Nightmare Magazine, Issue 96 (September 2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Il Cinema Dei Fratelli Coen: Declinazioni Del Vuoto 1

Il cinema dei fratelli Coen: declinazioni del vuoto Introduzione Joel e Ethan Coen esordiscono come registi negli anni Ottanta, epoca in cui è lo stesso concetto di autore – e quindi anche quello di regista – a tornare di moda, ma al tempo stesso si trasforma: l’artista non è più creatore, ma imitatore, in un momento storico in cui si riconosce di non aver più nulla da dire. Come infatti sottolinea Buccheri, “non cerca una voce personale, ma uno stile che gli dia visibilità, un’estetica come marchio e come look – si mette in scena, offrendo il proprio corpo allo “scandalo evangelico”, in una deriva dell’autobiografismo politico degli anni Sessanta”1. E in questo giudizio di valore sono coinvolti anche i fratelli Coen che, come Brian De Palma, o Woody Allen, sono spesso stati definiti manieristi; termine inteso in questo contesto come imitatori prima che della natura, di altro cinema a sé precedente. Tuttavia, nonostante critici come Paolo Cerchi Usai abbia riportato, su “Segnocinema”, come “il loro cinema sia senza motivo, ma abbiano deciso di fare ugualmente cinema nel nome della sua inutilità”2, l’attitudine dei due registi è in realtà profondamente critica riguardo al materiale usato: dietro all’apparenza leggera infatti, si nasconde una critica radicale agli stereotipi e simboli della vita americana e in generale alla vita contemporanea, come il consumismo, la ristrettezza mentale della provincia, la ruralità, la libertà dell’arte, la controcultura stessa. I personaggi che portano in scena hanno corpi sgraziati, spesso grotteschi (si pensi a quelli interpretati da Steve Buscemi, uno degli attori feticcio del cinema dei due fratelli), e sono destinati ad un’irrimediabile alienazione, che arriva a distruggerli, persi nelle rete delle rappresentazioni e leggi sociali. -

'Ripley's Believe It Or

For Immediate Release: BELIEVE IT OR NOT, TRAVEL CHANNEL GREENLIGHTS THE REBOOT OF THE ICONIC ‘RIPLEY’S BELIEVE IT OR NOT!’ HOSTED BY ACTOR BRUCE CAMPBELL Veteran actor Bruce Campbell is executive producer and host of the reboot of “Ripley’s Believe It or Not!” NEW YORK (January 2, 2019) – Ripley’s Believe It or Not! has cornered the market on the extraordinary, the death defying, the odd and the unusual. Now, 100 years after Robert L. Ripley launched the brand, the phrase Believe It or Not! is known globally and has come to symbolize how we marvel at the wonders of our world. Travel Channel is rebooting the iconic series, hosted by veteran actor Bruce Campbell (Evil Dead, Burn Notice), with 10 all-new, one-hour episodes that will showcase the most astonishing, real and one-of-a- kind stories. Currently in production, the series will be shot on location at the famed Ripley Warehouse in Orlando, Florida, and will incorporate incredible stories from all parts of the globe — from Brazil to Baltimore. The series is slated to premiere in summer 2019. As part of the 100th anniversary celebration of Ripley’s Believe It or Not!, Campbell rang in the new year in Times Square with the New Year’s Eve Ball Drop along with millions of new friends. “As an actor, I’ve always been drawn toward material that is more ‘fantastic’ in nature, so I was eager and excited to partner with Travel Channel and Ripley’s Believe It or Not! on this new show,” said Campbell. -

American Independent Cinema

American Independent Cinema Geoff King Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgements ix Introduction: How Independent? 1 1. Industry 11 2. Narrative 59 3. Form 105 4. Genre 165 5. Alternative Visions: Social, Political and Ideological Dimensions of Independent Cinema 197 Coda: Merging with the Mainstream, or Staying Indie? 261 Notes 265 Select Bibliography 277 Index 283 Illustrations 1. Stranger Than Paradise 3 2. The Blair Witch Project 15 3. sex, lies, and videotape 35 4. Gummo 64 5. Mystery Train 94 6. Laws of Gravity 116 7. Safe 126 8. Elephant 148 9. Kill Bill Vol. 1 159 10. Martin 169 11. Reservoir Dogs 184 12. She’s Gotta Have It 212 13. Straight Out of Brooklyn 218 14. Swoon 228 15. The Doom Generation 236 Introduction How Independent? From the lowest-budget, most formally audacious or politically radical to the quirky, the offbeat, the cultish and the more conventional, the independent sector has thrived in American cinema in the past two decades, producing a body of work that stands out from the dominant Hollywood mainstream and that includes many of the most distinctive films to have appeared in the USA in recent years. It represents a challenge to Hollywood, although also one that has been embraced by the commercial mainstream to a substantial extent. Major formerly independent distributors such as Miramax and New Line are attached to Hollywood studios (Disney and Time-Warner, respectively), while some prominent directors from the independent sector have been signed up for Hollywood duty. The ‘independence’ of American independent cinema, or exactly what kind of production qualifies for the term, is constantly under question, on a variety of grounds. -

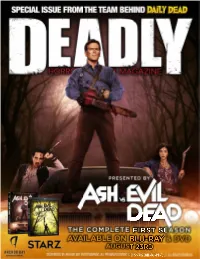

Revisiting Evil Dead

EVIL DEAD: THE BIRTH OF A FEAR FRANCHISE BY SCOTT DREBIT 4 DEADLYMAGAZINE.COM ISSUE #14 EVIL DEAD When we talk about the roots feature-length film, 1977’s rating in its theatrical release, of horror (in this case, modern) It’s Murder!, so they used guaranteeing that a large, fleshy it helps to be specific, as there Within the Woods as a calling chunk of its intended audience are so many knotty branches card to gain benefactors. It wouldn’t be allowed to see it to investigate. What is now worked, and off they went on the big screen. Home video a franchise (with three films, to Tennessee to shoot their afforded cultheads and casual a well-received remake, a gritty masterpiece. Following fans alike to savor every bit musical, and now a hit TV further financing and months of delicious grue—unless, of series, natch) started out as a of grueling shoots, the film had course, you lived in the UK, mere short film by a group of a local premiere in Detroit in where The Evil Dead shot to young, enthusiastic filmmakers ’81, before a connection of the top of their government- hoping to get investors for a Raimi’s afforded them the mandated “Video Nasties” list, feature. Now, this is a tale opportunity to dance at the effectively banning it there until that has been performed 1982 Cannes Film Festival. January of 1990, and that was for generations; from kids A fortuitous (and rapturous) after several cuts. shooting Super 8 movies in viewing at the festival by one the backyard to filming on a Stephen King ramped up the For those who haven’t seen it smartphone. -

Tobacco Product Placement and Its Reporting to the Federal Trade Commission

Tobacco product placement and its reporting to the Federal Trade Commission Jonathan R. Polansky Onbeyond LLC, Fairfax, California Stanton A. Glantz, PhD University of California, San Francisco ___________________________ University of California, San Francisco This publication is available at www.escholarship.org/uc/item/7kd981j3 July 2016 Tobacco product placement and its reporting to the FTC | 2 Summary of findings The historical record strongly suggests that asking tobacco companies to report their product placement activities and expenditures did not capture all activity in this area. This report compares expenditures for product placement described in internal documents from American Tobacco, Brown & Williamson, Liggett & Myers, Philip Morris and RJ Reynolds tobacco companies with reports the companies were required to submit to the US Federal Trade Commission in the “endorsements and testimonials” category of cigarette promotion and advertising. During that time, in their internal documents, American Tobacco, Brown & Williamson, Philip Morris and RJ Reynolds, or their contracted product placement agents, listed 750 motion pictures as engaged for product placement, 600 of which were released widely to theaters (Appendix). Substantial discrepancies exist between product placement spending described in the internal industry records and the spending reported to the Federal Trade Commission in the “endorsements and testimonials” category. Nearly half (47 percent; $2.3 million of about $5 million) of spending for on-screen product placement -

