Gender Based Violence in Tigray 08 March 2021 Special Briefing No. 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Situation Report EEPA HORN No. 59 - 18 January 2021

Situation Report EEPA HORN No. 59 - 18 January 2021 Europe External Programme with Africa is a Belgium-based Centre of Expertise with in-depth knowledge, publications, and networks, specialised in issues of peace building, refugee protection and resilience in the Horn of Africa. EEPA has published extensively on issues related to movement and/or human trafficking of refugees in the Horn of Africa and on the Central Mediterranean Route. It cooperates with a wide network of Universities, research organisations, civil society and experts from Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Djibouti, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Uganda and across Africa. Reported war situation (as confirmed per 17 January) - According to Sudan Tribune, the head of the Sudanese Sovereign Council, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, disclosed that Sudanese troops were deployed on the border as per an agreement with the Ethiopian Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, arranged prior to the beginning of the war. - Al-Burhan told a gathering about the arrangements that were made in the planning of the military actions: “I visited Ethiopia shortly before the events, and we agreed with the Prime Minister of Ethiopia that the Sudanese armed forces would close the Sudanese borders to prevent border infiltration to and from Sudan by an armed party.” - Al-Burhan stated: "Actually, this is what the (Sudanese) armed forces have done to secure the international borders and have stopped there." His statement suggests that Abiy Ahmed spoke with him about the military plans before launching the military operation in Tigray. - Ethiopia has called the operation a “domestic law and order” action to respond to domestic provocations, but the planning with neighbours in the region on the actions paint a different picture. -

Social-Media-Health

February 15th - March 15th, 2021 Social Media Health Report in Ethiopia A report compiled by the Center for Advancement of Rights and Democracy (CARD) contents Introduction 1 Findings 2 Key Issues of the Month 2 EZEMA’s election-related concerns (February 15th) 2 OLF’s statement regarding the upcoming election (February 19th) 4 The killing of Yemane Nigusse, leader of the fenqil movement (February 20th ) 5 #StarvingForJustice and #OromoProtests (February 22nd) 9 Grant of permission for international media outlets to cover Tigray[1] region. (24th February) 10 Security concerns in Tigray Region (26th of February) 13 Killings in Horogudru welega zone (March 10th) 22 Conclusion 24 Social Media Health Report in Ethiopia February 15 - March 15, 2021 A report by the Center for Advancement of Rights and Democracy (CARD) Introduction This social media health report construes the monitoring conducted in the days between the 15th of February 2021 through the 15th of March 2021. The Health Report is aimed at assessing the key issues on social media, the overall dynamics of hate speech in the country, and what they mean to the socio-political development of Ethiopia. The monitoring of this month includes the overall assessment of social media activities through the platform of Crowd Tangle and Brandwatch. Key issues are determined based on the degree of interaction and the attention it received on social media. SOCIAL MEDIA HEALTH REPORT 1 Findings Key Issues of the Month During this period, the following issues have been widely discussed: • EZEMA’s election-related concerns (February 15th) The Ethiopian Citizens for Social Justice (EZEMA) party began its election campaign in Addis Ababa on the 15th of February. -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

Joanne's Testimony

Joanne’s Testimony My roots in the Tigray province of Ethiopia are long and deep. My grandmother, Bizunesh Atsbeha, came from a long royal lineage in the northern region of Tigray, Ethiopia called Agamé, and she lived there until she passed away a few years ago. I spent many years visiting with family there and I developed deep friendships and connections in the region. I am very “Toronto”, I’m mixed; my dad is half Ethiopian (born and raised there), and my mom is a white Canadian with British and Scottish roots. During my time in Ethiopia, and especially in Tigray I found that even in communities experiencing abject poverty, even in households that had no knowledge of my Ethiopian connection or my grandmother’s lineage, I was always welcomed by open hearts into open homes. Ethiopia has spent years battling the bad press of famine from the 1980s and there is much to be celebrated about the country. It is home to the Aksumite Empire, one of the greatest empires in history. It boasts the origin of coffee, the source of the Blue Nile, a delicious culinary culture, a diverse landscape and a rich cultural history. It is one of the two countries on the continent of Africa to have never been colonized, and it’s the site of an incredibly important battle in global history, the Battle of Adwa, which repelled a colonizing force and became a symbol of strength in Africa—helping to mobilize black communities around the world. Ethiopia is also a religious nation, primarily composed of Christian and Muslim people. -

