The Alleged Incapacities of Mr Sheridan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School Meals (Scotland) Bill (SP Bill 42) As Introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 14 November 2001

This document relates to the School Meals (Scotland) Bill (SP Bill 42) as introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 14 November 2001 SCHOOL MEALS (SCOTLAND) BILL —————————— POLICY MEMORANDUM INTRODUCTION 1. This document relates to the School Meals (Scotland) Bill introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 14 November 2001. It has been prepared by Tommy Sheridan, the member in charge of the Bill, in accordance with Rule 9.3.3A of the Parliament’s Standing Orders. The contents are entirely the responsibility of the member and have not been endorsed by the Parliament. Explanatory Notes and other accompanying documents are published separately as SP Bill 42–EN. POLICY OBJECTIVES OF THE BILL 2. The main purpose of the Bill is to give children the right to a free and nutritious school meal and drink at schools under the management of local authorities in Scotland. 3. The school meals service in Scotland has been in a state of decline since 1980 when the Education (Scotland) Act 1980 deregulated school meals and removed nutritional standards. This led to school meals having a higher saturated fat content, smaller portions, higher prices and a steep decline in take-up of school meals.1 4. Section 53 of the Education (Scotland) Act 1980 sets out the current legal position with respect to school meals in Scotland. It places a duty on education authorities to provide free school meals in the middle of the day to pupils whose parents are in receipt of income support, income-based jobseeker’s allowance, or support under Part VI of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999. -

SLR I15 March April 03.Indd

scottishleftreview comment Issue 15 March/April 2003 A journal of the left in Scotland brought about since the formation of the t is one of those questions that the partial-democrats Scottish Parliament in July 1999 Imock, but it has never been more crucial; what is your vote for? Too much of our political culture in Britain Contents (although this is changing in Scotland) still sees a vote Comment ...............................................................2 as a weapon of last resort. Democracy, for the partial- democrat, is about giving legitimacy to what was going Vote for us ..............................................................4 to happen anyway. If what was going to happen anyway becomes just too much for the public to stomach (or if Bill Butler, Linda Fabiani, Donald Gorrie, Tommy Sheridan, they just tire of the incumbents or, on a rare occasion, Robin Harper are actually enthusiastic about an alternative choice) then End of the affair .....................................................8 they can invoke their right of veto and bring in the next lot. Tommy Sheppard, Dorothy Grace Elder And then it is back to business as before. Three million uses for a second vote ..................11 Blair is the partial-democrat par excellence. There are David Miller two ways in which this is easily recognisable. The first, More parties, more choice?.................................14 and by far the most obvious, is the manner in which he Isobel Lindsay views international democracy. In Blair’s world view, the If voting changed anything...................................16 purpose of the United Nations is not to make a reasoned, debated, democratic decision but to give legitimacy to the Robin McAlpine actions of the powerful. -

Candidate Votes Per Stage Report Stage 1

South Lanarkshire Council Candidate Votes Per Stage Report This report describes votes attained by candidates at each stage. Contest Name Ward 15 - Blantyre Total number of Ballot Papers Received 5,542 Total Number of Valid Votes 5,362 Positions to be Filled 3 Quota 1,341 Stage 1 Candidate Name Affiliation Transfer Value Votes Status Maureen CHALMERS Scottish National Party (SNP) 0.00000 1,354.00000 Elected Scottish Conservative and 0.00000 593.00000 Alan Henderson FRASER Unionist Tommy Sheridan - Solidarity - 0.00000 76.00000 Ashley HUBBARD Hope Over Fear Michael MCGLYNN Scottish National Party (SNP) 0.00000 797.00000 Scottish Socialist Party - Save 0.00000 48.00000 Gerry MCMAHON our services Mo RAZZAQ Scottish Labour Party 0.00000 1,663.00000 Elected Stephen REID Scottish Liberal Democrats 0.00000 100.00000 Bert THOMSON Scottish Labour Party 0.00000 731.00000 Non-transferable votes 0.00000 0.00000 Total 5,362.00000 Report Name: CandidateVotesPerStage_Report_Ward_15_-_Blantyre_05052017_153000.pdf Created: 05-5-2017 15:30:00 South Lanarkshire Council Candidate Votes Per Stage Report This report describes votes attained by candidates at each stage. Stage 2 Surplus of Mo RAZZAQ Candidate Name Affiliation Transfer Value Votes Status Maureen CHALMERS Scottish National Party (SNP) 0.00000 1,354.00000 Scottish Conservative and 7.93842 600.93842 Alan Henderson FRASER Unionist Tommy Sheridan - Solidarity - 4.25964 80.25964 Ashley HUBBARD Hope Over Fear Michael MCGLYNN Scottish National Party (SNP) 18.58752 815.58752 Scottish Socialist Party - Save 3.48516 51.48516 Gerry MCMAHON our services Mo RAZZAQ Scottish Labour Party -322.00000 1,341.00000 Stephen REID Scottish Liberal Democrats 8.71290 108.71290 Bert THOMSON Scottish Labour Party 248.99532 979.99532 Non-transferable votes 30.02104 30.02104 Total 5,362.00000 Report Name: CandidateVotesPerStage_Report_Ward_15_-_Blantyre_05052017_153000.pdf Created: 05-5-2017 15:30:00 South Lanarkshire Council Candidate Votes Per Stage Report This report describes votes attained by candidates at each stage. -

