Camoenae Hungaricae 7(2010)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dramaturgy of Edmond Rostand. Patricia Ann Elliott Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1968 The Dramaturgy of Edmond Rostand. Patricia Ann Elliott Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Elliott, Patricia Ann, "The Dramaturgy of Edmond Rostand." (1968). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1483. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1483 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microiilmed exactly as received 69-4466 ELLIOTT, Patricia Ann, 1937- THE DRAMATURGY OF EDMOND ROSTAND. [Portions of Text in French]. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1968 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE DRAMATURGY OF EDMOND ROSTAND A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy m The Department of Foreign Languages by Patricia Ann Elliott B.A., Catawba College, 1958 M.A., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1962 August, 1968 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my deep personal appreciation to Professor Elliott Dow Healy for his inspiration to me and guidance of my studies at Louisiana State University, and particularly for his direction of this dissertation. I am especially grateful to my parents for their encouragement throughout my studies. -

1 Education Resource Pack Adapted by Deborah Mcandrew from The

Northern Broadsides Education Resource Pack Adapted by Deborah McAndrew From the original play Cyrano de Bergerac by Edmond Rostand Directed by Conrad Nelson Designer - Lis Evans Lighting Designer - Daniella Beattie Musical Director – Rebekah Hughes Presented in partnership with The New Vic Theatre, Newcastle-u-Lyme 1 About this pack We hope that teachers and students will enjoy our production and use this learning resource pack. It may be used in advance of seeing the performance – to prepare and inform students about the play; and afterwards – to respond to the play and explore in more depth. Teachers may select, from the broad range of material, which is most suitable for their students. The first section of this document is a detailed companion to our production: plot synopsis, who’s who in the play, and interviews with cast and creatives. It reveals the ways in which our company met with the many challenges of bringing CYRANO to the stage. The second section examines the background to the play. The original work by Edmond Rostand, and the real life Cyrano and his world; and the poetic content and context of the play. At the end of the second section are exercises and suggestions for study in the subjects of History, English and Drama. CYRANO by Deborah McAndrew, is published by Methuen and available to purchase from http://www.northern- broadsides.co.uk 2 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 4 SECTION ONE Our play Characters 5 Plot synopsis Production Meet the team: In rehearsal – o Nose to nose with Christian Edwards o Eye to Eye with Francesca Mills A Stitch In Time – with the New Vic ‘Wardrobe’ Let there be light – with Daniella Beattie SECTION TWO Backstory Edmond Rostand The Real Cyrano Poet’s corner Verse and Cyrano SECTION THREE STUDY History, Literacy, Drama Credits and Links 40 3 INTRODUCTION The play CYRANO is a new English language adaptation of a French classic play by Edmond Rostand entitled Cyrano de Bergerac. -

1989 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Illinois Shakespeare Festival Fine Arts Summer 1989 1989 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/isf Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation School of Theatre and Dance, "1989 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program" (1989). Illinois Shakespeare Festival. 8. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/isf/8 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Fine Arts at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illinois Shakespeare Festival by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The 1989 Illinois Shakespeare I Illinois State University Illinois Shakespeare Festival Dear friends and patrons, Welcome to the twelfth annual Illinois Shakespeare Festival. In honor of his great contributions to the Festival, we dedicate this season to the memory of Douglas Harris, our friend, colleague and teacher. Douglas died in a plane crash in the fall of 1988 after having directed an immensely successful production of Richard III last summer. His contributions and inspiration will be missed by many of us, staff and audience alike. We look forward to the opportunity to share this season's wonderful plays, including our first non-Shakespeare play. For 1989 and 1990 we intend to experiment with performing classical Illinois State University plays in addition to Shakespeare that are suited to our acting company and to our theatre space. Office of the President We are excited about the experiment and will STATE OF ILLINOIS look forward to your responses. -

Xerox University Microfilms

SKEPTICISM AND DOCTRINE IN THE WORKS OF CYRANO DE BERGERAC (1619--1655) Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Johnson, Charles Richard, 1927- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 06:30:47 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288336 INFORMATION TC USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. -

