ACCREDITATION S E L F - S T U D Y R E P O R T S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1996-1997 Game-By-Game Recaps

1996-1997 Game-by-Game Recaps March 1, at Urbana University The top-seeded Blue Knights rallied in the second half to force overtime and then outscored MVNC 16-7 in the extra period for a 112-103 victory in the semi-finals of the Mid-Ohio Conference Tournament. The Cougars led 51-43 at halftime, but Urbana forced 15 second-half turnovers as they mounted their comeback. Brad Hostasa led MVNC with a career-high 30 points on 11-of-13 shooting from the field. Ehren Hull added 21 points with three three- pointers as he set a new single-season mark for treys with 133. Scott Dapprich finished with 18 points and eight assists, and he tied the school's consecutive free throws made record with 27 straight makes. Todd Sands rounded out the double figure scorers with 10 points. February 27, TIFFIN UNIVERSITY In the first round of the Mid-Ohio Conference Tournament, the fourth-seeded Cougars knocked off fifth-seeded Tiffin 93-63 to set a new school record for wins in a season with 24. MVNC shot 64 percent from the field in the first half and nailed 12-of-18 three-point shots on their way to a 55-29 halftime lead. The Cougars finished the game with 20 three-pointers, two shy of the school record. Scott Dapprich led the way with a game-high 22 points on 6- of-7 three-point shooting. He also dished out a game-high seven assists. Ehren Hull added 16 points, while Chad Stevens finished with 15 points off the bench on 5-of-7 shooting from beyond the three-point arc. -

Selected Bibliography of American History Through Biography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 763 SO 007 145 AUTHOR Fustukjian, Samuel, Comp. TITLE Selected Bibliography of American History through Biography. PUB DATE Aug 71 NOTE 101p.; Represents holdings in the Penfold Library, State University of New York, College at Oswego EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 DESCRIPTORS *American Culture; *American Studies; Architects; Bibliographies; *Biographies; Business; Education; Lawyers; Literature; Medicine; Military Personnel; Politics; Presidents; Religion; Scientists; Social Work; *United States History ABSTRACT The books included in this bibliography were written by or about notable Americans from the 16th century to the present and were selected from the moldings of the Penfield Library, State University of New York, Oswego, on the basis of the individual's contribution in his field. The division irto subject groups is borrowed from the biographical section of the "Encyclopedia of American History" with the addition of "Presidents" and includes fields in science, social science, arts and humanities, and public life. A person versatile in more than one field is categorized under the field which reflects his greatest achievement. Scientists who were more effective in the diffusion of knowledge than in original and creative work, appear in the tables as "Educators." Each bibliographic entry includes author, title, publisher, place and data of publication, and Library of Congress classification. An index of names and list of selected reference tools containing biographies concludes the bibliography. (JH) U S DEPARTMENT Of NIA1.114, EDUCATIONaWELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OP EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED ExAC ICY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILYREPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTEOF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY PREFACE American History, through biograRhies is a bibliography of books written about 1, notable Americans, found in Penfield Library at S.U.N.Y. -

Xavier University 160Th Commencement Exercises, 1998 Xavier University, Cincinnati, OH

Xavier University Exhibit Xavier University Commencement Ceremonies University Archives and Special Collections Digital Collection 5-16-1998 Xavier University 160th Commencement Exercises, 1998 Xavier University, Cincinnati, OH Follow this and additional works at: https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/commencement 1 998 XAVIER UNIVERSITY 160TH COMMENCEMENT MAY 16,1998 8:45AM My VISION FOR XAVIER "My vision for Xavier is simple. What I want most of all is that a Xavier education be ofsuch qualitythat each and every graduate will say: 'I received an absolutely superb education at Xavier. I could not have received a finer education any where in the world.' I want every Xavier graduate to say: 'I know that I am intellectually, morally and spiritually pre pared to take my place in a rapidly changing global society and to have a positive impact on that society - to live a life beyond myself for other people.' " James E. Hoff S.] President Xavier Uniz}ersity My VISION FOR XAVIER "My vision for Xavier is simple. What 1 want most of all is that a Xavier education be ofsuch quality that each and every graduate will say: 'I received an absolutely superb education at Xavier. 1 could not have received a finer education any where in the world.' 1 want every Xavier graduate to say: 'I know that I am intellectually, morally and spiritually pre pared to take my place in a rapidly changing global society and to have a positive impact on that society - to live a life beyond myself for other people.' " James E. Hoff, S.]. President Xtwier University XAVIER UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES Michael]. -

