Preview Jörg Widmann's New Flute Concerto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Preview Notes • Week Two • Persons Auditorium

2019 Preview Notes • Week Two • Persons Auditorium Saturday, July 20 at 8:00pm Flute Quartet in D Major, K. 285 (1777-78) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Born January 27, 1756 • Died December 5, 1791 Duration: approx. 15 minutes Last Marlboro performance: 2011 When Mozart was just a few years younger than the junior participants in this group, he travelled throughout Europe with his mother in search of employment. While in Mannheim on his way to Paris, he met a Dutch merchant named Willem van Britten Dejong who happened to be an amateur flute player. Dejong, who had made his fortune in India, was happy to commission three concertos and three quartets for his instrument. Mozart, who needed the funds, was happy to accept. However, he only completed the quartets and two concertos (one a transcription of a previously-composed oboe concerto) by the time he left Mannheim. What he did write, though, charmingly showcases the flute. In this quartet, that instrument takes the lead throughout a buoyant Allegro beginning, a delicate Adagio accompanied by sparkling plucking from the strings, and a boisterous but well-balanced Rondo conclusion. Participants: Giorgio Consolati, flute; Hiroko Yajima, violin; Jordan Bak, viola; Alexander Hersh, cello Octet (2004) Jörg Widmann Born June 19, 1973 • In residence 2008, 2019 Duration: approx. 30 minutes Marlboro Premiere Though Widmann’s Octet features frequent microtones, he admits that the piece is “almost throughout, a tonal piece,” which was “risky to write in 2004.” The instrumentation suggests a clear connection to Schubert’s genre-making octet, and the piece’s central third movement, which is titled Lied ohne Worte, is a plangent nod to the composer who wrote so many Lieder over the course of his short life. -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

Program Notes Quartet No

Ariel Quartet Gershon Gerchikov, violin Alexandra Kazovsky, violin Jan Grüning, viola Amit Even-Tov, cello with Ilya Shterenberg, clarinet Quartet No. 8 in C minor, Op. 110 Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-75) Largo Allegro molto Allegretto Largo Largo Clarinet Quintet in A major, K. 581 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-91) Allegro Larghetto Menuetto Allegretto con variazioni Clarinet Quintet in B-Flat Major, Op. 34 Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826) Rondo: Allegro giojoso - INTERMISSION - Quartet in D minor, D. 810, “Death and the Maiden” Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Allegro Andante con moto Scherzo. Allegro molto Presto Ariel Quartet is represented by MKI Artists; One Lawson Lane, Suite 320, Burlington, VT 05401. Recordings: Avie Records www.arielquartet.com www.sacms.org Program Notes Quartet No. 8 in C minor, Op. 110 Dmitri Shostakovich By 1960 the ‘Thaw’ following Stalin’s death had improved the outward circumstances of Shostakovich’s life, and he was honored at home and allowed to travel abroad to perform and receive additional honors. The price was a requirement that he perform many duties for the official music establishment. In April 1960, at the personal invitation of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, Shostakovich was elected head of the Russian Composers’ Union. He was also pressured to join the Communist Party, a step he had avoided during all his earlier years of torment. he did this without telling his family and friends, and when it became public the intense shame of his capitulation led to a nervous breakdown in June 1960. “I’ve been a whore, I am and always will be a whore,” he told his old friend Isaak Glikman with tears streaming down his face. -

