Mci Social Sector Working Paper Series N 5/2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

55-68 Impact of Area Enclosures on Density

pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com East African Journal of Sciences (2007) Volume 1 (1) 55-68 Impact of Area Enclosures on Density and Diversity of Large Wild Mammals: The Case of May Ba’ati, Douga Tembien District, Central Tigray, Ethiopia Mastewal Yami1*, Kindeya Gebrehiwot1, M. Stein2, and Wolde Mekuria1 1Department of Land Resources Management and Environmental Protection, Mekelle University, P O Box 231, Mekelle, Ethiopia 2University of Life Sciences, Norway Abstract: In Ethiopian highlands, area enclosures have been established on degraded areas for ecological rehabilitation. However, information on the importance of area enclosures in improving wild fauna richness is lacking. Thus, this study was conducted to assess the impact of enclosures on density and diversity of large wild mammals. Direct observations along fixed width transects with three timings, total counting with two timings, and pellet drop counts were used to determine population of large wild mammals. Regression analysis and ANOVA were used to test the significance of the relationships among age of enclosures, canopy cover, density and diversity of large wild mammals. The enclosures have higher density and diversity of large wild mammals than adjacent unprotected areas. The density and diversity of large wild mammals was higher for the older enclosures with few exceptions. Diversity of woody species also showed strong relationship (r2 = 0.77 and 0.92) with diversity of diurnal and nocturnal wild mammals. Significant relationship (at p<0.05) was observed between age and density as well as among canopy cover, density and diversity of large nocturnal wild mammals. -

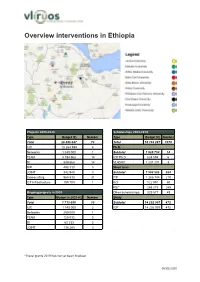

Overview Interventions in Ethiopia

Overview interventions in Ethiopia Projects 2003-2020 Scholarships 2003-2019 Type Budget (€) Number Type Budget (€) Number Total 26 356 647 73 Total 18 103 287 1070 IUC 18 264 999 4 Ph.D. Networks 1 040 000 1 Subtotal 1 825 794 14 TEAM 4 194 968 14 ICP Ph.D. 624 594 6 SI 849 868 14 VLADOC 1 201 201 8 RIP 498 330 5 Short term JOINT 342 940 3 Subtotal 1 984 585 584 Crosscutting 965 833 31 ITP 1 265 744 210 ICT Infrastructure 199 709 1 KOI 122 991 60 REI* 266 273 265 Ongoing projects in 2020 Other scholarships 329 577 49 Type Budget in 2020 (€) Number Study Total 1 713 650 10 Subtotal 14 292 907 472 IUC 1 140 000 2 ICP 14 292 907 472 Networks 250 000 1 TEAM 125 032 2 SI 62 333 2 JOINT 136 285 3 *Travel grants 2019 has not yet been finalised. 06/02/2020 List of projects 2003-2020 Flemish Total Type Runtime Title Local promoter Local institution promoter budget (€) J. Deckers IUC 2003-2014 Institutional University Cooperation with Mekelle University (MU) (phase 1, 2 and phase out) K. Gebrehiwot Mekelle University 6.655.000 (KUL) L. Duchateau IUC 2005-2018 Institutional University Cooperation with Jimma University (JU) (phase 1 and 2, and phase out) K. Tushune Jimma University 6.855.000 (UG) Institutional University Cooperation with Arba Minch University (AMU) (pre-partner programme and IUC 2015-2021 R. Merckx (KUL) G.G. Sulla Arba Minch University 3.000.000 phase 1) Institutional University Cooperation with Bahir Dar University (BDU) (pre-partner programme and IUC 2015-2021 J. -

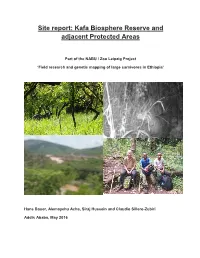

Site Report: Kafa Biosphere Reserve and Adjacent Protected Areas

Site report: Kafa Biosphere Reserve and adjacent Protected Areas Part of the NABU / Zoo Leipzig Project ‘Field research and genetic mapping of large carnivores in Ethiopia’ Hans Bauer, Alemayehu Acha, Siraj Hussein and Claudio Sillero-Zubiri Addis Ababa, May 2016 Contents Implementing institutions and contact persons: .......................................................................................... 3 Preamble ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Objective ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Description of the study site ......................................................................................................................... 5 Kafa Biosphere Reserve ............................................................................................................................ 5 Chebera Churchura NP .............................................................................................................................. 5 Omo NP and the adjacent Tama Reserve and Mago NP .......................................................................... 6 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................ -

