Student Background Essays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diplomacy and the American Civil War: the Impact on Anglo- American Relations

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses, 2020-current The Graduate School 5-8-2020 Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The impact on Anglo- American relations Johnathan Seitz Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029 Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Seitz, Johnathan, "Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The impact on Anglo-American relations" (2020). Masters Theses, 2020-current. 56. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029/56 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses, 2020-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The Impact on Anglo-American Relations Johnathan Bryant Seitz A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History May 2020 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Dr. Steven Guerrier Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. David Dillard Dr. John Butt Table of Contents List of Figures..................................................................................................................iii Abstract............................................................................................................................iv Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 -

BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans

U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans BRIEFING REPORT U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20425 Official Business DECEMBER 2018 Penalty for Private Use $300 Visit us on the Web: www.usccr.gov U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSION The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, Catherine E. Lhamon, Chairperson bipartisan agency established by Congress in 1957. It is Patricia Timmons-Goodson, Vice Chairperson directed to: Debo P. Adegbile Gail L. Heriot • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are Peter N. Kirsanow being deprived of their right to vote by reason of their David Kladney race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national Karen Narasaki origin, or by reason of fraudulent practices. Michael Yaki • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution Mauro Morales, Staff Director because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice. • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to U.S. Commission on Civil Rights discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws 1331 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or Washington, DC 20425 national origin, or in the administration of justice. (202) 376-8128 voice • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information TTY Relay: 711 in respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, www.usccr.gov religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin. • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress. -

Refining the History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America: a Politico-Economic Analysis of the American Nations Austin Scharff

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Politics & Government Undergraduate Theses Spring 3-8-2016 Refining the History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America: A Politico-Economic Analysis of the American Nations Austin Scharff Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/pg_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Scharff, Austin, "Refining the History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America: A Politico-Economic Analysis of the American Nations" (2016). Politics & Government Undergraduate Theses. Paper 3. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Politics & Government Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Austin Scharff Bill Haltom Politics & Government Senior Seminar November 15, 2015 Refining the History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America: A Politico- Economic Analysis of the American Nations I am not a “political scientist” by training. I am an aspiring “political economist.” But, last spring, I wandered over to the Politics and Government Department at the University of Puget Sound and picked up Colin Woodard’s definitive work American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America. I became captivated by the book, and I have since read and re-read American Nations and numerous journal and newspaper articles that play on Woodard’s central argument—that America has never been one nation, but eleven distinct nations, each with its own set of political institutions and cultural values. -

Lives of Backcountry Children

National Park Service Ninety Six United States Department of Interior Ninety Six National Historic Site LIVES OF BACKCOUNTRY CHILDREN Traveling Trunk Ninety Six National Historic Site 1103 Hwy 248 Ninety Six, SC 29666 864.543.4068 www.nps.gov/nisi/ Dear Teacher, Ninety Six National Historic Site is pleased to provide you and your students with our Life of Backcountry Children Traveling Trunk. It will enrich your studies of life in the South Carolina Backcountry during the colonial era and the time surrounding the American Revolutionary War. It will provide you and your students with added insights into everyday life during this exciting time on the colonial frontier. Traveling trunks have become a popular and viable teaching tool. While this program was originally designed for elementary students, other classes may deem its many uses equally appropriate. The contents of the trunk are meant to motivate students to reflect on the lives of children in the backcountry of South Carolina. Through various clothing and everyday items, pastime activities, and literature, students will be able to better appreciate what the daily life of a young child was like during the late 1700s. Various lessons and activities have been included in the trunk. We encourage you to use these at your discretion, realizing of course that your school will only be keeping the trunk for two weeks. Before using the Traveling Trunk, please conduct an inventory. An inventory sheet can be found inside of the trunk with your school’s name on it. The contents of the trunk have been inspected and initialed by a NPS employee. -

American Tri-Racials

DISSERTATIONEN DER LMU 43 RENATE BARTL American Tri-Racials African-Native Contact, Multi-Ethnic Native American Nations, and the Ethnogenesis of Tri-Racial Groups in North America We People: Multi-Ethnic Indigenous Nations and Multi- Ethnic Groups Claiming Indian Ancestry in the Eastern United States Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München vorgelegt von Renate Bartl aus Mainburg 2017 Erstgutachter: Prof. Berndt Ostendorf Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Eveline Dürr Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 26.02.2018 Renate Bartl American Tri-Racials African-Native Contact, Multi-Ethnic Native American Nations, and the Ethnogenesis of Tri-Racial Groups in North America Dissertationen der LMU München Band 43 American Tri-Racials African-Native Contact, Multi-Ethnic Native American Nations, and the Ethnogenesis of Tri-Racial Groups in North America by Renate Bartl Herausgegeben von der Universitätsbibliothek der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1 80539 München Mit Open Publishing LMU unterstützt die Universitätsbibliothek der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München alle Wissenschaft ler innen und Wissenschaftler der LMU dabei, ihre Forschungsergebnisse parallel gedruckt und digital zu veröfentlichen. Text © Renate Bartl 2020 Erstveröfentlichung 2021 Zugleich Dissertation der LMU München 2017 Bibliografsche Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografe; detaillierte bibliografsche Daten sind im Internet abrufbar über http://dnb.dnb.de Herstellung über: readbox unipress in der readbox publishing GmbH Rheinische Str. 171 44147 Dortmund http://unipress.readbox.net Open-Access-Version dieser Publikation verfügbar unter: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:19-268747 978-3-95925-170-9 (Druckausgabe) 978-3-95925-171-6 (elektronische Version) Contents List of Maps ........................................................................................................ -