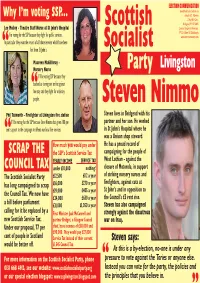

Livi Leaflet 2 Front&Back

ELECTION COMMUNICATION published by B. Lebrun on Why I’m voting SSP... behalf of S. Nimmo 21 Auldhill Cres, Bridgend, EH49 6NX Lee Molloy - Theatre Staff Nurse at St John’s Hospital Scottish printed by Events Armoury, 17-23 Calton Rd, Edinburgh I’m voting for the SSP because they fight for public services. www.eventsarmoury.com In particular they want the return of all those services which have been “ lost from St John’s. Socialist Maureen McGillivray - Nursery Nurse Party Livingston I’ll be voting SSP because they backed us during our strike against “low pay and they fight for ordinary people. Steven Nimmo Phil Tuxworth - Firefighter at Livingston fire station Steven lives in Bridgend with his I’ll be voting for the SSP because Steve Nimmo has given 100 per partner and her son. He worked cent support to the campaign to defend our local fire services. in St John’s Hospital where he “ was a Unison shop steward. How much you would pay under He has a proud record of SCRAP THE the SSP’s Scottish Service Tax: campaigning for the people of YEARLY INCOME SERVICE TAX West Lothian - against the COUNCIL TAX under £10,000 nothing! closure of Motorola, in support The Scottish Socialist Party £12,500 £112 a year of striking nursery nurses and has long campaigned to scrap £16,000 £270 a year firefighters, against cuts at St John’s and in opposition to the Council Tax. We now have £19,000 £405 a year £24,000 £630 a year the Council’s £5 rent rise. -

Scottish Parliamentary Election Results – 3 May 2007

Scottish Parliamentary Election Results – 3 May 2007 Banff and Buchan Constituency Name Party Votes Kay BARNETT Scottish Labour Party Candidate 3,136 George Slessor Scottish Conservative and Unionist 5,501 Burnett STUART Alison McINNES Scottish Liberal Democrats 2,617 Stewart STEVENSON Scottish National Party (SNP) 16,031 Majority: 10,530 Turnout: 51.0% Rejected Ballots: 1,443 Regional List Party Votes Alex Salmond for First Minister 16,232 British National Party Local People First 388 Christian Peoples Alliance Leader Teresa Smith 157 Scottish Christian Party "Proclaming Christ's Lordship" 406 Scottish Conservative and Unionist 4,358 Scottish Enterprise Party 21 Scottish Green Party 524 Scottish Labour Party 3,122 Scottish Liberal Democrats 2,018 Scottish Senior Citizens Unity Party 397 Scottish Socialist Party Independent Socialist Scotland 93 Scottish Voice NHS First 70 Socialist Labour Party 127 Solidarity Tommy Sheridan 146 UKIPScotland 168 Rejected Ballots: 501 Gordon Constituency Name Party Votes Neil John CARDWELL Scottish Labour Party Candidate 2,276 Robert Paton INGRAM Scottish Enterprise Party 117 Donald Henry Albert MARR Independent 199 Steven David MATHERS Independent 185 Nanette Lilian Margaret MILNE Scottish Conservative and Unionist 5348 Nora RADCLIFFE Scottish Liberal Democrats 12588 Alexander Elliot Anderson Scottish National Party (SNP) 14,650 SALMOND Majority: 2,062 Turnout: 55.3% Rejected Ballots: 849 Regional List Party Votes Alex Salmond for First Minister 14,936 British National Party Local People First 340 -

