Education Needs Assessment for Mekelle, Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education in Ethiopia

The Educational System of Ethiopia Liliane Bauduy, Senior Evaluator Educational Credential Evaluators, Inc. International Education Association of South Africa - IEASA 12th Annual Conference 27th – 30th August, 2008 General Facts Ethiopian calendar year - The Ethiopian year consists of 365 days, divided into twelve months of thirty days each plus one additional month of five days (six in leap years). Ethiopian New Year's falls on September 11 and ends the following September 10, according to the Gregorian (Western) calendar. From September 11 to December 31, the Ethiopian year runs seven years behind the Gregorian year; thereafter, the difference is eight years. Hence, the Ethiopian year 1983 began on September 11, 1990, according to the Gregorian calendar, and ended on September 10, 1991. This discrepancy results from differences between the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church as to the date of the creation of the world. Source: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/ethiopia/et_glos.html (Library of Congress) History - In 1974, a military junta, the Derg, deposed Emperor Haile SELASSIE (who had ruled since 1930) and established a socialist state. the regime was finally toppled in 1991 by a coalition of rebel forces, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). A border war with Eritrea late in the 1990's ended with a peace treaty in December 2000. Religions: Christian 60.8% (Orthodox 50.6%, Protestant 10.2%), Muslim 32.8%, traditional 4.6%, other 1.8% (1994 census) Languages: Amarigna 32.7%, Oromigna -

Accessibility Inequality to Basic Education in Amhara Region

Accessibility in equality to Basic Education O.A. A. & Kerebih A. 11 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Accessibility In equality to Basic Education in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. O.A. AJALA (Ph.D.) * Kerebih Asres** ABSTRACT Accessibility to basic educational attainment has been identified as collateral for economic development in the 21st century. It has a fundamental role in moving Africa countries out of its present tragic state of underdevelopment. This article examines the situation of basic educational services in Amhara region of Ethiopia in terms of availability and accessibility at both primary and secondary levels. It revealed that there is a gross inadequacy in the provision of facilities and personnel to adequately prepare the youth for their future, in Amhara region. It also revealed the inequality of accessibility to basic education services among the eleven administrative zones in the region with antecedent impact on the development levels among the zones and the region at large. It thus called for serious intervention in the education sector of the region, if the goal of education for development is to be realized, not only in the region but in the country at large.. KEYWORDS: Accessibility, Basic Education, Development, Inequality, Amhara, Ethiopia _________________________________________________________________ Dept. of Geography Bahir Dar University Bahir Dar, Ethiopia * [email protected] Ethiop. J. Educ. & Sc. Vol. 3 No. 2 March, 2008 12 INTRODUCTION of assessment of educational services provision at primary and secondary schools Accessibility to basic education has been in Ethiopia, taking Amhara National identified as a major indicator of human Regional State as a case study. capital formation of a country or region, which is an important determinant of its The article is arranged into six sections. -

55-68 Impact of Area Enclosures on Density

pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com East African Journal of Sciences (2007) Volume 1 (1) 55-68 Impact of Area Enclosures on Density and Diversity of Large Wild Mammals: The Case of May Ba’ati, Douga Tembien District, Central Tigray, Ethiopia Mastewal Yami1*, Kindeya Gebrehiwot1, M. Stein2, and Wolde Mekuria1 1Department of Land Resources Management and Environmental Protection, Mekelle University, P O Box 231, Mekelle, Ethiopia 2University of Life Sciences, Norway Abstract: In Ethiopian highlands, area enclosures have been established on degraded areas for ecological rehabilitation. However, information on the importance of area enclosures in improving wild fauna richness is lacking. Thus, this study was conducted to assess the impact of enclosures on density and diversity of large wild mammals. Direct observations along fixed width transects with three timings, total counting with two timings, and pellet drop counts were used to determine population of large wild mammals. Regression analysis and ANOVA were used to test the significance of the relationships among age of enclosures, canopy cover, density and diversity of large wild mammals. The enclosures have higher density and diversity of large wild mammals than adjacent unprotected areas. The density and diversity of large wild mammals was higher for the older enclosures with few exceptions. Diversity of woody species also showed strong relationship (r2 = 0.77 and 0.92) with diversity of diurnal and nocturnal wild mammals. Significant relationship (at p<0.05) was observed between age and density as well as among canopy cover, density and diversity of large nocturnal wild mammals. -

