We Always Have Joy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decontextualization of Vajrayāna Buddhism in International Buddhist Organizations by the Example of the Organization Rigpa

grant reference number: 01UL1823X The decontextualization of Vajrayāna Buddhism in international Buddhist Organizations by the example of the organization Rigpa Anne Iris Miriam Anders Globalization and commercialization of Buddhism: the organization Rigpa Rigpa is an international Buddhist organization (Vajrayāna Buddhism) with currently 130 centers and groups in 41 countries (see Buddhistische Religionsgemeinschaft Hamburg e.V. c/o Tibetisches Zentrum e.V., Nils Clausen, Hermann-Balk- Str. 106, 22147 Hamburg, Germany : "Rigpa hat mittlerweile mehr als 130 Zentren und Gruppen in 41 Ländern rund um die Welt." in https://brghamburg.de/rigpa-e-v/ date of retrieval: 5.11.2020) Rigpa in Austria: centers in Vienna and Salzburg see https://www.rigpa.de/zentren/daenemark-oesterreich-tschechien/ date of retrieval: 27.10.2020 Rigpa in Germany: 19 centers see https://www.rigpa.de/aktuelles/ date of retrieval: 19.11.2019 Background: globalization, commercialization and decontextualization of (Vajrayāna) Buddhism Impact: of decontextualization of terms and neologisms is the rationalization of economical, emotional and physical abuse of people (while a few others – mostly called 'inner circles' in context - draw their profits) 2 contents of the presentation I. timeline of crucial incidents in and around the organization Rigpa II. testimonies of probands from the organization Rigpa (in the research project TransTibMed) III. impact of decontextualizing concepts of Vajrayāna Buddhism and cross-group neologisms in international Buddhist organizations IV. additional citations in German language V. references 3 I) timeline of crucial incidents in and around the organization Rigpa 1. timeline of crucial events (starting 1994, 2017- summer 2018) (with links to the documents) 2. analysis of decontextualized concepts, corresponding key dynamics and neologisms 3. -

Summer 2018-Summer 2019

# 29 – Summer 2018-Summer 2019 H.H. Lungtok Dawa Dhargyal Rinpoche Enthusiasm in Our Dharma Family CyberSangha Dying with Confidence LIGMINCHA EUROPE MAGAZINE 2019/29 — CONTENTS GREETINGS 3 Greetings and news from the editors IN THE SPOTLIGHT 4 Five Extraordinary Days at Menri Monastery GOING BEYOND 8 Retreat Program 2019/2020 at Lishu Institute THE SANGHA 9 There Is Much Enthusiasm and Excitement in Our Dharma Family 14 Introducing CyberSangha 15 What's Been Happening in Europe 27 Meditations to Manifest your Positive Qualities 28 Entering into the Light ART IN THE SANGHA 29 Yungdrun Bön Calendar for 2020 30 Powa Retreat, Fall 2018 PREPARING TO DIE 31 Dying with Confidence THE TEACHER AND THE DHARMA 33 Bringing the Bon Teachings into the World 40 Tibetan Yoga for Health & Well-Being 44 Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche's 2019 European Seminars and online Teachings THE LIGMINCHA EUROPE MAGAZINE is a joint venture of the community of European students of Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche. Ideas and contributions are welcome at [email protected]. You can find this and the previous issues at www.ligmincha.eu, and you can find us on the Facebook page of Ligmincha Europe Magazine. Chief editor: Ton Bisscheroux Editors: Jantien Spindler and Regula Franz Editorial assistance: Michaela Clarke and Vickie Walter Proofreaders: Bob Anger, Dana Lloyd Thomas and Lise Brenner Technical assistance: Ligmincha.eu Webmaster Expert Circle Cover layout: Nathalie Arts page Contents 2 GREETINGS AND NEWS FROM THE EDITORS Dear Readers, Dear Practitioners of Bon, It's been a year since we published our last This issue also contains an interview with Rob magazine. -

