Canterbury Christ Church University's Repository of Research Outputs Http

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir William and Lady Ann Brockman of Beachborough, Newington by Hythe

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society SIR WILLIAM AND LADY ANN BROCKMAN OF BEACHBOROUGH, NEWINGTON BY HYTHE. A ROYALIST FAMILY'S EXPERIENCE OF THE CIVIL WAR GILES DRAKE-BROCKMAN A brief note in the 1931 volume ofArchaeologia Cantiana describes how a collection of papers belonging to the Brockman family of Beachborough, Newington by Hythe, had come to light and been presented to the British Library-.1 Tlie most illustrious member of this family was Sir William Brockman (1595-1654). Sir William had attended the Middle Temple in London (although it is not known if he qualified as a lawyer) and went on to hold a significant position in county society in Kent including being appointed Sheriff in 1642 (but see below). However he is best known for the noble part he played on the Royalist side in the Battle of Maidstone in 1648. In fact. Sir William's involvement in hostilities against Parliament had begun much earlier, soon after the Civil War broke out. The king had raised his standard at Nottingham and formally declared war against the Parliamentarians on 22 August 1642. The first b a t t l e took place at Edgehill in September 1642 with the Royalists gaining victory. However, when the king's anny advanced on London it was met by a large defence force and in mid-November the king withdrew to Oxford. It was at this point that Brockman endeavoured to raise a rebellion against Parliament in Kent. He was sent a commission of array by the king at Oxford while the earl of Tlianet was despatched with a regiment through Sussex to support Mm. -

St Catherine's College Oxford

MESSAGES The Year St Catherine’s College . Oxford 2013 ST CATHERINE’S COLLEGE 2013/75 MESSAGES Master and Fellows 2013 MASTER Susan C Cooper, MA (BA Richard M Berry, MA, DPhil Bart B van Es (BA, MPhil, Angela B Brueggemann, Gordon Gancz, BM BCh, MA Collby Maine, PhD California) Tutor in Physics PhD Camb) DPhil (BSc St Olaf, MSc Fellow by Special Election Professor Roger W Professor of Experimental Reader in Condensed Tutor in English Iowa) College Doctor Ainsworth, MA, DPhil, Physics Matter Physics Senior Tutor Fellow by Special Election in FRAeS Biological Sciences Geneviève A D M Peter R Franklin, MA (BA, Ashok I Handa, MA (MB BS Tommaso Pizzari, MA (BSc Wellcome Trust Career Helleringer (Maîtrise FELLOWS DPhil York) Lond), FRCS Aberd, PhD Shef) Development Fellow ESSEC, JD Columbia, Maîtrise Tutor in Music Fellow by Special Election in Tutor in Zoology Sciences Po, Maîtrise, Richard J Parish, MA, DPhil Professor of Music Medicine James E Thomson, MChem, Doctorat Paris-I Panthéon- (BA Newc) Reader in Surgery Byron W Byrne, MA, DPhil DPhil Sorbonne, Maîtrise Paris-II Tutor in French John Charles Smith, MA Tutor for Graduates (BCom, BEng Western Fellow by Special Election in Panthéon-Assas) Philip Spencer Fellow Tutor in French Linguistics Australia) Chemistry Fellow by Special Election Professor of French President of the Senior James L Bennett, MA (BA Tutor in Engineering Science in Law (Leave H14) Common Room Reading) Tutor for Admissions Andrew J Bunker, MA, DPhil Leverhulme Trust Early Fellow by Special Election Tutor in Physics -

