Street Art As a Medium for Political Discourse in the Post-Soviet Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pussy Riot Affair: Gender and National Identity in Putin's Russia 1 Peter Rutland 2 the Pussy Riot Affair Was a Massive In

The Pussy Riot affair: gender and national identity in Putin’s Russia 1 Peter Rutland 2 The Pussy Riot affair was a massive international cause célèbre that ignited a widespread movement of support for the jailed activists around the world. The case tells us a lot about Russian society, the Russian state, and Western perceptions of Russia. It also raises interest in gender as a frame of analysis, something that has been largely overlooked in 20 years of work by mainstream political scientists analyzing Russia’s transition to democracy.3 There is general agreement that the trial of the punk rock group signaled a shift in the evolution of the authoritarian regime of President Vladimir Putin. However, there are many aspects of the affair still open to debate. Will the persecution of Pussy Riot go down in history as one of the classic trials that have punctuated Russian history, such as the arrest of dissidents Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel in 1966, or the trial of revolutionary Vera Zasulich in 1878? Or is it just a flash in the pan, an artifact of media fascination with attractive young women behaving badly? The case also poses a challenge for feminists. While some observers, including Janet Elise Johnson (below), see Pussy Riot as part of the struggle for women’s rights, others, including Valerie Sperling and Marina Yusupova, raise questions about the extent to Pussy Riot can be seen as advancing the feminist cause. Origins Pussy Riot was formed in 2011, emerging from the underground art group Voina which had been active since 2007. -

The Role of Political Art in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution

Resistance Graffiti: The Role of Political Art in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution Hayley Tubbs Submitted to the Department of Political Science Haverford College In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Professor Susanna Wing, Ph.D., Advisor 1 Acknowledgments I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to Susanna Wing for being a constant source of encouragement, support, and positivity. Thank you for pushing me to write about a topic that simultaneously scared and excited me. I could not have done this thesis without you. Your advice, patience, and guidance during the past four years have been immeasurable, and I cannot adequately express how much I appreciate that. Thank you, Taieb Belghazi, for first introducing me to the importance of art in the Arab Spring. This project only came about because you encouraged and inspired me to write about political art in Morocco two years ago. Your courses had great influence over what I am most passionate about today. Shukran bzaf. Thank you to my family, especially my mom, for always supporting me and my academic endeavors. I am forever grateful for your laughter, love, and commitment to keeping me humble. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………....…………. 1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………….……..3 The Egyptian Revolution……………………………………………………....6 Limited Spaces for Political Discourse………………………………………...9 Political Art………………………………………………………………..…..10 Political Art in Action……………………………………………………..…..13 Graffiti………………………………………………………………………....14 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………......19 -

Window Cleaning Magazine

Window Cleaning Jul/Aug 2016 magazine This issue… and much, much more… Issue 18 Window Cleaning Magazine Editorial Hey Readers, Do you know what one secret of success is? Its very simple - you have to love what you do. I remember in my early days as a trainee print sales man, I would have discussions with my Sales Manager about the 80 or so cold calls I had made in that day. He would tell me that I needed to smile on the phone! At first I thought he was crazy. What did it matter if I was not smiling on a phone call? The person on the other end cannot tell either way, right? Wrong! Within ten seconds of starting a sales call, a prospect would be able to tell if they are talking to beauty or the beast. I learned that smiling actually helped with the tone of my voice, and it is one way of positively affecting its inflection. Without smiling you can sound monotone and therefore come across as boring, or worse uninterested in the sales call you initiated. The reason is not psychological but rather physiological. When you smile, the soft palate at the back of your mouth raises and makes the sound waves more fluid. Smiling helps your voice sound friendly, warm, and receptive. I began to have a cavalier approach to sales calls. I never worried about not closing the deal, I started to have fun with the calls….. And do you know what? It got results. The more fun I had, the more deals I would close and I thought less of the calls that never went anywhere at all. -

The Mediation of the Concept of Civil Society in the Belarusian Press (1991-2010)

THE MEDIATION OF THE CONCEPT OF CIVIL SOCIETY IN THE BELARUSIAN PRESS (1991-2010) A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 IRYNA CLARK School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures ............................................................................................... 5 List of Abbreviations ....................................................................................................... 6 Abstract ............................................................................................................................ 7 Declaration ....................................................................................................................... 8 Copyright Statement ........................................................................................................ 8 A Note on Transliteration and Translation .................................................................... 9 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ 10 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 11 Research objectives and questions ................................................................................... 12 Outline of the Belarusian media landscape and primary sources ...................................... 17 The evolution of the concept of civil society -

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

Full Study (In English)

