Pilgrim Et Al.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VEGAN ORGANIC GROWING the Vegan-Organic Network

VEGAN ORGANIC GROWING The Vegan-Organic Network GUIDE Vegan-Organic Information Sheet #4 (60p) Vegan-Organic Growing - The Basics Growing with concern for people, ani- information is needed. mals and the environment Whilst conventional cultivation relies Organic growing involves treating the on synthetic chemicals and animal prod- soil, the growing environment and the ucts, traditional organic production also world environment as a resource to be generally relies on animal wastes and by- preserved for future generations, rather products. Both involve the exploitation than exploited in the short term. Vegan- of living creatures, and the inefficient use organics means doing this without any of land, water and energy resources. Ve- animal products at all, which is not dif- gan-organic methods minimise these ficult when you know how. All soil fertil- drawbacks. Many people who are not ity ultimately depends on plants and min- themselves vegan or vegetarian are com- erals - these do not have to be passed through ing to appreciate that animal-free grow- an animal in order to work. Fertility can ing is the most sustainable system: it is be maintained by plant-based composts, the future of organics. green manures, mulches, chipped branch wood, crop rotations and any other Vegan-organic information sheets are method that is sustainable, ecologically produced on various topics by the Ve- benign and not dependent upon animal gan-Organic Network, and are aimed exploitation. mainly at those with allotments, kitchen The guidelines below do not attempt gardens, or other small growing areas, to be fully comprehensive. The extent to although many of the techniques will also which you adhere to any system really de- apply to larger-scale situations. -

Sustainable Fruit Production Summary

AGROFORESTRY AND SUSTAINABLE FRUIT PRODUCTION AT HILLTOP COMMUNITY FARM, LLC PROJECT SUMMARY: Project Title: Assessing the Sustainability of Growing Non-Traditional Fruit Tree Crops in Wisconsin: A Collaborative Agroforestry Approach E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.hilltopcommunityfarm.org Summary Created by Erin Schneider & Rob McClure on May 10, 2010 updated on October 18, 2010 For a complete description of our grant project progress report including a detailed budget report, visit the NC SARE website. Overview: We are working to develop appropriate outreach materials and provide educational opportunities for growers to collaborate for producing Aronia, Russian Quince, European black currant, white and red currant, Saskatoon, Seaberry, and American Elderberry. This is part of a longer-term regional project to establish sustainable production practices, expand regional fruit grower networks, examine risk, and test consumer fruit acceptance. In addition to expanding unique varieties of Midwest – grown fruits, these species are high yielding, environmentally friendly, and are an exceptionally nutritional food source. Growing these fruits can lead to increased economic viability for small – mid-sized organic farms. Our main objectives include: 1. Find fruits that are suitable for organic production in the Midwest that can be easily grown, and have minimal labor, establishment, and management costs. The fruits should also be nutrient rich, appealing, and accessible to consumers. 2. Through our design, stimulate the use of sustainable agriculture methods that demonstrate ways to conserve moisture, build soil fertility, manage for wildlife, and reduce weed competition. 3. Provide outreach opportunities and educational resources for growers about the value and potential profitability of growing these fruits. -

Forest Garden Design

Forest garden design Indhold Context of project 2 Survey 2 Analysis 4 Forest garden basics 4 Key areas and Accessibility 5 Maintenance 5 Identifying beneficial functions and attributes 6 Companion planting 7 Design 8 Infrastructure and placement of the forest garden area 8 Soil mulching and conditioning 9 Process of choice of plants 10 Edge materials 10 Example of a guild around an apple tree 11 Nutrient calculations and budget 12 Calculating the Nutrient budget - Demands 13 Total need of nutrients from existing and new trees and shrubs 13 The overall Nutrient balance 14 Nutrient calculations for the forest garden 15 Decide 16 Additional shrubs and trees 16 Choice of smaller plants and herbs 18 Implementation plan 19 Map of forest garden 21 Diploma Criteria 22 1 | Applied Permaculture diploma Forest garden design Context of project The forest garden project will be established at the homestead Kattekærhus, on the island Orø, as part of the garden design. The forest garden will contribute to the livelihood of the occupants, namely the diploma applicant, and visitors. The forest garden is one element in a design which includes the house, the old stables, the back garden, the front garden, the backyard and the driveway, as described in the “Homestead design for Kattekærhus”. It is intended that Kattekærhus in the future will become a LAND centre. The garden will therefore be designed to be a demonstration garden as well as produce a significant contribution to the household food supply and have recreational and educational areas. The aim with the forest garden is to supplement a lifestyle which is semi-self-sufficient. -

