Documentation/Book 2Nd WG Meeting Barcelona, LOW RESOLUTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vilafranca Del Penedès

BARCELONA VILAFRANCA DEL PENEDÈS HORARIO DE FRANQUICIA: De 8 a 14 h y de 15:45 a 20 h. Sábados cerrado, sólo entregas domiciliarias. 902 300 400 RECOGIDA Y ENTREGAS EN LOCALIDADES SIN CARGO ADICIONAL DE KILOMETRAJE SERVICIOS DISPONIBLES Alzinar, L’ Guardiola de Font Rubí Romaní SERVICIO URGENTE HOY/URGENTE BAG HOY. Arbosar de Baix, L’ Gunyoles, Les Rovellats RECOGIDAS Y ENTREGAS, CONSULTAR CON SU FRANQUICIA. Arbosar de Dalt, L’ Lavern Rovira Roja, La SERVICIO URGENTE 8:30. RECOGIDAS: Mismo horario del Servicio Avinyonet del Penedès Manantials Guardiola Sant Cugat de Sesg. Urgente 10. ENTREGAS EN DESTINO: El día laborable siguiente antes de las 8:30 h** (Consultar destinos). Bleda, La Mas Guineu, El Sant Martí Sarroca SERVICIO URGENTE 10. RECOGIDAS: Límite en esta Franquicia 20 h Bonavista Mas More (Pla Penedès) Sant Miquel d’Olèrdola destino Andorra, España, Gibraltar y Portugal. ENTREGAS EN Cabanyes, Les Moja Sant Pau d’Ordal DESTINO: El día laborable siguiente a primera hora de la mañana en Cal Via Molanta(Olèrdola) Sant Pere Andorra, España, Gibraltar y Portugal. En esta Franquicia de 8 a 10 h*. SERVICIO URGENTE 12/URGENTE 14/DOCUMENTOS 14/ Can Coral Montjüic Sant Sebastià dels Gorgs URGENTE BAG14. RECOGIDAS: Mismo horario del Servicio Urgente Cantallops Pacs del Penedès Santa Fe del Penedès 10. ENTREGAS EN DESTINO: El día laborable siguiente antes de las Cantarelles, Les Plà del Penedès Torrelles de Foix 12 h** (Urgente 12) o 14 h** (Urgente 14/Documentos 14/Urgente Canyelles Plana Rodona, La Viladellops BAG14) (Consultar destinos). SERVICIO URGENTE 19. RECOGIDAS: Límite en esta Franquicia 20 h Granada, La Puigdàlber Vilobí del Penedès destino Andorra y España peninsular. -

Pdf 1 20/04/12 14:21

Discover Barcelona. A cosmopolitan, dynamic, Mediterranean city. Get to know it from the sea, by bus, on public transport, on foot or from high up, while you enjoy taking a close look at its architecture and soaking up the atmosphere of its streets and squares. There are countless ways to discover the city and Turisme de Barcelona will help you; don’t forget to drop by our tourist information offices or visit our website. CARD NA O ARTCO L TIC K E E C T R A B R TU ÍS T S I U C B M S IR K AD L O A R W D O E R C T O E L M O M BAR CEL ONA A A R INSPIRES C T I I T C S A K Í R E R T Q U U T E O Ó T I ICK T C E R A M A I N FOR M A BA N W RCE LO A L K I NG TOU R S Buy all these products and find out the best way to visit our city. Catalunya Cabina Plaça Espanya Cabina Estació Nord Information and sales Pl. de Catalunya, 17 S Pl. d’Espanya Estació Nord +34 932 853 832 Sant Jaume Cabina Sants (andén autobuses) [email protected] Ciutat, 2 Pl. Joan Peiró, s/n Ali-bei, 80 bcnshop.barcelonaturisme.cat Estación de Sants Mirador de Colom Cabina Plaça Catalunya Nord Pl. dels Països Catalans, s/n Pl. del Portal de la Pau, s/n Pl. -