Cyrano De Bergerac

Cyrano de Bergerac Summer Reading Guide - English 10 Howdy, sophomores! Cyrano de Bergerac is a delightful French play by Edmond Rostand about a swashbuckling hero with a very large nose. It is one of my favorites! Read this entire guide before starting the play. The beginning can be tough to get through because there are many confusing names and characters, but stick with it and you won’t be disappointed! On the first day of class, there will be a Reading Quiz to test your knowledge of this guide and your comprehension of the play’s main events and characters. If you are in the honors section, you will also write a Timed Writing essay the first week of school. After school starts, we will analyze the play in class through discussions and various writing assignments. We will conclude the unit by watching a French film adaptation and comparing it to the play. By the way, my class is a No Spoiler Zone. This means that you may NOT spoil significant plot events to classmates who have not yet read the book. If you have questions about the reading this summer, please email me at [email protected]. I’ll see you in the fall! - Mrs. Lee 1 Introduction Cyrano de Bergerac is a 5-act play by French dramatist and poet Edmond Rostand (1868-1918). Our class version was translated into English by Gertrude Hall. Since its 1897 Paris debut, the play has enjoyed numerous productions in multiple countries. Cultural & Historical Background By the end of the 1800s, industrialization was taking place in most of Europe, including France, and with it came a more scientific way of looking at things. -

Rina Mahoney

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Rina Mahoney Talent Representation Telephone Elizabeth Fieldhouse +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected] Address Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Theatre Title Role Director Theatre/Producer HAMLET Gertrude Damian Cruden Shakespeares Rose Theatre, York TWELFTH NIGHT Maria Joyce Branagh Shakespeares Rose Theatre, York DEATH OF A SALESMAN The Woman Sarah Frankcom Royal Exchange Theatre Shakespeare's Rose MACBETH Lady Macduff/Young Siward Damian Cruden Theatre/Lunchbox Productions Shakespeare's Rose A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM Peter Quince Juliet Forster Theatre/Lunchbox Productions THE PETAL AND THE ORCHID Kathryn Cat Robey Underexposed Theatre THE SECRET GARDEN Ayah/Dr Bres Liz Stevenson Theatre by the Lake ROMEO AND JULIET Nurse Justin Audibert RSC (BBC Live) MACBETH Witch 2 Justin Audibert RSC (BBC Live) ZILLA Rumani Joyce Branagh The Gap Project Duke of Venice/Portia's THE MERCHANT OF VENICE Polly Findlay RSC Servant OTHELLO Ensemble/Emillia Understudy Iqbal Khan RSC Birmingham Repertory FADES, BRAIDS AND KEEPING IT REAL Eva Antionette Lecester Theatre/Sharon Foster Productions CALCUTTA KOSHER Maki Janet Steel Arcola/Kali ARE WE NEARLY THERE YET? Various Matthew Lloyd Wilton's Music Hall FLINT STREET NATIVITY The Angel Matthew Lloyd Hull Truck Theatre MATCH Jasmin Jenny Stephens Hearth UNWRAPPED FESTIVAL Various Gwenda Hughes Birmingham Repertory Theatre HAPPY NOW Bea Matthew Lloyd Hull Truck Theatre Company MIRIAM ON 34TH STREET Kathy Jenny Stephens Something & Nothing -

Musical Theater Sheet

FACT MUSICAL THEATER SHEET Established by Congress in 1965, the National Endowment for the Arts is the independent federal agency whose funding and support gives Americans the opportunity to participate in the arts, exercise their imaginations, and develop their creative capacities. Through partnerships with state arts agencies, local leaders, other federal agencies, and the philanthropic sector, the Arts Endowment supports arts learning, affirms and celebrates America’s rich and diverse cultural heritage, and extends its work to promote equal access to the arts in every community across America. The National Endowment for the Arts is the only funder, public or private, to support the arts in all 50 states, U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia. The agency awards more than $120 million annually with each grant dollar matched by up to nine dollars from other funding sources. Economic Impact of the Arts The arts generate more money to local and state economies than several other industries. According to data released by the National Endowment for the Arts and the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the arts and cultural industries contributed $804.2 billion to the U.S. economy in 2016, more than agriculture or transportation, and employed 5 million Americans. FUNDING THROUGH THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS MUSICAL THEATER PROGRAM: Fiscal Year 2018 marked the return of musical theater as its own discipline for grant award purposes. From 2014-2017, grants for musical theater were included in the theater discipline and prior to 1997, were awarded with opera as the opera/musical theater discipline. The numbers below, reflect musical theater grants awarded only when there was a distinct musical theater program. -

