Clinical Research in Dermatology: Open Access Open Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role of NS1 Antibodies in the Pathogenesis of Acute Secondary Dengue Infection

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-07667-z OPEN Role of NS1 antibodies in the pathogenesis of acute secondary dengue infection Deshni Jayathilaka1, Laksiri Gomes1, Chandima Jeewandara1, Geethal.S.Bandara Jayarathna1, Dhanushka Herath1, Pathum Asela Perera1, Samitha Fernando1, Ananda Wijewickrama2, Clare S. Hardman3, Graham S. Ogg3 & Gathsaurie Neelika Malavige 1,3 The role of NS1-specific antibodies in the pathogenesis of dengue virus infection is poorly 1234567890():,; understood. Here we investigate the immunoglobulin responses of patients with dengue fever (DF) and dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) to NS1. Antibody responses to recombinant-NS1 are assessed in serum samples throughout illness of patients with acute secondary DENV1 and DENV2 infection by ELISA. NS1 antibody titres are significantly higher in patients with DHF compared to those with DF for both serotypes, during the critical phase of illness. Furthermore, during both acute secondary DENV1 and DENV2 infection, the antibody repertoire of DF and DHF patients is directed towards distinct regions of the NS1 protein. In addition, healthy individuals, with past non-severe dengue infection have a similar antibody repertoire as those with mild acute infection (DF). Therefore, antibodies that target specific NS1 epitopes could predict disease severity and be of potential benefit in aiding vaccine and treatment design. 1 Centre for Dengue Research, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Nugegoda 10100, Sri Lanka. 2 National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Angoda 10250, Sri Lanka. 3 MRC Human Immunology Unit, Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, Oxford NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford OX3 9DS, UK. These authors contributed equally: Deshni Jayathilaka, Laksiri Gomes. The authors jointly supervised this work: Graham S. -

Corneal Endotheliitis with Cytomegalovirus Infection of Persisted

Correspondence 1105 Sir, resulted in gradual decreases of KPs, but graft oedema Corneal endotheliitis with cytomegalovirus infection of persisted. Vision decreased to 20/2000. corneal stroma The patient underwent a second keratoplasty combined with cataract surgery in August 2007. Although involvement of cytomegalovirus (CMV) in The aqueous humour was tested for polymerase corneal endotheliitis was recently reported, the chain reaction to detect HSV, VZV, or CMV; a positive pathogenesis of this disease remains uncertain.1–8 Here, result being obtained only for CMV-DNA. Pathological we report a case of corneal endotheliitis with CMV examination demonstrated granular deposits in the infection in the corneal stroma. deep stroma, which was positive for CMV by immunohistochemistry (Figures 2a and b). The cells showed a typical ‘owl’s eye’ morphology (Figure 2c). Case We commenced systemic gancyclovir at 10 mg per day A 44-year-old man was referred for a gradual decrease in for 7 days, followed by topical 0.5% gancyclovir eye vision with a history of recurrent iritis with unknown drops six times a day. With the postoperative follow-up aetiology. The corrected visual acuity in his right eye was period of 20 months, the graft remained clear without 20/200. Slit lamp biomicroscopy revealed diffuse corneal KPs (Figure 1d). The patient has been treated with oedema with pigmented keratic precipitates (KPs) gancyclovir eye drops t.i.d. to date. His visual acuity without anterior chamber cellular reaction (Figure 1a). improved to 20/20, and endothelial density was The patient had undergone penetrating keratoplasty in 2300/mm2. Repeated PCR in aqueous humour for August 2006, and pathological examination showed non- CMV yielded a negative result in the 10th week. -