Boston Symphony Chamber Players 50Th Anniversary Season 2013-2014

Boston Symphony Chamber Players 50th anniversary season 2013-2014 jordan hall at the new england conservatory october 13 january 12 february 9 april 6 BOSTON SYMPHONY CHAMBER PLAYERS Sunday, January 12, 2014, at Jordan Hall at New England Conservatory TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Welcome 4 “The Boston Symphony Chamber Players: For Fifty Years, Champions of Chamber Music,” by Richard Dyer 6 From the Players 10 Today’s Program Notes on the Program 11 Aaron Copland 13 Irving Fine 14 Wolfgang Amadè Mozart 15 Johannes Brahms Artists 16 Boston Symphony Chamber Players 17 Gilbert Kalish 19 The Boston Symphony Chamber Players: A Discography COVER PHOTO (top) Founding members of the Boston Symphony Chamber Players, 1964: (seated, left to right) Joseph Silverstein, violin; Burton Fine, viola; Jules Eskin, cello; Doriot Anthony Dwyer, flute; Ralph Gomberg, oboe; Gino Cioffi, clarinet; Sherman Walt, bassoon; (standing, left to right) Georges Moleux, double bass; Everett Firth, timpani; Roger Voisin, trumpet; William Gibson, tombone; James Stagliano, horn (BSO Archives) COVER PHOTO (bottom) The Boston Symphony Chamber Players in 2012 at Jordan Hall: (seated in front, from left): Malcolm Lowe, violin; Haldan Martinson, violin; Jules Eskin, cello; Steven Ansell, viola; (rear, from left) Elizabeth Rowe, flute; John Ferrillo, oboe; William R. Hudgins, clarinet; Richard Svoboda, bassoon; James Sommerville, horn; Edwin Barker, bass (photo by Stu Rosner) ADDITIONAL PHOTO CREDITS Individual Chamber Players portraits pages 6, 7, 8, and-9 by Tom Kates, except Elizabeth Rowe (page 8) and Richard Svoboda (page 9) by Michael J. Lutch. Boston Symphony Chamber Players photo on page 16 by Michael J. Lutch. -

Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: a Performance Guide

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2016 Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: A Performance Guide Erin Elizabeth Vander Wyst University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Fine Arts Commons, Music Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Vander Wyst, Erin Elizabeth, "Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: A Performance Guide" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2754. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/9112202 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KIMMO HAKOLA’S DIAMOND STREET AND LOCO: A PERFORMANCE GUIDE By Erin Elizabeth Vander Wyst Bachelor of Fine Arts University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 2007 Master of Music in Performance University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 2009 -

Guide to Repertoire

Guide to Repertoire The chamber music repertoire is both wonderful and almost endless. Some have better grips on it than others, but all who are responsible for what the public hears need to know the landscape of the art form in an overall way, with at least a basic awareness of its details. At the end of the day, it is the music itself that is the substance of the work of both the performer and presenter. Knowing the basics of the repertoire will empower anyone who presents concerts. Here is a run-down of the meat-and-potatoes of the chamber literature, organized by instrumentation, with some historical context. Chamber music ensembles can be most simple divided into five groups: those with piano, those with strings, wind ensembles, mixed ensembles (winds plus strings and sometimes piano), and piano ensembles. Note: The listings below barely scratch the surface of repertoire available for all types of ensembles. The Major Ensembles with Piano The Duo Sonata (piano with one violin, viola, cello or wind instrument) Duo repertoire is generally categorized as either a true duo sonata (solo instrument and piano are equal partners) or as a soloist and accompanist ensemble. For our purposes here we are only discussing the former. Duo sonatas have existed since the Baroque era, and Johann Sebastian Bach has many examples, all with “continuo” accompaniment that comprises full partnership. His violin sonatas, especially, are treasures, and can be performed equally effectively with harpsichord, fortepiano or modern piano. Haydn continued to develop the genre; Mozart wrote an enormous number of violin sonatas (mostly for himself to play as he was a professional-level violinist as well). -

Brahms Clarinet Quintet Op

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op.115 (1891) Allegro Adagio Andantino - Presto non assai, ma con sentimento Con moto By March 1891 Brahms' creative impetus appeared to have faded away. He had composed nothing for more than a year and had completed his will. But then, visiting Meiningen, the conductor of the court orchestra drew Brahms' attention to the playing of their erstwhile violinist, now principal clarinettist, Richard Mühlfeld (1856-1907), who performed privately for Brahms. As Anton Stadler had previously inspired Mozart, so now Mühlfeld inspired Brahms. There rapidly followed four wonderful chamber pieces: a Trio for piano, clarinet and cello Op 114, today's Quintet Op 115, and two clarinet and piano Sonatas Op 120. In the hundred years since Mozart wrote his clarinet quintet, the instrument had evolved into something akin to the modern “Boehm” clarinet. Its larger number of keys, and consequently simpler fingering, made rapid chromatic playing easier than was possible on the much simpler clarinets used, albeit to great effect, by Stadler. The opening B minor theme on the two violins provides much of the basic material for the work. The clarinet then enters with a rising arpeggio just as in Mozart's quintet, and leads us to a contrasting staccato motif with rapid accompanying triplets that are tossed between the instruments. The Adagio in B major has a slow melody in the clarinet accompanied by a Brahms trademark complex rhythm superimposing triplets with syncopated duplets in the strings. The two illustrated themes are then combined in the turbulent B minor central section of the movement with gymnastic flourishes from the clarinet. -

