Judaism in an Anglican Theology of Interfaith Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 15: Part 5 Spring 2000

i;' 76 ;t * DERBYSHIRE MISCELLANY Volume 15: Part 5 Spring 2000 CONTENTS Page A short life of | . Charles Cor r27 by Canon Maurice Abbot The estates of Thomas Eyre oi Rototor itt the Royal Forest of the Penk 134 and the Massereene connection by Derek Brumhead Tht l'ligh Pcok I?.nil Road /5?; 143 by David lvlartin Cold!! 152 by Howard Usher Copvnght 1n cach contribution t() DtrLtyshtre Miscclkutv is reserved bv the author. ISSN 0417 0687 125 A SHORT LIFE OF I. CHARLES COX (by Canon Maudce Abbott, Ince Blundell Hall, Back O'Th Town Lane, Liverpool, L38 5JL) First impressions stay with us, they say; and ever since my school days when my parents took me with them on their frequent visits to old churches, I have maintained a constant interest in them. This became a lifelong pursuit on my 20th birthday, when my father gave me a copy of The Parish Churches ot' England by J. Charles Cox and Charles Bradley Ford. In his preface, written in March 1935, Mr Ford pointed out that Dr Cox's English Parish Church was lirsl published in 1914, and was the recognised handbook on its subiect. In time the book became out of print and it was felt that a revised edition would be appropriate, because Cox was somewhat discutsive in his writrng. The text was pruned and space made for the inclusion of a chapter on'Local Varieties in Design'. This was based on Cox's original notes on the subject and other sources. I found this book quite fascinating and as the years went by I began to purchase second-hand copies of Cox's works and eventually wanted to know more about the man himself. -

K Eeping in T Ouch

Keeping in Touch | November 2019 | November Touch in Keeping THE CENTENARY ARRIVES Celebrating 100 years this November Keeping in Touch Contents Dean Jerry: Centenary Year Top Five 04 Bradford Cathedral Mission 06 1 Stott Hill, Cathedral Services 09 Bradford, Centenary Prayer 10 West Yorkshire, New Readers licensed 11 Mothers’ Union 12 BD1 4EH Keep on Stitching in 2020 13 Diocese of Leeds news 13 (01274) 77 77 20 EcoExtravaganza 14 [email protected] We Are The Future 16 Augustiner-Kantorei Erfurt Tour 17 Church of England News 22 Find us online: Messy Advent | Lantern Parade 23 bradfordcathedral.org Photo Gallery 24 Christmas Cards 28 StPeterBradford Singing School 35 Coffee Concert: Robert Sudall 39 BfdCathedral Bishop Nick Baines Lecture 44 Tree Planting Day 46 Mixcloud mixcloud.com/ In the Media 50 BfdCathedral What’s On: November 2019 51 Regular Events 52 Erlang bradfordcathedral. Who’s Who 54 eventbrite.com Front page photo: Philip Lickley Deadline for the December issue: Wed 27th Nov 2019. Send your content to [email protected] View an online copy at issuu.com/bfdcathedral Autumn: The seasons change here at Bradford Cathedral as Autumn makes itself known in the Close. Front Page: Scraptastic mark our Centenary with a special 100 made from recycled bottle-tops. Dean Jerry: My Top Five Centenary Events What have been your top five Well, of course, there were lots of Centenary events? I was recently other things as well: Rowan Williams, reflecting on this year and there have Bishop Nick, the Archbishop of York, been so many great moments. For Icons, The Sixteen, Bradford On what it’s worth, here are my top five, Film, John Rutter, the Conversation in no particular order. -