IHC) Outreach Services

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Outreach Services Note t ype of fixative used if not neutral buffered f ormalin. Note t ype of tissue/specim en Unless specified otherwise, positive and negative controls react satisfactoril y. Antibody Classif ications: – IVD (In Vitro Diagnosis) – No disclaimer required. – ASR (Anal yte Specific Reagent) – m ust use a disclaimer on the report (See Belo w) ASR required disclaimer T his test was developed a nd its perform ance characteristics determ ined b y Marshf ield Labs. It has not been cleared or approved b y th e U.S. Food and Drug Adm inistration. T he FDA has determ ined that such clearance or approval is not necessar y. T his test is used f or clinical purposes. It should not be regarded as investigational or f or research. T his laborator y is certif ied under the Clinical Laborator y Im provem ent Am endm ents (CLIA) as qualified to perf orm high-complexity testing. Available Chrom ogen – All m ark ers have been validated with 3,3’-Diam inobenzidine T etrah ydrochloride (DAB) which results in a bro wn/black precipitate. DAB is the routine chrom ogen. In addition, som e m ark ers have also been validated using the Fast Red (RED), which results in a re d precipitate. If available wit h both chrom ogens and one is not selected, the def ault will be t he DAB chrom ogen. Antibod y Common Applications Staining Characteristics/Cla ssification If Other Than IVD Actin (muscle specific) Smooth, skeletal & cardiac muscle Cytoplasmic Actin (smooth muscle) Smooth muscle and myoepithelial cells Cytoplasmic and membrane Adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) Pituitary neoplasms Cytoplasmic Alpha-1-Fetoprotein (AFP) Hepatoma, germ cell tumors Cytoplasmic ALK Protein ALK1 positive lymphomas Cytoplasmic and/or nuclear Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Demonstrates A-1-AT in liver Cytoplasmic (A-1-AT) Bcl-2 Oncoprotein Follicular lymphoma and soft tissue Cytoplasmic tumors Bcl-6 Follicular lymphoma Nuclear Ber-EP4, Epithelial Antigen Adenocarcinoma vs. -

Immunohistochemistry Immunohistochemistry

!"#$%&'"()(*+$(,$-#)&.(-&/$ 0--1.("23'(4"#-23'5+$$ 65.&17$7#$)&$8(14"&57295#$:;<$=";$ >+(.<$85&.4#$ Immunohistochemistry Immunohistochemistry It’s all about chosing the adapted anbody(ies) Immunohistochemistry It’s all about chosing the adapted anbody(ies) for the selected task(s) AnAbodies • « Melanocyc » anbodies – S100 – MelanA – HMB45 – PNL2 – MiTF Specificity vs Sensivity – SOX10 – … • « Anomaly-specific » anbodies – BRAF V600E – NRAS Q61R – ALK – ROS1 – NTRK1 – MET – P16 – BAP1 – PDL1 – … • Other anbodies – D2-40 – CD68 HMB45 – … AnAbodies • « Melanocyc » anbodies – S100 – MelanA – HMB45 – PNL2 – MiTF – SOX10 – … • « Anomaly-specific » anbodies – BRAF V600E – NRAS Q61R – ALK – ROS1 – NTRK1 – MET – P16 – BAP1 – PDL1 – … • Other anbodies – D2-40 – CD68 NTRK1 – … AnAbodies • « Melanocyc » anbodies – S100 – MelanA – HMB45 – PNL2 – MiTF – SOX10 – … • « Anomaly-specific » anbodies – BRAF V600E – NRAS Q61R – ALK – ROS1 – NTRK1 – MET – P16 – BAP1 – PDL1 – … • Other anbodies (DD mainly) – D2-40 – CD68 – … Why perform IHC? • Confirm melanocyc lineage • Visualize the melanocytes • Benign vs Malignant • Molecular characterizaon A. Confirm melanocyc lineage • Unpigmented dermal or ulcerated tumor (No recognizable junconal melanocytes) • Unpigmented metastases • Desmoplasc melanoma A1. Confirm melanocyc lineage Unpigmented dermal or ulcerated tumor M, 65 Back 6Ha$[(.T5-$-#)&.(4+A4$)2.#&*#$ b.%2*-#.'#7$7#5-&)$(5$1)4#5&'#7$'1-(5$$ b.%2*-#.'#7$.#3'$(,$#%2'"#)2(27$4#))3$ A1. Confirm melanocyc lineage Unpigmented dermal or ulcerated tumor S100 Protein 6Ha$[(.T5-$-#)&.(4+A4$)2.#&*#$ -