Education Needs Assessment for Mekelle City, Ethiopia

MCI SOCIAL SECTOR WORKING PAPER SERIES N° 5/2009 EDUCATION NEEDS ASSESSMENT FOR MEKELLE CITY, ETHIOPIA Prepared by Jessica Lopez , Moumié Maoulidi and MCI September 2009 NB: This needs assessment was initially researched and prepared by Jessica Lopez. It was revised and updated by MCI Social Sector Research Manager Moumié Maoulidi who also ran the EPSSIm model simulations and wrote the introduction and the conclusion and recommendations section and revised the EPPSIm results section. MCI intern Michelle Reddy assisted in reviewing and updating the report. The report also benefitted from input provided by MCI Social Sector Specialist in Ethiopia, Aberash Abay. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am most grateful to the Millennium Cities Initiative at Columbia University’s Earth Institute for enabling me to conduct educational research in Ethiopia for six weeks during the summer of 2008. I had a great deal of support from Ms. Aberash Abay, MCI Social Sector Specialist for Mekelle, who provided invaluable information on where and how to gather the information I needed for my work. Ms. Abay also facilitated my entrée into government agencies and my visits with local school administrators and officials. The substantive knowledge, advice and statistical data provided by Mr. Ato Gebremedihn, Head of Statistics at the Tigray Regional Education Bureau, were crucial to the production of this report. Mr. Ato Gebremedihn has continued to provide data and documentation during the last six months, as this report was being written. I would especially like to thank all of the local officials, administrators and teachers who took the time to meet with me and share information. -

Referral Systems for Preterm, Low Birth Weight, and Sick Newborns in Ethiopia: a Qualitative Assessment Alula M

Teklu et al. BMC Pediatrics (2020) 20:409 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02311-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Referral systems for preterm, low birth weight, and sick newborns in Ethiopia: a qualitative assessment Alula M. Teklu1, James A. Litch2* , Alemu Tesfahun3, Eskinder Wolka4, Berhe Dessalegn Tuamay5, Hagos Gidey6, Wondimye Ashenafi Cheru7, Kirsten Senturia2, Wendemaghen Gezahegn1 and And the Every Preemie–SCALE Ethiopia Implementation Research Collaboration Group Abstract Background: A responsive and well-functioning newborn referral system is a cornerstone to the continuum of child health care; however, health system and client-related barriers negatively impact the referral system. Due to the complexity and multifaceted nature of newborn referral processes, studies on newborn referral systems have been limited. The objective of this study was to assess the barriers for effective functioning of the referral system for preterm, low birth weight, and sick newborns across the primary health care units in 3 contrasting regions of Ethiopia. Methods: A qualitative assessment using interviews with mothers of preterm, low birth weight, and sick newborns, interviews with facility leaders, and focus group discussions with health care providers was conducted in selected health facilities. Data were coded using an iteratively developed codebook and synthesized using thematic content analysis. Results: Gaps and barriers in the newborn referral system were identified in 3 areas: transport and referral communication; availability of, and adherence to newborn referral protocols; and family reluctance or refusal of newborn referral. Specifically, the most commonly noted barriers in both urban and rural settings were lack of ambulance, uncoordinated referral and return referral communications between providers and between facilities, unavailability or non-adherence to newborn referral protocols, family fear of the unknown, expectation of infant death despite referral, and patient costs related to referral. -

Mekelle University FINAL THESIS

MEKELLE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT Community Based Ecotourism Development as a Viable Strategy for Sustainable Natural Resource Management: Opportunities and Challenges. The Case of Borena-Saynt Park: South Wollo, Ethiopia. By Amogne Asfaw Eshetu (ID.No.FBE/ PR/0005/00) A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree (MA) in Development Studies Advisor: Gebremedihn Yihdego (Assistant professor) Co-advisor: Micheal Tsegay (MSc) February, 2010 Mekelle, Ethiopia Declaration This is to certify that this thesis entitled “ Community Based Ecotourism Development as a Viable Strategy for Sustainable Natural Resource Management: Opportunities and Challenges. The case of Borena-Saynt Park: South Wollo, Ethiopia ” submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MA., in Development Studies to the College of Business and Economics, Mekelle University, through the Department of Management, done by Mr. Amogne Asfaw Eshetu , Id.No.FBE/ PR/0005/00 is an authentic work carried out by him under my guidance. The matter embodied in this project work has not been submitted earlier for award of any degree or diploma to the best of my knowledge and belief. Name of the student Amogne Asfaw Eshetu Signature__________________Date ________ Name of the Advisors Gebremedihn Yihdego (Assistant professor) Signature__________Date ________ Michael Tsegaye (MSc) Signature_______________ Date ________________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am indebted to a number of individuals; without whose efforts this study would not have been completed in time. First and foremost I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisors Gebremedihn Yihdego (Assistant professor) and Ato Micheal Tsegay for their exhaustive review and constructive comments right from the inception up to the finalization of this thesis. -