The Long Shadow of Donbas Reintegrating Veterans and Fostering Social Cohesion in Ukraine By JULIA FRIEDRICH and THERESA LÜTKEFEND Almost 400,000 veterans who fought on the Ukrainian side in Donbas have since STUDY returned to communities all over the country. They are one of the most visible May 2021 representations of the societal changes in Ukraine following the violent conflict in the east of the country. Ukrainian society faces the challenge of making room for these former soldiers and their experiences. At the same time, the Ukrainian government should recognize veterans as an important political stakeholder group. Even though Ukraine is simultaneously struggling with internal reforms and Russian destabilization efforts, political actors in Ukraine need to step up their efforts to formulate and implement a coherent policy on veteran reintegration. The societal stakes are too high to leave the issue unaddressed. gppi.net This study was funded by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Ukraine. The views expressed therein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation. The authors would like to thank several experts and colleagues who shaped this project and supported us along the way. We are indebted to Kateryna Malofieieva for her invaluable expertise, Ukraine-language research and support during the interviews. The team from Razumkov Centre conducted the focus group interviews that added tremendous value to our work. Further, we would like to thank Tobias Schneider for his guidance and support throughout the process. This project would not exist without him. Mathieu Boulègue, Cristina Gherasimov, Andreas Heinemann-Grüder, and Katharine Quinn-Judge took the time to provide their unique insights and offered helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. -

Human Rights for Musicians Freemuse

HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS FREEMUSE – The World Forum on Music and Censorship Freemuse is an international organisation advocating freedom of expression for musicians and composers worldwide. OUR MAIN OBJECTIVES ARE TO: • Document violations • Inform media and the public • Describe the mechanisms of censorship • Support censored musicians and composers • Develop a global support network FREEMUSE Freemuse Tel: +45 33 32 10 27 Nytorv 17, 3rd floor Fax: +45 33 32 10 45 DK-1450 Copenhagen K Denmark [email protected] www.freemuse.org HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS Ten Years with Freemuse Human Rights for Musicians: Ten Years with Freemuse Edited by Krister Malm ISBN 978-87-988163-2-4 Published by Freemuse, Nytorv 17, 1450 Copenhagen, Denmark www.freemuse.org Printed by Handy-Print, Denmark © Freemuse, 2008 Layout by Kristina Funkeson Photos courtesy of Anna Schori (p. 26), Ole Reitov (p. 28 & p. 64), Andy Rice (p. 32), Marie Korpe (p. 40) & Mik Aidt (p. 66). The remaining photos are artist press photos. Proofreading by Julian Isherwood Supervision of production by Marie Korpe All rights reserved CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Human rights for musicians – The Freemuse story Marie Korpe 9 Ten years of Freemuse – A view from the chair Martin Cloonan 13 PART I Impressions & Descriptions Deeyah 21 Marcel Khalife 25 Roger Lucey 27 Ferhat Tunç 29 Farhad Darya 31 Gorki Aguila 33 Mahsa Vahdat 35 Stephan Said 37 Salman Ahmad 41 PART II Interactions & Reactions Introducing Freemuse Krister Malm 45 The organisation that was missing Morten -

Harold E. Hofmann

the En español: LawndaLian¡Vea la pagina 11! Winter 2014 • Vol. 19 • No 4 • www.lawndalecity.org • (310) 973-3200 HAROLD E. HOFMANN 1932 - 2013 Mayor Harold Hofmann Passes Away Need a First Class On the morning of November 16, 2013, longtime Lawndale Venue for Your Event? Mayor and City Councilmember Harold Hofmann passed away peacefully of natural causes at the age of 81 at his The Lawndale Community Center has four home in Lawndale. Mayor Hofmann was born in Monte- state-of-the-art rooms with full amenities bello, California and came to Lawndale at a very young age. that are available for reservation for private He continued to live in Lawndale for the rest of his life and functions such as: birthday parties, baby in the same house he grew up in. He attended Lawndale showers, wedding receptions, business public schools and graduated from Leuzinger High School meetings, family gatherings, formal and continued his education at El Camino College. He dining events, etc. Whatever event you served in the United States Army for two years during the are having, the Lawndale Community Korean conflict specializing in heavy equipment operation. Center has a room that is made for just for your event. The following spaces are Mayor Hofmann truly loved the City and its people and available for reservation for large and faithfully served the City of Lawndale and its residents for small groups: over 33 years on the City Council as a Councilmember and then as Mayor. He was a tireless worker who was dedicated to making Lawndale a better place • Full Main Event Room – to live for its residents. -

Banksy at Disneyland: Generic Participation in Culture Jamming Joshua Carlisle Harzman University of the Pacific, [email protected]

Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research Volume 14 Article 3 2015 Banksy at Disneyland: Generic Participation in Culture Jamming Joshua Carlisle Harzman University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/kaleidoscope Recommended Citation Harzman, Joshua Carlisle (2015) "Banksy at Disneyland: Generic Participation in Culture Jamming," Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research: Vol. 14 , Article 3. Available at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/kaleidoscope/vol14/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Banksy at Disneyland: Generic Participation in Culture Jamming Cover Page Footnote Many thanks to all of my colleagues and mentors at the University of the Pacific; special thanks to my fiancé Kelly Marie Lootz. This article is available in Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/ kaleidoscope/vol14/iss1/3 Banksy at Disneyland: Generic Participation in Culture Jamming Joshua Carlisle Harzman Culture jamming is a profound genre of communication and its proliferation demands further academic scholarship. However, there exists a substantial gap in the literature, specifically regarding a framework for determining participation within the genre of culture jamming. This essay seeks to offer such a foundation and subsequently considers participation of an artifact. First, the three elements of culture jamming genre are established and identified: artifact, distortion, and awareness. Second, the street art installment, Banksy at Disneyland, is analyzed for participation within the genre of culture jamming. -

A Militant Reconfiguration of Peter Bürger's “Neo-Avant-Garde”

Counter Cultural Production: A Militant Reconfiguration of Peter Bürger’s “Neo-Avant-Garde” Martin Lang Abstract This article re-examines Peter Bürger’s negative assessment of the neo-avant-garde as apolitical, co-opted and toothless. It argues that his conception can be overturned through an analysis of different sources – looking beyond the usual examples of individual artists to instead focus on the role of more politically committed collectives. It declares that, while the collectives analysed in this text do indeed appropriate and develop goals and tactics of the ‘historical avant-garde’ (hence meriting the appellation ‘neo-avant-garde’), they cannot be accused of being co-opted or politically uncommitted due to the ferocity of their critique of, and attack on, art and political institutions. Introduction Firstly, the reader should be aware that my understanding of the avant-garde has nothing to do with how Clement Greenberg used the term.1 I am aligning myself with Peter Bürger’s position that the ‘historical avant-garde’ was, primarily, Dada and Surrealism, but also the Russian avant-gardes after the October revolution and Futurism.2 These are movements that Greenberg saw as peripheral to the avant-garde. Greenberg did, however, share some of Bürger’s concerns about the avant-garde’s institutionalisation, or ‘academisation’ as he would put it. I borrow the term ‘neo-avant-garde’ from Bürger, but with some trepidation. In Theorie der Avantgarde (1974 – translated into English as Theory of the Avant-Garde 1984) he describes the neo-avant-garde of the 1950s and 1960s as movements that revisit the historical avant- garde, but he dismisses them as inherently compromised: The neo-avant-garde institutionalizes the avant-garde as art and thus negates genuinely avant-gardiste intentions. -

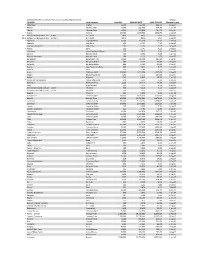

Maximum Monthly Stipend Rates For

MAXIMUM MONTHLY STIPEND RATES FOR FELLOWS AND SCHOLARS Jul 2020 COUNTRY Local Currency Local DSA MAX RES RATE MAX TRV RATE Effective % date * Afghanistan Afghani 12,600 132,300 198,450 1-Aug-07 * Albania Albania Lek(e) 14,000 220,500 330,750 1-Jan-05 Algeria Algerian Dinar 31,600 331,800 497,700 1-Aug-07 * Angola Kwanza 133,000 1,396,500 2,094,750 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Apr. - 30 Nov.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Dec. - 31 Mar.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 * Argentina Argentine Peso 18,600 153,450 230,175 1-Jan-05 Australia AUL Dollar 453 4,757 7,135 1-Aug-07 Australia - Academic AUL Dollar 453 1,200 7,135 1-Aug-07 * Austria Euro 261 2,741 4,111 1-Aug-07 * Azerbaijan (new)Azerbaijan Manat 239 1,613 2,420 1-Jan-05 Bahrain Bahraini Dinar 106 2,226 3,180 1-Jan-05 Bahrain - Academic Bahraini Dinar 106 1,113 1,670 1-Aug-07 Bangladesh Bangladesh Taka 12,400 130,200 195,300 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 * Belarus New Belarusian Ruble 600 5,850 8,775 1-Jan-06 Belgium Euro 338 3,549 5,324 1-Aug-07 Benin CFA Franc(XOF) 123,000 1,291,500 1,937,250 1-Aug-07 Bhutan Bhutan Ngultrum 7,290 76,545 114,818 1-Aug-07 * Bolivia Boliviano 1,200 10,800 16,200 1-Jan-07 * Bosnia and Herzegovina Convertible Mark 279 3,557 5,336 1-Jan-05 Botswana Botswana Pula 2,220 23,310 34,965 1-Aug-07 Brazil Brazilian Real 530 4,373 6,559 1-Jan-05 British Virgin Islands (16 Apr. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic