Nick Stacey Interviewed by Louise Brodie: Full Transcript of the Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 15: Part 5 Spring 2000

i;' 76 ;t * DERBYSHIRE MISCELLANY Volume 15: Part 5 Spring 2000 CONTENTS Page A short life of | . Charles Cor r27 by Canon Maurice Abbot The estates of Thomas Eyre oi Rototor itt the Royal Forest of the Penk 134 and the Massereene connection by Derek Brumhead Tht l'ligh Pcok I?.nil Road /5?; 143 by David lvlartin Cold!! 152 by Howard Usher Copvnght 1n cach contribution t() DtrLtyshtre Miscclkutv is reserved bv the author. ISSN 0417 0687 125 A SHORT LIFE OF I. CHARLES COX (by Canon Maudce Abbott, Ince Blundell Hall, Back O'Th Town Lane, Liverpool, L38 5JL) First impressions stay with us, they say; and ever since my school days when my parents took me with them on their frequent visits to old churches, I have maintained a constant interest in them. This became a lifelong pursuit on my 20th birthday, when my father gave me a copy of The Parish Churches ot' England by J. Charles Cox and Charles Bradley Ford. In his preface, written in March 1935, Mr Ford pointed out that Dr Cox's English Parish Church was lirsl published in 1914, and was the recognised handbook on its subiect. In time the book became out of print and it was felt that a revised edition would be appropriate, because Cox was somewhat discutsive in his writrng. The text was pruned and space made for the inclusion of a chapter on'Local Varieties in Design'. This was based on Cox's original notes on the subject and other sources. I found this book quite fascinating and as the years went by I began to purchase second-hand copies of Cox's works and eventually wanted to know more about the man himself. -

February 2006 50P St Martin's Magazine

February 2006 50p St Martin's Magazine A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another; even as I have loved you, that you also love one another. John chapter 13 verse 34 St Martin’s Church Hale Gardens, Acton St Martin’s Church, Hale Gardens, Acton, W3 9SQ http://www.stmartinswestacton.org email: [email protected] Vicar The Revd Nicholas Henderson 25 Birch Grove, London W3 9SP. Tel: 020-8992-2333. Associate Vicar The Revd David Brammer, All Saints Vicarage, Elm Grove Road, Ealing, London W5 3JH. Tel: 020-8567-8166. Non-stipendary priest Alec Griffiths St Martin’s Cottage Hale Gardens, LondonW3 9SQ. Tel: 020-8896-9009. Parishes Secretary (9am - 2pm Monday - Friday) Parishes Office, 25 Birch Grove, W3 9SP. Tel: 020 8992 2333 Fax: 020-8932-1951 Readers Dr Margaret Jones. Tel: 020-8997-1418 Lynne Armstrong. Tel: 020-8992-8341 Churchwardens Clive Davies 1 Park Way, Ruislip Manor, Middx HA4 8PJ. Tel: 01895 -635698 John Trussler 19 Gunnersbury Crescent, Acton W3. Tel: 020-8992-4549 Treasurer - please write c/o Parishes Secretary. Director of Music – Kennerth Bartram Tel: 020-8723-1441 Sunday School – Melanie Heap Tel: 020-8993-3864 Youth Group – Michael Robinson Tel: 020-8992-7666 Womens Group - Doreen Macrae Tel: 020-8992-3907 Magazine Editor – Duncan Wigney Tel: 020-8993-3751 e-mail: [email protected] SUNDAY SERVICES 8.00 am Holy Communion 10.00 am Parish Communion& (Sunday School 6.30 pm Evensong 1st, 2nd and 3rd Sundays Taize Evening Service 4th Sunday Any Reaction? January, 2006. New Year is the time for resolutions. -

The Magdalen Hospital : the Story of a Great Charity

zs c: CCS = CD in- CD THE '//////i////t//t/i//n///////.'/ CO « m INCOKM<i%^2r mmammmm ^X^^^Km . T4 ROBERT DINGLEY, F. R. S. KINDLY LENT BY DINGLEY AFTER THE FROM AN ENGRAVING ( JOHN ESQ.) IN THE BOARD ROOM OF THE HOSPITAL PAINTING BY W. HOARE ( I760) Frontispiece THE MAGDALEN HOSPITAL THE STORY OF A GREAT CHARITY BY THE REV. H. F. B. COMPSTON, M.A., ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OP HEBREW AT KING'S COLLEGE, LONDON PROFESSOR OF DIVINITY AT QUEEN'S COLLEGE, LONDON WITH FOREWORD BY THE MOST REVEREND THE ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY PRESIDENT OF THE MAGDALEN HOSPITAL WITH TWENTY ILLUSTRATIONS SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE LONDON: 68, HAYMARKET, S.W. 1917 AD MAIOREM DEI GLORIAM M\ FOREWORD It is a great satisfaction to me to be allowed to introduce with a word of commendation Mr. Compston's admirable history of the Magdalen Hospital. The interest with which I have read his pages will I am sure be shared by all who have at heart the well-being of an Institution which occupies a unique place in English history, although happily there is not anything unique nowadays in the endeavour which the Magdalen Hospital makes in face of a gigantic evil. The story Mr. Compston tells gives abundant evidence of the change for the better in public opinion regarding this crying wrong and its remedy. It shows too the growth of a sounder judg- ment as to the methods of dealing with it. For every reason it is right that this book should have been written, and Mr. -