February 2006 50P St Martin's Magazine

February 2006 50p St Martin's Magazine A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another; even as I have loved you, that you also love one another. John chapter 13 verse 34 St Martin’s Church Hale Gardens, Acton St Martin’s Church, Hale Gardens, Acton, W3 9SQ http://www.stmartinswestacton.org email: [email protected] Vicar The Revd Nicholas Henderson 25 Birch Grove, London W3 9SP. Tel: 020-8992-2333. Associate Vicar The Revd David Brammer, All Saints Vicarage, Elm Grove Road, Ealing, London W5 3JH. Tel: 020-8567-8166. Non-stipendary priest Alec Griffiths St Martin’s Cottage Hale Gardens, LondonW3 9SQ. Tel: 020-8896-9009. Parishes Secretary (9am - 2pm Monday - Friday) Parishes Office, 25 Birch Grove, W3 9SP. Tel: 020 8992 2333 Fax: 020-8932-1951 Readers Dr Margaret Jones. Tel: 020-8997-1418 Lynne Armstrong. Tel: 020-8992-8341 Churchwardens Clive Davies 1 Park Way, Ruislip Manor, Middx HA4 8PJ. Tel: 01895 -635698 John Trussler 19 Gunnersbury Crescent, Acton W3. Tel: 020-8992-4549 Treasurer - please write c/o Parishes Secretary. Director of Music – Kennerth Bartram Tel: 020-8723-1441 Sunday School – Melanie Heap Tel: 020-8993-3864 Youth Group – Michael Robinson Tel: 020-8992-7666 Womens Group - Doreen Macrae Tel: 020-8992-3907 Magazine Editor – Duncan Wigney Tel: 020-8993-3751 e-mail: [email protected] SUNDAY SERVICES 8.00 am Holy Communion 10.00 am Parish Communion& (Sunday School 6.30 pm Evensong 1st, 2nd and 3rd Sundays Taize Evening Service 4th Sunday Any Reaction? January, 2006. New Year is the time for resolutions. -

Lambeth Daily 28Th July 1998

The LambethDaily ISSUE No.8 TUESDAY JULY 28 1998 OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER OF THE 1998 LAMBETH CONFERENCE TODAY’S KEY EVENTS What’s 7.00am Eucharist Mission top of Holy Land serves as 9.00am Coaches leave University campus for Lambeth Palace 12.00pm Lunch at Lambeth Palace agenda for cooking? 2.45pm Coaches depart Lambeth Palace for Buckingham Palace c. 6.00pm Coaches depart Buckingham Palace for Festival Pier College laboratory An avalanche of food c. 6.30pm Embarkation on Bateaux Mouche Japanese Church 6.45 - 9.30pm Boat trip along the Thames Page 3 Page 4 9.30pm Coaches depart Barrier Pier for University campus Page 3 Bishop Spong apologises to Africans by David Skidmore scientific theory. Bishop Spong has been in the n escalating rift between con- crosshairs of conservatives since last Aservative African bishops and November when he engaged in a Bishop John Spong (Newark, US) caustic exchange of letters with the appears headed for a truce. In an Archbishop of Canterbury over interview on Saturday Bishop homosexuality. In May he pub- Spong expressed regret for his ear- lished his latest book, Why Chris- Bishops on the run lier statements characterising tianity Must Change or Die, which African views on the Bible as questions the validity of a physical Bishops swapped purple for whites as teams captained by Bishop Michael “superstitious.” resurrection and other central prin- Photos: Anglican World/Jeff Sells Nazir-Ali (Rochester, England) and Bishop Arthur Malcolm (North Queens- Bishop Spong came under fire ciples of the creeds. land,Australia) met for a cricket match on Sunday afternoon. -

