Passing As Modernism 385

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travel Papers in American Literature

ROAD SHOW Travel Papers in American Literature This exhibition celebrates the American love of travel and adventure in both literary works and the real-life journeys that have inspired our most beloved travel narratives. Exploring American literary archives as well as printed and published works, Road Show reveals how travel is recorded, marked, and documented in Beinecke Library’s American collections. Passports and visas, postcards and letters, travel guides and lan- guage lessons—these and other archival documents attest to the physical, emotional, and intellectual experiences of moving through unfamiliar places, encountering new landscapes and people, and exploring different ways of life and world views. Literary manuscripts, travelers’ notebooks, and recorded reminiscences allow us to consider and explore travel’s capacity for activating the imagination and igniting creativity. Artworks, photographs, and published books provide opportunities to consider the many ways artists and writers transform their own activities and human interactions on the road into works of art that both document and generate an aesthetic experience of journeying. 1-2 Luggage tag, 1934, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers 3 Langston Hughes, Mexico, undated, Langston Hughes Papers 4 Shipboard photograph of Margaret Anderson, Louise Davidson, Madame Georgette LeBlanc, undated, Elizabeth Jenks Clark Collection of Margaret Anderson 5-6 Langston Hughes, Some Travels of Langston Hughes world map, 1924-60, Langston Hughes Papers 7 Ezra Pound, Letter to Viola Baxter Jordan with map, 1949, Viola Baxter Jordan Papers 8 Kathryn Hulme, How’s the Road? San Francisco: Privately Printed [Jonck & Seeger], 1928 9 Baedeker Handbooks for Greece, Belgium and Holland, Paris, Berlin, Great Britain, various dates 10 H. -

Macleod, Kirsten, Ed. 2018. Carl Van Vechten, the Blind Bow- Boy

144 | Textual Cultures 12.2 (2019) MacLeod, Kirsten, ed. 2018. Carl Van Vechten, The Blind Bow- Boy. Cambridge, UK: Modern Humanities Research Association. Pp. xxviii + 152. ISBN 9781781882900, Paper $17.99. Carl Van Vechten’s The Blind Bow-Boy (1923) is a book about pleasure — about the kinds of pleasure taken by 1920s dandies in literature, per- formance, perfumes, fashion, cocktails, Coney Island, and car rides; about sexual pleasures and the pleasure of solitude; about fads and the short shelf- life of certain kinds of pleasure; about whether one can learn from things that are pleasurable and whether one can learn to take pleasure. It is a modernist novel written in a Decadent register. The cataloguing of inte- riors frequently stands in for character development. The reader comes to understand who people are according to the kinds of tableware with which they surround themselves or in which they are able to find joy. The text speaks in commodity code, mixing the high and the low, mass and high culture, addressing itself to a readership who knows their French literature and avant-garde art and music as well as their fashion houses, perfumiers, and parlor songs. It expects from its audience a deep awareness of literary history as well as an up-to-date savvy concerning bestsellers and modern- ist trends. One is meant to feel whipped about by the whirlwind of things one might enjoy in 1920s New York by visiting certain neighborhoods, booksellers, and beautifully outfitted apartments. In conveying so much detail about the richness of modern pleasure, however, Van Vechten con- structed a novel that demands a certain kind of cultural literacy. -

James Cummins Bookseller

JAMES CUMMINS BOOKSELLER A Selection of Books to Be Exhibited at the 51st ANNUAL NEW YORK ANTIQUARIAN BOOK FAIR BOOTH E5 APRIL 8-10 Friday noon - 8pm Saturday noon - 7pm Sunday noon - 5pm The Park Avenue Armory 643 Park Avenue, at 67th Street, New York City James Cummins Bookseller • 699 Madison Ave, New York, 10065 • (212) 688-6441 • [email protected] James Cummins Bookseller — Both E5 2011 New York Antiquarian Book Fair 1. (ALBEE, Edward) Van Vechten, Carl. Portrait photograph of Edward Albee. Half-length, seated, in semi- profile. Gelatin silver print. 35 x 23 cm. (approx 14 x 8-3/4 inches), New York: April 18, 1961. Published in Portraits: the Photographs of Carl Van Vechten (1978). Fine. Verso docketed with holograph notations in pencil giving the name of the sitter, date of the photograph, and the the Van Vechten’s reference to negative and print (“VII SS:19”). $2,000 Inscribed by Co-Writer Marshall Brickman 2. [ALLEN, Woody and Marshall Brickman]. Untitled Film Script [Annie Hall]. 120 ff., + 4 ff. appendices. 4to, n.p: [April 15, 1976]. Mechanically reproduced facsimile of Marshall Brickman’s early numbered (#13) screenplay with numerous blue revision pages. Bound with fasteners. Fine. $1,250 With a lengthy INSCRIPTION by co-writer Marshall Brickman. This early version of the script differs considerably from the final shooting version. It is full of asides, flashbacks, gags, and set pieces. It resembles Allen’s earlier screwball comedies and doesn’t fully reflect his turn to a more “serious” kind of filmmaking. Sold to benefit the Writers of America East Foundation and its programs Inscribed by Co-Writer Marshall Brickman 3. -

