https://www.teamupfantasy.com/ 1. Chicago Union The Union have earned the number one spot this week. They are now 5-0 after their win against the Radicals. Chicago's offense has so many weapons and they manage to take smart shots. In their game this past weekend, their defense played better than they have before. If they keep up this level of play they will have a good shot at the title. 2. DC Breeze DC is moving up a spot this week. Last weekend they beat the Empire in impressive fashion. They won by three, but New York scored a couple goals in the final minutes of the game. DC’s offense performed extremely well - as they always do - and their defense managed to get a ton of run through Ds. 3. New York Empire New York is stepping down from their pedestal this week. After being at the top for the first five weeks of the season, the Empire lost to the Breeze. The Empire allowed the Breeze to get too many run through Ds that could have been fixed. The Empire are still a great team and are still scary to face. 4. Raleigh Flyers The Flyers managed to beat the Cannons last week. With that being said, they are staying in the number four spot this week. They have another game against the Cannons next week, which should be another easy win. This team has a lot of potential to make it deep into the playoffs this year. -

Spring 2016 at Last - a Neighborhood Grocery Store! Festival Foods to Open April 8

TENNEY - LAPHAM NEIGHBORHOOD ASSOCIATION NEWSLETTER Spring 2016 At Last - A Neighborhood Grocery Store! Festival Foods to Open April 8 Photos by Bob Shaw 1 TLNA Neighborhood2015-2016 Council TLNA Neighborhood Council President Patty Prime 432 Sidney [email protected] (608) 251-1937 Vice President Sue Babcock 425 N. Livingston St. [email protected] (608) 213-0814 Secretary Lisa Hoff 123 N. Blount [email protected] (608) 298-8943 Treasurer Steven Maerz 638 E. Mifflin St. [email protected] (608) 251-1495 Business Steve Wilke 824 E. Johnson St. [email protected] (608) 609-5320 Development Patrick Heck 123 N. Blount, #303 [email protected] (608) 628-6255 Housing Keith Wessel 307 N. Ingersoll St. [email protected] (608) 256-1480 Membership Richard Linster 432 Sidney [email protected] (608) 251-1937 Social Marta Staple 461 N. Baldwin [email protected] (608) 347-2161 Parks Tyler Lark 842 E. Dayton St. [email protected] (920) 737-3538 Publicity/Newsletter Jessi Mulhall 1423 E. Johnson St. [email protected] (608) 228-4630 Transportation/Safety Bob Klebba 704 E. Gorham St. [email protected] (608) 209-8100 Area A Mary Beth Collins 1245 E. Mifflin St. [email protected] (608) 358-4448 Area B Sarah Herrick 208 N. Brearly St. [email protected] (920) 265-5751 Area C Matt Lieber 328 N. Baldwin St. [email protected] (608) 665-3300 Area D Mark Bennett 10 N. Livingston St. [email protected] (414) 861-5498 TLNA2015-2016 Neighborhood Council Tenney-Lapham Corporation President Cheryl Wittke 446 Sidney Street [email protected] (608) 256-7421 Vice President Robert Kasdorf 334 Marston Ave. -

Democracy Found

Democracy Found A Nonpartisan Business Case for Political Innovation in Wisconsin Elections Rotary Club of La Crosse, September 17, 2020 The Problem “Washington isn’t broken – it’s doing what it’s designed to do.” – Mickey Edwards Acting in the Likelihood of public interest getting reelected Copyright 2019 © Katherine M. Gehl The Solution: Final-Five Voting Top-Five Primaries General Election What is your favorite Wisconsin professional sports franchise? Admirals Milwaukee Party Brewers Milwaukee Party Bucks Milwaukee Party Forward Madison Party Packers GB Party Problem Solved “America was founded on the greatest political innovation of modern times and political innovation is key to our future.” Acting in Likelihood of the public getting interest reelected Copyright 2019 © Katherine M. Gehl 6 DemocracyFound.org 7 Join us! Add Your Support & Stay Connected www.DemocracyFound.org Slide Appendix Potential Q&A Election Results GMC Spring 2019 Example Results Primary Election General Election Primary What is your favorite Wisconsin professional sports franchise? Election Fill in the oval next to your choice, like this : Beloit Snappers Beloit Party Forward Madison Madison Party Green Bay Blizzard GB Party Green Bay Packers GB Party Milwaukee Admirals Milwaukee Party Milwaukee Brewers Milwaukee Party Milwaukee Bucks Milwaukee Party Milwaukee Wave Milwaukee Party Wisconsin Herd Oshkosh Party Wisconsin Timber Rattlers Appleton Party Primary Election Results Beloit Snappers 3% Forward Madison 8% Green Bay Blizzard 6% Green Bay Packers 23% Madison -