031 Sant Esteve Sesrovires LA 07 17

Direcció dels trens Horari / Horario / Timetable Dirección de los trenes / Direction of trains Sant Esteve Sesrovires Igualada R6 Notes Notas / Notes R60 Igualada . Carrilet v A rdà A rca Molí Nou es Ciutat Cooperativa es ellada rcelona r nal e Camins ovir A opa | Firarnal nellà Riera icenç delsCan Horts Ros r ovir Circula els dies feiners del mes d’agost. Ba ’Hospitalet L8 ell Enllaç Sant Esteve Pl. EspanyaMagòria IldefonsLa Campana Cer Gor Sant JosepL Almeda Cor Sant Boi Sant Esteve Eur ila | Castellbisbal Sesr allbona d’Anoia ilanova delIgualada Camí Quatr reu de la Bar V Sesr La BegudaCan Par Masquefa Piera V CapelladesLa Pobla deV Claramunt Colònia GüellSanta ColomaSant Vde Cervelló ell V ell CentralMarto r Circula los días laborables del mes r r de agosto. Pallejà Sant AndEl Palau Martor Martor Runs on weekdays in August. Sant Joan Montserrat Santa Cova Esparreguera F Circula els dissabtes i festius. Monistrol-Vila Circula los sábados y festivos. L1 L1 Runs on Saturdays and public holidays. L3 R8 ilar dis era S4 V r Abr ilador esa Alta Aparcament Autobús Autobús aeroport Aeri Funicular V r Aparcamiento Autobús Autobús aeropuerto Aéreo Funicular Cremallera esa V Manr esa Baixador Car park Bus Airport bus Cable-car Funicular de Montserrat r ol de Montserrat r icenç | Castellgalí Estació on paren tots els trens Estació on només paren alguns trens Aeri de Montserrat Castellbell Vi el Man Manr Estación donde paran todos los trenes Estación donde sólo paran algunos trenes Station where all trains stop Station where only stop some trains -

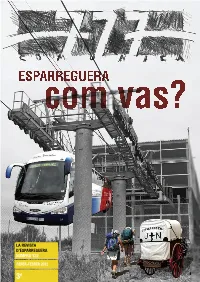

ESPARREGUERA Com Vas?

ESPARREGUERA com vas? LA REVISTA D’ESPARREGUERA NÚMERO 122 AGOST-SETEMBREGENER-FEBRER 2012 2011 3€ 1 Hem demanat als alumnes del Taller de Còmic de l’Escola d’Arts Plàstiques que ens fessin tires còmiques sobre el Transport públic, aquest n’és el resultat. Val molt la pena dedicar-hi uns minuts. 2 setsetset SUMARI 2 LA TIRA El Transport vist pels alumnes de l’Escola d’Arts Plàstiques 5 EDITORIAL La redacció SETSETSET.CAT 6 APARTAT 24 NÚMERO 122 gener-febrer 2012 600 EXEMPLARS COL·LABORACIÓ: 3 € 7 EL TEMPS ENRIC GILI Edita: Setsetset AC Apartat 24 [email protected] 8 ESPARREGUERA, 08292 Esparreguera. 93 777 84 21 COM VAS? Director: Joan Espinach Ingrid Regalado, Miguel Badajoz Consell de redacció: Miquel Altadill, Mi- i Edmon Piqué guel Badajoz,Carles Batlles, Gerard Bide- gain, Alex Casanovas, Oriol Esteve, Laura Mas, Carme Paltor, Edmon Piqué, Toni Puig, Ingrid Regalado, Carles Reynés. 14 RECULL DE PREMSA Consell d’opinió: Josep Maria Brunet, Enric Gili, Eloi Mestre, Ramon París, Jo- Oriol Esteve sep Paulo, Josep Ràfols. Opinió: Anna Valldeperas, Teresa Prats, Josep Paulo, Paquita Vives, Eduard Rivas, Carles Rey- 16 ELS SETS DEL 777 nés, Edmon Piqué, Josep Ràfols, Ade Pa- Redacció lomar i Gerard Bidegain. Col·laboració: Equip La Sargantana - Collbató. Còmic: Alumnes de Còmic Escola d’Arts Plàsti- 18 RACÓ D’HISTÒRIA ques. Fotografi a: Alumnes de fotografi a Josep Ràfols Escola d’Arts Plàstiques. Correcció: Rita Maria Vila Publicitat: 620 810 890 21 ÉS MOLT BELLA Disseny i distribució: TD’G Impressió: Gilaver LA COMARCA… Equip La Sargantana La revista 777 Comunica és membre de l’Associació Catalana de Premsa Comarcal 22 PARADA CULTURAL Gerard Bidegain La revista 777 Comunica no fa necessàriament seves les opinions ni els criteris exposats pels seus 29 VERSIÓ 2011 col·laboradors. -