The Magdalen Hospital : the Story of a Great Charity

zs c: CCS = CD in- CD THE '//////i////t//t/i//n///////.'/ CO « m INCOKM<i%^2r mmammmm ^X^^^Km . T4 ROBERT DINGLEY, F. R. S. KINDLY LENT BY DINGLEY AFTER THE FROM AN ENGRAVING ( JOHN ESQ.) IN THE BOARD ROOM OF THE HOSPITAL PAINTING BY W. HOARE ( I760) Frontispiece THE MAGDALEN HOSPITAL THE STORY OF A GREAT CHARITY BY THE REV. H. F. B. COMPSTON, M.A., ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OP HEBREW AT KING'S COLLEGE, LONDON PROFESSOR OF DIVINITY AT QUEEN'S COLLEGE, LONDON WITH FOREWORD BY THE MOST REVEREND THE ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY PRESIDENT OF THE MAGDALEN HOSPITAL WITH TWENTY ILLUSTRATIONS SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE LONDON: 68, HAYMARKET, S.W. 1917 AD MAIOREM DEI GLORIAM M\ FOREWORD It is a great satisfaction to me to be allowed to introduce with a word of commendation Mr. Compston's admirable history of the Magdalen Hospital. The interest with which I have read his pages will I am sure be shared by all who have at heart the well-being of an Institution which occupies a unique place in English history, although happily there is not anything unique nowadays in the endeavour which the Magdalen Hospital makes in face of a gigantic evil. The story Mr. Compston tells gives abundant evidence of the change for the better in public opinion regarding this crying wrong and its remedy. It shows too the growth of a sounder judg- ment as to the methods of dealing with it. For every reason it is right that this book should have been written, and Mr. -

Bishop Peter Hall

2 THE BRIDGE... February 2014 A view from THE BRIDGE Bishop Peter Hall . RIP Bishop Peter Hall, Ordained in 1956 Bishop Peter “I have only ever heard him family about a memorial was married with two sons. He spoken of with deep affection service in the Woolwich Area who was Bishop served in Birmingham and and appreciation especially in Bishop Michael said; “Peter of Woolwich from Zimbabwe before becoming the parishes of the Woolwich Hall brought a passionate Fresh and 1984 to 1996, Bishop of Woolwich in 1984. Episcopal Area, but also in concern for the people of the died on 28 When he retired in 1996 he Zimbabwe, where his years as Woolwich Area. Rector of Avondale in Harare traditional December 2013. returned to Birmingham “After his retirement he Diocese to serve as an are fondly remembered. continued to work for those expressions Honorary Assistant Bishop. “Indeed he played an who are excluded and Bishop Peter was a founder instrumental part in marginalised by society. His is of church of Unlock Urban Mission, establishing our companion a sad loss and he will be much former Chair of the Unlock links with the Anglican As a precocious student missed but his was a life well National Council and lynch- Church in Zimbabwe keeping lived, to the glory of God. in my early twenties pin of the annual Unlock the focus on solidarity in I wrote a piece in my “Our faith is that he is now London Walk, which he and prayer and action along with experiencing the resurrection then parish magazine his wife Jill organised for many mutual support, decrying the traditional life in which he so passionately years. -

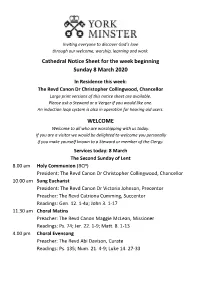

Cathedral Notice Sheet for the Week Beginning Sunday 8 March 2020

Inviting everyone to discover God’s love through our welcome, worship, learning and work. Cathedral Notice Sheet for the week beginning Sunday 8 March 2020 In Residence this week: The Revd Canon Dr Christopher Collingwood, Chancellor Large print versions of this notice sheet are available. Please ask a Steward or a Verger if you would like one. An induction loop system is also in operation for hearing aid users. WELCOME Welcome to all who are worshipping with us today. If you are a visitor we would be delighted to welcome you personally if you make yourself known to a Steward or member of the Clergy. Services today: 8 March The Second Sunday of Lent 8.00 am Holy Communion (BCP) President: The Revd Canon Dr Christopher Collingwood, Chancellor 10.00 am Sung Eucharist President: The Revd Canon Dr Victoria Johnson, Precentor Preacher: The Revd Catriona Cumming, Succentor Readings: Gen. 12. 1-4a; John 3. 1-17 11.30 am Choral Matins Preacher: The Revd Canon Maggie McLean, Missioner Readings: Ps. 74; Jer. 22. 1-9; Matt. 8. 1-13 4.00 pm Choral Evensong Preacher: The Revd Abi Davison, Curate Readings: Ps. 135; Num. 21. 4-9; Luke 14. 27-33 Services during the week Daily 7.30 am Matins (Lady Chapel) 7.50 am Holy Communion (Lady Chapel) Mon–Fri 12.30 pm Holy Communion (Lady Chapel) Saturday 12.00 pm Holy Communion (Lady Chapel) Wednesday 10.00 am Minster Mice (St Stephen’s Chapel) Thursday 7.00 pm Silence in the Minster Monday 5.15 pm Evening Prayer (Quire) Tues–Sat 5.15 pm Evensong (Quire) Services next Sunday, 15 March – Second Third of Lent 8.00 am Holy Communion (BCP) President: The Revd Dr Victoria Johnson, Precentor 10.00 am Sung Eucharist President: The Right Revd Dr Jonathan Frost, Dean Preacher: The Right Revd Tom Butler Readings: Exod. -