Dependent Origination: Seeing the Dharma

Dependent Origination: Seeing the Dharma Week Six: Interconnectedness and Interpenetration Experiential Homework Possibilities The experiential homework is essentially the first exercise we practiced in class involving looking for the boundary between oneself and other than self while experiencing seeing. This is the exercise my dissertation subjects were given for my data collection portion of my dissertation research. It relates directly to the transition from the link of nama-rupa to the link of vinnana, and then sankhara, that I spoke about in my talk this week. Just so that you can begin to have some experiential relationship to my research before I present my dissertation in our last session in two weeks, I’m including the exact instructions as they were given to my participants as well as the daily journal questionnaire they were asked to fill out. Exercises like these are meant not as onetime exercises but for repeated application. Your experience of them will often change and deepen if they are applied regularly over an extended period of time. My subjects used this exercise as part of their daily meditation practice for 15 minutes a day over a period of 10 days. Each day they filled out the questionnaire, their answers to which then became a significant part of my data. See below. Suggested Reading “Subtle Energy” This reading is a selection of excerpts from my dissertation Literature Review regarding the topic of subtle energy. See below. Transcendental Dependent Origination by Bhikkhu Bodhi. This is a sutta selection translated by Bhikkhu Bodhi with his commentary. While the ordinary form of Dependent Origination describes the causes and conditions that lead to suffering, in this version, the Buddha also enumerates the chain of causes and conditions that lead to the end of suffering. -

Mingyur Rinpoche – Detailed Biography

MINGYUR RINPOCHE – DETAILED BIOGRAPHY Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche was born in 1975 in a small Himalayan village near the border of Nepal and Tibet. Son of the renowned meditation master Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, Mingyur Rinpoche was drawn to a life of contemplation from an early age and would often run away to meditate in the caves that surrounded his village. In these early childhood years, however, he suffered from debilitating panic attacks that crippled his ability to interact with others and enjoy his idyllic surroundings. At the age of nine, Rinpoche left to study meditation with his father at Nagi Gonpa, a small hermitage on the outskirts of Kathmandu valley. For nearly three years, Tulku Urgyen guided him experientially through the profound Buddhist practices of Mahamudra and Dzogchen, teachings that are typically considered highly secret and only taught to advanced meditators. Throughout this time, his father would impart pithy instructions to his young son and then send him to meditate until he had achieved a direct experience of the teachings. When he was eleven years old, Mingyur Rinpoche was requested to reside at Sherab Ling Monastery in Northern India, the seat of Tai Situ Rinpoche and one of the most important monasteries in the Kagyu lineage. While there, he studied the teachings that had been brought to Tibet by the great translator Marpa, as well as the rituals of the Karma Kagyu lineage, with the retreat master of the monastery, Lama Tsultrim. He was formally enthroned as the 7th incarnation of Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche by Tai Situ Rinpoche when he was twelve years old. -

Films and Videos on Tibet

FILMS AND VIDEOS ON TIBET Last updated: 15 July 2012 This list is maintained by A. Tom Grunfeld ( [email protected] ). It was begun many years ago (in the early 1990s?) by Sonam Dargyay and others have contributed since. I welcome - and encourage - any contributions of ideas, suggestions for changes, corrections and, of course, additions. All the information I have available to me is on this list so please do not ask if I have any additional information because I don't. I have seen only a few of the films on this list and, therefore, cannot vouch for everything that is said about them. Whenever possible I have listed the source of the information. I will update this list as I receive additional information so checking it periodically would be prudent. This list has no copyright; I gladly share it with whomever wants to use it. I would appreciate, however, an acknowledgment when the list, or any part, of it is used. The following represents a resource list of films and videos on Tibet. For more information about acquiring these films, contact the distributors directly. Office of Tibet, 241 E. 32nd Street, New York, NY 10016 (212-213-5010) Wisdom Films (Wisdom Publications no longer sells these films. If anyone knows the address of the company that now sells these films, or how to get in touch with them, I would appreciate it if you could let me know. Many, but not all, of their films are sold by Meridian Trust.) Meridian Trust, 330 Harrow Road, London W9 2HP (01-289-5443)http://www.meridian-trust/.org Mystic Fire Videos, P.O. -