There Is a Meeting in the Shadows Barriers Castelldefels - Promenade

There is a meeting in the shadows barriers Castelldefels - Promenade Carolina Annet Flores Pedro Alexander Mendoza Avila José Manuel Herrera Barbales Contemporary Landscape Projects Critique Master in Landscape Architecture Barcelona, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya Data Project: Name: Tratamiento ambiental del frente marítimo de Castellde- fels, Tramo III Castelldefels - Promonede Author(s): Cristina Saéz Talán Project date: 2013 Construction date: 2016 Budget: 2.751.806,52 € (Total), 83,50 €/m² Collaborators: Joan Roca Bastús Jordi Bardolet Sole Carles Villasur Millan Jonatan Álvarez Peña Cinta Alegre Chavarria Olga Salve Ruiz ‘‘Dialogue as an opening to discover people and territory’’ There is a meeting in the shadows barriers Carolina Annet Flores Peña Pedro Alexander Mendoza Avila Castelldefels - Promenade José Manuel Herrera Bardales HOW IS A BEACHSCAPE? ... KNOWING THE TERRITORY Barcelona a city from the Catalonia community, is loca- The strength of the wind and the force of the sea con- ted on the Northeastern coast of the Me¬diterranean tributed in the formation of the Llobregat river. This river and French Pyrenees. The city details the large moun- started its course in the Sant Boi and Prat, gaining the tain areas that generate a great natural diversity within form of the Garraf coast and separating it from the Mur- the territory, perceiving a connection between the na- trassa sea. Consequently the pond of the Murtrassa tural, sea and mountain within the urban. Although it started to be filled up with little streams transforming offers many tourist and entertainment places for people them into the Delta de Llobregat. around the world, but there is a very monotonous per- In the 20th centuries, the delta sea front, became one ceptions about the territory. -