Bishop Peter Hall

2 THE BRIDGE... February 2014 A view from THE BRIDGE Bishop Peter Hall . RIP Bishop Peter Hall, Ordained in 1956 Bishop Peter “I have only ever heard him family about a memorial was married with two sons. He spoken of with deep affection service in the Woolwich Area who was Bishop served in Birmingham and and appreciation especially in Bishop Michael said; “Peter of Woolwich from Zimbabwe before becoming the parishes of the Woolwich Hall brought a passionate Fresh and 1984 to 1996, Bishop of Woolwich in 1984. Episcopal Area, but also in concern for the people of the died on 28 When he retired in 1996 he Zimbabwe, where his years as Woolwich Area. Rector of Avondale in Harare traditional December 2013. returned to Birmingham “After his retirement he Diocese to serve as an are fondly remembered. continued to work for those expressions Honorary Assistant Bishop. “Indeed he played an who are excluded and Bishop Peter was a founder instrumental part in marginalised by society. His is of church of Unlock Urban Mission, establishing our companion a sad loss and he will be much former Chair of the Unlock links with the Anglican As a precocious student missed but his was a life well National Council and lynch- Church in Zimbabwe keeping lived, to the glory of God. in my early twenties pin of the annual Unlock the focus on solidarity in I wrote a piece in my “Our faith is that he is now London Walk, which he and prayer and action along with experiencing the resurrection then parish magazine his wife Jill organised for many mutual support, decrying the traditional life in which he so passionately years. -

The Bible and Our Times for 1963

* INCLUDED IN THIS ISSUE NOT HONEST TO GOD! TRADITION OR TRUTH? YOU CAN HAVE VICTORY OUR TIMES THE SONG OF THE HILLS By Jean P. Burnham O soft are the hills in the rising sun, And now as I stand in the cooling breeze S Blue shadows lift and the day has begun, While sunbeams dance over mountains and trees, So stirs my heart with a wondrous delight, Up to the hills I can lift my glad eyes, For a new day after darkness of night. Praising my Saviour, the Lord of the skies. So still are those hills, yet loud is their voice, How great is His art, how wise are His ways, Singing in tones that ring and rejoice: Giving to all the rich joy of new days, "God is our Maker, all glory to Him, The song of the hills can show us His love, Through endless ages, whose light ne'er grows dim." Pointing the way to our service above. This Month . .. IT is not often that a book on muim.. theology makes news headlines, but um Honest to God by Dr. John Robinson, Bishop of Woolwich, has certainly imm n caused a sensation. Its serious impli- cations for the Christian faith are mu b43 i discussed in our editorial, "Not Honest to God!"—Page 4. om A Family Journal of Christian Living. Dedi- in cated to the proclamation of the Everlasting At a time when much modern Gospel. Presenting the Bible as the Word of lm thought is seeking to banish God God and Jesus Christ as our All-Sufficient from His universe, science is pro- Saviour and Coming King. -

Download File

The Bishops of Southwark The Rt Revd Christopher Chessun The Diocese of Bishop of Southwark Southwark The Rt Revd Jonathan Clark Bishop of Croydon The Rt Revd Dr Richard Cheetham Bishop of Kingston The Rt Revd Karowei Dorgu Bishop of Woolwich 7 March 2019 To all Clergy of Incumbent Status Leaving the European Union Dear Brothers and Sisters in Christ, There are a little over three weeks now before the United Kingdom (UK) is due to leave the European Union (EU). This is a time of great uncertainty for everyone as the country waits to hear the outcome the vote due to take place in the House of Commons on Tuesday 12 March. Even when this vote has taken place it is still difficult to know how life will be here in the UK in the next weeks, months and years. At this time we want to encourage our churches and congregations to pray for unity and for people, whatever their personal views, and to come together to ensure that whatever the outcome we work together to bring about the best possible way forward for the communities we serve in Christ’s name. At a recent meeting of Diocesan clergy who are from the EU 27 remaining nations we heard powerful testimonies of the costly nature of leaving for those who have been very secure in their identity as fellow European nationals. Some have even received taunts on social media. So we commend to your prayers the healing of the divisions which have been caused by the political turmoil of the last three years. -