Vote Keller Vote Keller

alibi FREE VOLUME 26 | ISSUE 44 | NOVEMBER 2-8, 2017 | FREE 2017 2-8, NOVEMBER | 44 ISSUE | 26 VOLUME KEEPKEEP TRUMPIANTRUMPIAN IDEOLOGYIDEOLOGY OUTOUT OFOF THETHE MAYOR’SMAYOR’S OFFICEOFFICE VOTEVOTE KELLERKELLER PAGEPAGE 77 MARK BEYER TRANSLATES TAKE THE ABSURDIST CINEMA MIDNIGHT OPERA, THE CITY TO THE PAGE PIZZA TRAIL AND A SACRED DEER SADISTIK, NONAME PAGE 13 PAGE 18 PAGE 20 PAGE 25 NEVER MINDING THE BOLLOCKS SINCE 1992 1992 SINCE BOLLOCKS THE MINDING NEVER ARTS: FOOD: FILM: MUSIC: COUNTRY DAN’S — QUALITY, VALUE AND SERVICE SINCE 1974! FEATURING TOP NAME BRANDS! COMPLETE YOUR SUITE WITH A RECLINER, TABLE SETS AND MORE! FINANCE UP TO 5 YEARS! On approved credit. $1999 minimum purchase. Conditions and restrictions apply. Details at store. FREE SAME DAY LAYAWAY DELIVERY(1) All advertised financing is conditional on approval of credit. Financing plans are provided by third parties and the providers may change from time to time. The financing plan selected affects APR and APR is disclosed in the financing documents. Deferred payment offers and “same-as-cash” offers contain significant conditions which are disclosed in the financing documents. “Same-as-cash” financing accrues interest from the date of purchase. Interest will be waived if payment is made in full on or before the final date stipulated in the finance agreement. “No-interest” financing Montano Mon - Sat requires minimum monthly payments as stipulated in the finance agreement. Interest will be charged to your account if minimum payments are not made or if the full balance is not paid by the stipulated date. Other finance plans may be offered from time to time, with conditions and charges 1201 S. -

Export Data As PDF File

Joel Gordon, "Entry on: Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (Series, S00E05): Hercules in the Maze of the Minotaur by Sam Raimi, Robert Tapert, Christian Williams ", peer-reviewed by Elizabeth Hale and Elzbieta Olechowska. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2019). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/757. Entry version as of September 30, 2021. Sam Raimi , Robert Tapert , Christian Williams Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (Series, S00E05): Hercules in the Maze of the Minotaur TAGS: Deianeira Hera Hercules Iolaus Labyrinth Minotaur Zeus We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (Series, S00E05): Hercules in Title of the work the Maze of the Minotaur Studio/Production Company MCA Television, Renaissance Pictures Country of the First Edition New Zealand, United States of America Country/countries of USA, New Zealand, Australia popularity Original Language English Hercules in the Maze of the Minotaur. Directed by Josh Becker; written by Andrew Dettmann, and Daniel Truly. USA, (Universal) First Edition Details Action Pack Weds 8-10pm (syndicated television); 14 November 1994. 90 mins. Running time 90 mins Format TV; also VHS, DVD and digital streaming (Amazon). Date of the First DVD or VHS VHS June 17, 1997; DVD June 24, 2003 Action and adventure fiction, B films, Mythological fiction, Genre Television series Target Audience Crossover Joel Gordon, University of Otago (Classics), Author of the Entry [email protected] 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood.. -

OMC | Data Export

Joel Gordon, "Entry on: Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (Series, S01E01, S01E13): The Wrong Path / Unchained Heart by Sam Raimi, Robert Tapert, Christian Williams ", peer-reviewed by Elizabeth Hale and Lisa Maurice. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2019). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/888. Entry version as of September 26, 2021. Sam Raimi , Robert Tapert , Christian Williams Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (Series, S01E01, S01E13): The Wrong Path / Unchained Heart (1995) TAGS: Ares Centaur Cyclops / Cyclopes Dionysus Gladiator games Gods Greek mythology Hera Heracles / Herakles Hero Hero’s journey Iolaus Slavery Teiresias We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (Series, S01E01, S01E13): The Title of the work Wrong Path / Unchained Heart Studio/Production Company MCA Television, Renaissance Pictures Country of the First Edition New Zealand, United States of America Country/countries of popularity United States of America, New Zealand, Australia Original Language English First Edition Date 1995 Season 1, Episode 1. The Wrong Path. Directed by Doug Lefler; Written by John Schulian. USA, Syndicated (MCA); January 16, 1995. 44 mins. First Edition Details Season 1, Episode 13. Unchained Heart. Directed by Bruce Seth Green; Written by John Schulian. USA, Syndicated (MCA); May 8, 1995. 44 mins. Running time 44 mins. Format TV; subsequently VHS, DVD and digital streaming. Date of the First DVD or VHS VHS June 17, 1997; DVD June 24, 2003 Official Website mca.com/tv/Hercules (accessed: October 8, 2019). 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood.. -

Proquest Dissertations

WHERE LIGHT IN DARKNESS LIES: THE GROTESQUE IN THEORY AND CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN FILM A Dissertation By SCHUY R. WEISHAAR Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2010 Major Subject: English UMI Number: 3459292 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459292 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. uest ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 WHERE LIGHT IN DARKNESS LIES: THE GROTESQUE IN THEORY AND CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN FILM SCHUY R. WEISHAAR Approved: DA: Dr. David Lavery, Dissertafipn Director -c^. Dr. Linda Badley, Reader Qlk~ HAS? Dr. Allen Hibbard, Reader Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION For Felicia, Finn, Athan, and Kyle 11 ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates the work of five contemporary American filmmakers (Tim Burton, Terry Gilliam, Joel and Ethan Coen, and David Lynch) through the lens of the grotesque. Chapter I discusses the roles of genre and classical Hollywood style in the emergence of aspects of the grotesque in film history and suggests that the disintegration of the old structures of the industry, well under way by the 1960s and 70s, afforded filmmakers new opportunities to experiment with the grotesque. -

