SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES the Representation of George

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penang Page 1 Area Location State Outskirt ODA 10990 Penang Yes

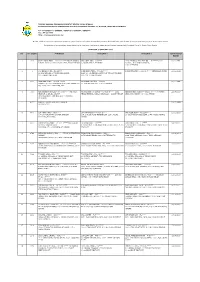

Penang Post Major code Area Location State Town Outskirt ODA Delivery Day Delivery Delivery Day - 1 to 2 Day - 1 to 7 - 3 to 4 working working working days days days 10990 Pulau Pinang - Beg berkunci Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 11000 Focus Heights Balik Pulau Penang Yes 11000 Jalan Pinang Nirai Balik Pulau Penang Yes 11000 Kampung Kuala Muda Balik Pulau Penang Yes 11000 Kebun Besar Balik Pulau Penang Yes 11000 Kuala Muda Balik Pulau Penang Yes 11000 Padang Kemunting Mk. E Balik Pulau Penang Yes 11000 Padang Kemunting Balik Pulau Penang Yes 10000 Bangunan Komtar Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10000 Jalan Gladstone Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10000 Jalan Magazine (No Genap) Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10000 Kompleks Tun Abdul Razak Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10000 Lebuh Tek Soon Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10000 Prangin Mall Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Argyll Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Ariffin Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Arratoon Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Bawasah Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Burma (1 - 237 & 2 - 184) Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Chow Thye Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Clove Hall Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Dato Koyah Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Dinding Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Gudwara Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Hutton Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Irawadi Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Khoo Sian Ewe Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Larut Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Nagore Pulau Pinang Penang Yes 10050 Jalan Pangkor Pulau Pinang Penang -

BKT DUMBAR NEWS.Pages

18/9/2016 OFFICIAL LAUNCHING OF BUKIT DUMBAR PUMPING STATION 2 Community Home > Metro > Community Tuesday, 20 September 2016 Southern Penang gets uninterrupted water supply CONTINUOUS good water supply to the Bayan Lepas Free Trade Zone, Penang International Airport and southern parts of Penang island is now better guaranteed following the commission of a new water pump station at Bukit Dumbar. Called BD2, it could pump up to 270 million litres of water per day (MLD) to serve 315,000 people living in the southern parts of the island. PBAPP senior chargeman Mohd Yusri Awang checking the reading of a pump at the newly opened Bukit Dumbar Pump Station 2 in Penang. Its service areas cover Gelugor, Batu Uban, Sungai Nibong, Bayan Baru, Relau, Sungai Ara, Batu Maung, Bayan Lepas, Permatang Damar Laut, Teluk Kumbar, Gertak Sanggul, Genting and Balik Pulau. Penang Water Supply Corporation Sdn Bhd (PBAPP) chief executive officer Datuk Jaseni Maidinsa said the RM11.9mil BD2 would complement the operations of the Bukit Dumbar Pump Station 1 (BD1) that had been in service since 1980. He said it would improve pumping efficiency of water from the Sungai Dua Water Treatment Plant on the mainland to southern areas of the island which were undergoing rapid socio-economic development. “Treated water from the Sungai Dua plant is delivered to Bukit Dumbar daily via twin submarine pipeline,” Jaseni said at the launching of BD2 on Sunday. He said BD2 would also reduce pumping costs to the Bukit Gedong Reservoir daily to support the treated water needs of Teluk Kumbar, Gertak Sanggul and Balik Pulau. -

Why Is Pronunciation So Difficult to Learn?

www.ccsenet.org/elt English Language Teaching Vol. 4, No. 3; September 2011 Why is Pronunciation So Difficult to Learn? Abbas Pourhossein Gilakjani (Corresponding author) School of Educational Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia 3A-05-06 N-Park Jalan Batu Uban 11700 Gelugor Pulau Pinang Malaysia Tel: 60-174-181-660 E-mail: [email protected] Mohammad Reza Ahmadi School of Educational Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia 3A-05-06 N-Park Alan Batu Uban 1700 Gelugor Pulau Pinang Malaysia Tel: 60-175-271-870 E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 8, 2011 Accepted: March 21, 2011 doi:10.5539/elt.v4n3p74 Abstract In many English language classrooms, teaching pronunciation is granted the least attention. When ESL teachers defend the poor pronunciation skills of their students, their arguments could either be described as a cop-out with respect to their inability to teach their students proper pronunciation or they could be regarded as taking a stand against linguistic influence. If we learn a second language in childhood, we learn to speak it fluently and without a ‘foreign accent’; if we learn in adulthood, it is very unlikely that we will attain a native accent. In this study, the researchers first review misconceptions about pronunciation, factors affecting the learning of pronunciation. Then, the needs of learners and suggestions for teaching pronunciation will be reviewed. Pronunciation has a positive effect on learning a second language and learners can gain the skills they need for effective communication in English. Keywords: Pronunciation, Learning, Teaching, Misconceptions, Factors, Needs, Suggestions 1. Introduction General observation suggests that it is those who start to learn English after their school years are most likely to have serious difficulties in acquiring intelligible pronunciation, with the degree of difficulty increasing markedly with age. -