The Church of All Saints Eastchurch in Shepey Robertson

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society ( 374 ) THE OHUBOH OE ALL SAINTS, EASTOHUBCH IN SHEPEY. BY CANON SOOTT ROBERTSON. THE Church of All Saints at Eastchurch has especial interest for antiquaries and students of architecture, because the date of its erection is known. During the ninth year of King Henry VI,* in . November 1431, the chief parishioner, William Cheyne, esquire, of Shirland, obtained the King's license (needful to override the law of mortmain) to give three roods of land, to the Patronsf of East- church Eectory, in order that a new parish church might thereon be built. The soil of Shepey, being London clay, affords no enduring foundation for any edifice. Houses and churches erected on it are in continual peril from the subsidence of the soil; their walls crack in all directions, unless artificial foundations are deeply and solidly laid before any building is commenced. The royal license granted to William Cheyne mentions the fact that the old church at East- church had gone to ruin " by reason of the sudden weakness of the foundation." Consequently, before the Abbot of Boxley began to build a new church, upon the fresh site given by "William Cheyne, he caused deep and solid foundations of chalk to be laid. Wherever a wall was to stand, a wide trench was dug, some feet deep, and it was filled with solid blocks of chalk, brought from the mainland of Kent; thus firm foundations were obtained. Still further to support the walls, diagonal buttresses were constructed at every angle of the building; and three porches (north, south, and west) were erected, with diagonal buttresses at each of their angles; affording much additional support to the walls and to the western tower. -

[Note: This Series of Articles Was Written by Charles Kightly, Illustrated by Anthony Barton and First Published in Military Modelling Magazine

1 [Note: This series of articles was written by Charles Kightly, illustrated by Anthony Barton and first published in Military Modelling Magazine. The series is reproduced here with the kind permission of Charles Kightly and Anthony Barton. Typographical errors have been corrected and comments on the original articles are shown in bold within square brackets.] Important colour notes for modellers, this month considering Parliamentary infantry, by Charles Kightly and Anthony Barton. During the Civil Wars there were no regimental colours as such, each company of an infantry regiment having its own. A full strength regiment, therefore, might have as many as ten, one each for the colonel's company, lieutenant-colonel's company, major's company, first, second, third captain's company etc. All the standards of the regiment were of the same basic colour, with a system of differencing which followed one of three patterns, as follows. In most cases the colonel's colour was a plain standard in the regimental colour (B1), sometimes with 2 a motto (A1). All the rest, however, had in their top left hand corner a canton with a cross of St. George in red on white; lieutenant-colonels' colours bore this canton and no other device. In the system most commonly followed by both sides (pattern 1) the major's colour had a 'flame' or 'stream blazant' emerging from the bottom right hand corner of the St. George (A3), while the first captain's company bore one device, the second captain's two devices, and so on for as many colours as there were companies. -

Puritan Iconoclasm During the English Civil War

Puritan Iconoclasm during the English Civil War Julie Spraggon THE BOYDELL PRESS STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY Volume 6 Puritan Iconoclasm during the English Civil War This work offers a detailed analysis of Puritan iconoclasm in England during the 1640s, looking at the reasons for the resurgence of image- breaking a hundred years after the break with Rome, and the extent of the phenomenon. Initially a reaction to the emphasis on ceremony and the ‘beauty of holiness’ under Archbishop Laud, the attack on ‘innovations’, such as communion rails, images and stained glass windows, developed into a major campaign driven forward by the Long Parliament as part of its religious reformation. Increasingly radical legislation targeted not just ‘new popery’, but pre-Reformation survivals and a wide range of objects (including some which had been acceptable to the Elizabethan and Jacobean Church). The book makes a detailed survey of parliament’s legislation against images, considering the question of how and how far this legislation was enforced generally, with specific case studies looking at the impact of the iconoclastic reformation in London, in the cathedrals and at the universities. Parallel to this official movement was an unofficial one undertaken by Parliamentary soldiers, whose violent destructiveness became notori- ous. The significance of this spontaneous action and the importance of the anti-Catholic and anti-episcopal feelings that it represented are also examined. Dr JULIE SPRAGGON works at the Institute of Historical Research -