55-68 Impact of Area Enclosures on Density

pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com East African Journal of Sciences (2007) Volume 1 (1) 55-68 Impact of Area Enclosures on Density and Diversity of Large Wild Mammals: The Case of May Ba’ati, Douga Tembien District, Central Tigray, Ethiopia Mastewal Yami1*, Kindeya Gebrehiwot1, M. Stein2, and Wolde Mekuria1 1Department of Land Resources Management and Environmental Protection, Mekelle University, P O Box 231, Mekelle, Ethiopia 2University of Life Sciences, Norway Abstract: In Ethiopian highlands, area enclosures have been established on degraded areas for ecological rehabilitation. However, information on the importance of area enclosures in improving wild fauna richness is lacking. Thus, this study was conducted to assess the impact of enclosures on density and diversity of large wild mammals. Direct observations along fixed width transects with three timings, total counting with two timings, and pellet drop counts were used to determine population of large wild mammals. Regression analysis and ANOVA were used to test the significance of the relationships among age of enclosures, canopy cover, density and diversity of large wild mammals. The enclosures have higher density and diversity of large wild mammals than adjacent unprotected areas. The density and diversity of large wild mammals was higher for the older enclosures with few exceptions. Diversity of woody species also showed strong relationship (r2 = 0.77 and 0.92) with diversity of diurnal and nocturnal wild mammals. Significant relationship (at p<0.05) was observed between age and density as well as among canopy cover, density and diversity of large nocturnal wild mammals. -

Disinformation in Tigray

Disinformation in Tigray: Manufacturing Consent For a Secessionist War May 2021 Cover Photo: TPLF leader “Aboy” (father) Sebhat Nega captured by Ethiopian National Defense Forces on January 8, 2021. (Courtesy of Ethiopian News Agency) Acknowledgements The preparers of this report by New Africa Institute would like to thank officials from the African Union, United Nations, Ethiopia and Eritrea for their assistance. New Africa Institute 601 West 26th Street Suite 325-53 New York, NY 10001 © New Africa Institute, 2021. Published on May 9, 2021. This material is offered free of charge for personal and non-commercial use, provided the source is acknowledged. For commercial or any other use, prior written permission must be obtained from the New Africa Institute. In no case may this material be altered, rented or sold. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORICAL CONTEXT ................................................................................................................................................................... III LOWERING EVIDENTIARY STANDARDS ..................................................................................................................................... 8 “COMMUNICATIONS BLACKOUT” .................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 “RESTRICTED HUMANITARIAN ACCESS” .................................................................................................................................................................. -