A New President for Rio: Meet Ryan Smith

2019 Quarterly – Issue 3 A New President for Rio: Meet Ryan Smith With his vast financial and business Colleges and universities across the country background, leadership roles, and a list of are facing declining enrollment. The changes contacts and connections he brings with you are seeing, especially with the recent him from the State, Smith’s message is changes to program offerings, help Rio to all about “changing tomorrow’s”. He feels be more streamlined and nimbler in the strongly our region needs a two and four- challenging times ahead. Recruitment and year degree granting institution, and will retention remain high priorities and our strive to keep Rio moving forward so its efforts have led to an increase in private university students for this fall semester. President Ryan Smith impact is long-standing. When asked what his message to alumni Your support of Rio remains as critical as ever. The President’s seat at the University of Rio would be, Mr. Smith replied: We welcome President Smith and will look Grande and Rio Grande Community College for many ways for you to engage with him as was filled earlier this month by a lifelong “As a lifelong resident of Gallia County, I fully Rio Grande moves forward to a prosperous resident of Gallia County, Mr. Ryan Smith. understand and appreciate the vast impact future. My work will continue to keep you Rio Grande has made on so many lives in our informed and engaged, and I always hope to Smith, whose name you might recognize region, and well beyond. As alumni, you tell see your #RioPride wherever you may be. -

University of Cincinnati 2016 Campus Climate Survey Results Summary

University of Cincinnati 1 University of Cincinnati 2016 Campus Climate Survey Results Summary The State of Ohio’s Changing Campus Culture Initiative seeks to strengthen its ability to better respond to, and ultimately prevent, sexual assault on the state’s college campuses. In the spring 2016, all Ohio campuses were encouraged to participate in recommendation #1 in the Changing Campus Culture report: use data to guide action. In addition to completing a comprehensive campus climate survey, Ohio campuses were also asked to disseminate 15 common benchmark questions. The purpose of the benchmark questions was to provide the Ohio Department of Higher Education with a common set of data to measure statewide progress in addressing prevention and response to sexual violence, and to track trends over time. While campuses were free to determine which climate survey best fit their campus community, the benchmark questions were the same to allow for comparison between one campus and others of similar type. Methodology and Sample Data collection began in the 2016 spring semester and ended by June 2016. Institutions collected data in various ways, including through paper surveys and electronically. All responses were anonymous. Each participating school was asked to gather data on the benchmark questions along with provided demographic questions. Response scales for the benchmark questions and demographic questions varied slightly for some institutions, and any questions with substantively different response scales were excluded from the aggregate analyses. 14 public university main campuses, 23 community/state/technical colleges, and 35 private institutions participated in the survey. The overall sample included 23,240 students across the sampled 71 higher education institutions. -

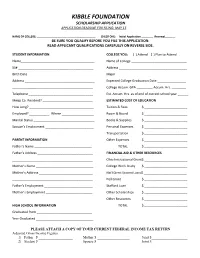

Kibble Foundation Scholarship Application Application Deadline for Filing: May 15

KIBBLE FOUNDATION SCHOLARSHIP APPLICATION APPLICATION DEADLINE FOR FILING: MAY 15 NAME OF COLLEGE: ________________________________________ CHECK ONE: Initial Application ________ Renewal_______ BE SURE YOU QUALIFY BEFORE YOU FILE THIS APPLICATION. READ APPLICANT QUALIFICATIONS CAREFULLY ON REVERSE SIDE. STUDENT INFORMATION COLLEGE YOU: ( ) Attend ( ) Plan to Attend Name_________________________________________ Name of College _______________________________ SS# __________________________________________ Address ______________________________________ Birth Date _____________________________________ Major _______________________________________ Address _______________________________________ Expected College Graduation Date ________________ _____________________________________________ College Accum. GPA _________ Accum. Hrs. ________ Telephone ____________________________________ Est. Accum. Hrs. as of end of current school year ______ Meigs Co. Resident? ____________________________ ESTIMATED COST OF EDUCATION How Long? ____________________________________ Tuition & Fees $ ________________________ Employed? __________ _ Where __________________ Room & Board $ ________________________ Marital Status __________________________________ Books & Supplies $ ________________________ Spouse’s Employment ___________________________ Personal Expenses $ ________________________ Transportation $ ________________________ PARENT INFORMATION Other Expenses $ ________________________ Father’s Name ________________________________ TOTAL $ ________________________ -