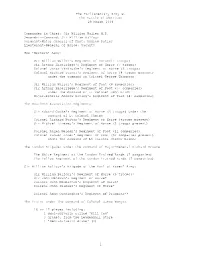

Sir William Waller MP Second-In-Command

The Parliamentary Army at The Battle of Cheriton 29 March 1644 Commander-in-Chief: Sir William Waller M.P. Second-in-Command: Sir William Balfour Sergeant-Major General of Foot: Andrew Potley Lieutenant-General of Horse: vacant? The 'Western' Army: Sir William Waller's Regiment of Horse(11 troops) Sir Arthur Haselrigge's Regiment of Horse (7 troops) Colonel Jonas Vandruske's Regiment of Horse (6 troops) Colonel Richard Turner's Regiment of Horse (4 troops present) under the command of Colonel George Thompson Sir William Waller's Regiment of Foot (8 companies) Sir Arthur Haselrigge's Regiment of Foot (5+ companies) under the command of Lt Colonel John Birch Major-General Andrew Potley's Regiment of Foot (4+ companies) The Southern Association Regiments: Sir Edward Cooke's Regiment of Horse (4 troops) under the command of Lt Colonel Thorpe Colonel Richard Norton's Regiment of Horse (troops present) Sir Michael Livesey's Regiment of Horse (5 troops present) Colonel Ralph Weldon's Regiment of Foot (11 companies) Colonel Samuel Jones' Regiment of Foot (6? companies present) under the command of Lt Colonel Jeremy Baines The London Brigade: under the command of Major-General Richard Browne The White Regiment of the London Trained Bands (7 companies) The Yellow Regiment of the London Trained Bands (7 companies) Sir William Balfour's Brigade of the Earl of Essex' Army: Sir William Balfour's Regiment of Horse (6 troops)* Sir John Meldrum's Regiment of Horse* Colonel John Middleton's Regiment of Horse* Coloenl John Dalbier's Regiment of Horse* Colonel Adam Cunningham's Regiment of Dragoons** The Train: under the command of Colonel James Wemyss 16 or 17 pieces including: 1 demi-culverin called 'Kill Cow' 3 drakes, from the Leadenhall Store 1 'demi-culverin drake' (?) 1 1 saker * These four regiments totalled 22 troops. -

Annual Parochial Church Reports 2019

(Youth Alpha at St John’s) Annual Parochial Church Reports 2019 Charity Number 1155185 2 Annual Vestry & Parochial Church Meeting Tuesday 13th October 2020 · 8.00 pm via Zoom Agenda Annual Vestry Meeting Minutes of Annual Vestry Meeting 2019 p 4 Election of Churchwardens (2) Annual Parochial Church Meeting Apologies Minutes of the Annual Parochial Church Meeting 2019 p 4 Matters arising Electoral Roll – accept new Roll Reports Vicar’s Report p 7 Wardens’ Report p 7 PCC Secretary’s Report p 9 Safeguarding Officer Report p 9 Parish Hub p 10 The Link p 11 Supporting Mission p 11 Deanery Synod Report p 12 Legal Documentation p 14 Trustees Annual Report & Financial Report p 16 Independent Examiner’s Report Questions arising from the Reports Appointment of Treasurer and Secretary Appointment of Safeguarding Officer Election of PCC members, (6 for 3 years) (At Copthorne, for the sake of continuity, if not otherwise elected, the PCC Secretary & Treasurer are co-opted positions.) Election of Deanery Synod Members, (3 for 3 years) Appointment of Sidespersons Appointment of Independent Examiner Any Other Business 3 Copy of the record of the Minutes of The Annual Vestry Meeting held in the church at 10.00am Sunday 24th March 2019 The meeting was conducted by Wim Mauritz (Vicar) in the presence of 62 parishioners. The Minutes of the Vestry Meeting of Sunday 18th March 2018 were unanimously approved. Proposer: John Edwards, Seconder: Sandra Cramp It was unanimously agreed that Section 3 of the Churchwarden’s Measure 2001, shall not apply in relation to this parish until such time as a further meeting of the parishioners may resolve otherwise. -