Chadha-Chase-102920 0001.Pdf

GUYTON N. JINKERSON LAWY E F] 333 WEST SANTA CLAf3A STFiE:E:T SUITE: 7C)C) SAN .OSE:, CALIFC)RNIA 95H3 TELEPHONE:: 4Oe.297.s555 IIAND DELIVERED October 29, 2020 John Chase Deputy District Attorney 70 West Hedding Street San Jose, California 95110 Re: Grand Jury Investigation Regarding CCWs Dear Mr. Chase: A grand jury operates as part of the charging process of criminal procedure, and its function is viewed as investigatory, not adjudicatory, in nature. (People v. Brown (1999) 75 Cal.App.4th 916, 931-932.) In performing its investigatory function, the grand jury decides if a crime has been committed and whether there is probable cause to indict the accused. (Id. at p. 931; Culrmiskey v. Superior Court (1992) 3 Cal.4th 1018,1026.) Probable cause exists if there is a "`"strong suspicion"" of guilt. (Cujnlniskey, at p.1029, italics omitted. ) The grand jury conducts its investigation in secret, without notice to or participation by the defendant. (People v. Superior Court (Mouchaourab) (2000) ]8 Cat.PLpp.4tt\ 403, 414-415.) The district attorney may appear before the grand jury to give information or advice or to question witnesses. (Jbic].) Although the prosecution participates in the grand jury proceedings, it is essential to the proper functioning of the grand jury system that the grand jury operate independently of the prosecution. (People v. Backus (1979) 23 Cal.3d 360, 392-393.) The grand jury is viewed "`as a protective bulwark standing solidly between the ordinary citizen and an overzealous prosecutor"' and its mission "`is to clear the innocent, no less than to bring to trial those Who may be guilty.'" (Johnson v. -

Successful Indoor Soccer Business & 46,000 SF Facility for Sale Break

Successful Indoor Soccer Business & 46,000 SF Facility for Sale Break Away Sports Center, Inc. 5964 Executive Drive, Fitchburg, Wisconsin Company Overview: Since 1996, Break Away Sports Center “Break Away” has offered a state of the art, well maintained, 46,000 sq. ft. sports facility that accommodates Madison’s indoor sporting needs, providing a place where soccer enthusiasts, no matter the skill level, can enjoy a range of recreational soccer programs. The facility includes two large well-lit indoor soccer playing fields with state-of-the-art EPDM infill turf, locker rooms, permanent concessions space, viewing area, offices for Break Away, along with additional office space leased to complimentary sports related organizations. Break Away is operated by professional instructors, experienced referees and a staff that is passionate about providing indoor soccer opportunities in the community. Break Away offers a variety of programs, tailored specifically for each age group (toddlers to adults) and for all talent levels. Even though obtained from sources deemed reliable, no warranty or representation, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy of the information herein, and it is subject to errors, omissions, change of price, rental or other conditions, withdrawal without notice, and to any special listing conditions imposed by our principals. www.cresa.com/madison Cresa Madison Business Profile: Legal Business Name: Break Away Sports Center, Inc. Business Type: S-Corp Year Established: 1996 by three soccer enthusiasts, Matt Lombardino, Mark Landgraf & Jeff Annen Building Address: 5964 Executive Drive, Fitchburg, WI 53719 Website Address: www.breakawaysports.com Hours of Operation: Weekdays: 1:00 p.m. -