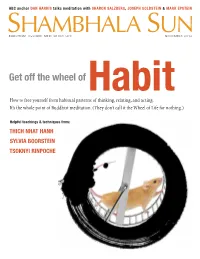

Tsoknyi Rinpoche E Whee Th L O F F F H O A

ABC anchor DAN HARRIS talks meditation with SHARON SALZBERG, JOSEPH GOLDSTEIN & MARK EPSTEIN SBUDDHISMHAMBHALA CULTURE MEDITATION LIFE SUNNOVEMBER 2014 Get off the wheel of How to free yourself from habitual patternsHabit of thinking, relating, and acting. It’s the whole point of Buddhist meditation. (They don’t call it the Wheel of Life for nothing.) Helpful teachings & techniques from: THICH NHAT HANH SYLVIA BOORSTEIN TSOKNYI RINPOCHE e Whee th l o f f f H O a t b e i t G The Natural Liberation of Habits When you recognize the true nature of mind, says Dzogchen master TSOKNYI RINPOCHE, all habitual patterns are naturally liberated in the space of wisdom. That includes the ultimate habit known as samsara. HE ULTIMATE HABITUAL PATTERN is samsara itself—the wheel of habitual cyclic existence that causes all your suffering. The karma that drives the wheel— the three poisons of attachment, aggression, and ignorance—are actually deep- seated habits of mind. TWhen you finally get tired of unconsciously participating in the daily show of habitual samsaric programming, what can you do to change it? Buddhism teaches three basic ways to cut your ties to samsara, once you have decided this is something you really need and want to do. One approach is to shut off the world of phenomena and your attachment to it. This is the path of renunciation. It is illustrated by the paintings of skeletons on the walls of temples in Burma or Thailand. They are reminders to Theravada monks and nuns to stay free of desire and attachment arising in their mind. -

Tsoknyi Rinpoche

Simply let experience take place very freely, so that your open heart is suffused with the tenderness of true compassion. ~ Tsoknyi Rinpoche Table of Contents Ordinary Refuge and Bodhicitta 1 Special Refuge 1 Four Boundless States 1 Special Bodhicitta 2 Mandala Offering 2 Requesting the Teacher to Give Teachings 2 Dedication of Merit 3 Aspirations 3 The Four Dharmas of Gampopa 4 Supplication to Guru Rinpoche 4 “Buddha of the Three Times” Long-Life Prayer for H. H. 14th Dalai Lama 5 Drubwang Tsoknyi Rinpoche’s Long-Life Supplication 5 by Adeu Rinpoche (short version) Seven Line Supplication to Guru Rinpoche 5 General Lineage Supplication (Kunzang Dorsem) 6 Supplication to the Chokling Tersar Lineage 6 (Damdzin Namtrül) Supplication to Drubwang Tsoknyi Rinpoche 8 by Adeu Rinpoche Supplication to the Root Guru 8 Supplication to the Drukpa Kagyu Lineage Masters 9 “The Staircase to the Brilliant Sumeru” by Gyalwang Kunga Paljor Ultimate Supplication 12 A Small Song of Yearning: Calling the Lama from Afar 13 A Vajra Song by Drubwang Tsoknyi Rinpoche I 15 Request for the Teacher to Remain as the 16 Vajra Body, Speech and Mind Drubwang Tsoknyi Rinpoche’s Long-Life Supplication 17 by Adeu Rinpoche (long version) One-Hundred Syllable Mantra of Vajrasattva 18 Heart Mantra of Vajrasattva 19 Prayer to Protectress Dorje Yudronma 19 1 2 Ordinary Refuge and Bodhicitta Special Bodhicitta !, ?%?- o?- (R?- .%- 5S$?- GA- 3(R$- i3?- =, ,L%- (2- 2<- .- 2.$- /A- *2?- ?- 3(A, ,2.$- A; mR$?- 0- (J/- 0R- $?J<- IA- 8/- 3- !/- 29%- ,$?- +A$- =?; ,/- 3R%- 8A- OR:A- -