The Death Warrant of King Charles I

THE DEATH WARRANT OF KING CHARLES I House of Lords Record Office Memorandum No. 66 House of Lords Record Office 1981 “The Mystery of the Death Warrant of Charles I: Some Further Historic Doubts” by A. W. McIntosh, OBE, MA CONTENTS Preface by the Clerk of the Records The Mystery of the Death Warrant of Charles I Transcript of the text of the Warrant Footnotes PREFACE Although constitutional documents as significant as the Bill of Rights are preserved in the care of the House of Lords Record Office, its most famous single document is undoubtedly the Death Warrant of King Charles I. In 1960 the Office published a leaflet containing a photographic reproduction of the Death Warrant, with an historical note, which has proved a best-seller in the HMSO bookshops. The note was based on the ‘received interpretation’ of the history of the document, generally known to historians in Volume 3 of the S. R. Gardiner’s History of the Great Civil War. When the leaflet was issued, the help of the British Museum Research Laboratory was enlisted in order to discover whether modern techniques such as infra-red rays would help to reveal what had been written under various subsequent insertions and corrections. Unfortunately, a seventeenth-century knife had scraped away all too effectively the top surface of the Warrant at places where new text had obviously been inserted. Gardiner’s general account was therefore left unaltered. Recently, however, the Death Warrant has been subjected to a further intensive historical investigation, and this investigation, at the very least, casts some doubts on the original Gardiner doctrine concerning the final stages in the trial of the King. -

The Royalist Rising and Parliamentary Mutinies of 1645 in West Kent

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society THE ROYALIST RISING AND PARLIAMENTARY MUTINIES OF 1645 IN WEST KENT F.D. JOHNS, M.A. The accounts of a royalist rising and the associated parliamentary mutinies in west Kent in April/May 1645 in general histories of the Civil Wars are almost invariably brief and sometimes inaccurate.1 A problem is posed by the apparent unreliability of parts of the principal source material, the Thomason Tracts, a collection of contemporary newspapers, political pamphlets, etc., which were deposited at the British Museum (now the British Library) in 1908. The references to the Thomason Tracts in the footnotes of this paper, E260, E278 and E279, correspond to those of the relevant Tracts as catalogued at the British Library. Another important source is the Calendar of State Papers Domestic Series 1644-45, also at the British Library; references are abbreviated in the footnotes to C.S.P.D. Kent remained throughout the Civil Wars under the firm control of Parliament operating through its County Committee, which was chaired by the dictatorial and unpopular Sir Anthony Weldon of Swanscombe. The Committee's autocratic rule and the punitive taxation which it levied in support of the war were much resented, while the royalist cause continued to command widespread sym- pathy. These factors had been responsible in the summer of 1643 for a rebellion in west Kent led by many of the landed gentry. After the revolt was suppressed its most important leaders were imprisoned, 1 The shortest account, CV. -

![Lord Monson [PDF 70KB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8911/lord-monson-pdf-70kb-6468911.webp)

Lord Monson [PDF 70KB]

MONSON (or Mounson, Munson), SIR WILLIAM, BARON MONSON OF BELLINGUARD, VISCOUNT MUNSON OF CASTLEMAINE (‘Lord Munson’) (born circa 1599, died circa 1672), parliamentary radical, MP 1626, 1628, 1640, 1659 (Reigate), was second son of the noted Admiral Sir William Monson of Kinnersley, Horley, Surrey, and Dorothy, daughter of Richard Wallop of Bugbrooke; he was not son of Sir Thomas Monson (who was really his uncle) as stated in both DNB and Keeler; see Complete Peerage, 1936 ed., correction, IX, 67-9). Monson, by February 1618, was being advanced at Court as a favourite by Lord Suffolk and the Duke of Buckingham, when he was described as a ‘handsome young gentleman’ who had had his face washed every day with posset curd to make the best appearance of his complexion (Nichols, Progress of James I, III, 469). He met with rebuff from the King, but Buckingham saw to it that he was knighted at Theobalds 12 February (not 22 February as wrongly reported in Complete Peerage, op. cit.) 1623 (not 1633 as wrong stated in the DNB), by which time Monson was described dismissively as one ‘who stood once to be a favourite’ (Nichols, op. cit., IV, 804). After this, Monson travelled abroad, presumably on the continent (ibid.). He returned and married 25 October 1625 Margaret, daughter of James Stewart, Earl of Moray, and widow of Admiral Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham (who died 14 December 1624), a woman whose page he had once been (and possibly her lover). This could be described as a fantastic turn of events, as Nottingham had been the elder Monson’s enemy and had imprisoned the younger Monson’s brother John only two and a half years earlier as ‘a most dangerous papist’ (DNB, entry of elder Monson). -