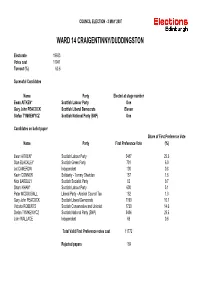

Craigentinny/Duddingston Ward Results 2007

COUNCIL ELECTION - 3 MAY 2007 WARD 14 CRAIGENTINNY/DUDDINGSTON Electorate 19693 Votes cast 11941 Turnout (%) 60.6 Sucessful Candidates Name Party Elected at stage number Ewan AITKEN* Scottish Labour Party One Gary John PEACOCK Scottish Liberal Democrats Eleven Stefan TYMKEWYCZ Scottish National Party (SNP) One Candidates on ballot paper Share of First Preference Vote Name Party First Preference Vote (%) Ewan AITKEN* Scottish Labour Party 3487 29.6 Stan BLACKLEY Scottish Green Party 701 6.0 Jet CAMERON Independent 100 0.8 Kevin CONNOR Solidarity - Tommy Sheridan 187 1.6 Nick EARDLEY Scottish Socialist Party 82 0.7 Shami KHAN* Scottish Labour Party 600 5.1 Peter MCDOUGALL Liberal Party - Abolish Council Tax 152 1.3 Gary John PEACOCK Scottish Liberal Democrats 1190 10.1 Victoria ROBERTS Scottish Conservative and Unionist 1720 14.6 Stefan TYMKEWYCZ Scottish National Party (SNP) 3484 29.6 John WALLACE Independent 69 0.6 Total Valid First Preference votes cast 11772 Rejected papers 169 COUNCIL ELECTION - 3 MAY 2007 % Share of First Preference Vote (%) Craigentinny/Duddingston Ward 40.0 35.0 30.0 25.0 20.0 15.0 10.0 5.0 0.0 Scottish Labour Scottish National Scottish Scottish Liberal Scottish Green Solidarity - Liberal Party - Jet Cameron Scottish Socialist John Wallace Party Party (SNP) Conservative and Democrats Party Tommy Sheridan Abolish Council (Independent) Party (Independent) Unionist Tax s Full Result Sheet (printable version) » Craigentinny/Duddingston Election For FINAL REPORT Date 04/05/2007 Number to be elected 3 Valid Votes 11772 -

Black and White, Migrant and Local, Religious Or Not: Workers Unite! 2 NEWS

For a Solidarity workers’ government For social ownership of the banks and industry No 342 5 November 2014 30p/80p www.workersliberty.org Down with UKIP! Up with solidarity! Black and white, migrant and local, religious or not: workers unite! 2 NEWS What is the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty? NHS staff to strike again Today one class, the working class, lives by selling its labour power to another, the capitalist class, which owns the means of production. By Todd Hamer defending our already much Society is shaped by the capitalists’ relentless drive to increase their degraded terms and condi - wealth. Capitalism causes poverty, unemployment, the Health unions have an - tions, then we will have blighting of lives by overwork, imperialism, the nounced a further four helped speed on the end of destruction of the environment and much else. hour strike on 24 Novem - the NHS as a free state-of- Against the accumulated wealth and power of the ber in their ongoing pay the-art health service. capitalists, the working class has one weapon: dispute. solidarity. But the current strategy of The Alliance for Workers’ Liberty aims to build Since 2010 the NHS has the unions is risible. So far solidarity through struggle so that the working class can overthrow been starved of £20 billion. the campaign has involved a capitalism. We want socialist revolution: collective ownership of By 2020 the gap between four hour strike, four days industry and services, workers’ control and a democracy much fuller funding and necessary ex - of not doing unpaid over - than the present system, with elected representatives recallable at any penditure will be around time (so-called “action short time and an end to bureaucrats’ and managers’ privileges. -