Leeds Diocesan Board of Finance Company Number

CONFIDENTIAL LEEDS DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE COMPANY NUMBER: 8823593 MINUTES OF A BOARD MEETING OF LEEDS DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE Held on 3rd December, 2014 at 2pm at Hollin House, Weetwood, Leeds LS16 5NG Present: The Rt Revd Dr Tom Butler (Chair), The Rt Revd Nick Baines, The Rt Revd James Bell, The Rt Revd Tony Robinson, The Ven Paul Slater, Mrs Debbie Child, The Revd Martin Macdonald, Mr Simon Baldwin, Mr Raymond Edwards, Mrs Ann Nicholl and Mrs Marilyn Banister. 1 Introduction and welcome 1.1 Noting of appointment of new directors The appointment of Mrs Ann Nicholl, Mrs Angela Byram and Mrs Marilyn Banister as directors of the company was noted. 1.2 Noting of resignation of director It was reported that John Tuckett had resigned and that as an interim measure, Debbie Child and Ashley Ellis were Joint Acting Diocesan Secretaries. Debbie Child left the meeting. Confidential Item redacted. It was also agreed that a small sub group Raymond Edwards, Simon Baldwin, Martin Macdonald and Marilyn Banister, to be chaired by Raymond Edwards, would look at the interim contracts and terms of reference for the Joint Acting Diocesan Secretaries and also consider what permanent arrangements would be needed for a diocesan secretary in the future. Initially this group would report to Bishop Nick with a view to having proposals to take to the next Diocesan Synod. It was also agreed that the group which had previously worked on the governance proposals for the diocese be re-convened and review the governance proposals in the light of the new circumstances. -

Diocesan E-News

Diocesan e-news Events Areas Resources Welcome to the e -news for December 22 A very Happy Christmas to all our readers. This is the final E-news of the year - we will be having a short break and coming back on 12 January . Meanwhile please send your news and events to [email protected] . Spreading the news with free monthly bulletin From Easter, all churches will be able to receive free copies of the four-page printed Diocesan News Bulletin, previously only available in some areas. Fifty pick-up points are being set up and every parish can order up to 500 copies each month for no cost - but December 22 Journey of the Magi we need to hear from you soon. Find out how Springs Dance Company. 7.30pm your church can receive the bulletin here. Emmanuel Methodist, Barnsley. More. Bishop Nick responds to attack in Berlin December 22 Carols in the Pub Bishop Nick writes here in the Yorkshire Post 7pm Bay Horse, Catterick Villlage. More. in response to the attack in Berlin. Over the Christmas period you can hear December 23 Carols by Bishop Nick on Radio 4's Thought for the Day Candlelight 7.30pm, Wakefield (27 December), The Infinite Monkey Cage Cathedral. More. (9am, 27 December), Radio Leeds carol service from Leeds Minster (Dec 24 & 25, times here ) and on December 23-27 Christmas Radio York on New Year's Day (Breakfast show). Houseparty & Retreat Parcevall Hall. More. Bishop Toby sleeps out for Advent Challenge December 24 Christmas Family During Advent, young people across the Nativity 11am, Ripon Cathedral. -