TER a G3.Pdf

Representació Territorial de Barcelona de la Federació Catalana de Tennis Taula C/Duquessa d'Orleans, 29 int. Tel: 93 280 27 38 o 93 280 03 00 extensió 4 [email protected] www.rtbtt.com Temp. 20/21 3a "A" Grup 3 Fase 1 Equip EJ EG EE EPPG PP CdE Pts 1CTT VALLS DE TORROELLA 12111 0 62 10 0 23 2TARINAS CALELLA 1281 3 47 25 0 17 3AGRUPACIÓ CONGRÉS 1272 3 47 25 0 16 4CTT SENTMENAT 1262 4 43 29 0 14 5CTT RIPOLLET 1242 6 28 44 0 10 6CETT ESPARREGUERA 1220 10 18 54 0 4 7TT SANT ANDREU "A" 1200 12 7 65 0 0 Preguem tingueu en compte les notificacions al final del calendari. Gràcies. CONCENTRACIÓ: 1 CONCENTRACIÓ: 1 21/03/21 SEU: CTT VALLS DE TORROELLA Jornada 1 1a volta Acta 21/03/2109:00 CTT VALLS DE TORROELLA785 TT SANT ANDREU "A" 6 0 21/03/21 09:00 DESCANSA 786 CTT SENTMENAT Jornada 2 Acta 21/03/2111:30 CTT VALLS DE TORROELLA789 CTT SENTMENAT 4 2 21/03/21 11:30 DESCANSA 790 TT SANT ANDREU "A" CONCENTRACIÓ: 1 21/03/21 SEU: SURIS CALELLA Jornada 1 1a volta Acta 21/03/2109:00 CETT ESPARREGUERA787 AGRUPACIÓ CONGRÉS 0 6 21/03/2109:00 TARINAS CALELLA788 CTT RIPOLLET 5 1 Jornada 2 Acta 21/03/2111:30 CETT ESPARREGUERA791 CTT RIPOLLET 2 4 21/03/2111:30 TARINAS CALELLA792 AGRUPACIÓ CONGRÉS 1 5 CONCENTRACIÓ: 2 CONCENTRACIÓ: 2 27/03/21 SEU: CTT RIPOLLET Jornada 3 Acta 27/03/2115:30 AGRUPACIÓ CONGRÉS795 CTT SENTMENAT 4 2 27/03/2115:30 CTT RIPOLLET796 TT SANT ANDREU "A" 4 2 Jornada 4 Acta 27/03/2118:00 CTT RIPOLLET799 CTT SENTMENAT 3 3 27/03/2118:00 AGRUPACIÓ CONGRÉS800 TT SANT ANDREU "A" 5 1 Representació Territorial de Barcelona de la Federació Catalana de Tennis Taula C/Duquessa d'Orleans, 29 int. -

Esparreguera

www.igualadina.net Tél. 902.29.29.00 GUIMERÀ - BARCELONA Castelloli El Bruc Font del Codol (Collbató) Collbató Les Borges Borges Les Blanques Arbeca Belianes Maldà (emb.) Sant de Martí Maldá de Rocafort Vallbona (emb.) (emb.) Nalec Ciutadilla (emb.) Centre Guimerà Vallfogona (centre) Vallfogona (Balneari) Albió Savalla Conesa Segura Llorac Rauric Coloma Santa de Queralt Aguiló Pobla de Caribenys Els Plans de Ferran Heucària Sant de Martí Tous Saio Igualada Estac.Autob. Esparreguera Pl.Rebato Abrera Martorell Hosp.Psquiatric ZonaBcn Universitaria Palau Barcelona Reial Barcelona MªCristina Sants Barcelona DILLUNS, DIMECRES I DIVENDRES FEINERS, excepte agost, Nadal (del 26/12 al 31/12) i Dijous Sant 5.45(2) 5.50(2) 5.58(2) 6.00(2) 6.03(2) 6.05(2) 6.07(2) 6.09(2) 6.20 6.22 6.23 6.26 - - - 6.28 6.29 6.45 6.49 6.53 6.55 7.00 7.00 7.10 7.30 7.38 7.45 7.50 7.50 7.55 8.00 - 8.30 8.32 8.35 - - - - - - - - - 13.05 13.10 13.13 13.16 - - - 13.18 13.29 13.35 13.39 13.43 13.45 13.50 - 14.05 14.30 14.38 - 14.50 14.50 14.55 15.00 - 15.30 15.32 15.35 - DIMARTS I DIJOUS FEINERS, excepte agost, Nadal (del 26/12 al 31/12) i Dijous Sant 5.45(2) 5.50(2) 5.58(2) 6.00(2) 6.03(2) 6.05(2) 6.07(2) 6.09(2) 6.20 6.22 6.23 6.26 6.26 6.27 6.27 - 6.29 6.45 6.49 6.53 6.55 7.00 7.00 7.10 7.30 7.38 7.45 7.50 7.50 7.55 8.00 - 8.30 8.32 8.35 - - - - - - - - - 13.05 13.10 13.13 13.16 - - - 13.18 13.29 13.35 13.39 13.43 13.45 13.50 - 14.05 14.30 14.38 - 14.50 - 14.55 15.00 - 15.30 15.32 15.35 - DE DILLUNS A DIVENDRES FEINERS, Agost, Nadal (del 26/12 al 31/12) i Dijous Sant. -

