Anglican Identity and Mission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report from 1 August 2010

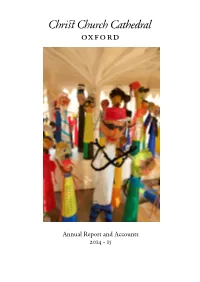

6 Annual Report and Accounts 2014 - 15 Annual Report August 2014 - July 2015 Introduction Christ Church Cathedral was, as ever, full of exciting activities and events during 2014 - 15, the most significant of which was the appointment of a new Dean, Martyn Percy, who replaced Christopher Lewis on his retirement in September 2014 after eleven years at the helm. Martyn became the forty-sixth Dean of Christ Church since its establishment by Henry VIII in 1546. This year’s cover illustration features the summer 2014 art installation of paper pilgrims produced by Summerfield School pupils displayed in our 15th century watching loft, situated between the Latin Chapel and the Lady Chapel. Worship There are between three and six regular Cathedral services every day of the year. Our congregations are varied: supporting a core of regular worshippers are a significant number of tourists visiting Christ Church from around the world. The Cathedral’s informal Sunday evening reflective service, After Eight, continued throughout the Michaelmas and Hilary terms and covered a wide range of topics. These included ‘A Particular Place’, focusing on a location of special spiritual significance to each of four speakers, ‘Enduring War … Engaging with Peace’, addressing present day conflicts, and ‘When I needed a Neighbour’, a series of dialogues on Christian ministry at the margins of modern life. There were many special events and services among them the following: • Our new year was ushered in with a reminder of the First World War. The centenary of the outbreak -

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD Christ Church was founded in 1546, and there had been a college here since 1525, but prior to the Dissolution of the monasteries, the site was occupied by a priory dedicated to the memory of St Frideswide, the patron saint of both university and city. St Frideswide, a noble Saxon lady, founded a nunnery for herself as head and for twelve more noble virgin ladies sometime towards the end of the seventh century. She was, however, pursued by Algar, prince of Leicester, for her hand in marriage. She refused his frequent approaches which became more and more desperate. Frideswide and her ladies, forewarned miraculously of yet another attempt by Algar, fled up river to hide. She stayed away some years, settling at Binsey, where she performed healing miracles. On returning to Oxford, Frideswide found that Algar was as persistent as ever, laying siege to the town in order to capture his bride. Frideswide called down blindness on Algar who eventually repented of his ways, and left Frideswide to her devotions. Frideswide died in about 737, and was canonised in 1480. Long before this, though, pilgrims came to her shrine in the priory church which was now populated by Augustinian canons. Nothing remains of Frideswide’s nunnery, and little - just a few stones - of the Saxon church but the cathedral and the buildings around the cloister are the oldest on the site. Her story is pictured in cartoon form by Burne-Jones in one of the windows in the cathedral. One of the gifts made to the priory was the meadow between Christ Church and the Thames and Cherwell rivers; Lady Montacute gave the land to maintain her chantry which lay in the Lady Chapel close to St Frideswide’s shrine. -

Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion

A (New) Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion Guillermo René Cavieses Araya Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Arts School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science February 2019 1 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Guillermo René Cavieses Araya The right of Guillermo René Cavieses Araya to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Guillermo René Cavieses Araya in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements No man is an island, and neither is his work. This thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of a lot of people, going a long way back. So, let’s start at the beginning. Mum, thank you for teaching me that it was OK for me to dream of working for a circus when I was little, so long as I first went to University to get a degree on it. Dad, thanks for teaching me the value of books and a solid right hook. To my other Dad, thank you for teaching me the virtue of patience (yes, I know, I am still working on that one). -