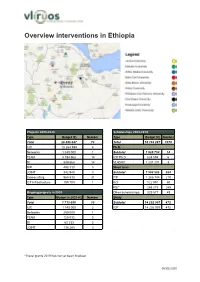

Overview Interventions in Ethiopia

Overview interventions in Ethiopia Projects 2003-2020 Scholarships 2003-2019 Type Budget (€) Number Type Budget (€) Number Total 26 356 647 73 Total 18 103 287 1070 IUC 18 264 999 4 Ph.D. Networks 1 040 000 1 Subtotal 1 825 794 14 TEAM 4 194 968 14 ICP Ph.D. 624 594 6 SI 849 868 14 VLADOC 1 201 201 8 RIP 498 330 5 Short term JOINT 342 940 3 Subtotal 1 984 585 584 Crosscutting 965 833 31 ITP 1 265 744 210 ICT Infrastructure 199 709 1 KOI 122 991 60 REI* 266 273 265 Ongoing projects in 2020 Other scholarships 329 577 49 Type Budget in 2020 (€) Number Study Total 1 713 650 10 Subtotal 14 292 907 472 IUC 1 140 000 2 ICP 14 292 907 472 Networks 250 000 1 TEAM 125 032 2 SI 62 333 2 JOINT 136 285 3 *Travel grants 2019 has not yet been finalised. 06/02/2020 List of projects 2003-2020 Flemish Total Type Runtime Title Local promoter Local institution promoter budget (€) J. Deckers IUC 2003-2014 Institutional University Cooperation with Mekelle University (MU) (phase 1, 2 and phase out) K. Gebrehiwot Mekelle University 6.655.000 (KUL) L. Duchateau IUC 2005-2018 Institutional University Cooperation with Jimma University (JU) (phase 1 and 2, and phase out) K. Tushune Jimma University 6.855.000 (UG) Institutional University Cooperation with Arba Minch University (AMU) (pre-partner programme and IUC 2015-2021 R. Merckx (KUL) G.G. Sulla Arba Minch University 3.000.000 phase 1) Institutional University Cooperation with Bahir Dar University (BDU) (pre-partner programme and IUC 2015-2021 J. -

Read Full Situation Report…

1 2 S I T U A T I O N 0 2 Y A R E P O R T M P R E P A R E D B Y P A G E 0 2 E X E C U T I V E S U M M A R Y On November 4, 2020, the unelected Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed began what his administration has called a “law enforcement operation” against the rightfully elected Tigray regional government. By his own admission, Abiy mobilized the Ethiopian National Defence Forces (ENDF), special forces from neighboring regions (Amhara Special Forces and Afar Special Forces), and most alarmingly, invited the army of a neighboring country - Eritrea - to wage war against the people of Tigray. Despite the repeated assertions by the Ethiopian government that this is a domestic “law enforcement operation,” the campaign against Tigray is clearly a regional war involving various domestic and international actors. And despite urgent calls by the international community, the Ethiopian government has refused to provide unhindered access to aid organizations, UN investigators or mediators. In the six months since the war was officially declared, the over 7 million residents of Tigray have been subject to innumerable human rights violations, including massacres, extra-judicial executions, forced displacement, starvation, and lack of access to health care and essential services. A list of 1,900 Tigrayans murdered in approximately 150 mass killings was recently compiled by University of Ghent professor Jan Nyssen. He has illuminated a harrowing pattern: retaliatory killings of civilians by Eritrean or Ethiopian forces after losing a battle [1]. -

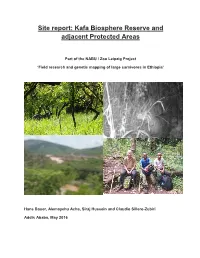

Site Report: Kafa Biosphere Reserve and Adjacent Protected Areas

Site report: Kafa Biosphere Reserve and adjacent Protected Areas Part of the NABU / Zoo Leipzig Project ‘Field research and genetic mapping of large carnivores in Ethiopia’ Hans Bauer, Alemayehu Acha, Siraj Hussein and Claudio Sillero-Zubiri Addis Ababa, May 2016 Contents Implementing institutions and contact persons: .......................................................................................... 3 Preamble ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Objective ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Description of the study site ......................................................................................................................... 5 Kafa Biosphere Reserve ............................................................................................................................ 5 Chebera Churchura NP .............................................................................................................................. 5 Omo NP and the adjacent Tama Reserve and Mago NP .......................................................................... 6 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................ -

