EU Withdrawal: Transitional Provisions and Dispute Resolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

Stalemate by Design? How Binary Voting Caused the Brexit Impasse of 2019

Munich Social Science Review, New Series, vol. 3 (2020) Stalemate by Design? How Binary Voting Caused the Brexit Impasse of 2019 G. M. Peter Swann Nottingham University Business School, Nottingham NG8 1BB, United Kingdom, [email protected] Abstract: Between January and April, 2019, the UK parliament voted on the Prime Minister’s proposed Brexit deal, and also held a series of indicative votes on eight other Brexit options. There was no majority support in any of the votes for the Prime Minister’s deal, nor indeed for any of the other options. This outcome led to a prolonged period of political stalemate, which many people considered to be the fault of the Prime Minister, and her resignation became inevitable. Controversially, perhaps, I shall argue that the fault did not lie with the Prime Minster, but with Parliament’s stubborn insistence on using its default binary approach to voting. The outcome could have been quite different if Parliament had been willing to embrace the most modest of innovations: a voting system such as the single transferable vote, or multi-round exhaustive votes, which would be guaranteed to produce a ‘winner’. Keywords: Brexit, Parliament, Binary Votes, Indicative Votes, Single Transferable Vote, Exhaustive Votes 1. Introduction This paper considers the impasse in the Brexit process that developed from the start of 2019. I argue that an important factor in the emergence of this impasse was the use of binary voting – the default method of voting in the Westminster Parliament. I shall argue that alternative voting processes would have had a much greater chance of success. -

Meeting As03:0708

AS MEETING AS02m 14:15 DATE 04.06.14 South Somerset District Council Draft Minutes of a meeting of the Area South Committee held in the Council Chamber, Brympton Way, Yeovil, on Wednesday 4th June 2014. (2.00pm – 4.05pm) Present: Members: Peter Gubbins (In the Chair) Cathy Bakewell Tony Lock Tim Carroll Graham Oakes Tony Fife Wes Read Marcus Fysh David Recardo Jon Gleeson John Richardson Dave Greene Gina Seaton Andy Kendall Peter Seib Pauline Lock Officers: Jo Boucher Democratic Services Officer Kim Close Area Development Manager, South Adrian Noon Area Leads North/East Simon Fox Area Lead South Michael Jones Locum Planning Solicitor Neil Waddleton Section 106 Monitoring Officer 4. Minutes of meeting held on 7th May 2014 and 15th May 2014 (Agenda Item 1) The minutes of the Area South meeting held on 7th May 2014 and 15th May 2014 copies of which had been circulated, were agreed as a correct record and signed by the Chairman. 5. Apologies for Absence (Agenda Item 2) Apologies for absence were received from Councillors John Vincent Chainey, Nigel Gage and Ian Martin. 6. Declarations of Interest (Agenda Item 3) Cllr Peter Gubbins declared a personal and prejudicial interest in Agenda Item 7- Planning Application 14/01266/OUT as his son lives in close proximity of the proposed site. He would leave the meeting during consideration of that item. AS02M 1 04.06.14 AS 7. Public Question Time (Agenda Item 4) There were no questions from members of the public. 8. Chairman’s Announcements (Agenda Item 5) There were no Chairman’s announcements. -