Chris Church Matters

Chris Church Matters MICHAELMAS TERM 2014 ISSUE 34 Editorial Contents In this Michaelmas edition we welcome our 45th Dean, the Very Revd Professor Dean’s Diary 1 Martyn Percy, who joined us in October after ten years as Principal of Ripon College Cuddesdon. We also say goodbye to our former Dean, Christopher Lewis, and his wife Goodbye from Chrsitopher Lewis 2 Rhona as they retire to the idyllic Suffolk coast. Much has been achieved in this year Cardinal Sins 6 of change, and we celebrate the successes of members past and present in this issue. If you have news of your own which you would like to share with the Christ Church Christ Church Cathedral Choir 8 community, we invite you to make a submission to the next Annual Report – details Cathedral News 9 of this can be found in College News. A new Christ Church website will be launched in the spring, and with this a new Christ Church People: digital platform for Christ Church Matters. If you would like to receive the magazine Phyllis May Bursill 10 digitally, please let us know. Conservation work We wish you a wonderful Christmas and New Year, and hope to see you in 2015. on the Music Collection 12 Simon Offen Leia Clancy Cathedral School 14 Christ Church Association Alumni Relations Officer Vice President and Deputy [email protected] College News 16 Development Director +44 (0)1865 286 598 [email protected] Boat Club News 18 +44 (0)1865 286 075 Association News 19 FORTHCOMING EVENTS Sensible Religion: A Review 29 Event booking forms are available to download at www.chch.ox.ac.uk/development/events/future The Paper Project at Ovalhouse 30 MARCH 2015 APRIL 2015 SEPTEMBER 2015 Robert Hooke’s Micrographia 32 14 March 24-26 April 12 September FAMILY PROGRAMME LUNCH MEETING MINDS: ALUMNI BOARD OF BENEFACTORS GAUDY Who should decide on war? 34 Christ Church WEEKEND IN VIENNA Christ Church Parents of current or former All are invited to join us for 18-20 September Christ Church Gardens 30 students are invited to lunch at three days of alumni activities MEETING MINDS: ALUMNI Christ Church. -

LOVE FREE OR DIE Production Notes

Reveal Productions 3UHVHQWV How the Bishop of New Hampshire is Changing the World 'LUHFWHGE\0DFN\$OVWRQ :RUOG3UHPLHUHDWWKH6XQGDQFH)LOP)HVWLYDO 86&LQHPD'RFXPHQWDU\&RPSHWLWLRQPLQXWHV 6XQGDQFH6FUHHQLQJV 0RQGD\-DQXDU\SP7HPSOH7KHDWUH3DUN&LW\ Tuesday, January 24, 1:30 pm, Holiday Village Cinema 3, Park City (Press & Industry) 7XHVGD\-DQXDU\SP3URVSHFWRU6TXDUH7KHDWUH3DUN&LW\ :HGQHVGD\-DQXDU\SP%URDGZD\&HQWUH&LQHPD6DOW/DNH&LW\ 7KXUVGD\-DQXDU\DP3URVSHFWRU6TXDUH7KHDWUH3DUN&LW\ 6DWXUGD\-DQXDU\SP0$5&3DUN&LW\ Publicity Contacts -RKQ0XUSK\ 'DULQ'DUDNDQDQGD 0XUSK\35 0XUSK\35 2IILFH 2IILFH &HOO &HOO MPXSUK\#PXUSK\SUFRP GGDUDNDQDQGD#PXUSK\SUFRP )RUPRUHLQIRUPDWLRQSOHDVHYLVLWKWWSZZZORYHIUHHRUGLHPRYLHFRP LOVE FREE OR DIE U.S. Documentary Competition/2012 Sundance Film Festival Page 2 SYNOPSIS Short /29()5((25',(LVDERXWDPDQZKRVHWZRGHILQLQJSDVVLRQVDUHLQGLUHFWFRQIOLFWKLVORYH IRU*RGDQGIRUKLVSDUWQHU0DUN*HQH5RELQVRQLVWKHILUVWRSHQO\JD\SHUVRQWREHFRPHD ELVKRSLQWKHKLVWRULFWUDGLWLRQVRI&KULVWHQGRP+LVFRQVHFUDWLRQLQWRZKLFKKHZRUHD EXOOHWSURRIYHVWFDXVHGDQLQWHUQDWLRQDOVWLUDQGKHKDVOLYHGZLWKGHDWKWKUHDWVHYHU\GD\VLQFH /29()5((25',(IROORZV5RELQVRQIURPVPDOOWRZQFKXUFKHVLQWKH1HZ+DPSVKLUH1RUWK &RXQWU\WR:DVKLQJWRQ¶V/LQFROQ0HPRULDOWR/RQGRQ¶V/DPEHWK3DODFHDVKHFDOOVIRUDOOWR VWDQGIRUHTXDOLW\±LQVSLULQJELVKRSVSULHVWVDQGRUGLQDU\IRONWRFRPHRXWIURPWKHVKDGRZVDQG FKDQJHKLVWRU\ Long /29()5((25',(LVDERXWDPDQZKRVHWZRGHILQLQJSDVVLRQVDUHLQGLUHFWFRQIOLFW KLVORYH IRU*RGDQGIRUKLVSDUWQHU0DUN*HQH5RELQVRQLVWKHILUVWRSHQO\JD\SHUVRQWREHFRPHD ELVKRSLQWKHKLVWRULFWUDGLWLRQVRI&KULVWHQGRP+LVFRQVHFUDWLRQLQWRZKLFKKHZRUHD -