Situation Report EEPA HORN No. 53 - 12 January 2021

Situation Report EEPA HORN No. 53 - 12 January 2021 Europe External Programme with Africa is a Belgium-based Centre of Expertise with in-depth knowledge, publications, and networks, specialised in issues of peace building, refugee protection and resilience in the Horn of Africa. EEPA has published extensively on issues related to movement and/or human trafficking of refugees in the Horn of Africa and on the Central Mediterranean Route. It cooperates with a wide network of Universities, research organisations, civil society and experts from Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Djibouti, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Uganda and across Africa. Key in-depth publications can be accessed on the website. Reported war situation (as confirmed per 11 January) - The former President of Tigray region, Abay Weldu, is arrested by Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF). According to ENDF the arrest was made in a remote valley. Abay Weldu was the President of the Tigray Region from 2010 to 2018. - It was noted that in the TV images Abay Weldu looked very unwell. - Tigray acting Deputy President Dr. Abraham Tekeste is also arrested, Abraham Tekeste was the Minister of Finance and Economic Cooperation (MoFEC) of Ethiopia in 2016; he was MoFEC’s State Minister for four years, and served as Deputy Commissioner to the National Planning Commission of Ethiopia (2015-2016) and Minister of Urban Development Policy Research and Plan Bureau Head of Ethiopia (2005-2010). - Names of other arrests include Dr. Redae Berhe, former chief auditor of the Tigray region; Dr. Muleta Yirga, Director of the Tigray Statistics Agency; Mr. Iqubay Berhe, Head of Religious Affairs in Tigray; Mr. -

Contact Us on [email protected] Dr Mesfin

Appeal to the UN Security Council to Support Ethiopian Sovereignty by Rejecting the TPLF Cyber Warfare Based False Claims. Date: March 10, 2021 The Ethiopian Professional Association in Southern Africa (EthPASA) is a non-governmental, non- profit and independent professionals’ association not affiliated to any religious and/or political organization. EthPASA (https://ethpasa.org) is deeply concerned about the international public relations offensive campaigns that came after the November 4, 2020, military confrontation initiated by the TPLF leadership. TPLF’s regional forces launched a concerted attack on the Ethiopian Federal Defence Forces' Northern Command, which was based in several military bases in Tigray. They confiscated the Command's military equipment, detained thousands of its members, and killed hundreds of them in horrific circumstances. The Ethiopian Federal Government has tried several avenues to resolve the conflict peacefully, and reluctantly joined the war started by the TPLF for no other reason other than to maintain the enforcement of the rule of law. Dr. Abiy said he eagerly likes to send surgical masks to the people of Tigray and not weapons. The federal Government released the budget to Tigray by sending 6 billion Ethiopian Birr the day before TPLF declared the war against the Federal Forces Northern Command stationed to defend the people in the region. The Government cannot be blamed for the war started by the TPLF leadership when they should have negotiated with a number of traditional mediators sent by the federal Government and civil society organisations including religious leaders to promote a peaceful transition after their nearly 30 years divisive rule. -

Education Needs Assessment for Mekelle City, Ethiopia

MCI SOCIAL SECTOR WORKING PAPER SERIES N° 5/2009 EDUCATION NEEDS ASSESSMENT FOR MEKELLE CITY, ETHIOPIA Prepared by Jessica Lopez , Moumié Maoulidi and MCI September 2009 NB: This needs assessment was initially researched and prepared by Jessica Lopez. It was revised and updated by MCI Social Sector Research Manager Moumié Maoulidi who also ran the EPSSIm model simulations and wrote the introduction and the conclusion and recommendations section and revised the EPPSIm results section. MCI intern Michelle Reddy assisted in reviewing and updating the report. The report also benefitted from input provided by MCI Social Sector Specialist in Ethiopia, Aberash Abay. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am most grateful to the Millennium Cities Initiative at Columbia University’s Earth Institute for enabling me to conduct educational research in Ethiopia for six weeks during the summer of 2008. I had a great deal of support from Ms. Aberash Abay, MCI Social Sector Specialist for Mekelle, who provided invaluable information on where and how to gather the information I needed for my work. Ms. Abay also facilitated my entrée into government agencies and my visits with local school administrators and officials. The substantive knowledge, advice and statistical data provided by Mr. Ato Gebremedihn, Head of Statistics at the Tigray Regional Education Bureau, were crucial to the production of this report. Mr. Ato Gebremedihn has continued to provide data and documentation during the last six months, as this report was being written. I would especially like to thank all of the local officials, administrators and teachers who took the time to meet with me and share information.