The Overview of Traditional Life of Nagarathars – the Historical Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thirumayam Whether for Polling Location and Name of Building in All Voters Or Sl.No Station Polling Areas Which Polling Station Located Men Only Or No

AC181 - Thirumayam Whether for Polling Location and name of building in All Voters or Sl.No station Polling Areas which Polling Station located Men only or No. Women only 1 2 3 4 5 1 1 Panchayat Union Middle School 1.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-1 oliyamangalam , 2.Oliyamangalam (R.V), All Voters Tiled Building, West Portion Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-1 Eluvankurai , 3.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-2 ,Oliamangalam - 621308 Kayampatti , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS OVERSEAS ELECTORS 2 2 Panchayat Union Middle School 1.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-2 Kurunthadipatti , 2.Oliyamangalam (R.V), All Voters Tiled Building, East Portion Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-5 Servaikaranpatti , 3.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-5 ,Oliamangalam - 621308 Vengampatti , 4.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-5 Vettukadu , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS OVERSEAS ELECTORS 3 3 Panchayat Union Middle School 1.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-3 Surakkaipatti , 2.Oliyamangalam (R.V), All Voters West Portion Tiled Building Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-3 Sundampatti , 3.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-3 ,Oliamangalam, 621308 Madathupatti , 4.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-4 Vellalapatti , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS OVERSEAS ELECTORS 4 4 Panchayat Union Elementary 1.Vellayakoundampatti (R.V)Usilampatti (P) Ward-4 Vellayakoundampatti , 2.Avampatti (R.V), All Voters School, Terraced Building, Usilampatti (P) Ward-4 Avampatti , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS OVERSEAS ELECTORS ,Avampatti 622002 5 5 Panchayat Union Elementary -

Excavations at Keeladi, Sivaganga District, Tamil Nadu (2014 ‐ 2015 and 2015 ‐ 16)

Excavations at Keeladi, Sivaganga District, Tamil Nadu (2014 ‐ 2015 and 2015 ‐ 16) K. Amarnath Ramakrishna1, Nanda Kishor Swain2, M. Rajesh2 and N. Veeraraghavan2 1. Archaeological Survey of India, Guwahati Circle, Ambari, Guwahati – 781 001, Assam, India (Email: [email protected]) 2. Archaeological Survey of India, Excavation Branch – VI, Bangalore – 560 010, Karnataka, India (Email: [email protected], [email protected], snehamveera@ gmail.com) Received: 29 July 2018; Revised: 03 September 2018; Accepted: 18 October 2018 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 6 (2018): 30‐72 Abstract: The recent excavations at Keeladi have yielded interesting findings pertaining to the early historic period in southern Tamil Nadu. This article gives a comprehensive account of the prominent results obtained from two season excavations. The occurrence of elaborate brick structures, channels, paved brick floors associated with grooved roof tiles, terracotta ring wells in association with roulette ware and inscribed Tamil – Brahmi pot sherds is a rare phenomenon in the early historic phase of Tamil Nadu. The absolute dating (AMS) of the site to some extent coincides with the general perception of the so‐called Sangam period. Keywords: Keeladi, Early Historic, Excavation, Structures, Rouletted Ware, Tamil Brahmi, Ring Well Introduction The multi‐faceted antiquarian remains of Tamil Nadu occupy a place of its own in the archaeological map of India. It was indeed Tamil Nadu that put a firm base for the beginning of archaeological research in India especially prehistoric archaeology with the discovery of the first stone tool at Pallavaram near Madras by Sir Robert Bruce Foote in 1863. Ever since this discovery, Tamil Nadu witnessed many strides in the field of archaeological research carried out by various organizations including Archaeological Survey of India till date. -