Miscellaneous Great Quotes

Miscellaneous Great Quotes: Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche used to say, "Samsara is mind turned outwardly, lost in its projections; nirvana is mind turned inwardly, recognizing its nature." "Any attempt to capture the direct experience of the nature of mind in words is impossible. The best that can be said is that it is immeasurably peaceful and, once stabilized through repeated experience, virtually unshakable. It's an experience of absolute well-being that radiates through all physical, emotional and mental states - even those that might ordinarily be labeled as unpleasant." Mingyur Rinpoche “Pain and pleasure go together; they are inseparable. They can be celebrated. They are ordinary. Birth is painful and delightful. Death is painful and delightful. Everything that ends is also the beginning of something else. Pain is not a punishment; pleasure is not a reward." -Pema Chodron, When Things Fall Apart We don’t need to look outside of the present moment to find inner peace and contentment; when experienced with awareness, everything becomes of a source of joy.” Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche Meditation is about learning to recognize our basic goodness in the immediacy of the present moment, and then nurturing this recognition until it seeps into the very core of our being.” — Mingyur Rinpoche The only source of every kind of benefit for others is awareness of our own condition. When we know how to help ourselves, and how to work with our own situation…our feelings of compassion arise spontaneously, without the need to hold ourselves to the rules of behavior of any religious doctrine. ------- Nyoshul Khen Rinpoche The more that we’re at ease, the more we’re willing to open up a bit. -

NEW BOOKS> Translations and Teachings from Shambhala

H-Buddhism NEW BOOKS> Translations and Teachings from Shambhala Publications Discussion published by Nikko Odiseos on Monday, November 13, 2017 Dear Friends, I am pleased to share a set of new releases that will be of interest to many on this list. Note: All these books will be in our booth at AAR in Boston this coming weekend, stand 2313 in the middle of the hall, right next door to Columbia University Press. The Life and Visions of Yeshe Tsogyal: The Autobiography of the Great Wisdom Queen, translated by Chonyi Drolma This is a translation of a terma text discovered by Drime Kunga, then rediscovered by Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo. It included reflections from many contemporary teachers and scholars including Holly Gayley and Judith Simmer-Brown. This is a quite different text from Lady of the Lotus-Born. http://shmb.la/life-visions-yeshe-tsogyal The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa: A New Translation by Christopher Stagg "Stagg's authoritative and vibrant new translation of The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa is a marvelous achievement, at once faithful to the original Tibetan and sensitive to the modern reader. As the first complete English rendering of Milarepa’s collected poetry in more than fifty years, this edition will, no doubt, stand as the yogin’s voice for a new generation." —Andrew Quintman, associate professor of religious studies, Yale University http://shmb.la/songs-of-milarepa Changing Minds: Contributions to the Study of Buddhism and Tibet in Honor of Jeffrey Hopkins This collection includes works such as: - Tsongkhapa’s analysis of the two truths by Guy Newland - Gendun Chopel’s critique of the orthodox Gelugpa approach to Madhyamaka by Donald Lopez. -

Preparing to Die

Preparing to Die author site intro Preparing to Die 4-17-13.indd 1 4/29/13 3:49 PM author site intro Preparing to Die 4-17-13.indd 2 4/29/13 3:49 PM Preparing to Die uvWVU Practical Advice and Spiritual Wisdom from the Tibetan Buddhist Tradition Andrew Holecek Snow Lion boston & london 2013 author site intro Preparing to Die 4-17-13.indd 3 4/29/13 3:49 PM Snow Lion An imprint of Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com © 2013 by Andrew Holecek All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any infor- mation storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Excerpts from The Tibetan Book of the Dead, translated with commentary by Francesca Fremantle and Chögyam Trungpa, ©1975 by Francesca Fremantle and Chögyam Trungpa. Reprinted by arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc., Boston, MA. www.shambhala.com. Excerpts from The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying by Sogyal Rinpoche, edited by Patrick Gaffney and Andrew Harvey. Copyright © 1993 by Rigpa Fellowship. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers. Excerpts from Glimpse After Glimpse: Daily Reflections on Living and Dying by Sogyal Rinpoche. Copyright © 1995 by Sogyal Rinpoche. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers. Excerpts from Facing Death and Finding Hope by Christine Longaker, copyright © 1997 by Christine Longaker and Rigpa Fellowship. Used by permission of Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition Printed in the United States of America ♾ This edition is printed on acid-free paper that meets the American National Standards Institute z39.48 Standard. -