Great New World Report V6

27 July 2019 Bangunan UAB, George Town SUMMARY REPORT 2 Executive Summary Executive Summary Gathering arts practitioners, art historians and Spanning a full day of presentations and stakeholders in Penang’s creative scene, the Great discussions on various aspects of Penang’s art New World: From Free Port to Heritage Site art history, the event was the first such Symposium symposium was held in July 2019 to piece together which took place at the state capital’s annual arts an overview of Penang art history. The Symposium festival, George Town Festival. Speakers comprising was organised by Penang Art District, Ruang artists and academics connected to Penang Kongsi, and Malaysia Design Archive with the presented a loosely chronological view on the intention to shed light on Penang’s past, present, development of visual and performing arts in and future in the realm of art. Penang society. Each set of presentations were followed by a conversation and a question and In Malaysia, discourse on art history beyond the answer session. capital city of Kuala Lumpur is relatively sparse, thus alienating significant cultural works and stories from the national narrative. George Town, situated on one of Malaysia’s best-known islands, and steeped in history and culture, was deemed the ideal place to generate such a discussion. Key takeaways from the Symposium are as follows: There is a vast amount of heritage narratives untapped across Penang state, with plenty of potential in places further away from the state capital of George Town. There is a necessity to review archive materials and offer alternative interpretations, as well as to excavate multiple, plausible interpretations rather than chase after one “true” narrative, given Penang’s diverse cultural influences. -

For Sale - Batu Uban, Gelugor, Penang

iProperty.com Malaysia Sdn Bhd Level 35, The Gardens South Tower, Mid Valley City, Lingkaran Syed Putra, 59200 Kuala Lumpur Tel: +603 6419 5166 | Fax: +603 6419 5167 For Sale - Batu Uban, Gelugor, Penang Reference No: 101582410 Tenure: Freehold Address: Pesiaran Batu Uban, Taman Occupancy: Vacant Century, Batu Uban, 11700, Furnishing: Partly furnished Penang Land Title: Residential State: Penang Property Title Type: Individual Property Type: Semi-detached House Facing Direction: North Asking Price: RM 1,800,000 Posted Date: 27/04/2021 Built-up Size: 3,400 Square Feet Property Features: Kitchen cabinet,Air Built-up Price: RM 529.41 per Square Feet conditioner,Bath tub,Garden Land Area Size: 2,000 Square Feet Name: Eiffel Huam Land Area Price: RM 900 per Square Feet Company: INTEREALTOR SDN. BHD. No. of Bedrooms: 5 Email: [email protected] No. of Bathrooms: 3 FOR SALE/RENT: *DOUBLE STOREY SEMI-D @ TAMAN CENTURY, PERSIARAN BATU UBAN* Land area 2000 sq ft Build area 3400 sq ft Partial furnished 5 bedrooms 3 bathrooms 2 car parks Rental RM2300 nego Selling price RM1.8M nego Features: - Well maintained unit - Facing North - Big compound - About 10-15 mins drive to super tanker wet market, Tesco extra, Lip Sin morning wet market. - Easy access to food court, bank, Queensbay malls, bus terminal, Penang Bridge, FIZ area, airport (Ref: LP/35/DEC/20) View to appreciate. Offers are welcome. Kindly contact Eiffel at 012-489 .... [More] View More Details On iProperty.com iProperty.com Malaysia Sdn Bhd Level 35, The Gardens South Tower, Mid Valley City, Lingkaran Syed Putra, 59200 Kuala Lumpur Tel: +603 6419 5166 | Fax: +603 6419 5167 For Sale - Batu Uban, Gelugor, Penang. -