American Nations By: Colin Woodard

American Nations By: Colin Woodard As you read the book, answer the following questions: Introduction: pg. 5-13; 15 & 16 1. Give a brief definition of each of the eleven nations. What obvious objection must be answered? 2. What is the Doctrine of First Effective Settlement? CHAPTER 1: Founding El Norte 3. For how long have Europeans been living in the Americas? 4. On page 26, describe the standard of living of most Native Americans. 5. How does Spain’s desire to stamp out Protestantism relate to El Norte? (3 ways). Who are the mestizos? 6. On pages 29 & 30, explain why there is no self-government in El Norte. CHAPTER 2: Founding New France 7. Describe the two different approaches to creating New France. What was Champlain’s view on interacting with the Native American? What type of technologies do the French adopt from the Indians? (pg 39) 8. On page 40, it is described that by the 1660’s two-thirds of the French colonist were males. What affect DO YOU THINK this would have on New France? CHAPTER 3: Founding Tidewater 9. Describe the traditional story of Jamestown. What is the truth about Jamestown? Why did the first colonist fail so miserably? 10. What was a major difference in the way Jamestown treated Indians as opposed to how New France did? What two events saved Jamestown from economic ruin? (pg 47). 11. How did tobacco shape Tidewater society? How did Tidewater feel about the English Civil War? 12. What is the difference between Indentured Servants and African slaves? 13. -

Iroquois Council: Choosing Sides

1 Revolutionary War Unit Iroquois Council: Choosing Sides TIME AND GRADE LEVEL One 45 or 50 minute class period in Grade 4 through 8. PURPOSE AND CRITICAL ENGAGEMENT QUESTIONS History is the chronicle of choices made by actors/agents/protagonists who, in very specific contexts, unearth opportunities and inevitably encounter impediments. During the Revolutionary War people of every stripe navigated turbulent waters. As individuals and groups struggled for their own survival, they also shaped the course of the nation. Whether a general or a private, male or female, free or enslaved, each became a player in a sweeping drama. The instructive sessions outlined here are tailored for upper elementary and middle school students, who encounter history most readily through the lives of individual historical players. Here, students actually become those players, confronted with tough and often heart-wrenching choices that have significant consequences. History in all its complexity comes alive. It is a convoluted, thorny business, far more so than streamlined timelines suggest, yet still accessible on a personal level to students at this level. In this simulation, elementary or middle school students convene as an Iroquois council in upstate New York, 1777. British agents are trying to convince Iroquois nations to take their side in the Revolutionary War. They come with a lavish display of gifts. True to Iroquois tradition, women as well as men attend this council. Each student assumes the persona of a young warrior, mother, older sachem, etc. The class is presented with relevant factors to consider—the numbers, strength, and allegiances of nearby white settlers; the decisions that other Native nations have made; the British promise that Native people west of the Appalachian Mountains can keep their land. -

The Native American Occupation of Alcatraz Island: Radio and Rhetoric

Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 5 July 2019 The Native American Occupation of Alcatraz Island: Radio and Rhetoric Megan Engle University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit Part of the Cultural History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Radio Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Engle, Megan (2019) "The Native American Occupation of Alcatraz Island: Radio and Rhetoric," Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit/vol9/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit. 1.1 Introduction From November 1969 to June 1971, Native American protesters occupied Alcatraz Island, drawing attention to the unjust treatment of indigenous populations and the hardships they faced. Since the colonization of the Western Hemisphere, Amerindians have endured great injustices and difficulties. The arrival of Europeans brought about land seizures, broken treaties, massacres, and oppression for Native populations. It should be noted that the mistreatment of Native Americans is both a historical and modern problem. The rampant and perpetual abuse of Native Americans led to the marginalization and devaluation of indigenous populations. -

The American Nations, Vol. I. by C

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The American Nations, Vol. I. by C. S. Rafinesque This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The American Nations, Vol. I. Author: C. S. Rafinesque Release Date: October 14, 2010 [Ebook 34070] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE AMERICAN NATIONS, VOL. I.*** The American Nations; Or, Outlines of A National History; Of The Ancient and Modern Nations Of North and South America By Prof. C. S. Rafinesque. Volume I. Philadelphia Published by C. S. Rafinesque, No. 110 North Tenth Street. 1836 Contents Prospectus. .2 Dedication. .3 Preface. .5 Chapter I. 13 Chapter II. 28 Chapter III. 56 Chapter IV. 73 Chapter V. 87 Chapter VI. 115 Chapter VII. 153 Footnotes . 193 [i] Prospectus. Published quarterly at Five Dollars in advance for Six Numbers or Volumes, similar to this, of nearly 300 pages—each separate Number sold for one Dollar, or more when they will contain maps and illustrations. A list of Agents will be given hereafter. At present the principal Booksellers may act as such. The Names of the Subscribers will be printed in a subsequent Number. It is contemplated to conclude these annals and their illustrations in 12 Numbers or Volumes. Therefore the whole cost to subscribers will only be $10, for which a complete American Historical Library will be obtained. -