Food Forest Plants for the West Coast

Copyright Notice Copyright 2005 Rain Tenaqiya. All images copyright 2005 Rain Tenaqiya, unless otherwise noted. Excerpts from this book may be used free of charge for nonprofitable purposes, as long as the title, author’s name, and author’s contact information is included. For business purposes, a reasonable donation would be appropriate, in addition to the above citation. The entire book may be duplicated and distributed for $10.00 a copy. Please see How to Contact the Author at the end of the book. 2 Contents Acknowledgements 4 Introduction 5 Section 1: West Coast Food Forestry 8 Special Characteristics of the West Coast 8 Food Forests of the West Coast 18 Section 2: West Coast Food Forest Plants 32 Food Forest Plant Profiles 32 Fruit and Nut Harvest Seasons 118 Plant Characteristics 121 Appendix: An Introduction to Permaculture 130 Permaculture Ethics and Principles 130 Zone and Sector Analysis 133 West Coast Permaculture Resources 135 Plant Information and Materials Sources 137 Photo Credits 139 Plant Index to Food Forest Plant Profiles 140 How to Contact the Author 143 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Gary Bornzin and the Outback Farm at Fairhaven College, Western Washington University, Bellingham, Washington, for first introducing me to Permaculture, in 1992. It was there that I saw the phrase “Plant Perennials” painted on the side of a small shack which has since been removed. I have taken the words to heart. I would also like to thank Jono Neiger and the Forest Garden at Lost Valley Educational Center, Dexter, Oregon for giving me my first opportunity to practice and teach food forestry. -

Title Author Car Care: How Is Works, How To

Title Author Car Care: How is Works, How to Look After It Automobile Association Production of wood charcoal in Great Britain Aaron, J R A Sustainable Community in the Egyptian Desert Abouleish, Ibrahim Plants, Seeds, Books & Sundries Agroforestry Research Trust Local environment journal Agyeman, Julian Ed Moving forward; program for a participatory economy Albert, Michael Encyclopedia of social inventions Albery, N. Eds. Soil Fertility & Human and Animal Health . The Albrecht Papers. Volume 8 Albrecht, William, A. Ph.D. A pattern language; towns - buildings - construction Alexander, C et al The Organic Allotment Algar, Anne Home Farm: Complete Food Self Sufficiency Allaby, Michael Growing and Preserving Fruit Allderdyce, Carthew Fresh from the Kitchen Allen, Debbi Off The Grid: Managing Independent Renewable Electricity Systems Allen, Paul Winnie-the-Pooh on management; in which a very important bear and his Allen, Roger E friends are introduced to a very important subject Agroecology: The Scientific Basis for Alternative Agriculture Altieri, Miguel Ecologies of the Heart. Emotion, Belief and the Environment Anderson, E.N Goal Directed Project Management Anderson, Erling.S, Grude, Kristoffer, V, and Haug Tor Growing and Preserving Fruit Allerdyce, Carthew Beekeeping for Beginners Richards, Andrew Creating a Wild Flower Garden Andrews, Jonathan Bike Easy: Top tips and expert advice for the new cyclist Andrews, Peter The Allotment Handbook - A guide to promoting and protecting your site. Andrews, Sophie Edible Cities: Urban Permaculture for Gardens, Yards, Balconies, Rooftops Anger, J, Fiebrig, I and Schynder, M. and Beyond Permaculture Design: A step-by-step guide Aranya The private life of plants Attenborough, David Ecosystem Geography. -