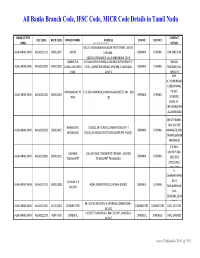

Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu

All Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu NAME OF THE CONTACT IFSC CODE MICR CODE BRANCH NAME ADDRESS CENTRE DISTRICT BANK www.Padasalai.Net DETAILS NO.19, PADMANABHA NAGAR FIRST STREET, ADYAR, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211103 600010007 ADYAR CHENNAI - CHENNAI CHENNAI 044 24917036 600020,[email protected] AMBATTUR VIJAYALAKSHMIPURAM, 4A MURUGAPPA READY ST. BALRAJ, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211909 600010012 VIJAYALAKSHMIPU EXTN., AMBATTUR VENKATAPURAM, TAMILNADU CHENNAI CHENNAI SHANKAR,044- RAM 600053 28546272 SHRI. N.CHANDRAMO ULEESWARAN, ANNANAGAR,CHE E-4, 3RD MAIN ROAD,ANNANAGAR (WEST),PIN - 600 PH NO : ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211042 600010004 CHENNAI CHENNAI NNAI 102 26263882, EMAIL ID : CHEANNA@CHE .ALLAHABADBA NK.CO.IN MR.ATHIRAMIL AKU K (CHIEF BANGALORE 1540/22,39 E-CROSS,22 MAIN ROAD,4TH T ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211819 560010005 CHENNAI CHENNAI MANAGER), MR. JAYANAGAR BLOCK,JAYANAGAR DIST-BANGLAORE,PIN- 560041 SWAINE(SENIOR MANAGER) C N RAVI, CHENNAI 144 GA ROAD,TONDIARPET CHENNAI - 600 081 MURTHY,044- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211881 600010011 CHENNAI CHENNAI TONDIARPET TONDIARPET TAMILNADU 28522093 /28513081 / 28411083 S. SWAMINATHAN CHENNAI V P ,DR. K. ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211291 600010008 40/41,MOUNT ROAD,CHENNAI-600002 CHENNAI CHENNAI COLONY TAMINARASAN, 044- 28585641,2854 9262 98, MECRICAR ROAD, R.S.PURAM, COIMBATORE - ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210384 641010002 COIIMBATORE COIMBATORE COIMBOTORE 0422 2472333 641002 H1/H2 57 MAIN ROAD, RM COLONY , DINDIGUL- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0212319 NON MICR DINDIGUL DINDIGUL DINDIGUL -

Nagarathar Matrimonial Services

Nagarathar Matrimonial Services https://www.indiamart.com/nagarathar-matrimonial-services/ n the earlier days in the Nagarathar community there were well informed elders in our native place who suggested suitable match for the boy or girl. All the marriage or religious functions are attended to by the eligible grooms and brides within ... About Us n the earlier days in the Nagarathar community there were well informed elders in our native place who suggested suitable match for the boy or girl. All the marriage or religious functions are attended to by the eligible grooms and brides within whom suitable alliances were matched. Now a days the, as the community is spread allover the globe, on their employment or occupation, the boy and girls are not able to find time/ interested to go to their native to attend the functions. Hence a place was required to make a link for those who seek alliance for their sons and daughters. A thoughtful Nagarathar Mr. M. Chidambaram Chettiar (Ex Indian Bank Officer) of Devakottai, felt the need of the hour and started the Nagarathar Thirumana Sevai Maiyam at Besant Nagar, Chennai in his own house. He was the forerunner in establishing such a service. After running the service for more than a decade he has decided to hand over the responsibility of continuing the service to a service minded person with a similar aspiration in the year 2001. He has rightly chosen Mr. SM. Lakshmanen of Devakottai who was also a retired Officer of Indian Bank, to succeed him in running the service from Jan. -