Advanced September 2005.Indd

Contact: Norman Keyes, Jr. Edgar B. Herwick III Director of Media Relations Press Relations Coordinator 215.684.7862 215.684.7365 [email protected] [email protected] SCHEDULE OF NEW & UPCOMING EXHIBITIONS THROUGH SPRING 2007 This Schedule is updated quarterly. For the latest information please call the Marketing and Public Relations Department NEW AND UPCOMING EXHIBITIONS Looking at Atget September 10–November 27, 2005 Edvard Munch’s Mermaid September 24–December 31, 2005 Jacob van Ruisdael: Dutch Master of Landscape October 23, 2005–February 5, 2006 Beauford Delaney: From New York to Paris November 13, 2005–January 29, 2006 Beauford Delaney in Context: Selections from the Permanent Collection November 13, 2005–February 26, 2006 Gaetano Pesce: Pushing the Limits November 18, 2005–April 9, 2006 Why the Wild Things Are: Personal Demons and Himalayan Protectors November 23, 2005–May 2006 Adventures in a Perfect World: North Indian Narrative Paintings, 1750–1850 November 23, 2005–May 2006 A Natural Attraction: Dutch and Flemish Landscape Prints from Bruegel to Rembrandt December 17, 2005–February 12, 2006 Recent Acquisitions: Prints and Drawings (working title) March 11–May 21, 2006 Andrew Wyeth: Memory and Magic March 29–July 16, 2006 Grace Kelly’s Wedding Dress April 2006 In Pursuit of Genius: Jean-Antoine Houdon and the Sculpted Portraits of Benjamin Franklin May 13–July 30, 2006 Photography at the Julien Levy Gallery (working title) June–September 2006 The Arts in Latin America, 1492--1820 Fall 2006 A Revolution in the Graphic -

AFAM 162 – African American History: from Emancipation to the Present Professor Jonathan Holloway

AFAM 162 – African American History: From Emancipation to the Present Professor Jonathan Holloway Lecture 10 – The New Negroes (continued) IMAGES Photograph of Alain Locke, with inscription to JWJ, June 20, 1926 . Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library; Bibliographic Record Number 39002036001643; Image ID# 3600164. "Aspects of Negro Life: The Negro in an African Setting," by Aaron Douglas (1934). Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Arts and Artifacts Division. "Into Bondage," by Aaron Douglas (1936). Corcoran Gallery of Art/Associated Press; The Evans-Tibbs Collection. "Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery Through Reconstruction," by Aaron Douglas (1934) Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Arts and Artifacts Division. Photograph of Langston Hughes (1925). JWJ MSS 26, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beineck Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Bibliographic Record Number 39002036122787, Image ID# 3612278. Photograph of Charlotte Mason (Date Unknown). Photographs of Blacks, collected chiefly by James Weldon Johnson and Carl Van Vechten, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Bibliographic Record Number 39002041692915, Image ID# 4169291. Photograph of Carl Van Vechten (includes inscription: "To Langston"). Photograph of Fredi Washington (wearing armband protesting lynching). Morgan and Marvin Smith (M & M Smith Studio) ca. 1938. Photograph of Mary McLeod Bethune, by Carl Van Vechten (6-Apr-49). Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library; Call Number JWJ Van Vechten; Bibliographic Record Number 2001889. Drawing to advertise Carl Van Vechten's book, Nigger Heaven, by Aaron Douglas. Beinecke; Call Number Art Object 1980.180.2; Bibliographic Record Number 39002035069476; Image ID# 3506947. -