Leeds DBF Minutes

LEEDS DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE COMPANY NUMBER: 8823593 MINUTES OF THE BOARD MEETING OF LEEDS DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE Held on Monday, 28th April, 2014 at 2pm at 1 South Parade, Wakefield WF1 1LP Present: The Rt Revd Dr Tom Butler (Chair), Mr John Tuckett (Company Secretary), The Rt Revd Tony Robinson, The Rt Revd James Bell, The Ven Paul Slater, Mrs Debbie Child, Mr Ashley Ellis, Mr Raymond Edwards and Mr Simon Baldwin. In attendance: The Rt Revd Nick Baines, Bishop of Leeds (Designate). 1. Introduction and welcome The Rt Revd Dr Tom Butler welcomed the Board members and The Rt Revd Nick Baines, Bishop of Leeds (Designate) and opened the meeting with prayers. 2. Apologies The Revd Martin Macdonald. 3. Minutes of the meeting of the Board held on 31st March, 2014 The minutes of the meeting held on 31st March, 2014 had been circulated to the Board members prior to the meeting. No amendments were raised and the Minutes were approved. 4. Matters arising (not already on the Agenda) The Board considered the proposal for Item 8 and the matter recorded in Item 12 of the minutes of the meeting on 31st March, 2014 be redacted from publication of the minutes on the diocesan website. Agreed unanimously. The Board considered how the matters which had been discussed under Item 8 would be communicated within the Diocese. IT WAS AGREED THAT the matter would be taken to the proposed Bishop’s Council meeting for noting and communicated ad clerum from Bishop Nick for the 1st May, 2014 and that Debbie Child would provide an outline of some wording. -

The Bible and Our Times for 1963

* INCLUDED IN THIS ISSUE NOT HONEST TO GOD! TRADITION OR TRUTH? YOU CAN HAVE VICTORY OUR TIMES THE SONG OF THE HILLS By Jean P. Burnham O soft are the hills in the rising sun, And now as I stand in the cooling breeze S Blue shadows lift and the day has begun, While sunbeams dance over mountains and trees, So stirs my heart with a wondrous delight, Up to the hills I can lift my glad eyes, For a new day after darkness of night. Praising my Saviour, the Lord of the skies. So still are those hills, yet loud is their voice, How great is His art, how wise are His ways, Singing in tones that ring and rejoice: Giving to all the rich joy of new days, "God is our Maker, all glory to Him, The song of the hills can show us His love, Through endless ages, whose light ne'er grows dim." Pointing the way to our service above. This Month . .. IT is not often that a book on muim.. theology makes news headlines, but um Honest to God by Dr. John Robinson, Bishop of Woolwich, has certainly imm n caused a sensation. Its serious impli- cations for the Christian faith are mu b43 i discussed in our editorial, "Not Honest to God!"—Page 4. om A Family Journal of Christian Living. Dedi- in cated to the proclamation of the Everlasting At a time when much modern Gospel. Presenting the Bible as the Word of lm thought is seeking to banish God God and Jesus Christ as our All-Sufficient from His universe, science is pro- Saviour and Coming King. -

Download File

The Bishops of Southwark The Rt Revd Christopher Chessun The Diocese of Bishop of Southwark Southwark The Rt Revd Jonathan Clark Bishop of Croydon The Rt Revd Dr Richard Cheetham Bishop of Kingston The Rt Revd Karowei Dorgu Bishop of Woolwich 7 March 2019 To all Clergy of Incumbent Status Leaving the European Union Dear Brothers and Sisters in Christ, There are a little over three weeks now before the United Kingdom (UK) is due to leave the European Union (EU). This is a time of great uncertainty for everyone as the country waits to hear the outcome the vote due to take place in the House of Commons on Tuesday 12 March. Even when this vote has taken place it is still difficult to know how life will be here in the UK in the next weeks, months and years. At this time we want to encourage our churches and congregations to pray for unity and for people, whatever their personal views, and to come together to ensure that whatever the outcome we work together to bring about the best possible way forward for the communities we serve in Christ’s name. At a recent meeting of Diocesan clergy who are from the EU 27 remaining nations we heard powerful testimonies of the costly nature of leaving for those who have been very secure in their identity as fellow European nationals. Some have even received taunts on social media. So we commend to your prayers the healing of the divisions which have been caused by the political turmoil of the last three years.