Stephen Kinnock MP Aberav

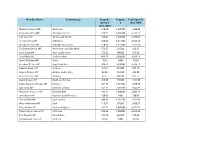

Member Name Constituency Bespoke Postage Total Spend £ Spend £ £ (Incl. VAT) (Incl. VAT) Stephen Kinnock MP Aberavon 318.43 1,220.00 1,538.43 Kirsty Blackman MP Aberdeen North 328.11 6,405.00 6,733.11 Neil Gray MP Airdrie and Shotts 436.97 1,670.00 2,106.97 Leo Docherty MP Aldershot 348.25 3,214.50 3,562.75 Wendy Morton MP Aldridge-Brownhills 220.33 1,535.00 1,755.33 Sir Graham Brady MP Altrincham and Sale West 173.37 225.00 398.37 Mark Tami MP Alyn and Deeside 176.28 700.00 876.28 Nigel Mills MP Amber Valley 489.19 3,050.00 3,539.19 Hywel Williams MP Arfon 18.84 0.00 18.84 Brendan O'Hara MP Argyll and Bute 834.12 5,930.00 6,764.12 Damian Green MP Ashford 32.18 525.00 557.18 Angela Rayner MP Ashton-under-Lyne 82.38 152.50 234.88 Victoria Prentis MP Banbury 67.17 805.00 872.17 David Duguid MP Banff and Buchan 279.65 915.00 1,194.65 Dame Margaret Hodge MP Barking 251.79 1,677.50 1,929.29 Dan Jarvis MP Barnsley Central 542.31 7,102.50 7,644.81 Stephanie Peacock MP Barnsley East 132.14 1,900.00 2,032.14 John Baron MP Basildon and Billericay 130.03 0.00 130.03 Maria Miller MP Basingstoke 209.83 1,187.50 1,397.33 Wera Hobhouse MP Bath 113.57 976.00 1,089.57 Tracy Brabin MP Batley and Spen 262.72 3,050.00 3,312.72 Marsha De Cordova MP Battersea 763.95 7,850.00 8,613.95 Bob Stewart MP Beckenham 157.19 562.50 719.69 Mohammad Yasin MP Bedford 43.34 0.00 43.34 Gavin Robinson MP Belfast East 0.00 0.00 0.00 Paul Maskey MP Belfast West 0.00 0.00 0.00 Neil Coyle MP Bermondsey and Old Southwark 1,114.18 7,622.50 8,736.68 John Lamont MP Berwickshire Roxburgh -

(A) Ex-Officio Members

Ex-Officio Members of Court (A) EX-OFFICIO MEMBERS (i) The Chancellor His Royal Highness The Earl of Wessex (ii) The Pro-Chancellors Sir Julian Horn-Smith Mr Peter Troughton Mr Roger Whorrod (iii) The Vice-Chancellor Professor Dame Glynis Breakwell (iv) The Treasurer Mr John Preston (v) The Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Pro-Vice-Chancellors Professor Bernie Morley, Deputy Vice-Chancellor & Provost Professor Jeremy Bradshaw, Pro-Vice-Chancellor (International & Doctoral) Professor Jonathan Knight, Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Research) Professor Peter Lambert, Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Learning & Teaching) (vi) The Heads of Schools Professor Veronica Hope Hailey, Dean and Head of the School of Management Professor Nick Brook, Dean of the Faculty of Science Professor David Galbreath, Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Professor Gary Hawley, Dean of the Faculty of Engineering and Design (vii) The Chair of the Academic Assembly Dr Aki Salo (viii) The holders of such offices in the University not exceeding five in all as may from time to time be prescribed by the Ordinances Mr Mark Humphriss, University Secretary Ms Kate Robinson, University Librarian Mr Martin Williams, Director of Finance Ex-Officio Members of Court Mr Martyn Whalley, Director of Estates (ix) The President of the Students' Union and such other officers of the Students' Union as may from time to time be prescribed in the Ordinances Mr Ben Davies, Students' Union President Ms Chloe Page, Education Officer Ms Kimberley Pickett, Activities Officer Mr Will Galloway, Sports -

2018 MARCH EYE.P65

MARCH 2018 Our Local Library Under Threat Peter Little CBE 1943 - 2018 Somerset County Council has embarked on a consultation exercise in regard to the Library Service. Our local library at South Petherton is earmarked for closure. “In summary, under the proposals,15 of Somerset’s 34 libraries would be seeking community involvement to remain open.” Peter, who lived in Frog Street, died sudenly at the end of January from Full details are at complications following a medical www.somerset.gov.uk/ procedure. Peter played an active librariesconsultation role in village life since moving here For any questions about the proposals, please email with Penny in 2005, including as [email protected] chairman of Lopen Parish Council 2007 - 2011 when he fought valiantly for Lopen’s interests. Peter enjoyed a distinguished and varied career in public service both in the UK and overseas. NEWS from SLOW SLOW is the village NEWS from SLOW campaign to The shocking reality of stop speeding speeding through our village through Lopen Over six days at the end of January this year 8,239 vehicles passed through Lopen of which some 4 out of 10 were driven at or below the 30mph speed limit. That leaves the remaining 6 out of 10 being driven illegally at speeds in excess of the speed limit. Over half of these were recorded at speeds between 40-50mph. No fewer than 53 drivers were logged at over 60mph and three individuals, believe it or not, at more than 70mph. This detail was recorded on a Speed Indicator Device (SID) which, on temporary loan, was positioned on the grass verge on the Holloway - Merriott Road by a member of Lopen’s SLoW campaign. -