Pathology and Pathogenesis of SARS-Cov-2 Associated with Fatal Coronavirus Disease, United States Roosecelis B

Pathology and Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with Fatal Coronavirus Disease, United States Roosecelis B. Martines,1 Jana M. Ritter,1 Eduard Matkovic, Joy Gary, Brigid C. Bollweg, Hannah Bullock, Cynthia S. Goldsmith, Luciana Silva-Flannery, Josilene N. Seixas, Sarah Reagan-Steiner, Timothy Uyeki, Amy Denison, Julu Bhatnagar, Wun-Ju Shieh, Sherif R. Zaki; COVID-19 Pathology Working Group2 An ongoing pandemic of coronavirus disease (CO- United States; since then, all 50 US states, District of VID-19) is caused by infection with severe acute respi- Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, Northern Mariana Is- ratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Charac- lands, and US Virgin Islands have confirmed cases of terization of the histopathology and cellular localization COVID-19 (2–4). of SARS-CoV-2 in the tissues of patients with fatal CO- Coronaviruses are enveloped, positive-strand- VID-19 is critical to further understand its pathogenesis ed RNA viruses that infect many animals; human- and transmission and for public health prevention mea- adapted viruses likely are introduced through zoo- sures. We report clinicopathologic, immunohistochemi- notic transmission from animal reservoirs (5,6). Most cal, and electron microscopic findings in tissues from known human coronaviruses are associated with 8 fatal laboratory-confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 in- mild upper respiratory illness. SARS-CoV-2 belongs fection in the United States. All cases except 1 were in to the group of betacoronaviruses that includes severe residents of long-term care facilities. In these patients, SARS-CoV-2 infected epithelium of the upper and lower acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) airways with diffuse alveolar damage as the predominant and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus pulmonary pathology. -

Clinical Pathology, Immunopathology and Advanced Vaccine Technology in Bovine Theileriosis: a Review

pathogens Review Clinical Pathology, Immunopathology and Advanced Vaccine Technology in Bovine Theileriosis: A Review Onyinyechukwu Ada Agina 1,2,* , Mohd Rosly Shaari 3, Nur Mahiza Md Isa 1, Mokrish Ajat 4, Mohd Zamri-Saad 5 and Hazilawati Hamzah 1,* 1 Department of Veterinary Pathology and Microbiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Malaysia; [email protected] 2 Department of Veterinary Pathology and Microbiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Nigeria Nsukka, Nsukka 410001, Nigeria 3 Animal Science Research Centre, Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute, Headquarters, Serdang 43400, Malaysia; [email protected] 4 Department of Veterinary Pre-clinical sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Malaysia; [email protected] 5 Research Centre for Ruminant Diseases, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (O.A.A.); [email protected] (H.H.); Tel.: +60-11-352-01215 (O.A.A.); +60-19-284-6897 (H.H.) Received: 2 May 2020; Accepted: 16 July 2020; Published: 25 August 2020 Abstract: Theileriosis is a blood piroplasmic disease that adversely affects the livestock industry, especially in tropical and sub-tropical countries. It is caused by haemoprotozoan of the Theileria genus, transmitted by hard ticks and which possesses a complex life cycle. The clinical course of the disease ranges from benign to lethal, but subclinical infections can occur depending on the infecting Theileria species. The main clinical and clinicopathological manifestations of acute disease include fever, lymphadenopathy, anorexia and severe loss of condition, conjunctivitis, and pale mucous membranes that are associated with Theileria-induced immune-mediated haemolytic anaemia and/or non-regenerative anaemia. -