Club De Basquet Esparreguera

Calendari Mensual Club CLUB DE BASQUET ESPARREGUERA Data i hora Partit com a LOCAL Categoria 05-03-2022 16:00 TENEA*TALENT - C.B. ESPARREGUERA - NUBEM TELECOM BÀSQUET BERGA C.C. SEGONA CATEGORIA MASC. Instal·lació: PAVELLO RAMON MARTI (HOSPITAL, 37 (08292)) 05-03-2022 20:00 PRONCAT - C.B. ESPARREGUERA - IPAE ENGINYERS - CB SANT JUST C.C. SOTS-25 MASCULI A Instal·lació: PAVELLO RAMON MARTI (HOSPITAL, 37 (08292)) 06-03-2022 12:30 AUTOESCOLA BARDÉS - C.B. ESPARREGUERA - JOVENTUT LES CORTS INTER C.C. JUNIOR MASC. INTERTERIT. Instal·lació: PAVELLO RAMON MARTI (HOSPITAL, 37 (08292)) 12-03-2022 16:30 SERVIMPRESA - C.B. ESPARREGUERA - CB LA MERCÈ C.C. JUNIOR FEM. NIVELL A Instal·lació: PAVELLO RAMON MARTI (HOSPITAL, 37 (08292)) 12-03-2022 18:00 CLEVERTASK - C.B. ESPARREGUERA - C.B VILADECAVALLS C.C. TERCERA CATEGORIA FEM Instal·lació: PAVELLO RAMON MARTI (HOSPITAL, 37 (08292)) 19-03-2022 16:00 TENEA*TALENT - C.B. ESPARREGUERA - ARENES BELLPUIG CB BELLPUIG C.C. SEGONA CATEGORIA MASC. Instal·lació: PAVELLO RAMON MARTI (HOSPITAL, 37 (08292)) 19-03-2022 20:00 PRONCAT - C.B. ESPARREGUERA - ASME C.C. SOTS-25 MASCULI A Instal·lació: PAVELLO RAMON MARTI (HOSPITAL, 37 (08292)) 20-03-2022 12:30 AUTOESCOLA BARDÉS - C.B. ESPARREGUERA - CLUB NATACIO TERRASSA A C.C. JUNIOR MASC. INTERTERIT. Instal·lació: PAVELLO RAMON MARTI (HOSPITAL, 37 (08292)) 26-03-2022 16:30 SERVIMPRESA - C.B. ESPARREGUERA - CB. CORNELLÀ 05 C.C. JUNIOR FEM. NIVELL A Instal·lació: PAVELLO RAMON MARTI (HOSPITAL, 37 (08292)) 26-03-2022 18:00 CLEVERTASK - C.B. -

2 STSM at Barcelona Metropolitan Region, February/March 2013

Short Term Scientific Missions 14/12/2012 Call for applications: Barcelona 2013 page 1/3 Call for applications 2 STSM at Barcelona Metropolitan Region, February/March 2013 COST Action Urban Agriculture Europe proposes 2 Short Term Scientific Missions (STSMs) preceding the 2nd Working Group Meeting of the Action in Castelldefels (Barcelona). All Early Stage Researchers registered in the Action are invited to submit their application for one of the STSMs until 10/01/2013. Research subject and program All COST UAE Working Group Meetings focus on one of the Action’s WG subjects and give the possibility to the WG members to discuss their work in progress with the other participants of the action. To ground this discussion, Urban Agriculture in the visited reference region will be presented in field trips and by local stakeholders. This will be made possible by the local organizer and prepared by Early Stage Researchers who have visited the region and its stakeholders on a Short-Term Scientific Mission (STSM) before.” (See MoU,p.14). The subject of the STSMs in Barcelona Metropolitan Region is to work on typologies of Urban Agriculture that can be found in the reference region as a preview to prepare the Working Groups Meeting to be held from 12th to 15th March, 2013 at the ESAB (Escola Superior d’Agricultura de Castelldfels) from the UPC (Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya) at Castelldefels (Barcelona). Program Possible field visits and interviews with managers and / or stakeholders from: - Parc Agrari del Baix Llobregat (Baix Llobregat Agrarian Park) - Parc Agrari de Sabadell (Sabadell Agrarian Park) - Consorci de l’Espai Rural de Gallecs (Consortium of Rural Gallecs) - Alella Vineyards area - Social Urban allotments and occupied horticulture ( along rivers, motorways or sloped wasted lands) in / between the cities (Barcelona / Sabadell). -