Companion Planting, Polycultures and Guilds

Companion Planting, Polycultures and Guilds Companion planting, polycultures and guilds are integral parts of permaculture growing systems. (Gardening or farming in a way that is as abundant as possible while taking care of our planet and humanity.) These methods all share in common the idea that we should value and promote diversity as much as possible, and integrate rather than segregating when it comes to growing our food. What is Companion Planting? Companion planting is simply planting at least one plant as a 'companion' to another. The central idea in companion planting is that monocultures are a bad thing. A monoculture is a plantation of just one crop (as you would typically often see in large farm fields). The problem with monocultures is that they are inherently unnatural. They take more resources (water, energy, etc.) to maintain, and can damage the soil ecosystem. And since they are more prone to problems with pests and diseases, they are harder (if not impossible) to manage organically. By carefully choosing which plants to place next to each other, we can find solutions to many of the problems that are commonly found in mono-crop systems. We know surprisingly little about the many different ways that different plants interact. But we do know that plants can help each other in a range of surprising ways. The simplest form of companion planting involves individual plants to sow and grow alongside one of our main crops. Companion plants can be dotted throughout a bed, placed with the main plant in a pot or container, or planted around the edges of a growing area. -

A Social Learning Organisation Evolves a Research Capability in Order to Study Itself

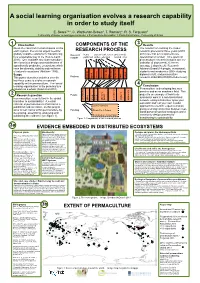

A social learning organisation evolves a research capability in order to study itself E. Sears1,2,3, C. Warburton-Brown2, T. Remiarz2, R. S. Ferguson4 1 University of Exeter ([email protected]), 2 Permaculture Association, 3 Plants For A Future, 4 University of Illinois 3 1 Introduction COMPONENTS OF THE Results Given the risks from human impacts on the The results from running the model earth system, there is an urgent need for RESEARCH PROCESS research process for three years (2010- globally scalable solutions for transitioning Research items papers conferences projects trial 2013) are that 22 components are to a sustainable way of life (Future Earth outputs published written attended funded sites operational or funded. Time spent on 2013). One available tool is permaculture: permaculture research includes one co- 'the conscious design and maintenance of ordinator (3 days/week), 6 interns agriculturally productive ecosystems which (average 3 days/week), Research have the diversity, stability and resilience e Advisory Board (14 people, occasional), y k s g r o y d m s o of natural ecosystems' (Mollison 1990). o students and academics (350+ studying t s g e y o t l b a e e s e n i t d w e s c v e diploma in UK, and permaculture o l i Scope d a s r n o r x g a d u i t i u a Projects a n t a r n s d s t research at BA/MSc/PhD/Post-doc level). k b i h t This poster describes activities over the s last three years to evolve a research capability within permaculture. -