Sir William and Lady Ann Brockman of Beachborough, Newington by Hythe

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 132 2012 SIR WILLIAM AND LADY ANN BROCKMAN OF BEACHBOROUGH, NEWINGTON BY HYTHE. A ROYALIST FAMILY’S EXPERIENCE OF THE CIVIL WAR GILES DRAKE-BROCKMAN A brief note in the 1931 volume of Archaeologia Cantiana describes how a collection of papers belonging to the Brockman family of Beachborough, Newington by Hythe, had come to light and been presented to the British Library.1 The most illustrious member of this family was Sir William Brockman (1595-1654). Sir William had attended the Middle Temple in London (although it is not known if he qualified as a lawyer) and went on to hold a significant position in county society in Kent including being appointed Sheriff in 1642 (but see below). However he is best known for the noble part he played on the Royalist side in the Battle of Maidstone in 1648. In fact, Sir William’s involvement in hostilities against Parliament had begun much earlier, soon after the Civil War broke out. The king had raised his standard at Nottingham and formally declared war against the Parliamentarians on 22 August 1642. The first battle took place at Edgehill in September 1642 with the Royalists gaining victory. However, when the king’s army advanced on London it was met by a large defence force and in mid-November the king withdrew to Oxford. It was at this point that Brockman endeavoured to raise a rebellion against Parliament in Kent. He was sent a commission of array by the king at Oxford while the earl of Thanet was despatched with a regiment through Sussex to support him. -

SPE Spit Uineage

SPE spit vi. SIR WILUAM SPENCEH, -who married Elizabeth, Alice, m. to Granado Pigott, esq. of Abingtoo daughter of Thomas Dee, gent. of Bridgenorth, but Pigott. died without male issue, when the BAHONKTCY passed Sir Brocket d, 3rd July, IOCS, and was $. by his son, to his cousin, (refer to Richard, fourth son of the first n. SIR RICHARU SPENCER, of Offley, who married baronet,) 23rd July, 1P72, Mary, daughter of Sir John Musters, VII. SIR CHARLES SPENCER, who was a minor in knt. of Colwick, Notts, and by her (who married se- 1741, at whose decease the title became EXTINCT. condly, Sir Ralph Radclifie, knt, of Hitchcn,) he left at his decease, in February, 1687-8, a son and succes- Amis—Quarterly, argent and gules, in the second sor, and third quarter, a fret or; over all, a bend sable, m. SIR JOHN SPENCER, of Offley, bapt. 27th Febru- three escallops argent. ary, 1077-8, at whose decease unm- 0th August, 16i)W, the title reverted to his uncle, ir. SIR JOHN SPENCER, of Offley, who d. s. p* 16th November, 1712, aged sixty-seven, when the BARO- SPENCER, OF OFFLEY. NETCY became EXTINCT. The manor of Offley became CREATED 4tb March, 1626.—EXTINCT Sept. 1033. vested in IIIB four sisters, who all d. s. j>. save the eldest, Lady Gore, whose grdndaughter, Anna-Maria Uineage. Penrice, conveyed it to her husband, Sir Thomas Sa- lusbury, SIB RICHARD SPENCER, knt. fourth son of Sir John Spencer, knt. of Althorpe, by Katharine, his wife, Arms—As SPENCER, OF YARNTON. daughter of Sir Thomas Kitson, knt.