Education Needs Assessment for Mekelle, Ethiopia

MCI SOCIAL SECTOR WORKING PAPER SERIES N° 4 EDUCATION NEEDS ASSESSMENT FOR MEKELLE CITY, ETHIOPIA Prepared by Jessica Lopez, Moumié Maoulidi and MCI September 2009 2 NB: This needs assessment, initially researched and prepared by Jessica Lopez, was revised and updated by MCI Social Sector Research Manager Moumié Maoulidi, who also ran the EPSSim model simulations, revised the section on the EPPSim results, conducted data validation sessions in Mekelle with the relevant municipal and regional officials and is responsible for the introduction, conclusion and recommendations. MCI intern Michelle Reddy assisted in reviewing and updating the report, which also benefitted from input provided and consultations facilitated by MCI Social Sector Specialist in Ethiopia, Aberash Abay. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am most grateful to the Millennium Cities Initiative at Columbia University’s Earth Institute for enabling me to conduct educational research in Ethiopia for six weeks during the summer of 2008. I had a great deal of support from Ms. Aberash Abay, MCI Social Sector Specialist for Mekelle, who provided invaluable information on where and how to gather the information I needed for my work. Ms. Abay also facilitated my entrée into government agencies and my visits with local school administrators and officials. The substantive knowledge, advice and statistical data provided by Mr. Ato Gebremedihn, Head of Statistics at the Tigray Regional Education Bureau, were crucial to the production of this report. Mr. Ato Gebremedihn has continued to provide data and documentation in the course of recent months, as this report was being written. I would especially like to thank all of the local officials, administrators and teachers who took the time to meet with me and to share information. -

Situation Report Last Updated: 8 Mar 2021

ETHIOPIA - TIGRAY REGION HUMANITARIAN UPDATE Situation Report Last updated: 8 Mar 2021 HIGHLIGHTS (8 Mar 2021) The Prime Minister, on 3 March, announced that aid agencies can operate in the region by providing a notification to the Ministry of Peace. Following this significant development, organizations have begun notifying the Ministry, and the humanitarian community is working to urgently improve access to rural areas. Violence and lack of assistance in rural areas continue to drive displacement of people searching for safety and aid in the main towns across Tigray. Partners continue to receive reports of looting and grave violence against civilians, including extrajudicial killing, rapes and other forms of gender-based The boundaries and names shown and the designations violence. used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. © OCHA Disruptions in basic services, such as communications, banking services and electricity, pose serious challenges to humanitarian efforts, while putting people further at risk. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (2020) CONTACTS Saviano Abreu 950,000 1.3M $1.3B $732.4M Communications Team Leader, People in need of aid Projected additional Required Received Regional Office for Southern & Eastern before the conflict people to need aid Africa A n [email protected] d , r 59% e ! y j r j e 61,719 $34M r ! r Progress Alexandra de Sousa o d Refugees in Sudan Unmet requirements S n A Deputy Head of Office, OCHA Ethiopia since 7 November for the Response Plan [email protected] FTS: https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/9 36/summary BACKGROUND (8 Mar 2021) SITUATION OVERVIEW The humanitarian situation in Tigray remains extremely concerning, while reports of intensified fighting and lack of assistance in rural areas continue to drive displacements of people across the Region. -

Mekelle University Department of Management College of Business and Economics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IDS OpenDocs Mekelle University Department of Management College of Business and Economics Analysis of the Challenges and Prospects of Students’ Completion of Primary Education (The case of Asgede Tsimbla District, Northwestern Tigray) By Birhane Gidey A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Management in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Development Studies Advisor: Tewelde Mezgobo (Ass.Prof.) Co-advisor: Dereje T/Mariam (MA, MSAD, MSAF) May 2011 Mekelle DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university and that all sources of material used for this thesis have been dully acknowledged. Birhane Gidey Redehey ______________________________________ May 2011 The thesis has been submitted for examination with my approval as a university advisor. Tewelde Mezgobo (Assistant Prof.) ___________________________________________ May 2011 The thesis has been submitted for examination with my approval as a university co-advisor. Derege T/Mariam (MA, MSAD, MSAF) _______________________________________________ May 2011 Mekelle University ii CERTIFICATION This is to certify that this thesis entitled ―Analysis of the Challenges and Prospects of Students’ Completion of Primary Education, the Case of Asgede Tsimbla District‖ submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MA, in Development Studies to the College of Business and Economics, Mekelle University, through the Department of Management, done by Mr. /Ms. Birhane Gidey Redehey, Id.No. CBE/PR/094/02 is an authentic work carried out by him/her under my guidance. -