Fax : 04-2613453 Http : // BIL NO

TABUNG AMANAH PINJAMAN PENUNTUT NEGERI PULAU PINANG PEJABAT SETIAUSAHA KERAJAAN NEGERI PULAU PINANG TINGKAT 25, KOMTAR, 10503 PULAU PINANG Tel : 04-6505541 / 6505599 / 6505165 / 6505391 / 6505627 Fax : 04-2613453 Http : //www.penang.gov.my Berikut adalah senarai nama peminjam-peminjam yang telah menyelesaikan keseluruhan pinjaman dan tidak lagi terikat dengan perjanjian pinjaman penuntut Negeri Pulau Pinang Pentadbiran ini mengucapkan terima kasih di atas komitmen tuan/puan di dalam menyelesaikan bayaran balik Pinjaman Penuntut Negeri Pulau Pinang SEHINGGA 31 JANUARI 2020 BIL NO AKAUN PEMINJAM PENJAMIN 1 PENJAMIN 2 TAHUN TAMAT BAYAR 1 371 QUAH LEONG HOOI – 62121707**** NO.14 LORONG ONG LOKE JOOI – 183**** TENG EE OO @ TENG EWE OO – 095**** 4, 6TH 12/07/1995 SUNGAI BATU 3, 11920 BAYAN LEPAS, PULAU PINANG. 6, SOLOK JONES, P PINANG AVENUE, RESERVOIR GARDEN , 11500 P PINANG 2 8 LAU PENG KHUEN – 51062707 KHOR BOON TEIK – 47081207**** CHOW PENG POY – 09110207**** MENINGGAL DUNIA 31/12/1995 62 LRG NANGKA 3, TAMAN DESA DAMAI, BLOK 100-2A MEWAH COURT, JLN TAN SRI TEH EWE 14000 BUKIT MERTAJAM LIM, 11600 PULAU PINANG 3 1111 SOO POOI HUNG – 66121407**** IVY KHOO GUAT KIM – 56**** - 22/07/1996 BLOCK 1 # 1-7-2, PUNCAK NUSA KELANA CONDO JLN 10 TMN GREENVIEW 1, 11600 P PINANG PJU 1A/48, 47200 PETALING JAYA 4 343 ROHANI BINTI KHALIB – 64010307**** NO 9 JLN MAHMUD BIN HJ. AHMAD – 41071305**** 1962, NOORDIN BIN HASHIM – 45120107**** 64 TAMAN 22/07/1997 JEJARUM 2, SEC BS 2 BUKIT TERAS JERNANG, BANGI, SELANGOR. - SUDAH PINDAH DESA JAYA, KEDAH, 08000 SG.PETANI SENTOSA, BUKIT SENTOSA, 48300 RAWANG, SELANGOR 5 8231 KHAIRIL TAHRIRI BIN ABDUL KHALIM – - - 16/03/1999 80022907**** 6 7700 LIM YONG HOOI – A345**** LIM YONG PENG – 74081402**** GOH KIEN SENG – 73112507**** 11/11/1999 104 18-A JALAN TAN SRI TEH, EWE LIM, 104 18-A JLN T.SRI TEH EWE LIM, 11600 PULAU 18-I JLN MUNSHI ABDULLAH, 10460 PULAU PINANG 11600 PULAU PINANG PINANG 7 6605 CHEAH KHING FOOK – 73061107**** NO. -