Immunohistochemistry (Ihc), Special Stains (Ss), & Cish Requisition

2119 E. 93rd / L15 Cleveland, OH 44106 IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY (IHC), 216.444.5755 or 800.628.6816 SPECIAL STAINS (SS), & CISH REQUISITION <<FORM_ID>> PATIENT INFORMATION (PLEASE PRINT IN BLACK INK) CLIENT INFORMATION ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Last Name First MI ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Address Birth Date Sex ¨ M ¨ F ___________________________________________________________________________________________ City SS # ___________________________________________________________________________________________ State Zip Home Phone ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Hospital/Physician Office atientP ID # Accession # ORDERING PHYSICIAN CONTACT MEDICAL NECESSITY NOTICE: When ordering tests for which Medicare reimbursement will be sought, physicians (or other individuals authorized by law to order tests) should only order tests that are medically necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of a patient, rather than for screening purposes. __________________________________________________________ Physician Name INSURANCE BILLING INFORMATION (PLEASE ATTACH CARD OR PRINT IN BLACK INK) BILL TO: ¨ Client/Institution ¨ Medicare ¨ Insurance (Complete insurance information below) ¨ Patient __________________________________________________________ PATIENT STATUS: ¨ Inpatient ¨ Outpatient ¨ Non-Hospital Patient Hospital discharge date: ______/______/______ Physician NPI# -

APPLICATION NOTE Anti-Fluortag Antibodies Enable

APPLICATION NOTE Anti-FluorTag Antibodies Enable Immunohistochemistry with Flow Cytometry Antibodies Yves Konigshofer, PhD, Alice Ku, Farol L. Tomson, PhD and Seth B. Harkins, PhD INTRODUCTION Figure 1 compares the sensitivity of fluorescence microscopy to immunohistochemistry. Sections of a mouse spleen were The KPL anti-FluorTag antibodies are a set of goat-derived first stained for dendritic cells using different concentrations polyclonal antibodies that can be used to detect Fluorescein of a FITC-labeled anti-CD11c antibody and then imaged with (FITC)-, Phycoerythrin (PE)-, Allophycocyanin (APC)- and a fluorescence microscope. Afterwards, HRP-labeled anti-FITC Peridinin Chlorophyll (PerCP)-labeled antibodies. They are and TrueBlue™ substrate were used to detect the FITC-labeled available unconjugated, as Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) antibodies. At 93 ng/ml, background signals from autofluo- conjugates and as High Potency Alkaline Phosphatase rescence began to exceed the specific signal and at 20 ng/ml, (ReserveAP™) conjugates. FITC-, PE-, APC- and PerCP- very little FITC fluorescence was visible above background. labeled antibodies are used in flow cytometry. These fluores- However, the dendritic cells could still be detected with the cent tags are chosen due to their brightness and compatibility anti-FITC antibody in conjunction with TrueBlue peroxidase with lasers commonly found on flow cytometers. While flow stain. cytometry is very effective at determining what cells express a given protein at a given level, it provides no information about where those cells are located in relation to one another. For this, microscopy-based immunohistochemistry (IHC) tech- niques are frequently required. Ideally, this should not require the purchase and optimization of an entirely new set of pri- mary antibodies. -