Cursa Popular 2013

XXXII Cursa Popular Castellar del Vallès 7 de setembre de 2013 Cursa Grans 5 Km LLOC DORSALNOM SEXE POBLACIO CLUB CURSA PREMI 1 261TORRENS TEIXIDOR, Jordi M Castellar del Vallès J.A.Sabadell GRANS 1 GENERAL MASCULÍ 2 66VACA LOPEZ, Manel M Castellar del Vallès Club Atlètic Castellar GRANS 2 GENERAL MASCULÍ 3 44JIMENEZ CALVO, Jordi M Castellar del Vallès no GRANS 3 GENERAL MASCULÍ 4 243GARCIA RAMON , Lluis M Terrassa Club Atlètic Castellar GRANS 4 GENERAL MASCULÍ 5 299PLAZA PEREZ, Oscar M Igualada no GRANS 5 GENERAL MASCULÍ 6 300PLAZA PEREZ, RAUL M Igualada no GRANS 7 325NOSAS GARCIA, Ignaci M Sabadell no GRANS 8 265 LOPEZ ACENEL, Jose Javier M Castellar del Vallès C.N. Caldes GRANS 1 LOCAL MASCULÍ 9 67 ORTIGOSA CLAVERIA, Albert M Castellar del Vallès Club Atlètic Castellar GRANS 2 LOCAL MASCULÍ 10 151 ESTEBANELL DESCARREGA, Xavier M Castellar del Vallès Club Atlètic Castellar GRANS 3 LOCAL MASCULÍ 11 218 SURROCA MARTINEZ, Josep M Castellar del Vallès Club Atlètic Castellar GRANS 4 LOCAL MASCULÍ 12 406RUSIÑOL TRILLO, Manel M Castellar del Vallès Club Atlètic Castellar GRANS 5 LOCAL MASCULÍ 13 55LOSADA PEREZ, Joan M Castellar del Vallès no GRANS 14 48GALLEGO VALLE, Marc M Castellar del Vallès no GRANS 15 262MAÑOSA QUEROL, Jordi M Sabadell Juventud Atletica Sabadell GRANS 16 416 MARGALEF MARTÍNEZ, Josep M Castellar del Vallès Club Atlètic Castellar GRANS 17 288ALOT MARIN, Eliseo M Castellar del Vallès no GRANS 18 320DE LA VEGA BLANCH, David M La Llagosta no GRANS 19 85MURCIA ARCAS, Javi M Castellar del Vallès Club Atlètic Castellar GRANS 20 414URREA RIVAS, Víctor M Sentmenat no GRANS 21 172MILLA SANCHEZ, David M Castellar del Vallès no GRANS 22 89 MARTI DE LOS REYES, Jonatan M Castellar del Vallèsno GRANS 23 102GARCIA CASTRO, Daniel M Castellar del Vallès Club Atlètic Castellar GRANS 24 412TALÓ ORPINELL, Marc M Castellar del Vallès no GRANS 25 380DAVID RAMIA, Daniel M Castellar del Vallès no GRANS 26 386ACUÑA ALIAS, Adrián M Castellar del Vallès no GRANS 27 160GOMEZ DOMENECH, Dani M Castellar del Vallès Club Atlètic Castellar GRANS 28 159BEJAR JIMENEZ. -