Persatuan Warisan Pulau Pinang Penang Heritage Trust Annual

Persatuan Warisan Pulau Pinang Penang Heritage Trust Registered Address: 26 Lebuh Gereja 10200, Pulau Pinang Annual Report 2013 26, Church Street, City of George Town, 10200 Penang, Malaysia Tel: 604-264 2631 Fax: 604-262 8421 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.pht.org.my 1 Annual General Meeting 2013 3.30 p.m., Sunday, 17 November 2013 Venue: Ren-I-Tang, 82-A Lebuh Penang (Penang Street) Agenda 1. To consider and approve: The Minutes of the PHT Annual General Meeting – 18 November 2012 st st The PHT Annual Report 1 October 2012– 31 October 2013 st The PHT Financial Report ending 31 December 2012 2. Election of Council Members (2014-2015) 3. Other Matters 2 Penang Heritage Trust President's Message Fifteen years ago, the Penang Heritage Trust initiated the process for George Town to be nominated to the UNESCO World Heritage list. At the time, we were the only established organisation concerned about Penang’s heritage. George Town was facing the repeal of Rent Control. We put much effort into explaining why heritage is important to Penang’s future. To draw attention to the situation, we registered George Town on the World Monuments Watch’s List of 100 Endangered Sites (twice on the biennial list, 2000-2004). After UNESCO listing in 2008, it seems that Penang’s heritage is now largely recognized by the state, the private sector, the people of Penang and tourists who snap away at our food and buildings and circulate the images around the world. We have succeeded in making heritage a buzz word in Penang. -

Technopolitics of Historic Preservation in Southeast Asian Chinatowns: Penang, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City

Technopolitics of Historic Preservation in Southeast Asian Chinatowns: Penang, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City By Napong Rugkhapan A dissertation suBmitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Urban and Regional Planning) In the University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Professor Martin J. Murray, Chair Associate Professor Scott D. CampBell Professor Linda L. Groat Associate Professor Allen D. Hicken ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without various individuals I have met along the journey. First and foremost, I would like to thank my excellent dissertation committee. The dissertation chair, Professor Martin J. Murray, has been nothing but supportive from day one. I thank Martin for his enthusiasm for comparative urBanism - the same enthusiasm that encouraged me to embark on one. In particular, I thank him for letting me experiment with my own thought, for letting me pursue the direction of my scholarly interest, and for Being patient with my attempt at comparative research. I thank Professor Linda Groat for always Being accessible, patient, and attentive to detail. Linda taught me the importance of systematic investigation, good organization, and clear writing. I thank Professor Scott D. Campbell for, since my first year in the program, all the inspiring intellectual conversations, for ‘ruBBing ideas against one another’, for refreshingly different angles into things I did not foresee. Scott reminds me of the need to always think Broadly aBout cities and theory. I thank Professor Allen D. Hicken for his constant support, insights on comparative research, vast knowledge on Thai politics. Elsewhere on campus, I thank Professor Emeritus Rudolf Mrazek, the first person to comment on my first academic writing. -

PENANG MUSEUMS, CULTURE and HISTORY Abu Talib Ahmad

Kajian Malaysia, Vol. 33, Supp. 2, 2015, 153–174 PENANG MUSEUMS, CULTURE AND HISTORY Abu Talib Ahmad School of Humanities, Universiti Sains Malaysia, MALAYSIA Email: [email protected] The essay studies museums in Penang, their culture displays and cultural contestation in a variety of museums. Penang is selected as case study due to the fine balance in population numbers between the Malays and the Chinese which is reflected in their cultural foregrounding in the Penang State Museum. This ethnic balance is also reflected by the multiethnic composition of the state museum board. Yet behind this façade one could detect the existence of culture contests. Such contests are also found within the different ethnic groups like the Peranakan and non-Peranakan Chinese or the Malays and the Indian-Muslims. This essay also examines visitor numbers and the attractiveness of the Penang Story. The essay is based on the scrutiny of museum exhibits, museum annual reports and conversations with former and present members of the State Museum Board. Keywords: Penang museums, State Museum Board, Penang Story, museum visitors, culture and history competition INTRODUCTION The phrase culture wars might have started in mid-19th century Germany but it came into wider usage since the 1960s in reference to the ideological polarisations among Americans into the liberal and conservative camps (Hunter, 1991; Luke, 2002). Although not as severe, such wars in Malaysia are manifested by the intense culture competition within and among museums due to the pervasive influence of ethnicity in various facets of the national life. As a result, museum foregrounding of culture and history have become contested (Matheson- Hooker, 2003: 1–11; Teo, 2010: 73–113; Abu Talib, 2008: 45–70; 2012; 2015). -