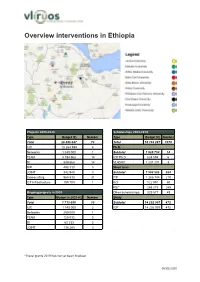

Overview Interventions in Ethiopia

Overview interventions in Ethiopia Projects 2003-2020 Scholarships 2003-2019 Type Budget (€) Number Type Budget (€) Number Total 26 356 647 73 Total 18 103 287 1070 IUC 18 264 999 4 Ph.D. Networks 1 040 000 1 Subtotal 1 825 794 14 TEAM 4 194 968 14 ICP Ph.D. 624 594 6 SI 849 868 14 VLADOC 1 201 201 8 RIP 498 330 5 Short term JOINT 342 940 3 Subtotal 1 984 585 584 Crosscutting 965 833 31 ITP 1 265 744 210 ICT Infrastructure 199 709 1 KOI 122 991 60 REI* 266 273 265 Ongoing projects in 2020 Other scholarships 329 577 49 Type Budget in 2020 (€) Number Study Total 1 713 650 10 Subtotal 14 292 907 472 IUC 1 140 000 2 ICP 14 292 907 472 Networks 250 000 1 TEAM 125 032 2 SI 62 333 2 JOINT 136 285 3 *Travel grants 2019 has not yet been finalised. 06/02/2020 List of projects 2003-2020 Flemish Total Type Runtime Title Local promoter Local institution promoter budget (€) J. Deckers IUC 2003-2014 Institutional University Cooperation with Mekelle University (MU) (phase 1, 2 and phase out) K. Gebrehiwot Mekelle University 6.655.000 (KUL) L. Duchateau IUC 2005-2018 Institutional University Cooperation with Jimma University (JU) (phase 1 and 2, and phase out) K. Tushune Jimma University 6.855.000 (UG) Institutional University Cooperation with Arba Minch University (AMU) (pre-partner programme and IUC 2015-2021 R. Merckx (KUL) G.G. Sulla Arba Minch University 3.000.000 phase 1) Institutional University Cooperation with Bahir Dar University (BDU) (pre-partner programme and IUC 2015-2021 J. -

Ethiopia Digitalization, the Future of Work and the Teaching Profession Project

Background report Digitalization in teaching and education in Ethiopia Digitalization, the future of work and the teaching profession project Moges Yigezu Background report Digitalization in teaching and education in Ethiopia Digitalization, the future of work and the teaching profession project Moges Yigezu With financial support from Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH on behalf of Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). As a federally owned enterprise, GIZ supports the German Government in achieving its objectives in the field of international cooperation for sustainable development. International Labour Office • Geneva ii Copyright © International Labour Organization 2021 First published 2021 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publishing (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concer- ning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. -

Site Report: Kafa Biosphere Reserve and Adjacent Protected Areas

Site report: Kafa Biosphere Reserve and adjacent Protected Areas Part of the NABU / Zoo Leipzig Project ‘Field research and genetic mapping of large carnivores in Ethiopia’ Hans Bauer, Alemayehu Acha, Siraj Hussein and Claudio Sillero-Zubiri Addis Ababa, May 2016 Contents Implementing institutions and contact persons: .......................................................................................... 3 Preamble ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Objective ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Description of the study site ......................................................................................................................... 5 Kafa Biosphere Reserve ............................................................................................................................ 5 Chebera Churchura NP .............................................................................................................................. 5 Omo NP and the adjacent Tama Reserve and Mago NP .......................................................................... 6 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................ -

The Historic Move, Contemporary Challenges and Opportunities in Ethiopian Education