Els Serveis I Equipaments Municipals Articulen L’Activitat Social De La Vila Pàg

EL MASNOU Informació municipal i ciutadana Març 2015 VIU Núm. 74 (3a època) Els serveis i equipaments municipals articulen l’activitat social de la vila Pàg. 4-5 Reconeixement per la El 26 de març es presenten La Casa de Cultura tasca feta a l’administració les obres del Parc Vallmora i torna a obrir les portes electrònica l’ampliació del Complex Esportiu al públic el 29 de març Pàg. 7 Pàg. 10 Pàg. 20 i 21 Tots els tractaments i les últimes tecnologies Odontologia · Ortodòncia · Odontologia conservadora · Endodòncia · Periodòncia · Estètica dental · Pròtesis dentals · Implants dentals · Odontopediatria · TAC dental (Finançament a 12 mesos sense interessos) Fisioteràpia · Gimnàstica hipopressiva · Fisioteràpia esportiva · Reeducació del sòl pèlvic · Preparació pre i postpart · Incontinència urinària · Pilates Celebrem el nostre 1r Passeig Romà Fabra, 31 - El Masnou Tel. 930 084 154 - www.clinicafio.com aniversari Segueix-nos a Facebook 2 Pere Parés CARTA DE TELÈFONS D’INTERÈS Alcalde L’ALCALDE INFORMACIÓ Ajuntament Mercat Municipal Regeneració de les platges del Maresme 93 557 17 00 93 557 17 71 Àrea de Manteniment Museu Municipal i Serveis de Nàutica Finalment, el Ministeri de Medi Ambient ha anunciat una solució esperada –i desitjo que sigui 93 557 16 00 93 557 18 30 definitiva– per a la recuperació i consolidació de les platges de la costa del Maresme. Àrea de Promoció Oficina Local d’Habitatge Al Masnou aquest problema afecta principalment al sector de la platja en ambdós extrems Econòmica 93 557 16 41 del terme municipal: la d’Ocata, al sector de llevant, i la del Masnou, al sector de ponent. -

Pla D'ordenació Urbanística Municipal (Poum 2004)

PLA D’ORDENACIÓ URBANÍSTICA MUNICIPAL ESPARREGUERA Avanç de Pla VOLUM 1: Memòria URBAMED, SLP Octubre 2.014 Pla d’OrdenacióUrbanística Municipal de Esparreguera - Avanç de Pla - Equip de redacció: URBANISME INTEGRAL I MEDIAMBIENT,S.L.P. Director del treball Eduard Fenoy Palomas. arquitecte. Coordinació Mireia Salvans Soley. arquitecta. Planejament urbanístic. Marta Vivet Escalé, enginyera de l'edificació Marc Fenoy Garriga, enginyer de l'edificació Participació ciutadana INDIC, Iniciatives i dinàmiques comunitàries. Marc Majós Cullell, politòleg. Avaluació Ambiental Phragmites SL. Anàlisi socioeconòmica. Joan Angelet Cladellas, economista. Assessorament jurídic Jordi Panadès Dalmases,advocat. COMISSIÓ DE DIRECCIÓ DELS TREBALLS Eduard Fenoy Palomas. arquitecte Anna Alonso Juste, assessora jurídica de serveis territorials Francesc Balañà Comas, arquitecte municipal Josep Rovira Tarragó, regidor d’urbanisme i habitatge COMISSIÓ INFORMATIVA D'URBANISME. Joan Paül Udina Tormo Presideix la comissió Josep Santiveri Ros representant de CIU Josep Rovira Tarragó representant d'AM-ERC Ignasi Oleart Comellas representant d'AIESPA Eduard Prat Arnalte regidor no adscrit Iñaki Andrés Garralaga representant d'ICV Carlos Garcia Llevet representant del PP Eduard Rivas Mateo representant del PSC Gustau Pérez Altirriba representant de Gd'E Antonio Cañizares Martínez representant d'IRS Sergi Hidalgo Fernández regidor no adscrit 3 Pla d’OrdenacióUrbanística Municipal de Esparreguera - Avanç de Pla - ÍNDEX REVISIÓ DEL PROGRAMA D'ACTUACIÓ I MODIFICACIONS PUNTUALS