Colleges & Universities

Bishop Watterson High School Students Have Been Accepted at These Colleges and Universities Art Institute of Chicago Fordham University Adrian College University of Cincinnati Franciscan University of Steubenville University of Akron Cincinnati Art Institute Franklin and Marshall College University of Alabama The Citadel Franklin University Albion College Claremont McKenna College Furman University Albertus Magnus College Clemson University Gannon University Allegheny College Cleveland Inst. Of Art George Mason University Alma College Cleveland State University George Washington University American Academy of Dramatic Arts Coastal Carolina University Georgetown University American University College of Charleston Georgia Southern University Amherst College University of Colorado at Boulder Georgia Institute of Technology Anderson University (IN) Colorado College University of Georgia Antioch College Colorado State University Gettysburg College Arizona State University Colorado School of Mines Goshen College University of Arizona Columbia College (Chicago) Grinnell College (IA) University of Arkansas Columbia University Hampshire College (MA) Art Academy of Cincinnati Columbus College of Art & Design Hamilton College The Art Institute of California-Hollywood Columbus State Community College Hampton University Ashland University Converse College (SC) Hanover College (IN) Assumption College Cornell University Hamilton College Augustana College Creighton University Harvard University Aurora University University of the Cumberlands Haverford -

Cedarville College Vs. University of Rio Grande Cedarville College

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Volleyball News Releases Volleyball 10-22-1998 Cedarville College vs. University of Rio Grande Cedarville College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ volleyball_news_releases Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cedarville College, "Cedarville College vs. University of Rio Grande" (1998). Volleyball News Releases. 41. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/volleyball_news_releases/41 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volleyball News Releases by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1998 CEDARVILLE COLLEGE VOLLEYBALL Thursday, Oct. 22, 1998 Athletic Center 7:00 pm Cedarville College vs. University of Rio Grande TONIGHT'S MATCH • 1998 SCHEDULE/RESULTS • The Cedarville College women's volleyball team hosts the University Sept. 4 CENTRAL STATE UNIVERSITY W 15·0, 15·2, 15-0 of Rio Grande in an American Mideast Conference match tonight in the Sept. 4 URBANA UNIVERSITY W 15-4, 15-2, 15·6 Athletic Center. Cedarville captured their 20th win of the season on Sept. 5 UNIVERSITY OF INDIANAPOLIS W 10·15, 8·15, 15-9, 15·7, 17-15 Sept. 5 INDIANA WESLEYAN Tuesday with a 15-0, 15-8, 15- IO win over Urbana. The Lady Jackets are W 15·10, 15-13, 15·7 Sept. 5 GRACE COLLEGE W 15-8, 12-15, 15-11, 15-10 I 1-2 in the AMC and still battling for the top spot in the conference stand Sept. -

Arts and Sciences, Subtheme: Education XX William Holmes Mcguffey Boyhood Home Site William Holmes Mcguffey Boyhood Home Site Yo

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK Arts and Sciences, subtheme: Education XX Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Ohio COUN T Y: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Mahoning INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM _______FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries complete applicable sections) C OMMON: William Holmes McGuffey Boyhood Home Site AND/OR HISTORIC: William Holmes McGuffey Boyhood Home Site STREET AND NUMBER: 4505 McGuffey Road CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: geungotown CaJrbw\\e~~TowfNsW 19th STATE Ohio 39 Mahoning 099 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District Q Building Public Public Acquisition: ccupied Yes: XX Restricted Site Q Structure Private XX In Process [~~j Unoccupied Q Unrestricted Object Both [~~j Being Considered !Q(Preservation work in progress a NO PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) KX Agricultural I I Government D Park 1 I Transportation [~~j Comments 1~1 Commercial [~~j Industrial [~~j Private Residence n Other (Specify) I I Educational D Military [~1 Religious 1 I Entertainment [~~j Museum [~~j Scientific OWNER'S NAME: Mr. Julius Laurie STREET AND NUMBER: 4505 McGuffey Road CITY OR TOWN: CODF Youngstown (Coitsville Township) Ohio 099 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC: Registry of Deeds __ STREET AND NUMBER: 120 Market Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE Youngstown Ohio 39 TITLE OF SURVEY: None DATE OF SURVEY: Federal Q State County Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: (Check One) Excellent D Good [v] Fair Q Deteriorated Q Ruins Q Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) CC/iec/c One; Altered Q Unaltered Moved XX Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARAMCE The William Holmes McGuffey Boyhood Home Site is located on McGuffey Road near its intersection with State Highway 616, in Coitsville Township, Mahoning County. -