Evangelism and Capitalism: a Reparative Account and Diagnosis of Pathogeneses in the Relationship

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary Portland Seminary 6-2018 Evangelism and Capitalism: A Reparative Account and Diagnosis of Pathogeneses in the Relationship Jason Paul Clark George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/gfes Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Jason Paul, "Evangelism and Capitalism: A Reparative Account and Diagnosis of Pathogeneses in the Relationship" (2018). Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary. 132. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/gfes/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Portland Seminary at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVANGELICALISM AND CAPITALISM A reparative account and diagnosis of pathogeneses in the relationship A thesis submitted to Middlesex University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jason Paul Clark Middlesex University Supervised at London School of Theology June 2018 Abstract Jason Paul Clark, “Evangelicalism and Capitalism: A reparative account and diagnosis of pathogeneses in the relationship.” Doctor of Philosophy, Middlesex University, 2018. No sustained examination and diagnosis of problems inherent to the relationship of Evangeli- calism with capitalism currently exists. Where assessments of the relationship have been un- dertaken, they are often built upon a lack of understanding of Evangelicalism, and an uncritical reliance both on Max Weber’s Protestant Work Ethic and on David Bebbington’s Quadrilateral of Evangelical priorities. -

Download File

Ordaining the Disinherited: What Women of Color Clergy Have to Teach Us About Discernment Tamara C. Plummer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Practical Theology at Union Theological Seminary April 16, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 Conceptual Frame..................................................................................................................... 5 The Episcopal Church ............................................................................................................ 10 Methodology - Story as scripture ............................................................................................. 14 Data: Description and Deconstruction ..................................................................................... 17 Bishop Emma .......................................................................................................................... 18 Rev. Sarai ................................................................................................................................. 25 Rev. Isabella ............................................................................................................................ 31 Rev. Julian ............................................................................................................................... 37 Rev. Juanita ............................................................................................................................ -

Doing the Lambeth Walk

DOING THE LAMBETH WALK The request We, the Bishops, Clergy and Laity of the Province of Canada, in Triennial Synod assembled, desire to represent to your Grace, that in consequence of the recent decisions of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the well-known case respecting the Essays and Reviews, and also in the case of the Bishop of Natal and the Bishop of Cape Town, the minds of many members of the church have been unsettled or painfully alarmed; and that doctrines hitherto believed to be scriptural, undoubtedly held by the members of the Church of England and Ireland, have been adjudicated upon by the Privy Council in such a way as to lead thousands of our brethren to conclude that, according to this decision, it is quite compatible with membership in the Church of England to discredit the historical facts of Holy Scripture, and to disbelieve the eternity of future punishment1 So began the 1865 letter from the Canadians to Charles Thomas Longley, Archbishop of Canterbury and Primate of All England. The letter concluded In order, therefore, to comfort the souls of the faithful, and reassure the minds of wavering members of the church, … we humbly entreat your Grace, …to convene a national synod of the bishops of the Anglican Church at home and abroad, who, attended by one or more of their presbyters or laymen, learned in ecclesiastical law, as their advisers, may meet together, and, under the guidance of the Holy Ghost, take such counsel and adopt such measures as may be best fitted to provide for the present distress in such synod, presided over by your Grace. -

Mountain Sky Area of the United Methodist Church I Write to You As a Brother in Christ, and a Bishop in the Episcopal Churc

To: Mountain Sky Area of The United Methodist Church I write to you as a brother in Christ, and a Bishop in the Episcopal Church. I am not a member of your church (although I attended a small Methodist church with my grandmother), so I hope you won’t think me presumptuous if I share a few thoughts with you about the upcoming decisions re: Bishop Karen Oliveto. As a Bishop, I know well the tension between the stewardship of the church and the call of the Gospel. As a Bishop, it is my solemn calling to receive the 2,000 years of teaching and wisdom of the Church, and to ensure that it is passed on intact to the next generation. A second, implied responsibility is preservation of the institution. In my decade of serving as the Bishop of New Hampshire, I learned and came to believe that in order to be faithful to each of those responsibilities, I had to be true to their meaning and intention, rather than their literal words. Often, I found that in order to follow the command to love my neighbor, I had to take some risks with the institution. Our faith is a living, breathing thing – not an unchanging set of beliefs, unresponsive to what God is teaching us along the way. There was a time when many people in your denomination and mine used Holy Scripture to justify slavery, forbid interracial marriage, and denigrate women as inferior to men. We now look at those expressions of the historic “faith” as cruel misperceptions of God’s will. -