Jörg Widmann

THE 2019–2020 RICHARD AND BARBARA DEBS COMPOSER’S CHAIR Jörg Widmann Marco Borggreve Marco Composer, clarinetist, and conductor Jörg Widmann has been appointed to the Richard and Barbara Debs Composer’s Chair for the 2019–2020 season. Mr. Widmann’s captivating and powerfully visceral music has won him numerous high-profile commissions and countless performances from soloists, chamber ensembles, and major orchestras around the world. A much sought- after virtuoso clarinetist and dynamic conductor, he has performed his own works—as well as works by other composers—with Daniel Barenboim, Mitsuko Uchida, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, and a host of other great artists. Mr. Widmann’s residency showcases his musical versatility and imaginative vision with his powerful orchestral works performed by The Cleveland Orchestra, Munich Philharmonic, Mahler Chamber Orchestra, and The MET Orchestra. The series also recognizes the striking originality in his chamber music with an all-star ensemble headlined by violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter, who gives the New York premiere of his new work for string quartet. He displays his formidable skills as a clarinetist, playing his own music as well as works by Schumann and Mozart in a trio with violist Tabea Zimmermann and pianist Dénes Várjon. He does triple duty with the Irish Chamber Orchestra, conducting his own music and playing the clarinet, and with the International Contemporary Ensemble in a program devoted to his works. As part of his residency, he returns to his alma mater to conduct the Juilliard Orchestra at Alice Tully Hall. The series additionally features two lectures in which he discusses dissonance and beauty, as well as Beethoven’s lasting impact. -

A Semiotic Approach to the Clarinet Quintet of Johannes Brahms By

A Semiotic Approach to the Clarinet Quintet of Johannes Brahms by Roberto Mikael Abragan de Guzman A thesis submitted to the Moores School of Music, Kathrine G. McGovern College of the Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance Chair of Committee: Timothy Koozin Committee Member: Chester Rowell Committee Member: Rob Smith Committee Member: Dan Gelok University of Houston May 2021 Copyright 2021, Roberto Mikael Abragan de Guzman Abstract This paper will provide a comprehensive look at Brahms’s clarinet quintet by providing a semiotic approach to the musical analysis. The quintet contains deformations regarding its form, according to James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy’s study of sonata cycle and sonata form. Furthermore, musical gestures introduced in the initial movement occur sporadically throughout the rest of the piece, creating connections between movements through their reoccurrence. Normative and non-normative events in the form of individual movements and the work as a whole give rise to oppositions that shape elements of conflict in musical narrative. Eero Tarasti’s semiotic analysis along with James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy’s sonata theory and Edward Klorman’s idea of social interaction in the music will provide methodological approaches in examining the Brahms’s clarinet quintet. The combination of these approaches helps in identifying a narrative that spans the entirety of the piece. Structural points in musical narrative are identified by applying concepts associated with sonata form and sonata cycle, while plot developments in the narrative are correlated with recurring motives and themes. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... -