I Year Dkh11 : History of Tamilnadu Upto 1967 A.D

M.A. HISTORY - I YEAR DKH11 : HISTORY OF TAMILNADU UPTO 1967 A.D. SYLLABUS Unit - I Introduction : Influence of Geography and Topography on the History of Tamil Nadu - Sources of Tamil Nadu History - Races and Tribes - Pre-history of Tamil Nadu. SangamPeriod : Chronology of the Sangam - Early Pandyas – Administration, Economy, Trade and Commerce - Society - Religion - Art and Architecture. Unit - II The Kalabhras - The Early Pallavas, Origin - First Pandyan Empire - Later PallavasMahendravarma and Narasimhavarman, Pallava’s Administration, Society, Religion, Literature, Art and Architecture. The CholaEmpire : The Imperial Cholas and the Chalukya Cholas, Administration, Society, Education and Literature. Second PandyanEmpire : Political History, Administration, Social Life, Art and Architecture. Unit - III Madurai Sultanate - Tamil Nadu under Vijayanagar Ruler : Administration and Society, Economy, Trade and Commerce, Religion, Art and Architecture - Battle of Talikota 1565 - Kumarakampana’s expedition to Tamil Nadu. Nayakas of Madurai - ViswanathaNayak, MuthuVirappaNayak, TirumalaNayak, Mangammal, Meenakshi. Nayakas of Tanjore :SevappaNayak, RaghunathaNayak, VijayaRaghavaNayak. Nayak of Jingi : VaiyappaTubakiKrishnappa, Krishnappa I, Krishnappa II, Nayak Administration, Life of the people - Culture, Art and Architecture. The Setupatis of Ramanathapuram - Marathas of Tanjore - Ekoji, Serfoji, Tukoji, Serfoji II, Sivaji III - The Europeans in Tamil Nadu. Unit - IV Tamil Nadu under the Nawabs of Arcot - The Carnatic Wars, Administration under the Nawabs - The Mysoreans in Tamil Nadu - The Poligari System - The South Indian Rebellion - The Vellore Mutini- The Land Revenue Administration and Famine Policy - Education under the Company - Growth of Language and Literature in 19th and 20th centuries - Organization of Judiciary - Self Respect Movement. Unit - V Tamil Nadu in Freedom Struggle - Tamil Nadu under Rajaji and Kamaraj - Growth of Education - Anti Hindi & Agitation. -

Chapter Iii 67

CHAPTER I I I THE TEMPLES AND THE SOCIAL ORGANISATION OF THE CHETTIARS ' In the last chapter we sav that the Ilayathankudi Nagarathar emerged as a distinct endogamous Saiva Vaisya sub-caste, consisting of the patrilineal groups, each group attached to a temple located in the vicinity of Illayathankudi, somewhere around the eighth century A.D. In this chapter we shall see that contrary to the vehe ment propa^nda about the regressive effects of Hindu religion and social organization on the rational pursuit of profit, with the Chettiars, their very'*^religious affiliation and their form of social organization seem to have been shaped by their economic interests. It is significant that the social organization of this sub caste crystallized at a period v^hen the Tamil Country was rocked by a massive wave of Hindu revivalism that had arisen to counter the rising tide of the heterodox faiths of Buddhism’and Jainism. Buddhists and Jains had flou rished amicably along with Hindu Sects even during the Sangam age. But when Buddhism got catapulted into ascendency, under the ’Kalabhras’ , ”a rather mysterious and ubiquitous enemy of civilization”, who swept over ’ the Tamil Country and ruled it for over the two hundred years following the close of the Sangam age in thz4e hurylred A . D . , a hectic fury of re lig io u s hatred and r iv alry 67 6^ was unleashed.^ The active propagation of Buddhism by the ruling Kalabhras, who are denounced in the Velvikudi grants of the Pandyas (nineth century) as evil kings (kali- arasar) who uprooted many adhirajas, and confiscated the pro- 2 perties gifted to Gods (temples) and Brahmins, provoked the adherents of Siva and Vishnu to make organized attempts to stall the rising tide of heresy. -

G.I. Journal - 47 1 30/10/2012

G.I. JOURNAL - 47 1 30/10/2012 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS JOURNAL NO. 47 October 30, 2012/ KARTIKA 08, SAKA 1934 G.I. JOURNAL - 47 2 30/10/2012 INDEX S.No. Particulars Page No. 1. Official Notices 4 2. New G.I Application Details 5 3. Public Notice 6 4. GI Applications Pattamadai Pai (‘Pattamadai Mats’) – GI Application No. 195 Nachiarkoil Kuthvilakku (‘Nachiarkoil Lamp’) – GI Application No. 196 Chettinad Kottan – GI Application No. 200 Narayanpet Handloom Sarees – GI Application No. 214 5. General Information 6. Registration Process G.I. JOURNAL - 47 3 30/10/2012 OFFICIAL NOTICES Sub: Notice is given under Rule 41(1) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Rules, 2002. 1. As per the requirement of Rule 41(1) it is informed that the issue of Journal 47 of the Geographical Indications Journal dated 30th October 2012 / Kartika 08th, Saka 1934 has been made available to the public from 30th October 2012. G.I. JOURNAL - 47 4 30/10/2012 NEW G.I APPLICATION DETAILS 371 Shaphee Lanphee 25 Manufactured 372 Wangkhei Phee 25 Manufactured 373 Moirang Pheejin 25 Manufactured 374 Naga Tree Tomato 31 Agricultural 375 Arunachal Orange 31 Agricultural 376 Sikkim Large Cardamom 30 Agricultural 377 Mizo Chilli 30 Agricultural 378 Jhabua Kadaknath Black Chicken Meat 29 Manufactured 379 Devgad Alphonso Mango 31 Agricultural 380 RajKot Patola 24 Handicraft 381 Kangra Paintings 16 Handicraft 382 Joynagarer Moa 30 Food Stuff 383 Kullu Shawl (Logo) 24 Textile 23, 24, 384 Muga Silk of Assam (Logo) 25, 27 & Handicraft 31 385 Nagpur Orange 31 Agricultural 386 Orissa Pattachitra (Logo) 24 & 16 Handicraft G.I. -