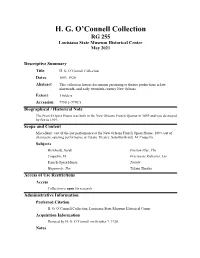

H. G. O'connell Collection

H. G. O’Connell Collection RG 255 Louisiana State Museum Historical Center May 2021 Descriptive Summary Title: H. G. O’Connell Collection Dates: 1893–1920 Abstract: This collection houses documents pertaining to theater productions in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century New Orleans. Extent: 5 folders Accession: 7790.1–7790.5 Biographical / Historical Note The French Opera House was built in the New Orleans French Quarter in 1859 and was destroyed by fire in 1919. Scope and Content Miscellany: cast of the last performance at the New Orleans French Opera House; 1893 cast of characters; opening performance at Tulane Theatre; Sara Bernhardt, M. Coquelin. Subjects Bernhardt, Sarah Passion Play, The Coquelin, M. Precieuses Ridicules, Les French Opera House Tartufe Huguenots, The Tulane Theatre Access of Use Restrictions Access Collection is open for research. Administrative Information Preferred Citation H. G. O’Connell Collection, Louisiana State Museum Historical Center Acquisition Information Donated by H. G. O’Connell on October 7, 1920. Notes Documents are in poor condition, and some portions are in French. List of Content Folder Date Item Description Newspaper clipping from November 30, 1893. Cast list of production of Tartufe at the French Opera House. Headlining actor: Folder 1 1893 November 30 M. Coquelin. Theater program from week of March 4, 1901 at Tulane Theatre. Includes cast list of productions of La Tosca, Cyrano de Bergerac, Phedre, Les Precieuses Ridicules, and La Dame Aux Camelias. Folder 2 1901 March 4 Headlining actors: Sarah Bernhardt and M.Coquelin. Theater program from a production of The Passion Play on Sunday April 16, 1916 at the French Opera House. -

November 2017 • 50Freeevents

NOVEMBER 2017 • 50 FREE EVENTS BY DATE Wednesdays, Nov. 1-Dec. 20, 10-11:30am. Encinitas Comm. Ctr., 1140 Oak Crest Park Dr. $142.50, $152.50 Musical Spanish Preschool Class. Ages 2½-5 years. Musical Spanish is a fun, dynamic class that includes singing, dancing, books, and games. The instructor is a native speaker who holds an Early Childhood Education certificate. Parent participation is required. Info: www.EncinitasParksandRec.com 760-943-2260 Wednesday, November 1, 12:00-12:45pm. Encinitas Library, 540 Cornish Drive. Free Wednesdays@Noon: Virginia Sublett, soprano, Gabriel Arregui, piano. Virginia has appeared as principal artist with opera companies throughout the United States and France, including New York City Opera, Los Angeles Opera, and San Diego Opera. Gabriel has appeared for 22 seasons as soloist and in chamber ensembles with the Baroque Music Festival of Corona del Mar. They will perform works by Copland, Poulenc, Ives and Guastavino. (Cultural Arts Division) Info: www.Encinitasca.gov/WedNoon 760-633-2746. Wed. & Sun. Nov. 1-29. Call for times. Encinitas Comm. Center, 1140 Oak Crest Park Drive. $27.50, $37.50 Karate. Ages 8 years and older. Designed to teach the art, discipline, and traditions of classic Japanese Karate. Students will learn fundamentals for the purpose of developing character, respect, conditioning, and self-protection. Info: www.EncinitasParksandRec.com 760-943-2260. Every Wednesday, 3-4pm. EOS Fitness, 780 Garden View Court. Free to cancer patients and survivors Zumba: Gentle Dance Fitness Class for Cancer Recovery. Research shows that movement to music provides a wide range of benefits: it reduces physical and mental fatigue, increases blood flow, aids lymphatic system and boosts immunity. -

{PDF EPUB} Doctor Who the Mind Robber by Peter Ling Doctor Who: the Mind Robber by Peter Ling