Teaching Resource: Harlem Heroes

A TEACHING RESOURCe INTRODUCTIOn The photographs in this booklet capture a few of the leaders and personalities of the New Negro Movement, commonly referred to as the Harlem Renaissance. This flowering of creativity took place in the early part of the twentieth century in response to three major historical forces: the migration of millions of African Americans from the South to cities such as Chicago and New York, feeding new black communities in the North; the return of more than 350,000 black men to a segregated United States after O, write my name, O, write my name World War I; and a growing black middle class whose patronage sup- O, write my name... ported writers, musicians, and artists of color. Write my name when-a you get home... While the New Negro Movement engaged cities throughout the Yes, write my name in the book of life... northern United States, the photographs here will focus on Harlem be- The Angels in the heav’n going-to write my name. cause of the photographer: dance critic, socialite, and novelist Carl Van Vechten (1880–1964). He took up photography in 1932 and document —SPIRITUAL, UNDERGROUND RAILROAD ed people, black and white, in his expanding social circle. As a white patron of the arts in New York City, Van Vechten’s interest in Harlem’s creative class reflected a growing awareness of black culture within the white community. Scholar Alain Locke praised the New Negro Movement as a “definite enrichment of American art and letters and . the clarifying of our common vision of the social tasks ahead.” Open an early copy of The Crisis, the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), however, and it becomes clear: there was an ongoing debate about the definition and presentation of black identity. -

Decadence Revisited: Evelyn Waugh and the Afterlife of the 1890S

Decadence Revisited: Evelyn Waugh and the Afterlife of the 1890s Murray, A. (2015). Decadence Revisited: Evelyn Waugh and the Afterlife of the 1890s. Modernism/Modernity, 22(3), 593-607. https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2015.0052 Published in: Modernism/Modernity Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright © 2015 The Johns Hopkins University Press. This article first appeared in Modernism/Modernity Vol 22, Issue 3, September 2015, pp 593-607 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:30. Sep. 2021 'HFDGHQFH5HYLVLWHG(YHO\Q:DXJKDQGWKH$IWHUOLIH $OH[0XUUD\RIWKHV Modernism/modernity, Volume 22, Number 3, September 2015, pp. 593-607 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/mod.2015.0052 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mod/summary/v022/22.3.murray.html Access provided by Queen's University, Belfast (13 Oct 2015 11:24 GMT) Decadence Revisited: Evelyn Waugh and the Afterlife of the 1890s Alex Murray MODERNISM / modernity The young Evelyn Waugh’s first encounter with decadence VOLUME TWENTY TWO, came via his elder brother, Alec, in 1916: “He had a particular NUMBER THREE, relish at that time for the English lyric poets of the nineties; PP 593–607. -

The Jazz Age

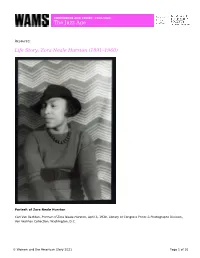

CONFIDENCE AND CRISES, 1920-1948 The Jazz Age Resource: Life Story: Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960) Portrait of Zora Neale Hurston Carl Van Vechten, Portrait of Zora Neale Hurston, April 3, 1938. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, Van Vechten Collection, Washington, D.C. © Women and the American Story 2021 Page 1 of 10 CONFIDENCE AND CRISES, 1920-1948 The Jazz Age Unidentified Woman With Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston Unidentified Woman With Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, 1927. Yale University Library, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. © Women and the American Story 2021 Page 2 of 10 CONFIDENCE AND CRISES, 1920-1948 The Jazz Age Zora Neale Hurston James Weldon Johnson, Zora Neale Hurston, 1927. Yale University Library, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. © Women and the American Story 2021 Page 3 of 10 CONFIDENCE AND CRISES, 1920-1948 The Jazz Age Zora Neale Hurston was born on January 7, 1891 in Eatonville, Florida. Eatonville was one of the first towns in the United States founded by Black citizens. Zora’s father was a minister who served three terms as Eatonville’s mayor. Zora attended the town’s school, where she studied the teachings of Booker T. Washington. She was greatly influenced by the philosophy that education, hard work, and perseverance could improve the lives of Black Americans. Zora’s mother died in 1904. Her father remarried and sent her to live with relatives. Frustrated by her situation, Zora took a job as a maid for a musical theater troupe in 1916. She traveled the country, learned about theater, and continued her studies by borrowing books from the performers. -