CHETTINAD Travel Guide - Page 1

CHETTINAD Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/chettinad page 1 like Vairavan Kovil temple, Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. CHETTINAD Kundrakudi Murugan temple and others. Max: 28.1°C Min: 20.5°C Rain: 6.0mm Grand and majestic, every temple has its Mar Chettinad, a district of Sivaganga in own water lily filled water tank, ooranis, that Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. are sites for holy and temple rituals. Equally the state of Tamil Nadu and home Max: 31.9°C Min: 21.8°C Rain: 6.0mm awe inspiring are the 18th century mansions to the famous community of spread over the city. Palatial, furnished with Apr Nattukottai Chettiars, consists of a Burmese teaks with walls that were once Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. cluster of small villages that are polished with egg whites, these mansions Max: 25.4°C Min: 19.5°C Rain: 48.0mm known for their antiquity. The are a statement in elegant opulence. Yet May multitude of temples, ancient another fascinating aspect of Chettinad are Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. palaces and delicious cuisine make the saris produced here. Thick, heavy and Max: 23.1°C Min: 22.0°C Rain: 42.0mm it a thriving tourist slightly shorter in width than usual saris for Jun destination. women to be able to show off their anklets, Chettinad saris simply exude vibrancy and Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. Max: 29.1°C Min: 23.6°C Rain: 0.0mm sheer beauty in their deep, earthy colours. Jul Famous For : Cit Pleasant weather. -

A Brief History of Karaikudi

A Brief History of Karaikudi Karaikudi is a greater municipality in Sivaganga district in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu . It is the 20th largest urban agglomeration of Tamil Nadu based on 2011 census data. It is part of the area commonly referred to as " Chettinad " and has been declared a heritage town by the Government of Tamil Nadu ,[1] on account of the palatial houses built with limestone called karai veedu . Karaikudi comes under the Karaikudi assembly constituency, which elects a member to the Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly once every five years, and it is a part of the Sivaganga (Lok Sabha constituency) , which elects its member of parliament (MP) once in five years. The town is administered by the special grade Karaikudi municipality, which covers an area of 33.75 km 2 (13.03 sq mi). As of 2011, the town had a population of 106,714. Roadways are the major mode of transportation to Karaikudi and the nearest airports are Tiruchirapalli International Airport (TRZ) located (95 kilometres (59 mi)) and Madurai International Airport (IXM) is 97 km away from the town History The town derives its name from thorny plant Karai referred in ancient literature as Karaikudi , which in modern times became Karaikudi . The town was established in the 19th century, and the oldest known structure is the Koppudaiya Nayagi Amman Temple.[2] Mahatma Gandhi delivered two speeches in Karaikudi in 1927 and Bharathiyar visited Karaikudi in 1919 to participate in a function.Post independence, the town registered significant growth in the industrial sector. Karaikudi and surrounding areas are generally referred as "Chettinad".The town is home to Nagarathar , a business community and Chettiars , financiers and trade facilitators. -