Clarinets - the Tools of Expression

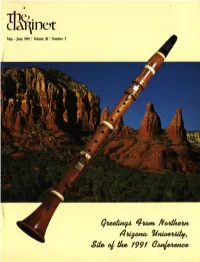

May - June 1991 Volume 18 Number 3 qudinv, It. wiliteilli, 4440ita. Site tile 1991 conk. Buffet Clarinets - The Tools of Expression he tools of expression allow the artist to communicate the essence of the creative spirit. As an artist, you require the proper tools to fully express your creative spirit. The artists of Buffet Crampon have understood this since 1825 — which is why to this day their clarinets, hand crafted in the finest French tradition, continue to breathe life into the musical soul. Buffet Elite A and Bb clarinets are created to elevate the art of expression to new splendor. Their unique thin wall construc- tion and state of the art design permit a resonance and response that open new frontiers of creativity for the accomplished soloist. The perfect marriage of French tradition and 20th century technology, the Buffet Elites will enhance your creative spirit in ways you never thought possible. Boosey & Hawkes/Buffet Crampon Inc. 1925 Enterprise Court, Libertyville, Illinois 60048 708. 816. 2500 the claainet Volume 18, Number 3 May - June 1991 Features INDEX OF ADVERTISERS Albert Alphin 22 THE ELECTRONIC TUNER by Robert Listokin 18 Bay-Gale Woodwind Products 4 HOW TO CHOOSE AN ARTIST CLARINET Boosey and Hawkes/Buffet inside front cover by Jack Snavely 22 Clarinet and Saxophone Society of Great Britain 42 THE CLARINET SECTION OF THE UNITED STATES Clark Woodwinds 51 AIR FORCE ACADEMY BAND 24 Rich Corpolongo 33 THE LYONS C CLAR1NET—A REVIEW by Colin Lawson Crystal Records 23 26 Cygnet 34 FESTIVAL DIRECTOR'S MESSAGE by Charles Aurand 28 Dantalian, Inc 5 DEG Products, Inc. -

(Of(R) Viola) and Piano Op

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: November 18, 2004 I, Kyung ju Lee _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Viola Performance It is entitled: An analysis and comparison of the clarinet and viola versions of the Two sonatas for clarinet (or Viola) And piano Op.120 by Johannes Brahms. This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Catharine Carroll Lee Fiser Steven Cohen 2 AN ANALYSIS AND COMPARISON OF THE CLARINET AND VIOLA VERSION OF THE TWO SONATAS FOR CLARINET (OR VIOLA) AND PIANO OP. 120 BY JOHANNES BRAHMS. A document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2004 by Kyungju Lee B.M., Yeungnam University, 1996 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2000 A.D., University of Cincinnati, 2002 Committee Chair: Catharine Carroll, D.M.A. 2 3 ABSTRACT Johannes Brahms was one of the first composers to appreciate fully the viola’s potential, allowing the instrument a chance to shine in his chamber music. Although Brahms’ Two Sonatas in f-minor and E-flat major, Op.120, were originally written for clarinet and piano, they are also greatly loved in the viola repertoire. Upon examination of the clarinet and viola versions of the sonatas, Brahms seems to have been keenly aware of the potential of each instrument. He intentionally sought different effects from these two instruments by composing two different versions. -

Jörg Widmann Is One of the Most Versatile and Intriguing Artists of His Generation

Clarinetist, composer and conductor Jörg Widmann is one of the most versatile and intriguing artists of his generation. As Carnegie Hall’s 2019/20 Richard and Barbara Debs Composer Chair his work will be focused throughout the season. Further performances see him appear in all aspects as clarinetist, composer and conductor as artist in residence at WDR Sinfonieorchester, at Palau de la Música Barcelona and at Bergen International Festival. Chamber music performances will see him in concerts with long-standing chamber music partners such as Andras Schiff, Daniel Barenboim, Mitsuko Uchida, Tabea Zimmermann, Antoine Tamestit and the Hagen Quartet at the Schubertiade Schwarzenberg, Salzburg Festival, Carnegie Hall New York and Wiener Konzerthaus amongst others. Continuing his intense activities as a conductor, Jörg Widmann performs this season with the Ensemble Kanazawa, WDR Sinfonieorchester, Swedish Chamber Orchestra and Hessisches Staatsorchester Wiesbaden. In November 2019 he will lead the Irish Jörg Chamber Orchestra as their Principal Conductor on tour through the US and in concerts throughout Europe. Widmann Widmann studied clarinet with Gerd Starke in Munich and Charles Neidich at the Juilliard School in New York. He performs regularly with renowned orchestras, such as Curriculum vitae Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Orchestra National de France, Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, National Symphony Orchestra Washington, Orchestre symphonique de Montréal, Vienna (long version) Philharmonic Orchestra, Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra and Toronto Symphony Orchestra. He collaborates with conductors such as Daniel Barenboim, Christoph Eschenbach and Christoph von Dohnányi. Widmann gave the world premiere of Mark Andre’s Clarinet Concerto über at the Donaueschinger Musiktage 2015. Other clarinet concerti dedicated to and written for him include Wolfgang Rihm’s Musik für Klarinette und Orchester (1999) and Aribert Reimann’s Cantus (2006).