Ordained for Ministry in Southwark Diocese

The Walking Welcoming Growing Vol.26 No.6 Newspaper of the Anglican Diocese of Southwark July/August 2021 Hands-free Curtain-up Sailing to justice Southwark launches Arts and theatre Southwark supports contactless giving return to the Diocese climate initiatives as in parishes as restrictions lift we head for COP26 See page 3 See pages 4-5 See page 12 Ordained for ministry in Southwark Diocese Twenty-four people were ordained Deacon on Saturday 26 June by the New Deacons in the Diocese of Southwark and the parishes in which they will serve Bishop of Croydon at Southwark © Cathedral (another had already been Milner Eve ordained Deacon on 9 May by the Bishop of Southwark at the Good Shepherd, Lee). The Dean of Southwark, Andrew Nunn, introduced the service, saying it was a “great day of rejoicing” both for the candidates and for all those watching the service. He also passed on Bishop Christopher’s greetings. The Venerable Mark Steadman, Archdeacon of Stow and Lindsey and formerly Chaplain to the Bishop of Southwark, preached. Speaking of the unique contribution of the Diaconate, he said: “They help us Christians to be better Henry Akingbemisilu Dr Sylvia Collins-Mayo Katie Kelly Janice Price disciples of the Lord. By their very lives, Thamesmead Team Ministry Mortlake with East Sheen St Edward the Confessor, St Andrew and St Mark, given to the Lord in his service, Deacons Jane Andrews Team Ministry Mottingham Surbiton show us how to serve, how to minister.” Putney Team Ministry Louisa Davies Capt Nicholas Lebey CA Charlotte Smith Simon Asquith St Michael and All Angels with Tolworth, Hook and Surbiton Richmond Team Ministry The candidates then made their Merton Priory Team Ministry St Stephen, Wandsworth Team Ministry Luke Whiteman declarations, after which Bishop Jonathan Dr Charles Bell Luke Demetri Carolyn Madanat Christ Church, Gipsy Hill ordained each in turn. -

Young People Join the Climate Debate at Kingston Youth Forum

The Walking Welcoming Growing Vol.26 No.5 Newspaper of the Anglican Diocese of Southwark June 2021 Parish news Justice for all Fond farewell From Pentecost How the Diocese Archdeacon of biscuits to virtual is working to Southwark leads pilgrimages combat racism goodbye service See pages 4-5 See pages 6-7 See page 12 Young people join the climate debate at Kingston Youth Forum Bishop Christopher speaks out on Palestine crisis In May, violence erupted in Israel and the West Bank while Bishop Christopher was in the Holy Land for the installation of the new Archbishop in Jerusalem, the Most Revd Hosam Naoum. “We learn a lot about climate Suggestions for looking after the brilliant to hear the young people’s change in schools. However, I think environment included remembering voices and opinions…how do we On 16 May, as the UN Security Council it should be discussed more in to switch lights off, walking or cycling embrace their prophetic challenge and met to discuss the Israel-Palestine conflict, church, so we further understand whenever possible and buying second- protest? How do we talk about the and while he was himself still in Jerusalem, Bishop Christopher spoke to BBC News how to take action against climate hand. The young people also encouraged societal, economic and political changes churches to become eco-churches, that are needed and the journey of about the situation. change” ― group feedback from the and consider solar roofing panels and conversion that we all need to go on?” Kingston Episcopal Area Youth Forum. He said: “I have heard the sound of stun better insulation. -

College of St Barnabas Patronal Festival Evensong Thursday June 9 2011 Preacher: the Bishop of Southwark, the Rt Revd Christophe

College of St Barnabas Patronal Festival Evensong Thursday June 9th 2011 Preacher: The Bishop of Southwark, The Rt Revd Christopher Chessun Beloved in Christ, today we meet as God‟s holy people to share in the life of the College of St Barnabas; it is a particular joy to me to share in these Patronal celebrations today as the College Visitor and in the first months of my public ministry as Bishop of Southwark. In sharing with you today I want to give thanks for the many years in ministry and service that are represented in all of the residents both clergy and their spouses. As we gather, together we can hear the call of the Lord, listen in the stillness and commit ourselves afresh to participate in the mission of God. The College of St Barnabas is a source of blessing both for those who live here and to the wider church to which many of the residents offer their priestly ministry in local parishes giving support to the clergy in ways which are very fruitful. The daily life of prayer within the community is a further blessing for those who are so much a part of it but also for the Diocese which is upheld and encouraged by the prayers offered each day. At the heart of the life of the Church is the constant offering of worship. And it is from our worship that everything else flows. For what we discover in worship, is that we are caught up in the vision of the heavenly kingdom on which the Book of Revelation offers us a wonderful perspective. -

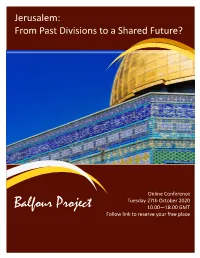

Jerusalem: from Past Divisions to a Shared Future?