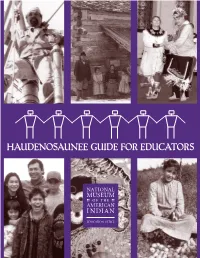

Haudenosaunee Guide for Educators

HAUDENOSAUNEE GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS EDUCATION OFFICE We gather our minds to greet and thank the enlightened Teachers who have come to help throughout the ages. When we forget how to live in harmony, they remind us of the way we were instructed to live as people. With one mind, we send greetings and thanks to these caring Teachers. Now our minds are one. From the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address Dear Educator, he Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian is pleased to bring this guide to you. It was written to help provide teachers with a better Tunderstanding of the Haudenosaunee. It was written by staff at the Museum in consultation with Haudenosaunee scholars and community members. Though much of the material contained within this guide may be familiar to you, some of it will be new. In fact, some of the information may challenge the curriculum you use when you instruct your Haudenosaunee unit. It was our hope to provide educators with a deeper and more integrated understanding of Haudenosaunee life, past and present. This guide is intended to be used as a supplement to your mandated curriculum. There are several main themes that are reinforced throughout the guide. We hope these may guide you in creating lessons and activities for your classrooms. The main themes are: Jake Swamp (Tekaroniankeken), ■ a traditional Mohawk spiritual The Haudenosaunee, like thousands of Native American nations and communities leader, and his wife Judy across the continent, have their own history and culture. (Kanerataronkwas) in their ■ The Peacemaker Story, which explains how the Confederacy came into being, is home with their grandsons the civic and social code of ethics that guides the way in which Haudenosaunee Ariwiio, Aniataratison, and people live — how they are to treat each other within their communities, how Kaienkwironkie. -

Introduction Adam Arenson

Introduction Adam Arenson The Civil War and the American West are some of the most familiar subjects in U.S. history. The journey of Lewis and Clark and the discovery of gold in California; the firing on Fort Sumter and the battle at Gettysburg; the assassination of President Lincoln and the driving of the Golden Spike to complete the transcontinental railroad—each has inspired hundreds of studies and preoccupied scholars and enthusiasts since the events themselves unfolded. But little attention has been paid to the intersections of the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the wider history of the American West, and how these seemingly separate events compose a larger, unified history of conflict over land, labor, rights, citizenship, and the limits of governmental authority in the United States. Traditionally, Civil War history has focused on the challenge of secession, the timing and reasoning behind the eradication of slavery, and the ways that large-scale military actions shaped the lives of soldiers and civilians on both sides. Histories of Reconstruction, meanwhile, have measured the promise of emancipation against the nation’s failure to achieve so many of those new possibilities. By contrast, histories of the American West have begun with the so-called frontier spaces of encounter, and have told the history of how these new territories and new peoples were integrated into European and then U.S. realms. In geographical terms, Civil War history has generally been rooted in the battlefields and plantation landscapes of the “South” (which may or may not include Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas, or other southern border states)—while the “West” of western history has most often meant the trans-Mississippi, and sometimes west of the 100th meridian. -

A Geography Lesson for the Tea Party by Colin Woodard

A Geography Lesson for the Tea Party Even as the movement’s grip tightens on the GOP, its influence is melting away across vast swaths of America, thanks to centuries-old regional traditions that few of us understand. by Colin Woodard We’re accustomed to thinking of American regionalism along Mason-Dixon lines: North against South, Yankee blue against Dixie gray or, these days, red. Of course, we all know it’s more complicated than that, and not just because the paradigm excludes the western half of the country. Even in the East, there are massive, obvious, and long-standing cultural fissures within states like Maryland, Pennsylvania, Delaware, New York, and Ohio. Nor are cultural boundaries reflected in the boundaries of more westerly states. Northern and downstate Illinois might as well be different planets. The coastal regions of Oregon and Washington seem to have more in common with each other and with the coasts of British Columbia and northern California than they do with the interiors of their own states. Austin may be the capital of Texas, but Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio are the hubs of three distinct Texases, while citizens of the two Missouris can’t even agree on how to pronounce their state’s name. The conventional, state- based regions we talk about—North, South, Midwest, Southwest, West—are inadequate, unhelpful, and ahistorical. The real, historically based regional map of our continent respects neither state nor international boundaries, but it has profoundly influenced our history since the days of Jamestown and Plymouth, and continues to dictate the terms of political debate today.