Splash Pad Open Again County Lifting All Health Restrictions June 2

I’m alwI’May STILLs her HERE!e for you! It’s your paper! 27 years in VASD Housing Market Kathy Bartels Friday, June 11, 2021 • Vol. 8, No. 4 • Fitchburg, WI • ConnectFitchburg.com • $1 608-235-2927 [email protected] adno=223164 Inside City of Fitchburg Encompass Health Staff no proposes rehab center longer require Page 3 masks in city buildings, spaces Mayor says while face coverings are encouraged, they will be optional City applies for EMILIE HEIDEMANN grants for The Hub Unified Newspaper Group City buildings and public spaces Page 8 have reopened again after just over a year of closures because of the Sports COVID-19 pandemic. Photo by Benjamin Pierce And people are no longer required 4-year-old Ben Lynch plays at the splash pad in McKee Farms Park on Wednesday, June 2, in Fitchburg. to wear masks or practice social Boys golf distancing in city spaces, Mayor Crusaders roll back Aaron Richardson told the Star, per Public Health Madison and Dane to state Splash pad open again County lifting all health restrictions June 2. The McKee Farms Park Page 14 splash pad, City Hall, 5520 Lacy Summer is here. hot temperatures. Road; the Fitchburg Public Library, That’s evidenced by how splash pad at McKee Email Emilie Heidemann at emilie.heidemann@ 5530 Lacy Road; and Senior Cen- Schools Farms Park officially reopened on June 1. wcinet.com or follow her on Twitter at @Heide- ter, 5510 Lacy Road, are among the Kids and families can now engage in spaces again operational, he said. VASD moves water-related fun and take a break from the mannEmilie. -

Brandon Moss Nich Conaway, 50 Nate Hammons, Aaron Reza Nate Hammons, 49 Steven Guerra 48 Brad Burns 47 Will Savage 46 Jon Shackelford 45 P.J

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION THE OPPONENTS THE UNIVERSITY Quick Facts/Team Information 2 Texas State, UTPA, Lamar 56 University of Oklahoma 114 M MEDIA INFORMATION Team Information / Travel Itinerary 3 Western Illinois, Rice, Long Beach State 57 Academics 118 E 2006 Roster / Breakdown 4 Memphis, Indiana State, Notre Dame 58 Athletics Excellence 122 D I 2006 Schedule 5 Wichita State, UC Riverside, TCU 59 Tradition 124 A 2006 Season Outlook 6 Sooner Spirit 126 I Centenary, Texas-Arlington, Arizona State 60 N 2006 Phillips 66 Big 12 Championship 9 Community Service 128 Baylor, Dallas Baptist, Texas 61 F Oklahoma Media Policies 10 Media Coverage 130 O Texas A&M, Missouri, Texas Tech 62 R Radio Information 11 Strength and Medicine 132 Oklahoma Media Outlets 12 Kansas, Kansas State, Oklahoma State 63 Facilities 134 M Nebraska, Big 12 Championship 64 L. Dale Mitchell Park 136 A T COACHING STAFF Big 12 Conference 138 I Head Coach Sunny Golloway 14 2005 YEAR-IN-REVIEW Sooners In The Pros 140 O N Golloway Q&A 17 Highlights/Honors 66 Norman, Oklahoma City and Tulsa 142 Assistant Coach Fred Corral 18 2005 Results 68 University President David Boren 144 Assistant Coach Tim Tadlock 19 Miscellaneous Stats 69 Director of Athletics Joe Castiglione 145 Coordinator of Operations Ryan Gaines 20 Overall Team Statistics 70 Athletic Administration 146 Support Staff 21 Big 12 Team Statistics 71 Hitting Game-by-Game 72 PLAYER PROFILES Pitching Game-by-Game 73 2006 MEDIA GUIDE CREDITS Chuckie Caufi eld 24 Big 12 Year-In-Review 74 The 2006 Oklahoma baseball media guide is a Kody Kaiser 25 production of the University of Oklahoma Athletics Ryan Rohlinger 26 HISTORY Media Relations offi ce. -