Fiscal Year 2019

Smithsonian Fiscal Year 2019 Submitted to the Committees on Appropriations Congress of the United States Smithsonian Institution Fiscal Year 2019 Budget Justification to Congress February 2018 SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Fiscal Year 2019 Budget Request to Congress TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Overview .................................................................................................... 1 FY 2019 Budget Request Summary ........................................................... 7 SALARIES AND EXPENSES Summary of FY 2019 Changes and Unit Detail ........................................ 11 Fixed Costs Salary and Related Costs ................................................................... 14 Utilities, Rent, Communications, and Other ........................................ 15 Summary of Program Changes ................................................................ 19 No-Year Funding ...................................................................................... 20 Object-Class Breakout ............................................................................. 20 Federal Resource Summary by Performance Objective and Program Category .............................................................................. 21 MUSEUMS AND RESEARCH CENTERS Grand Challenges and Interdisciplinary Research .............................. 23 National Air and Space Museum ........................................................ 25 Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory ............................................ 31 Major Scientific -

Oral History Interview with David Driskell, 2009 March 18-April 7

Oral history interview with David Driskell, 2009 March 18-April 7 Funding for this interview was provided by the Brown Foundation. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with David C. Driskell on March 10, 26, and April 7, 2009. The interview took place at the artist's home in Hyattsville, MD, and was conducted by Cynthia Mills for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Funding for this interview was provided by a grant from the Brown Foundation, Inc. David C. Driskell and Cynthia Mills have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview CYNTHIA MILLS: It's March 18, 2009, and we're at the Hyattsville, Maryland, home of David C. Driskell. David, could you start by telling us something about your origins—your parents and your childhood, growing up on a farm in North Carolina? DAVID C. DRISKELL: I was born June 7, 1931, in Eatonton, Georgia. Eatonton is a small town southeast of Macon, Georgia, in Putnam County. My father was a Methodist minister and my mother was a housewife. We lived in Eatonton for the first five and one half years of my life. In 1936 we moved to Appalachia in the western part of North Carolina. We were in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Rutherford County. -

Read an Excerpt

Toward the end of the 1920s, the NAACP journal, The Crisis, began to transform its “Poet’s Page” into a forum for white views of race, ranging from verses in the minstrel tradition to radical antiracist odes, often printed on the same page and without edito- rial comment. Although extreme, “A White Girl’s Prayer” spoke for many who longed for the exotic utopia they imagined Harlem could offer, just as Nancy Cunard’s “1930” voiced the belief of some white women that they could speak for, or as, blacks. 1 of 3_missanne_a_b_i_xxxii_1_356_4p.indd 16 7/18/13 9:54 AM introduction: in search of Miss Anne There were many white faces at the 1925 Opportunity awards dinner. So far they have been merely walk- ons in the story of the New Negro, but they became instrumental forces in the Harlem Renaissance. — Steven Watson, The Harlem Renaissance You know it won’t be easy to explain the white girl’s attitude, that is, so that her actions will seem credible. — Carl Van Vechten, Nigger Heaven Fania Marinoff in Harlem. did not set out to write this book. Some years back, in the course I of writing Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters, I needed, but could not find, information on the many white women Hurston knew and xvii 1 of 3_missanne_a_b_i_xxxii_1_356_4p.indd 17 7/18/13 9:54 AM Introduction: In Search of Miss Anne befriended in Harlem: hostesses, editors, activists, philanthropists, pa- trons, writers, and others. There was ample material about her black Harlem Renaissance contemporaries: “midwife” Alain Locke; leading intellectual W. -

Carl Van Vechten's Nigger Heaven: Envisioning and Reinventing American Transatlantic Bohemia in Harlem Edward Norman Tabor Lehigh University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lehigh University: Lehigh Preserve Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 2014 Carl Van Vechten's Nigger Heaven: Envisioning and Reinventing American Transatlantic Bohemia in Harlem Edward Norman Tabor Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Tabor, Edward Norman, "Carl Van Vechten's Nigger Heaven: Envisioning and Reinventing American Transatlantic Bohemia in Harlem" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1647. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Carl Van Vechten’s Nigger Heaven: Envisioning and Reinventing American Transatlantic Bohemia in Harlem by Edward N. Tabor A Thesis Presented to the Graduate and Research Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English Lehigh University November 30, 2013 Copyright Edward N. Tabor 2013 ii Thesis is accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in English. Carl Van Vechten’s Nigger Heaven: Envisioning and Reinventing American Transatlantic Bohemia in Harlem Edward N. Tabor ____________________________ Date Approved ___________________________ Amardeep Singh Advisor ____________________________ Scott Gordon Department Chairperson iii Acknowledgments This core of this project found its beginning with a course paper written for Professor Amardeep Singh’s Spring 2012 seminar, Transatlantic Modernism. The paper exists as a product of both the inspirational ideas of Deep’s teaching and my long- standing love of a modernism that cannot be fettered by national identity.