Jerusalem: From Past Divisions to a Shared Future? Online Conference Tuesday 27th October 2020 Balfour Project 10.00—18.00 GMT Follow link to reserve your free place Welcome From Jerusalem : the heart of the matter Sir Vincent Fean Why Jerusalem ? It matters so much to the Israeli and Palestinian peoples, to all Jews, Christians and Muslims, and to peoples the world over. Jerusalem must be part of the solution to the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, or there will be no solution. It matters to us, the British people, whose Government contributed in large measure to the indefensible status quo. Britain ruled in Jerusalem for 31 years until 1948– and now has more influence than she cares to admit. Britain should work for inclusion – equal rights. My wife Anne and I spent three years in Jerusalem : spiritually uplifting, politically head-banging. Today there is a Jewish settlement built 50 yards from the British Consulate-General in HOW YOU occupied East Jerusalem. In a microcosm of what is happening CAN HELP elsewhere in the Holy Land, we witnessed two peoples in one APPLICATIONcity growing MANAGEMENTin separation, knowing each other less and less, despite the inevitable mingling as Jews go to pray at the The conference is free, but please Western Wall, Christians at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, consider a donation to help us keep and Muslims at al Aqsa Mosque, all in the narrow confines of going the Old City. www.peoplesfundraising.com/balfour VulputateThis conference iaceo, volutpat will eum shed mara light ut accumsan on Britain nut.’s Aliquip role in exputo the history abluo, aliquam of -project suscipitthe city euismod ; its legalte tristique status volutpat contrasted immitto with voco the abbas legal minim realities olim eros. -

Pastoral Letter from the Bishops of the Diocese of Southwark.Pdf

The Bishop of Southwark The Rt Revd Christopher Chessun The Diocese of Bishop’s House Southwark 38 Tooting Bec Gardens London SW16 1QZ To all Clergy and Churchwardens in the Diocese of Southwark t 020 8769 3256 Feast of St Thomas the Apostle, 2020 e [email protected] www.southwark.anglican.org Clergy Well-Being and the Reopening of Church Buildings Dear Brothers and Sisters in Christ, We are immensely grateful to you all for the efforts that have been made, and the imagination and creativity that have been shown, in sustaining the worshipping life of our parishes. This has taken a great many different forms, and we know that it has been welcomed and valued by congregations, as well as giving glory to God. Now we are moving into a phase where we can once again, step by step, open our church buildings for worship. This is a cause of rejoicing, but we want to say clearly that whilst some parishes will be ready to re-start public worship in the coming days, we fully realise that for others it will of necessity be a longer journey to reopening. Above all, our commitment is to ensure that our churches re-open as safely as possible. We are encouraging Clergy to factor in the need to take annual leave and consider directing congregations to online alternatives should they decide to take their leave before reopening for worship. We would encourage Deaneries to work together and co-ordinate the worship that is available both online and in churches over this period. -

The 99Th Bishop of Lichfield the Right Reverend Dr Michael Ipgrave Has St Chad, a Man of Great Humility and Profound Been Named As the Next Bishop of Lichfield

The Diocese of Lichfield Magazine Mar/Apr 2016 The 99th Bishop of Lichfield The Right Reverend Dr Michael Ipgrave has St Chad, a man of great humility and profound been named as the next Bishop of Lichfield. Christian faith.” Bishop Michael (57), the current Bishop of His appointment was announced on 2 March Woolwich in the Diocese of Southwark, will be and was greeted in Wolverhampton by Bishop the ninety-ninth Bishop of Lichfield, in a line Clive: “A year ago on St Chad’s Day, Bishop going back to St Chad in the seventh century. Jonathan announced his retirement as Bishop of Lichfield. Today, on St Chad’s Day, we can In a personal welcome message to the Diocese, share the wonderful news that Bishop Michael is Bishop Michael says “I’ve had twelve wonderful joining us here in the West Midlands. He brings years in London but I am so looking forward to with him a rare combination of gifts, as theo- coming back to the Midlands. Lichfield is the logian and teacher, pastor and mission enabler, mother church of the Midlands, and the city of which will greatly enrich our life as a Diocese.” Next to Little Drayton, to meet the Lord The Right Reverend Michael Geoffrey Ipgrave Welcome, Bishop Michael Lieutenant of Shropshire, volunteers at the OBE, MA, PhD grew up in a small village in Market Drayton Food Bank and CAP, clergy Northamptonshire. He studied mathematics Following the announce- of Hodnet Deanery chapter and the team at Oriel College, Oxford, and trained for the ment of Bishop Michael's behind the ministry at Ripon College Cuddesdon, Oxford appointment on the 10 new ‘TGI after a year working as a labourer in a factory Downing Street website, Monday in Birmingham.