Interview Summary: Start 0:30 – Came to Stirling in 1969

SURSA University of Stirling Stirling FK9 4LA SURSA [email protected] www.sursa.org.uk Interviewee: John McCracken. Dr UoS Dates: 1968 - 2003 Role(s): Lecturer, latterly Senior Lecturer in the Dept of History. Founding Director of the Centre for Commonwealth Studies. Currently Hon Senior Research Fellow Interview summary: Start 0:30 – Came to Stirling in 1969. For the previous four years, he was at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. It was a lively and intellectually exciting place, but it was time for an expatriate to move on. He wanted to return to Scotland, and the Stirling job came up. They wanted an African historian, and JM was attracted by the idea of working with George Rudé, the first professor of history because his own interest was in history from below. 2:30 – He came from Dar es Salaam for an interview. It was very cold, his luggage was mislaid. On the steps of Pathfoot, he first caught sight of miniskirts. The campus was looking wonderful, paintings everywhere … all very desirable. 3:30 – He was interviewed by David Waddell, Eric Richards. (George Rudé had already left.) They asked him to wait for an hour, and then offered him the job. Anand Chitnis drove him around to look at places to live. He was impressed that a new university was making an appointment in African history. 5:00 – George Rudé had structured the courses in the department to follow his own Marxist model. David Waddell, a Latin American historian, changed the emphasis to cover new areas: hence the desire to appoint an African historian. -

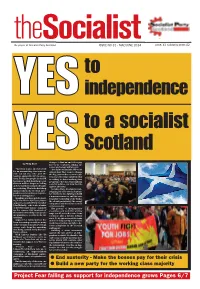

Project Fear Failing As Support for Independence Grows Pages 6/7 2 Editorial the Socialist - May/June 2014

the Socialist The paper of Socialist Party Scotland ISSUE NO 31 - MAY/JUNE 2014 price: £1 solidarity price: £2 to YES independence to a socialist Scotland doing so to find an end to low pay, by Philip Stott zero-hour contracts, falling in - YEcomesS and savage welfare cuts. “Austerity is just another word Alex Salmond and the SNP won’t for an unremitting class war car - deliver that. They want to change ried out by the elite and the the flag, but not the economic sys - bankers against the 99% in our so - tem of profiteering capitalism that ciety. Today, five people in the UK is seeking to drive working class have more wealth than the poorest people into the dust. Only fighting thirteen million. Wages are falling socialist policies can turn the tide and the numbers using food banks against austerity. are rocketing. That’s the backdrop Socialist Party Scotland is cam - against which the Scottish inde - paigning for a Yes vote in Septem - pendence referendum on Septem - ber. But we’re also fighting to build ber 18 is taking place.” a mass movement to end the cuts, Speaking at a huge public meet - for public ownership of the banks, ing in Dundee in April (see picture the oil and gas industry, the energy opposite), Socialist Party member companies and the major sectors John McInally – who is also a leader of the economy. of the PCS trade union - summed The powers of independence up the reasons why hundreds of should be used to deliver a living thousands of working class people wage for all, an end to zero hour are planning to vote Yes in the ref - contracts and a decent welfare erendum. -

South and North Kincardine Declaration

Scottish Parliament election Declaration of constituency result Aberdeen South & North Constituency Kincardine Date of election Thursday 5 May 2016 I, Angela Scott, Constituency Returning Officer, hereby declare the results of the verification process for the Aberdeen South & North Kincardine Scottish Parliament Constituency. Electorate 59,710 Total votes cast 32,471 Turnout 54.38% I, Angela Scott, Constituency Returning Officer for the Scottish Parliamentary Election in the Aberdeen South & North Kincardine Constituency hereby give Notice that the total number of votes polled for each candidate at the election was as follows:- Candidate Description Number Share of votes EVISON, Alison Scottish Labour Party 5,603 17.3% THOMSON, Ross Scottish Conservative and Unionist 10,849 33.5% Party WADDELL, John Scottish Liberal Democrats 2,284 7.1% WATT, Maureen Scottish National Party (SNP) 13,604 42.1% Total Valid Votes 32,340 The total number of rejected votes was 131. The reason for rejection was as follows: Reason for rejection Number Share of votes Lack of official mark or unique identifying mark 0 0% Voting for more than one candidate 28 21.4% Writing or mark by which the voter could be identified 1 0.8% Unmarked or void for uncertainty 102 77.8% Total Rejected Votes 131 The following candidate is duly elected to serve as a Member of the Scottish Parliament for the Aberdeen South & North Kincardine constituency: Maureen Watt Scottish National Party (SNP) Angela Scott Constituency Returning Officer 6th May 2016 Scottish Parliament election Declaration of regional votes cast in a constituency Aberdeen South & North Constituency Kincardine Date of election Thursday 5 May 2016 I, Angela Scott, Constituency Returning Officer, hereby declare the results of the verification process for the Scottish Parliament Regional List within the Aberdeen South & North Kincardine Constituency. -