The Great Experiment Interview with Tim Olmsted Tricycle Magazine Fall 2010

The Great Experiment Interview with Tim Olmsted Tricycle Magazine Fall 2010 Almost thirty years ago, Tim Olmsted followed the renowned Tibetan teacher Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche to Kathmandu and became his student. Before then he had earned a masterʼs degree in psychotherapy and community organization from the University of Chicago. Now Olmsted is a dharma teacher himself. Upon returning to the United States in 1994, he settled in Colorado and founded the Buddhist Center of Steamboat Springs. From 2000 to 2003, Olmsted served as the director of Gampo Abbey, in Nova Scotia, which was founded by Tibetan nun and well-known author Pema Chödrön. Since returning to Colorado, he has continued his role as the resident teacher of the Steamboat Springs sangha. He is the president of the Pema Chödrön Foundation, established to develop the Western monastic tradition, and works closely with Tergar International, the worldwide meditation community of Tulku Urgyenʼs youngest son, Mingyur Rinpoche. Last summer, Tricycle founding editor Helen Tworkov asked Olmsted how it felt to be in the presence of Tulku Urgyen, what it was like to be a dharma bum in Nepal in the old days, and how the great dharma experiment in the West is progressing. Tell us something about going to Nepal to be with Tulku Urgyen. I arrived in Kathmandu in 1981. Many of the monasteries that had been lost in Tibet were being rebuilt in the Kathmandu Valley, so there was a tremendous amount of activity. The lamas were incredibly available, so we could spend hours talking with them. What had a huge effect on me was to see that each of those great lamas manifested differently: Some were a bit wild, talking fast and walking fast. -

{PDF} Blazing Splendor: the Memoirs of Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche Kindle

BLAZING SPLENDOR: THE MEMOIRS OF TULKU URGYEN RINPOCHE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Erik Pema Kunsang,Marcia Schmidt,Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche | 434 pages | 31 Oct 2005 | Rangjung Yeshe Publications,Nepal | 9789627341567 | English | Hong Kong, Hong Kong Blazing Splendor: The Memoirs of Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche PDF Book Tibet kurz vor dem Untergang und Szenen aus dem Exil -kein Buch hat bisher so eine perfekte Beschreibung geliefert! First, as I reflected on the letter I sent, perhaps I was too presumptuous and bold. Tulku Urgyen was uniquely positioned to know—and share with us—people who lived within this landscape of sacred values. Geri rated it it was amazing Jul 01, And then the major works of the Tibetan masters, like for instance the writings of the early Kadampa spiritual teachers. Drikung rated it it was amazing Aug 17, These cookies do not store any personal information. These translated collections still exist. Sort order. NOOK Book. Dec 14, Nate rated it it was amazing. Sebastian Kantor rated it it was amazing Aug 12, This website uses cookies to improve your experience. Candid and entertaining, each story is a spiritual gem yielding the profound wisdom that Tulku Urgyen embodied. Extremely rich and inspiring. Sadly, it was nearly extinct during the Cultural Revolution; not everyone was able to escape and save the teachings, artwork, and relics. With him is his attendant Dondrub Tara. We hear about the teachers who brought the Buddhist teachings to Tibet in the 9th century, and the unbroken line of masters who passed its secrets on through the ages. To ask other readers questions about Blazing Splendor , please sign up.