Winter/Spring 2019 Family Events

WINTER/SPRING 2019 FAMILY EVENTS Here at Girl Scouts of Northeast Texas we like to share the fun! Visit gsnetx.org/events for more details on each event and to register. Questions? email [email protected] Cost will vary per activity. Date Title PGL Date Title PGL He & Me Campout at She & Me Campout at 1/11 -13/19 All 3/1-3/19 All STEM Center of Excellence STEM Center of Excellence 1/18 -20/19 Family Campout at Gambill All 3/14/19 Girl Scout Birthday Party D | B | J 2/1-28/19 Capital One Coding Patch All 3/16/19 Camp Open House: Rocky Point All 2/2/19 Polar Plunge All 3/22-24/19 Family Campout at Rocky Point All 2/9/19 Dinosaur Light-Up Show Al 4/6/19 Covering the Bases of STEM All She & Me Campout at 2/16/19 Explore Engineering Day at UTD All 4/12-14/19 All STEM Center of Excellence Mission Military: Girl Scout Night 2/16/19 All with the Allen Americans 4/12- 14/19 Earth Day Patch Program All Girl Scout Day at Dallas 4/28/19 Flags for All All 2/17/19 All Children's Theater He & Me Campout She & Me Campout at 5/10-12/19 All 2/22-24/19 All at Rocky Point Bette Perot He & Me Campout at 5/17- 19/19 All 2/23/19 Brookhaven College STEM Fair All STEM Center of Excellence 3/1-3/19 Family Campout at Rocky Point All June Council-wide Bridging All Plus.. -

Noblesville Class of '68 Gives Back in a Big

TODAy’s WeaTHER SUNDAY, MAY 27, 2018 Today: Partly sunny with an isolated shower or storm possible in the afternoon. HERIDAN OBLESVIllE ICERO RCADIA Tonight: Partly cloudy, with an isolated S | N | C | A shower or storm possible in the early evening. IKE TLANTA ESTFIELD ARMEL ISHERS NEWS GATHERING L & A | W | C | F PARTNER FOllOW US! HIGH: 90 LOW: 69 Look for Noblesville Class of ’68 the helpers My mind is still From the Heart trying to process the gives back in a big way events that took place Friday, in my town, where I have lived all of my life. Our com- munity was shaken. My heart is hurt- ing. My emotions run from sadness to anger. JANET HART LEONARD Things like this don't happen here ... but it did. I wish I had the answers to these See Helpers . Page 2 President Trump commends Jason Seaman’s bravery WISH-TV | wishtv.com President Donald Trump tweeted out thanks for a man many are calling a hero for his actions during a school shooting in Noblesville. Jason Seaman, 29, is said to have stopped the shooter after the suspect shot a female student at Noblesville West Middle School on Friday. He was shot multiple times in the process. Photo provided The president Trump Recently at the Noblesville High School Alumni Banquet, the Noblesville High School class of 1968 presented a check tweeted: "Thanks to to the Noblesville High School Alumni Association in the amount of $16,500 – the largest donation given to date by any very brave Teacher & Hero Jason Seaman NHS reunion class. -

Teamup AUDL Power Rankings

TeamUp Fantasy AUDL Power Rankings (7/29 - 8/4) https://www.teamupfantasy.com/ 1. Atlanta Hustle Atlanta proved why they should be number one last weekend. They played the Empire and put on a clinic, winning by a score of 22-21. The junky zone the Hustle use makes opposing offenses make a lot of throws and increases the chance of a turnover. Atlanta’s defense works together well in this zone, almost looking like a machine. 2. New York Empire The Empire may have lost, but they are still moving up this week. They have locked it in after a couple shaky performances earlier in the season. Losing to the Hustle by just one is nothing to be ashamed of. Babbitt carried the Empire’s defense and got 4 blocks last week. 3. Chicago Union The Union are moving down a spot this week, but they didn’t play terribly. They beat the Wind Chill, who only had one loss before that game. Minnesota collected 13 blocks against them, but besides that they only had 7 other turnovers. Their offense, which is led by Janas, valued the disc and made the Wind Chill earn their turnovers. 4. DC Breeze The Breeze did not have a game last weekend, which could be a good or bad thing. They get rest, but this also gives them more time to think about their loss to the Hustle two weeks ago. Next week they face the Phoenix, which should be a win for the Breeze. 5. Raleigh Flyers Raleigh was another team that did not have a game last weekend.