301 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

301 bus time schedule & line map 301 Jeti - Relau View In Website Mode The 301 bus line (Jeti - Relau) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Jeti - Relau: 5:45 AM - 11:30 PM (2) Relau - Jeti: 5:30 AM - 10:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 301 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 301 bus arriving. Direction: Jeti - Relau 301 bus Time Schedule 50 stops Jeti - Relau Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:30 AM - 11:30 PM Monday 5:45 AM - 11:30 PM Jetty Pengkalan Weld, George Town Tuesday 5:45 AM - 11:30 PM Container Hotel Wednesday 5:45 AM - 11:30 PM Restoran Kapitan Thursday 5:45 AM - 11:30 PM 101 Lebuh King, George Town Friday 5:45 AM - 11:30 PM Kampung Kolam Saturday 5:30 AM - 11:30 PM 96 Lebuh Armenian, George Town Lebuh Carnarvon Komtar 301 bus Info 4-261 1121 182 Jalan Magazine, George Town Direction: Jeti - Relau Stops: 50 Terminal Komtar Trip Duration: 45 min Bus Way, George Town Line Summary: Jetty, Container Hotel, Restoran Kapitan, Kampung Kolam, Lebuh Carnarvon, Pasaraya Gama Komtar, Terminal Komtar, Pasaraya Gama, Penang Times Square, Pasar Jalan Kuantan, Jalan Patani., Penang Times Square Apartmen Taman Sri Pinang, Flat Ppr Jalan Sungai, Persimpangan Jalan S.P Chelliah, Pasar Lebuh Cecil, Pasar Jalan Kuantan Apartmen Desa Selatan, Peugeot Center, Mutiara Vista, Maybank Jelutong, Shell Jelutong, Taman Jalan Patani. Dato Syed Abbas, Masjid Jelutong, Pekan Jelutong, Pejabat Pos Jelutong, Bukit Dumbar, Recsam, Apartmen Taman Sri Pinang Astaka Gelugor, Bsn Gelugor, Restoran -

The State of Penang, Malaysia

Please cite this paper as: National Higher Education Research Institute (2010), “The State of Penang, Malaysia: Self-Evaluation Report”, OECD Reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development, IMHE, http://www.oecd.org/edu/imhe/regionaldevelopment OECD Reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development The State of Penang, Malaysia SELF-EVALUATION REPORT Morshidi SIRAT, Clarene TAN and Thanam SUBRAMANIAM (eds.) Directorate for Education Programme on Institutional Management in Higher Education (IMHE) This report was prepared by the National Higher Education Research Institute (IPPTN), Penang, Malaysia in collaboration with a number of institutions in the State of Penang as an input to the OECD Review of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. It was prepared in response to guidelines provided by the OECD to all participating regions. The guidelines encouraged constructive and critical evaluation of the policies, practices and strategies in HEIs’ regional engagement. The opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the National Higher Education Research Institute, the OECD or its Member countries. Penang, Malaysia Self-Evaluation Report Reviews of Higher Education Institutions in Regional and City Development Date: 16 June 2010 Editors Morshidi Sirat, Clarene Tan & Thanam Subramaniam PREPARED BY Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang Regional Coordinator Morshidi Sirat Ph.D., National Higher Education Research Institute, Universiti Sains Malaysia Working Group Members Ahmad Imran Kamis, Research Centre and -

A Systematic Literature Review Studies on George Town Festival (2010-2019)

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 10, No. 5, May, 2020, E-ISSN: 2222 -6990 © 2020 HRMARS A Systematic Literature Review Studies on George Town Festival (2010-2019) Dina Miza Suhaimi, Reevany Bustami To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i5/7318 DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i5/7318 Received: 12 March 2020, Revised: 16 April 2020, Accepted: 29 April 2020 Published Online: 20 May 2020 In-Text Citation: (Suhaimi & Bustami, 2020) To Cite this Article: Suhaimi, D. M., & Bustami, R. (2020). A Systematic Literature Review Studies on George Town Festival (2010-2019). International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 10(5), 869– 878. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 10, No. 5, 2020, Pg. 869 - 878 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 10, No. 5, May, 2020, E-ISSN: 2222 -6990 © 2020 HRMARS A Systematic Literature Review Studies on George Town Festival (2010-2019) Dina Miza Suhaimi1, 2 Reevany Bustami1 1Center for Policy Research and International Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800, Penang, Malaysia, 2Faculty of Technical and Vocational, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, 35900, Tanjong Malim, Perak Abstract George Town Festival (GTF) is a month-long festival that commemorates the inscription of George Town as a Cultural World Heritage Site (CWHS) by UNESCO in July 7, 2008.