The Anglican Debacle: Roots and Patterns

The Anglican Debacle: Roots and Patterns No Golden Age The first thing to note about the crisis the Anglican Communion is facing today is that it has been coming for a very long time. I remember almost twenty years ago reading an article by Robert Doyle in The Briefing entitled ‘No Golden Age’.1 (It’s shocking that it is actually so long ago!) The gist of the article was that the idea of a golden age of Anglicanism, in which biblical patterns of doctrine and practice were accepted by the majority, is nothing but an illusion. Biblical Christianity has always struggled under the Anglican umbrella. At some times it did better than at others, but there was never a time when evangelical Anglicanism, even of the more formal prayer book kind, was uniformly accepted or endorsed by the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Latimer, Ridley and Cranmer were, after all, burnt at the stake with the consent of most of the rest of the bishops in Mary’s church. The Puritans who stayed within the Church of England suffered at the hands of Elizabeth I, and William Laud and others made life increasingly difficult for them after Elizabeth’s death. The re-establishment of the Church of England following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 was never a determined return to the Reformed evangelical version of Archbishop Cranmer, but a compromise designed to exclude anything that resembled Puritanism. Wesley was hunted out of the established church. Whitfield had to preach in the open air when pulpits were closed to him. However, the real seeds of the problem we now face lie in the nineteenth century. -

AAC Timeline

THE ANGLICAN REALIGNMENT Timeline of Major Events 1977 Continuing Anglican Movement is 1987 & 1989 founded over the mainstream ordination of women to the priesthood. TEC Panel of bishops dismiss heresy Composed of several breakaway charges against Bishop Spong of Anglican jurisdictions no longer in Newark; he rejects among other things communion with Canterbury, some of the incarnation, atonement, these will join the Anglican Church in resurrection, the second coming of North America (ACNA) during the Christ and the Trinity. realignment. 1994 Global South Anglicans (GSA) begin meeting and communicating in earnest between its members regarding the growing liberal theological trends in the Anglican Communion. 1996 1998 The American Anglican Council (AAC) is founded by Bp. David Anderson as a Lambeth Council of Bishops takes place response to unbiblical teachings in TEC under Canterbury’s leadership, during and the larger Anglican Communion. which Anglican bishops overwhelmingly Begins organizing in earnest hundreds (567-70) uphold the biblically orthodox of clergy and lay delegates to the TEC definition of marriage and sexuality in Triennial General Conventions (1997, Lambeth Resolution 1.10. Bishops from 2000, 2003, 2006 and 2009) to stand up TEC and ACoC immediately protest that for “the faith once delivered to the they will not follow Biblical teaching. saints.” (Jude 3) 2000 Anglican Mission in the Americas (AMiA) is founded in Amsterdam, Netherlands, due to theologically liberal developments in the Episcopal Church 2002 (TEC) and the Anglican Church of Canada (ACoC) under the primatial Diocese of New Westminster, Canada, oversight of Rwanda and South East authorizes rite of blessing for same-sex Asia. -

V. Gene Robinson IX Bishop of New Hampshire

V. Gene Robinson IX Bishop of New Hampshire Bishop V. Gene Robinson was elected Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New Hampshire on June 7, 2003, having served as Canon to the Ordinary (Assistant to the Bishop) for almost 18 years. He was consecrated on All Saints Sunday, November 2, 2003, and was invested as the Ninth Bishop of New Hampshire on March 7, 2004. He is the first openly gay priest to be elected bishop in the Anglican communion. Bishop Robinson was born in Lexington, Kentucky on May 29, 1947. He is a 1969 graduate of the University of the South, Sewanee, Tennessee with a B.A. in American Studies/History. He completed the M. Div. degree in 1973 at the General Theological Seminary in New York, was ordained deacon, then priest, serving as Curate at Christ Church Ridgewood, New Jersey. He has co-authored three AIDS education curricula for youth and adults. Gene has done AIDS work in the United States and in Africa (Uganda and South Africa). He holds two honorary doctorates and has received numerous awards from national civil rights organizations. Clergy wellness has long been a focus of Gene’s ministry. In 2006 author Elizabeth Adams wrote “Going to Heaven”, the life and election of V. Gene Robinson. His story is featured in the 2007 feature-length documentary, “For the Bible Tells Me So”, a film by Daniel Karslake. In 2008 Bishop Robinson wrote “In the Eye of the Storm” . a “book about who I am.” Bishop Robinson has received many awards, and made an enormous impact on the GLBT community.