William Mcguffey and the Mcguffey Eclectic Readers by Karla Perry

May 18, 2012 The Restoration of America: William McGuffey and the McGuffey Eclectic Readers By Karla Perry American children of the mid-nineteenth century were essentially educated by the works of one man, William Holmes McGuffey. The McGuffey Eclectic Readers sold 120 million copies between 1836 and 1920. These sales are comparable only to the Bible and Webster’s Dictionary.1 William Holmes McGuffey [1800-1873] began his educational profession at the age of fourteen after receiving a teaching certificate from his educator, Reverend William Wick. As instructed, he put an advertisement in the local paper that he would begin a four-month session of classes, six days a week, and eleven hours a day on the first day of September 1814. Forty-eight students assembled from the West Union, Ohio community, now Calcutta, Ohio. McGuffey drew his lessons primarily from the Bible.2 A traveling Presbyterian Pastor took notice of McGuffey’s teaching skills and offered to take him to reside in his home while he attended Old Stone Academy. McGuffey did so for the next four years. He then continued his education at Washington College for the next six years, where he worked the farm to pay for his education, taught, and studied. When he couldn’t afford to buy his books, he copied them longhand. Before completing his degree, he was offered to become a professor at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. He accepted this position which he held for ten years before moving to Charlottesville, Virginia, where he would be a professor at the University of Virginia for twenty-eight years. -

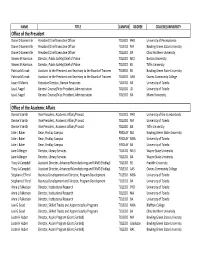

20210415 Degree Admin.Xlsx

NAME TITLE CAMPUS DEGREE COLLEGE/UNIVERSITY Office of the President Dione D Somerville President/Chief Executive Officer TOLEDO PHD University of Pennsylvania Dione D Somerville President/Chief Executive Officer TOLEDO MA Bowling Green State University Dione D Somerville President/Chief Executive Officer TOLEDO BA Ohio Northern University Steven M Harrison Director, Public Safety/Chief of Police TOLEDO MCJ Boston University Steven M Harrison Director, Public Safety/Chief of Police TOLEDO BS Tiffin University Patricia M Jezak Assistant to the President and Secretary to the Board of Trustees TOLEDO BS Bowling Green State University Patricia M Jezak Assistant to the President and Secretary to the Board of Trustees TOLEDO AAB Owens Community College Jason V Morris Executive Director, Human Resources TOLEDO BA University of Toledo Lisa L Nagel General Counsel/Vice President, Administration TOLEDO JD University of Toledo Lisa L Nagel General Counsel/Vice President, Administration TOLEDO BA Miami University Office of the Academic Affairs Denise S Smith Vice President, Academic Affairs/Provost TOLEDO PHD University of the Cumberlands Denise S Smith Vice President, Academic Affairs/Provost TOLEDO MA University of Toledo Denise S Smith Vice President, Academic Affairs/Provost TOLEDO BA Tiffin University Julie L Baker Dean, Findlay Campus FINDLAY MA Bowling Green State University Julie L Baker Dean, Findlay Campus FINDLAY MBA University of Toledo Julie L Baker Dean, Findlay Campus FINDLAY BA University of Toledo Jane A Berger Director, Library Services -

Our Christian Educational Heritage: Mcguffey and His Readers by Robert A

Our Christian Educational Heritage: McGuffey and His Readers By Robert A. Peterson From no other source has the author drawn more copiously in his selections than from the Sacred Scriptures. For this, he certainly apprehends no censure. In a Christian country, that man is to be pitied who, at this day, can honestly object to imbuing the minds of youth with the language and the spirit of the Word of God. -William Holmes McGuffey In the year 1928 Henry ford personally issued a reprint of the books through which he had been taught to read. Reflecting on their significance in his own education, he wrote: Most youngsters of my day were brought up on the McGuffey Readers. Most of those youngsters who still survive have a profound respect for the compiler of the Readers. The moral principles Dr. William Holmes McGuffey stressed, the solid character building qualities he emphasized, are stressed and emphasized . today even though the McGuffey’s Readers themselves are not “required reading.” Nearly sixty years have passed since Ford wrote these words, yet interest in McGuffey’s Readers show no signs abating. Between 1836 and 1920, over 120 million copies of McGuffey’s Readers were sold. Since 1961, they have continued to sell at a rate of some 30,000 copies each year, and a new edition of the original McGuffey’s Readers recently published by Mott Media promises to generate even more interest in the Readers. With the exception of the Bible, McGuffey’s Readers probably did the most to shape American values and morals in the nineteenth century.