Edible Forest Garden Permaculture for the Great Lakes Bioregion

Edible Forest Garden Permaculture For the Great Lakes Bioregion Background, Development and Future Plans for The Michigan State University Student Organic Farm Edible Forest Garden Prepared by Jay Tomczak As part of the requirements for the Masters of Science degree in Horticulture Michigan State University East Lansing, MI 48824 Copyright Protected – Not to be reproduced without the permission of the Author “We are not working with nature, we are nature working.” This project was supported in part by the USDA Risk Management Agency. The support is gratefully acknowledged. Tomczak, MSU SOF Edible Forest Garden, July 2007, pg 1 Table of Contents Topic Page No. Title Page 1 Table of Contents 2 Preface 3 Introduction 4 Section 1 Background Information and Literature Review 12 Agroforestry 12 Permaculture 15 Edible Forest Gardens and Multistrata Homegardens 19 Common Design Principles for Temperate Climates 21 Ecosystem Benefits 24 Literature Cited 27 Section 2 Development of the MSU SOF Edible Forest Garden 31 Plot Description 31 Design Process 32 Implementation and Cultural Practices 37 Plant Material Sources and Costs 44 Final Plant List and Figures for MSU SOF EFG 46 Section 3 Management and Maintenance Plan for the MSU SOF EFG 52 Season Plan 52 Long Term Plan 53 Section 4 MSU SOF EFG Pest Management 56 Principles 56 Practices 57 Considerations for Some Common Pests 59 Additional Literature 60 EFG Summary 62 Appendices 63 Frequently Asked Questions about the MSU Edible Forest Garden 64 EFG Permaculture Resources 69 Examples of Permaculture 56 Cultivar Plant List and Map 72 Site Evaluation for the SOF by Mark Shepard 75 Successional Brushland and Oak Savanna by Mark Shepard 83 End 95 Tomczak, MSU SOF Edible Forest Garden, July 2007, pg 2 Preface About the time I was working with students to develop the ideas and plans for the MSU Student Organic Farm, I was working with an off campus faith community to build a meditation and prayer labyrinth. -

Permaculture Design Notes

Permaculture Design Maestra November 21.indd 1 2020-11-24 10:59 PM Offered free download for the world community. www.permaculturedesign.earth//permaculturedesignnotes This is a work in progress, integrating feedback and new learnings. Make sure you have the newest, most updated edition. May 2021 Edition www.permaculturedesign.earth www.visionarypermaculture.com www.permaculturedesign.ca “Let’s embrace sustainability not because we fear the future. Let’s embrace sustainability because we love the things we love about right now” - Larry Santoyo This book is dedicated to the beloved World Community. We acknowledge the information in this text, passed down from pioneers of Permaculture, has deepest roots in the traditional cultures of the world. We recognize and give gratitude to all of the traditional cultures and their people as the source of permaculture and ecological knowledge. The permaculture movement is the modern expression of a lineage of earth centered understandings that is inherited from all who have come before us. We hold the deepest appreciation and thanks for all the Traditional People who have shared their wisdom and learnings from the natural world so that we can in turn reconnect and heal our relationships with ourselves, each other and the land. As settlers to the traditional territories where we reside, we are all grateful to live, work, play and help steward the land. We acknowledge that it would not be possible to be where we are without the ancestors of the land, their many contributions and sacrifices. We honour all of the living Indigenous Peoples who continue to steward the lands and carry the torch of their ancestral knowledge. -

Temperate Agroforestry: How Forest Garden Systems Combined with People-Based Ethics Can Transform Culture

sustainability Review Temperate Agroforestry: How Forest Garden Systems Combined with People-Based Ethics Can Transform Culture Paul Wartman *, Rene Van Acker and Ralph C. Martin University of Guelph, Guelph, ON N1G 2W1, Canada; [email protected] (R.V.A.); [email protected] (R.C.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 May 2018; Accepted: 27 June 2018; Published: 29 June 2018 Abstract: How can transforming monocultures to diverse polycultures address and solve the intersecting issues of our food system? This literature review offers community resources, practical examples, and academic research to support the shift away from monocultures, and the broader social contexts that encourage them, and towards food systems as part of cultures that prioritize people, water, and the land. Forest garden systems are presented as a temperate agroforestry-based food system design which make use of multiple perennial plants to meet human needs for food, medicine, fuel, and more while regenerating the environment in which they grow. There is a lack of peer-reviewed research in temperate forest garden systems, but it is gaining momentum alongside an increasing application in non-academic contexts. Combined with cultural principles that prioritize people, the land, and water over profits, forest garden systems are proposed as a pathway for meeting local community’s needs and environmental regeneration. Keywords: forest garden; temperate agroforestry; woody perennial polyculture; perennial agriculture; Indigenous; community; permaculture 1. Introduction In temperate regions of Turtle Island (known to many as the continent of North America), some areas such as Southern Ontario have largely been transformed from forest, wetland, and grassland to urban development and monoculture agriculture [1]. -