DEVAKOTTAI MUNCIPALITY August, 2008

CITY CORPORATE CUM BUSINESS PLAN FINAL REPORT DEVAKOTTAI MUNCIPALITY August, 2008 Sponsored by Tamil Nadu Urban Infrastructure Financial Services Limited Government of Tamil Nadu Consultants FICHTNER Consulting Engineers (India) Private Ltd. Chennai – 600 028 CONTENTS I ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS II EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Page No 1 CONTEXT, CONCEPT AND CONTENTS OF CCCBP 1 1.1 Context of the Study 1 1.2 Objectives 1 1.3 Review meeting for Draft Final Reports 2 2 TOWN PROFILE, PHYSICAL PLANNING AND GROWTH MANAGEMENT 5 2.1 Regional Setting 5 2.2 Physical Features 5 2.3 Climate and Rainfall 5 2.4 History of the municipality 5 2.5 Demographic Features 6 2.5.1 Population and its growth 6 2.5.2 Population projection 6 2.5.3 Sex ratio and Literacy Rate 7 2.5.4 Density pattern 7 2.6 Occupational Pattern 7 2.7 Physical Planning and Growth Management 8 2.7.1 Land use and growth management 8 2.7.2 Growth Direction 9 2.7.3 Land Use Pattern 10 3 VISION AND STRATEGY 11 3.1 Stakeholders Workshop and Vision Statement 11 3.2 SWOT Analysis 12 3.3 Vision for Devakottai Town 12 3.4 Strategies for Economic Development 12 3.5 Urban Infrastructure 15 3.5.1 Vision 15 3.6 Performance and demand Assessment 16 3.7 Stratefies for Poverty Reduction and Slum Upgradation 18 3.8 Income Generation Activities 19 4 ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE 21 4.1 Elected Body 21 4.2 Executive Body 21 4.2.1 General Administration 22 4.2.2 Engineering Department 22 4.2.3 Accounts Department 22 4.2.4 Public Health Department 23 4.2.5 Town Planning Department 23 4.3 Staff Strength Position and Vacancy -

BUGEIA Camille Polytech Tours & Anna

BUGEIA Camille Polytech Tours & Anna University DAE5 May 2016 to September 2016 1 Figure 1 First courtyard of a Chettiar house in Kanadukathan (photo by M.SINOU) BUGEIA Camille Polytech Tours & Anna University DAE5 May 2016 to September 2016 2 BUGEIA Camille Polytech Tours & Anna University DAE5 May 2016 to September 2016 Content Part 2/3 Gallery ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Different attempts to protect the area........................................................................................................................................................ 13 A. Different type of projects ......................................................................................................................................................................... 13 Chettinad enhance via individual initiatives ................................................................................................................................................ 13 Chettinad enhance via institutions .............................................................................................................................................................. 13 B. An UNESCO application ............................................................................................................................................................................. 15 World Heritage -

ALAGAPPA UNIVERSITY ALAGAPPA UNIVERSITY (A State University Established in 1985) Karaikudi - 630 003, Tamil Nadu, India

ALAGAPPA UNIVERSITY ALAGAPPA UNIVERSITY (A State University Established in 1985) Karaikudi - 630 003, Tamil Nadu, India 35th South Zone Inter University Youth Festival - 2019 Date: 18th -22 nd December, 2019 In Collaboration with Organized by ALAGAPPA UNIVERSITY ALAGAPPA UNIVERSITY ASSOCIATION OF INDIAN Karaikudi - 630 003, UNIVERSITIES (AIU), Tamil Nadu. New Delhi. Virtual Presence: www.alagappauniversity.ac.in www.aiu.ac.in 35th South Zone Inter University Youth Festival - 2019 Alagu Fest celebrates the cultural diversity of South India with youthful joy and enthusiasm. Alagu Fest named after the host University and the name of its founder. Alagu means beautiful and this beautiful festival brings all the talents of youths of Southern India in the form of arts, literature, music, and the diverse forms of expressions. Alagu Fest would be the testimony for the diversity of culture, the spirit of oneness of this great nation India. 1 CONTENTS Sl. Contents Page No. No. 1 Letters to the Universities in South Zone of India 3 2 Gallery 5 3 Organizing Committee 6 4 Invitation 7 5 Details of Registration Fee 7 6 About Karaikudi & Its Surrounding 8 7 About Alagappa University, Karaikudi 11 8 Guidelines 14 9 Events at a Glance 15 10 Rules & Regulations 16 11 Annexure 26 12 Contact Details 31 2 3 Greetings from Alagappa University. Cultural festival is a celebration of the traditions of a particular people or place. Cultural celebrations foster respect and open-mindedness for other cultures. Celebrating our differences, as well as our common interests, helps unite and educate us. People all around need to understand and learn to appreciate other cultures, and this is one way to accomplish that.