Urgent Open Letter to Jesse Norman Mp on the Loan Charge

URGENT OPEN LETTER TO JESSE NORMAN MP ON THE LOAN CHARGE Dear Minister, We are writing an urgent letter to you in your new position as the Financial Secretary to the Treasury. On the 11th April at the conclusion of the Loan Charge Debate the House voted in favour of the motion. The Will of the House is clearly for an immediate suspension of the Loan Charge and an independent review of this legislation. Many Conservative MPs have criticised the Loan Charge as well as MPs from other parties. As you will be aware, there have been suicides of people affected by the Loan Charge. With the huge anxiety thousands of people are facing, we believe that a pause and a review is vital and the right and responsible thing to do. You must take notice of the huge weight of concern amongst MPs, including many in your own party. It was clear in the debate on the 4th and the 11th April, that the Loan Charge in its current form is not supported by a majority of MPs. We urge you, as the Rt Hon Cheryl Gillan MP said, to listen to and act upon the Will of the House. It is clear from their debate on 29th April that the House of Lords takes the same view. We urge you to announce a 6-month delay today to give peace of mind to thousands of people and their families and to allow for a proper review. Ross Thomson MP John Woodcock MP Rt Hon Sir Edward Davey MP Jonathan Edwards MP Ruth Cadbury MP Tulip Siddiq MP Baroness Kramer Nigel Evans MP Richard Harrington MP Rt Hon Sir Vince Cable MP Philip Davies MP Lady Sylvia Hermon MP Catherine West MP Rt Hon Dame Caroline -

Daily Report Tuesday, 15 December 2020 CONTENTS

Daily Report Tuesday, 15 December 2020 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 15 December 2020 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:46 P.M., 15 December 2020). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 7 Travel: Quarantine 15 ATTORNEY GENERAL 7 Utilities: Ownership 16 Food: Advertising 7 CABINET OFFICE 16 Immigration: Prosecutions 8 Consumer Goods: Safety 16 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Government Departments: INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 9 Databases 16 Arcadia Group: Insolvency 9 Honours 16 Carbon Emissions 9 Prime Minister: Electric Climate Change 10 Vehicles 17 Coronavirus Job Retention DEFENCE 17 Scheme 10 Afghanistan and Iraq: Reserve Coronavirus: Disease Control 11 Forces 17 Employment: Coronavirus 11 Armed Forces: Coronavirus 18 Energy: Housing 11 Armed Forces: Finance 18 Facebook: Competition Law 12 Army: Training 19 Hospitality Industry: Autonomous Weapons 20 Coronavirus 13 Clyde Naval Base 20 Hydrogen: Garages and Petrol Defence: Procurement 21 Stations 13 Mali: Armed Forces 21 Public Houses: Wakefield 13 Military Aid 23 Regional Planning and Military Aircraft 23 Development 14 Ministry of Defence: Renewable Energy: Urban Recruitment 23 Areas 14 Reserve Forces 24 Sanitary Protection: Safety 14 Reserve Forces: Pay 25 Shops: Coronavirus 15 Reserve Forces: Training 25 Russia: Navy 26 Cattle Tracing System 39 Saudi Arabia: Military Aid 26 Cattle: Pneumonia 39 Unmanned -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 687 18 January 2021 No. 161 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 18 January 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 601 18 JANUARY 2021 602 David Linden [V]: Under the Horizon 2020 programme, House of Commons the UK consistently received more money out than it put in. Under the terms of this agreement, the UK is set to receive no more than it contributes. While universities Monday 18 January 2021 in Scotland were relieved to see a commitment to Horizon Europe in the joint agreement, what additional funding The House met at half-past Two o’clock will the Secretary of State make available to ensure that our overall level of research funding is maintained? PRAYERS Gavin Williamson: As the hon. Gentleman will be aware, the Government have been very clear in our [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] commitment to research. The Prime Minister has stated Virtual participation in proceedings commenced time and time again that our investment in research is (Orders, 4 June and 30 December 2020). absolutely there, ensuring that we deliver Britain as a [NB: [V] denotes a Member participating virtually.] global scientific superpower. That is why more money has been going into research, and universities will continue to play an incredibly important role in that, but as he Oral Answers to Questions will be aware, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy manages the research element that goes into the funding of universities. -