An Annotated Permaculture Bibliography Cascadia Permaculture Jude Hobbs 2/2013

1 An Annotated Permaculture Bibliography Cascadia Permaculture Jude Hobbs 2/2013 www.cascadiapermaculture.com General Permaculture Books The Ecology of Urban Habitats. Wheater, C. Philip. Routledge, Earth User’s Guide to Permaculture. Morrow, Rosemary. Simon London, 1999. Though written for a British audience, this book & Schuster, 2000. An informal introduction to permaculture by contains a wealth of information about urban ecology: an experienced teacher. succession, soils, animals, microclimates, and more. The Permaculture Handbook. Peter Bane New Society Publisher The Eternal Frontier: An Ecological History of North America and 2012. The author’s time tested experience yields to this Its Peoples. Flannery, Tim. Atlantic Monthly Press, 2001. After designer’s manual for the home gardener and farmer. writing The Future Eaters, an ecological history of Australia, Flannery was asked to write this book. Crucial reading is you The Best of Permaculture: A Collection. Lindegger and Tap, ed. want to know where we stand in the longer scale here. Nascimanere Nambour. First ~10 years of Pc. Fundamentals of Ecology. Odum, Eugene P. W. B. Saunders, The Future is Abundant. Korn, Snyder and Musick, ed. Tilth. A 1971. An early textbook on the basics of ecology, in depth. guide to sustainable agriculture; OP, needs to be re-done, the first bioregional Pc handbook. A Hierarchical View of Ecosystems. O’Neill, R. V. Princeton, 1986. An advanced look at how ecosystems function. Gaia’s Garden: A Guide to Home-Scale Permaculture. Toby Hemenway. Chelsea Green, 2009. Easy to use and understand Holistic Resource Management. Savory, Alan. Island, ‘88. The tour through the permaculture garden central work of a school of sustainability developed in parallel with permaculture. -

Annotated Biblio CPI 2011

1 An Annotated Permaculture Bibliography Cascadia Permaculture 10/2011 Jude Hobbs www.cascadiapermaculture.com General Permaculture Books Fundamentals of Ecology. Odum, Eugene P. W. B. Saunders, The Best of Permaculture: A Collection. Lindegger and Tap, ed. 1971. An early textbook on the basics of ecology, in depth. Nascimanere Nambour. First ~10 years of Pc. A Hierarchical View of Ecosystems. O’Neill, R. V. Princeton, Earth User’s Guide to Permaculture. Morrow, Rosemary. 1986. An advanced look at how ecosystems function. Simon & Schuster, 2000. An informal introduction to Holistic Resource Management. Savory, Alan. Island, ‘88. The permaculture by an experienced teacher. central work of a school of sustainability developed in parallel The Future is Abundant. Korn, Snyder and Musick, ed. Tilth. A with permaculture. Good biblio which includes personal growth. guide to sustainable agriculture; OP, needs to be re-done, the Noah’s Garden: Restoring the Ecology of Our Own Back Yards. first bioregional Pc handbook. Stein, Sara. Houghton Mifflin, 1995. A well-written and Gaia’s Garden: A Guide to Home-Scale Permaculture. Toby compelling plea for allowing nature back into our yards, full of Hemenway. Chelsea Green, 2009. Easy to use and understand natural history. tour through the permaculture garden The Origins of Order. Kauffman, Stuart. Oxford, 1994. A dense Introduction to Permaculture. Slay, Reny, and Mollison, Bill. and scholarly treatment of the ideas expressed in At Home in the Tagari 91 Tyalgum. The best intro, includes a concise listing of Universe. principles. Out of Control .Kelly, Kevin. Addison Wesley, 1994. How our Living Community. Haggard, Ben. Center for the Study of new understanding of biology is transforming both ecology and Community, 4018 Old Santa Fe Trail, Santa Fe NM, 87505.