Overview of Pathology and Its Related Disciplines - Soheir Mahmoud Mahfouz

MEDICAL SCIENCES – Vol.I -Overview of Pathology and its Related Disciplines - Soheir Mahmoud Mahfouz OVERVIEW OF PATHOLOGY AND ITS RELATED DISCIPLINES Soheir Mahmoud Mahfouz Cairo University, Kasr El Ainy Hospital, Egypt Keywords: Pathology, Pathology disciplines, Pathology techniques, Ancillary diagnostic methods, General Pathology, Special Pathology Contents 1. Introduction 1.1 Pathology coverage 1.1.1 Etiology and Pathogenesis of a Disease 1.1.2 Manifestations of Disease (Lesions) 1.1.3 Phases Of A Disease Process (Course) 1.2 Physician’s approach to patient 1.3 Types of pathologists and affiliated specialties 1.4 Role of pathologist 2. Pathology and its related disciplines 2.1 Cytology 2.1.1 Cytology Samples 2.1.2 Technical Aspects 2.1.3 Examination of Sample and Diagnosis 3. Pathology techniques and ancillary diagnostic methods 3.1 Macroscopic pathology 3.2 Light Microscopy 3.3 Polarizing light microscopy 3.4 Electron microscopy (EM) 3.5 Confocal Microscopy 3.6 Frozen section 3.7 Cyto/histochemistry 3.8 Immunocyto/histochemical methods 3.9 Molecular and genetic methods of diagnosis 3.10 Quantitative methods 4. Types of tests used in pathology 4.1 DiagnosticUNESCO tests – EOLSS 4.2 Quantitative tests 4.3 Prognostic tests 5. The scope of SAMPLEpathology & its main divisions CHAPTERS 6. Conclusions Glossary Bibliography Biographical sketch Summary Pathology is the science of disease. It deals with deviations from normal body function and ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) MEDICAL SCIENCES – Vol.I -Overview of Pathology and its Related Disciplines - Soheir Mahmoud Mahfouz structure. Many disciplines are involved in the study of disease, as it is necessary to understand the complex causes and effects of various disorders that affect the organs and body as a whole. -

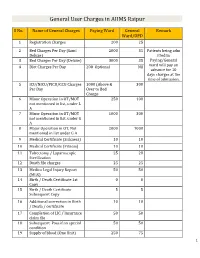

General User Charges in AIIMS Raipur

General User Charges in AIIMS Raipur S No. Name of General Charges Paying Ward General Remark Ward/OPD 1 Registration Charges 200 25 2 Bed Charges Per Day (Sami 2000 35 Patients being adm Deluxe) itted in 3 Bed Charges Per Day (Deluxe) 3000 35 Paying/General 4 Diet Charges Per Day 200 Optional Nil ward will pay an advance for 10 days charges at the time of admission. 5 ICU/NICU/PICU/CCU Charges 1000 (Above & 300 Per Day Over to Bed Charge 6 Minor Operation in OT/MOT 250 100 not mentioned in list, under L A 7 Minor Operation in OT/MOT 1000 300 not mentioned in list, under G A 8 Major Operation in OT, Not 2000 1000 mentioned in list under G A 9 Medical Certificate (Sickness) 10 10 10 Medical Certificate (Fitness) 10 10 11 Tubectomy / Laparoscopic 25 20 Sterilization 12 Death file charges 25 25 13 Medico Legal Injury Report 50 50 (MLR) 14 Birth / Death Certificate 1st 0 0 Copy 15 Birth / Death Certificate 5 5 Subsequent Copy 16 Additional correction in Birth 10 10 / Death / certificate 17 Completion of LIC / Insurance 50 50 claim file 18 Subsequent Pass if on special 50 50 condition 19 Supply of blood (One Unit) 250 75 1 20 Medical Board Certificate 500 500 On Special Case User Charges for Investigations in AIIMS Raipur S No. Name of Investigations Paying General Remark Ward Ward/OPD Anaesthsia 1 ABG 75 50 2 ABG ALONGWITH 150 100 ELECTROLYTES(NA+,K+)(Na,K) 3 ONLY ELECTROLYTES(Na+,K+,Cl,Ca+) 75 50 4 ONLY CALCIUM 50 25 5 GLUCOSE 25 20 6 LACTATE 25 20 7 UREA. -