The Pro-Independence Radical Left in Scotland Since 2012 Nathalie DUCLOS Université De Toulouse 2-Jean Jaurès

The Pro-independence Radical Left in Scotland since 2012 Nathalie DUCLOS Université de Toulouse 2-Jean Jaurès The Pro-independence Radical Left in Scotland since 2012 Nathalie DUCLOS Université de Toulouse 2-Jean Jaurès CAS EA 801 [email protected] Résumé Cet article a pour objectif de dessiner les contours de la gauche radicale et indépendantiste dans l’Écosse d’aujourd’hui. La longue campagne qui a précédé le référendum sur l’indépendance écossaise de 2014 (celle-ci ayant commencé dès 2012, soit plus de deux ans avant le référendum lui-même) a donné naissance à un nouveau paysage politique, surtout à gauche. Celui-ci se caractérise par deux tendances : la multiplication de nouvelles organisations (par exemple la Radical Independence Campaign, Common Weal et le Scottish Left Project), souvent (mais pas toujours) favorables à l’indépendance écossaise, et le renforcement des partis indépendantistes de gauche ou de centre-gauche déjà existants, qui ont tous gagné énormément de nouveaux adhérents. Cet article se concentre sur les organisations indépendantistes de la gauche radicale en Écosse : celles créées depuis 2012, ainsi que celles qui leur ont donné naissance. Après avoir présenté chacune de ces organisations et les liens qui existent entre elles, il se penche sur leurs stratégies à court terme (présenter des candidats et remporter des sièges aux élections parlementaires écossaises de 2016) et à moyen ou long terme (faire campagne pour l’organisation d’un nouveau référendum sur l’indépendance écossaise et proposer une vision de l’indépendance différente de celle mise en avant par le Scottish National Party). Abstract This article aims at mapping the pro-independence radical left in today’s Scotland. -

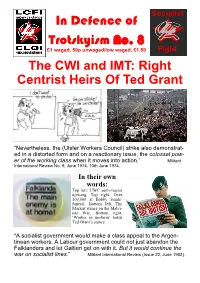

In Defence of Trotskyism No. 8

In Defence of Trotskyism No. 8 £1 waged, 50p unwaged/low waged, €1.50 The CWI and IMT: Right Centrist Heirs Of Ted Grant “Nevertheless, the (Ulster Workers Council) strike also demonstrat- ed in a distorted form and on a reactionary issue, the colossal pow- er of the working class when it moves into action.” Militant International Review No. 9, June 1974. 10th June 1974. In their own words: Top left: UWC semi-fascist uprising, Top right: Over 100,000 at Bobby Sands’ funeral. Bottom left, The Marxist stance on the Malvi- nas War, Bottom right: ‘Worker in uniform’ holds Ted Grant’s stance. “A socialist government would make a class appeal to the Argen- tinean workers. A Labour government could not just abandon the Falklanders and let Galtieri get on with it. But it would continue the war on socialist lines.” Militant International Review (Issue 22, June 1982). Page 2 The CWI and IMT: Right Centrist Heirs Of Ted Grant Where We Stand press the inevitable counter- party and trade unions revolution of private capitalist 5. We oppose all immigra- 1. WE STAND WITH profit against planned produc- tion controls. International KARL MARX: ‘The emancipa- tion for the satisfaction of so- finance capital roams the planet tion of the working classes must cialised human need. in search of profit and imperial- be conquered by the working 3. We recognise the necessity ist governments disrupts the classes themselves. The struggle for revolutionaries to carry out lives of workers and cause the for the emancipation of the serious ideological and political collapse of whole nations with working class means not a struggle as direct participants in their direct intervention in the struggle for class privileges and the trade unions (always) and in Balkans, Iraq and Afghanistan monopolies but for equal rights the mass reformist social demo- and their proxy wars in Somalia and duties and the abolition of cratic bourgeois workers’ parties and the Democratic Republic of all class rule’ (The International despite their pro-capitalist lead- the Congo, etc.