Horn of Africa Civil Society Forum Report on Tigray

THE HORN OF AFRICA CIVIL SOCIETY FORUM REPORT ON TIGRAY Contents THE HORN OF AFRICA CIVIL SOCIETY FORUM REPORT ON TIGRAY .................................................. 0 About the Horn of Africa Civil Society Forum (HoACS Forum) .............................................................. 2 FORUM MEMBERS........................................................................................................................... 2 Report on the Breaches of International Law ......................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology and Standard of Proof ................................................................................................ 11 Context ............................................................................................................................................... 12 Events occurring before the 4th of November 2020 .......................................................................... 12 Events occurring after the 4th of November 2020. ............................................................................ 14 International Legal Framework Applicable to the Tigray Crisis ........................................................ 17 Major Violations .................................................................................................................................. 18 Starvation as a weapon of -

Status of Lion (Panthera Leo) and Spotted Hyena (Crocuta Crocuta) in Nechisar National Park, Ethiopia

Status of Lion (Panthera leo) and Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta) in Nechisar National Park, Ethiopia Gidey Yirga1*, Fikirte Gebresenbet 1, Jozef Deckers 2 and Hans Bauer 3 1Department of Biology, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Ethiopia (*[email protected]) 2KU Leuven University, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Celestijnenlaan 200E, B-3001 Heverlee, Belgium 3Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Zoology, University of Oxford. Recanati-Kaplan Centre, Tubney House, Tubney OX13 5QL, UK ABSTRACT Globally large carnivores are in decline due to a combination of habitat degradation and direct human persecution. A survey was conducted in Nechisar national park, Southern Ethiopia to investigate the population status of lion (Panthera leo) and hyena (Crocuta crocuta). Eleven callups were performed; a total of two adult male lions and six spotted hyenas responded. Estimates give a lion density of between 2 and 5 per 100 km2 or a total population estimate of 7 to 23 lions and a hyena density of between 4 to 8 hyenas per 100 km2 or a total population estimate of 17 to 34 hyenas. These estimates include extrapolation to a heavily encroached area where large carnivores are unlikely to occur. The lion population is probably limited to the visually confirmed four individuals. The carrying capacity of Nechisar national park, excluding livestock, is 21 lions and 48 hyenas. The resident agro-pastoral communities who are living with their livestock inside and adjacent to the national park are in conflict with carnivores. This might account for the low density of lion and hyena in the park, and perhaps might result in local extinction within a few years. -

May 27-28, 2016 Ethiopia, Africa

May 27-28, 2016 Ethiopia, Africa www.wmich.edu/africacenter International research abstracts submitted to the 9th International Conference on African Development hosted by Western Michigan University’s Center for African Development Policy Research and other WMU colleges and departments in collaboration with several universities in Ethiopia and Africa. Determinants of Changes in Cropping Patterns and Land-Use in Ethiopia: Evidence from Seven Rounds (1994-2009) of Survey Data. Adugna Lemi and Michael Denney, University of Massachusetts, Boston, USA. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Climate change and international trade are rapidly changing the world. Both phenomena have day-to-day impacts that reach every corners of the globe. Farming communities in developing countries are not exceptions, as both climate change and dynamics of international trade have significant repercussions on crop yield, food prices, crop choices, and land-use patterns. Of particular importance to these communities is the lack of (or very limited) support they receive from their governments or from international development agencies to cope with the consequences of climate changes and changes in international trade patterns. Changing cropping and land use patterns are just two of the ways that such communities try to adapt to their changing environments. Understanding the inner workings of how climate change and international trade affect such farming communities, and how they have adjusted through changes in cropping pattern and land use, provide important and necessary insight for policy makers and donors interested in assisting these communities. The present study proposes to do such an analysis for farming communities in Ethiopia. Specifically, we will examine how farming communities in Ethiopia have changed their land use and cropping patterns, among other possible adaptations, over the past fifteen years as a result of exposure to climate change and increased international trade.