Brexit Timeline

BREXIT TIMELINE BREXIT TIMELINE 1 BREXIT TIMELINE 6 December 2005 David Cameron becomes Conservative leader David Cameron wins the leadership of the Conservative Party. In the campaign, he promises to take the party out of the European People’s Party (EPP) grouping in the European Parliament 1 October 2006 Cameron first conference speech In his first conference speech, David Cameron implores his party to stop ‘banging on about Europe’ 4 June 2009 European Parliament elections The 2009 European Parliament elections see the UK Independence Party (UKIP) finished second in a major election for the first time in its history. 22 June 2009 Conservative Party form new grouping Conservative MEPs form part of a new group in the European Conservatives and Reformists group (ECR), as the party formally leaves the EPP. 20 May 2010 Coalition agrees to status quo on Europe The Coalition Agreement is published, which states that ‘Britain should play a leading role in an enlarged European Union, but that no further powers should be transferred to Brussels without a referendum.’ 5 May 2011 Alternative Vote referendum The UK holds a referendum on electoral reform and a move to the Alternative Vote. The No to AV campaign – led by many figures who would go on to be part of Vote Leave – wins decisively by a margin of 68% to 32%. 9 December 2011 David Cameron vetoes The Prime Minister vetoes treaty change designed to help manage the Eurozone crisis, arguing it is not in the UK’s interest – particularly in restrictions the changes might place on financial services. 23 January 2013 The Bloomberg Speech In a speech at Bloomberg’s offices in central London, David Cameron sets out his views on the future of the EU and the need for reform and a new UK-EU settlement. -

Open PDF 226KB

European Scrutiny Committee Oral evidence: The institutional framework of the UK/EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement, HC 450 Monday 12 July 2021 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on Monday 12 July 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Sir William Cash (Chair); Jon Cruddas; Allan Dorans; Richard Drax; Margaret Ferrier; Mr Marcus Fysh; Mrs Andrea Jenkyns; Mr David Jones; Craig Mackinlay; Anne Marie Morris. Questions 1 - 44 Witnesses I: Christophe Bondy, Partner, Steptoe & Johnson LLP; Professor David Collins, Professor of International Economic Law, City, University of London; Dr Lorand Bartels, Lecturer in International Law, University of Cambridge, and Counsel, Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP; and Martin Howe QC, Barrister, 8 New Square Chambers. Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Christophe Bondy, Professor Collins, Dr Bartels and Martin Howe. Q1 Chair: On behalf of the Committee, I welcome you all and thank you for appearing to give evidence this afternoon. As you will be aware, as part of our recently initiated inquiry, we are investigating the governance structure of the UK-EU trade and co-operation agreement, otherwise known as the TCA. Today, with your considerable experience and knowledge, we would like to achieve a better understanding of, first, the bodies that the TCA establishes—what they are and what they can do; secondly, the transparency requirements of the committees that the TCA establishes; thirdly, the relevant dispute resolution mechanisms and remedies for breaches of the agreement; and, fourthly, the development of the TCA in terms of how it will interact with future UK-EU, and UK-EU member state, supplementing agreements.