Season Two- Production Biographies

-SEASON TWO- PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES SAM RAIMI (EXECUTIVE PRODUCER) Sam Raimi has directed one the industry’s most successful film franchises ever—the blockbuster Spider-Man trilogy, which has grossed $2.5 billion at the global box office. All three films reside in the industry’s top 25 highest grossing titles of all time. In addition to the franchise’s commercial success, Spider-Man (2002) won that year’s People’s Choice Award as Favorite Motion Picture, earned a pair of Oscar® nominations (for VFX and Best Sound) and also collected two Grammy® nominations (for Best Score and Chad Kroeger’s song, “Hero”). The sequel, Spider-Man 2 (2004) won the Academy Award® for Best Visual Effects (with two more nominations, Best Sound and Sound Editing) and two BAFTA nominations (for VFX and Best Sound), among dozens of other honors. Most recently, Raimi is known for directing Oz the Great and the Powerful, a commanding prequel to one of Hollywood’s most beloved stories. Grossing nearly a quarter of a billion dollars at the worldwide box office, Oz has also been elected for awards across the board, including a nomination at the People’s Choice Awards for Favorite Family Movie, and winning Film Music at the BMI Film & TV Awards. Apart from creating one of Hollywood’s landmark film series, Raimi’s eclectic resume includes the gothic thriller The Gift, starring Cate Blanchett, Hilary Swank, Keanu Reeves, Greg Kinnear, and Giovanni Ribisi; the acclaimed suspense thriller A Simple Plan, which starred Bill Paxton, Billy Bob Thornton, and Bridget Fonda (for which Thornton earned an Academy Award® nomination for Best Supporting Actor and Scott B. -

Contained in Canadian Films

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts The Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Bc. Andrea Zajícová We the People of Canada, in Order to Form a More Perfect Union Make Canadian Films: The Representation of 'Canadianness' in Canadian Films Master´s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr. 2012 1 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. ……………………………………………. Bc. Andrea Zajícová 2 Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor – doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr. – who generously gave his advice and made comments and suggestions to improve my writing and the direction of my thesis, and who also lent me several of the secondary sources. Furthermore, I would like to thank Mgr. Radoslava Pekarová for her constant encouragement and advice; Bc. Vladimír Zán for lending me some secondary sources as well; and all my Canadian friends, especially Kevan Vogler, and their acquaintances for providing me with myriads of personal experiences, observations and views regarding the issues my thesis is concerned with. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ………………………………………………………7 1.1 Primary Sources………………………………………………………………..10 2. What is identity?............................................................................11 2.1 Distinction of identity – internal vs. external…………...................................12 2.2 Landscape identity…………………………....................................................14 2.3 Technologized identity……………………….................................................15 -

KCC Gets National Service Learning Award

International Tae kwon do master Festival revisited discusses his art API'O page 5 page 6 Volume 29 No. 28 1996 KCC gets national service learning award In June, 1994, Dr. Franco, then Edna Keeton director of KCC's AACC/Kellogg Co-editor Beacon Project, was immediately struck by the relevance of the Provost John Morton will accept AACC's national focus on service an award of excellence for the col learning as an experiential peda laborative efforts made by KCC gogy. within the service learning field dur "KCC was already committed ing the American Association of to taking higher education beyond Community Colleges Convention in the classroom as well as creating a Atlanta, April 14. campus environment that would In a nati.onal competition spon nurture an understanding and ap sored by the Campus Compact Na preciation of cultural diversity," he tional Center for Community Col said. leges, KCC has been selected as the " We were already using the college developing the "Best Col campus and the world as learning laborative Partnerships with Social environments and now service Agencies." Other categories included learning could connect to learning "Collaboration with Business and experiences in the neighborhood Industry," and "Collaboration with and community." K-Ph.D. Schools." Through his doctoral research A nomination letter submitted by on Samoan perceptions of work, Leon Richards, Dean of Instruction Dr. Franco found that to many Sa at KCC, described the development moans, work is seen as a way of of the collaboration at KCC as hav serving the family, the chief, the ing "strong service learning support village and the community.