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who The Mind Robber by Peter Ling Doctor Who: The Mind Robber by Peter Ling. After an emergency dematerialisation, the TARDIS lands in a weird white void. Jamie and Zoe are tempted out of the time machine into a trap, while the Doctor fends off a psychic assault. In a desperate bid to escape, the Doctor tries to pilot the TARDIS somewhere else, only for the time machine to break apart. Suddenly, the three companions find themselves in a surreal world where imagination has become reality, populated by characters out of folklore and literature. They must navigate a series of riddles and deadly encounters to reach the mysterious Master of the realm. But what designs does he have for the Doctor? Production. Just before joining Doctor Who , story editor Derrick Sherwin and his assistant, Terrance Dicks, had written for the soap opera Crossroads , co- created by Peter Ling. The three men regularly travelled together by train and, one day in late 1967, Ling remarked on the way that soap opera characters could be treated like real people by some fans. Sherwin suggested that this might form a suitable basis for a Doctor Who story and, shortly thereafter, Ling put together a proposal called “The Fact Of Fiction”. On the basis of this submission, on December 20th, Ling was commissioned to write an outline for a six-part story, now entitled “Man Power”. Early in the new year, the serial's length was truncated to four episodes; the title also underwent a slight change to “Manpower”, although this would be applied inconsistently. -

Green Meadow Waldorf School Outside Reading List 1996-1997

GREEN MEADOW WALDORF SCHOOL OUTSIDE READING LIST GRADES 9 and 10 ❖ 2019-2020 REMINDERS: 1) Read as many plays as you wish, but choose only one for a book report. 2) If you choose to write on a work of literature not on this list, you must check with your English teacher first to receive approval. 3) Passing off a previously written book report, yours or someone else’s, will be considered a serious violation of academic ethics and will be dealt with sternly. ❖ FICTION AND BIOGRAPHY ❖ Winesburg, Ohio Anderson Collection of short stories depicting a small mid-western town early in the century. Things Fall Apart Achebe A modern Nigerian makes his way between timeless tradition and modern change. A Man of the People Achebe A young man experiences the inside track of the “People’s Leader” in an African country. A Long Way Gone (B) Beah Ismael Beah tells of his experience as a boy soldier, picked up at the age of 13 by the government army of Sierra Leone. The Exonerated Blank & The authors combine their interviews with people exonerated from (Play) Jensen death row with their own memoirs of how they explored these people’s stories to create a play from the material. Caleb’s Crossing Brooks A fine, well-textured story of early inhabitants of Martha’s Vineyard, both white and Wampanoag, as the two cultures influence each other. Vividly set in the 1660s. The Tracker (B) Brown An autobiographical account of a boy who learns how to track animals and live Indian-wise and self-sufficient in the wilderness. -

Voyages Towards Utopia: Mapping Utopian Spaces in Early-Modern French Prose

Voyages Towards Utopia: Mapping Utopian Spaces in Early-Modern French Prose By Bonnie Griffin Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in French Literature March 31st, 2020 Nashville, TN Approved: Holly Tucker, PhD Lynn Ramey, PhD Paul Miller, PhD Katherine Crawford, PhD DEDICATIONS To my incredibly loving and patient wife, my supportive family, encouraging adviser, and dear friends: thank you for everything—from entertaining my excited ramblings about French utopia, looking at strange engravings of monsters on maps with me, and believing in my project. You encouraged me to keep working and watched me create my life’s most significant work yet. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my adviser and mentor Holly Tucker, who provided me with the encouragement, helpful feedback, expert time-management advice, and support I needed to get to this point. I am also tremendously grateful to my committee members Lynn Ramey, Paul Miller, and Katie Crawford. I am indebted to the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities, for granting me the necessary space, time, and resources to prioritize my dissertation. I wish to thank the Department of French and Italian, for taking a chance on a young undergrad. I also wish to acknowledge the Vanderbilt University Special Collections team of archivists and librarians, for facilitating my access to the texts that would substantially inform and inspire my studies, as well as the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. I also wish to thank Laura Dossett and Nathalie Debrauwere-Miller for helping me through the necessary processes involved in preparing for my defense.