Practice Parameter for the Diagnosis and Management of Primary Immunodeficiency

Practice parameter Practice parameter for the diagnosis and management of primary immunodeficiency Francisco A. Bonilla, MD, PhD, David A. Khan, MD, Zuhair K. Ballas, MD, Javier Chinen, MD, PhD, Michael M. Frank, MD, Joyce T. Hsu, MD, Michael Keller, MD, Lisa J. Kobrynski, MD, Hirsh D. Komarow, MD, Bruce Mazer, MD, Robert P. Nelson, Jr, MD, Jordan S. Orange, MD, PhD, John M. Routes, MD, William T. Shearer, MD, PhD, Ricardo U. Sorensen, MD, James W. Verbsky, MD, PhD, David I. Bernstein, MD, Joann Blessing-Moore, MD, David Lang, MD, Richard A. Nicklas, MD, John Oppenheimer, MD, Jay M. Portnoy, MD, Christopher R. Randolph, MD, Diane Schuller, MD, Sheldon L. Spector, MD, Stephen Tilles, MD, Dana Wallace, MD Chief Editor: Francisco A. Bonilla, MD, PhD Co-Editor: David A. Khan, MD Members of the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters: David I. Bernstein, MD, Joann Blessing-Moore, MD, David Khan, MD, David Lang, MD, Richard A. Nicklas, MD, John Oppenheimer, MD, Jay M. Portnoy, MD, Christopher R. Randolph, MD, Diane Schuller, MD, Sheldon L. Spector, MD, Stephen Tilles, MD, Dana Wallace, MD Primary Immunodeficiency Workgroup: Chairman: Francisco A. Bonilla, MD, PhD Members: Zuhair K. Ballas, MD, Javier Chinen, MD, PhD, Michael M. Frank, MD, Joyce T. Hsu, MD, Michael Keller, MD, Lisa J. Kobrynski, MD, Hirsh D. Komarow, MD, Bruce Mazer, MD, Robert P. Nelson, Jr, MD, Jordan S. Orange, MD, PhD, John M. Routes, MD, William T. Shearer, MD, PhD, Ricardo U. Sorensen, MD, James W. Verbsky, MD, PhD GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Aerocrine; has received payment for lectures from Genentech/ These parameters were developed by the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters, representing Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck; and has received research support from Genentech/ the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; the American College of Novartis and Merck. -

Immunohistochemistry in the Diagnosis of Cutaneous Infections

Immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of cutaneous infections Ana María Molina Ruiz Thesis for the fulfillment of the PhD degree in Medical Science UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE MEDICINA Department of Internal Medicine TESIS DOCTORAL Immunohistochemistry in the Diagnosis of Cutaneous Viral and Bacterial Infections AUTHOR: Ana María Molina Ruiz DIRECTOR: Luis Requena Caballero Department of Dermatology, Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Department of Internal Medicine, Universidad Autónoma, Madrid Memoria para optar al grado de Doctor en Medicina con Mención Internacional al Título. Tesis presentada como compendio de publicaciones. UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE MEDICINA Departamento de Medicina Interna D. Luis Requena Caballero, Catedrático de Dermatología del Departamento de Medicina de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. CERTIFICA: Que Dña. Ana María Molina Ruiz ha realizado bajo mi dirección el trabajo “Immunohistochemistry in the Diagnosis of Cutaneous Viral and Bacterial Infections“ que a mi juicio reúne las condiciones para optar al Grado de Doctor. Para que así conste, firmo el presente certificado en Madrid a 3 de septiembre del año dos mil catorce. Vº Bº Director de la Tesis Doctoral Profesor Luis Requena Caballero Catedrático de Dermatología Departamento de Medicina, Facultad de Medicina Universidad Autónoma de Madrid DERMATOPATHOLOGIE FRIEDRICHSHAFEN BODENSEE Dermatopathologische Gemeinschaftspraxis PD Dr. med. Heinz Kutzner, Dermatologe Postfach 16 46, 88006 Friedrichshafen Dr. med. Arno Rütten, Dermatologe Prof. Dr. med. Thomas Mentzel, Pathologe Dr. med. Markus Hantschke, Dermatologe Dr. med. Bruno Paredes, Dermatologe, Pathologe Dr. med. Leo Schärer, Dermatologe Postfach 16 46, 88006 Friedrichshafen Siemensstr. 6/1, 88048 Friedrichshafen May 28, 2014 To Whom it May Concern Gentlemen, I have read Dr.