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals International Journal of African and Asian Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2409-6938 An International Peer-reviewed Journal Vol.26, 2016 The Historic Move, Contemporary Challenges and Opportunities in Ethiopian Education Sisay Awgichew Wondemetegegn Lecturer in the Department of Adult Education and Community Development, College of Education and Behavioral Sciences, Haramaya University, Ethiopia Abstract The intention of this manuscript is to overview the development of Ethiopian Education from Early to Modern schooling. Opportunities and challenges regarding education quality and access in Ethiopia are concerned under the study. The researcher used descriptive research design and qualitative research methods. Manuscript review (policy document , researches, historical literatures and different statistics) , focus group discussion with 120 PGDT(Postgraduate Diploma In Secondary School Teaching) student-teachers and summer In-service students and interview conducted with 10 secondary school directors and observation was the viable instrument. The information thematised and analyzed qualitatively through narration and explanation. Recently, Ethiopia score tremendous expansion in primary and secondary as well as Higher Education. However, the fact that a large majority of the Ethiopian population lives in rural areas still lack of equitable access, equity and quality of education, organization of the school system and of the relevance of the curriculum needs revision. The findings disclose that in the last ten years Multi-million children obtain the opportunity to primary and secondary education in Ethiopia. The number of teachers and institution significantly increased. -

The Relevance of Current Ethiopian Primary School Teacher Education Program for Pre-Service Mathematics Teacher's Knowledge An

EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 2021, 17(5), em1964 ISSN:1305-8223 (online) OPEN ACCESS Research Paper https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/10858 The Relevance of Current Ethiopian Primary School Teacher Education Program for Pre-service Mathematics Teacher’s Knowledge and Teacher Educator’s Awareness about Mathematics Knowledge for Teaching Anteneh Tefera 1*, Mulugeta Atnafu 2, Kassa Michael 2 1 Dire Dawa University, ETHIOPIA 2 Addis Ababa University, ETHIOPIA Received 22 September 2020 ▪ Accepted 3 March 2021 Abstract The major objective of this study was to examine the effect of Ethiopian pre-service primary school teacher education program to mathematics teacher’s knowledge and assess teacher educator’s awareness about Mathematics Knowledge for Teaching. The study employed quantitative and qualitative research approaches. It was also used survey and narration research design. The population of this study were all third-year pre-service teacher classes in generalist, specialist and linear modality classes in three sampled colleges of teacher education such as: Kotebe Metropolitan University, Hawassa College of teacher education and Arba Minch college of teacher education. The sampling technique used was purposive sampling. The result showed that program type has no effect on the mean scores between specialist and linear students in Mathematics Knowledge for Teaching scale. Significant difference was not observed in mean score of Mathematics Knowledge for Teaching test against gender. The findings also showed that teacher educators have no enough knowledge/awareness about the term Mathematics Knowledge for Teaching and its components. Thus, the study suggested that successive training should be organized to train teacher educators about Mathematics Knowledge for Teaching and mathematics pedagogies and recent mathematics education theories in general. -

Indigenous Knowledge and Early Childhood Care and Education in Ethiopia

4 Indigenous knowledge and early childhood care and education in Ethiopia Hawani Negussie1 and Charles L. Slater2 1Brandman University, Irvine, CA; 2California State University, Long Beach, CA, USA Abstract The purpose of this research study was to explore the integration of indigenous knowledge and cultural practices in Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) programmes in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Vygotsky's (1986) sociocultural theory in combination with Yosso's (2005) community cultural wealth theory served as the conceptual as well as the methodological framework advising the components of this research. This qualitative case study invited perspectives from local parents, teachers, directors, a university faculty member, and administrative personnel from the Ministry of Education in Ethiopia. Major findings uncovered that language, the Ethiopian alphabet (fidel), traditions and cultural practices passed down from generation to generation, were seen as part of Ethiopia’s larger indigenous knowledge system. The value of using indigenous knowledge, including the extent of integration of cultural practices as measured through use of native language, curriculum and educational philosophy, revealed distinct language preferences (Amharic or English) based on school, personal wants and population demographics. Keywords: Early Childhood Care and Education; indigenous education; multilingual education; Ethiopia; community cultural wealth Introduction There is a great reverence toward Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) in Ethiopia, especially the importance of giving every child the opportunity to go to school at a young age so that their future will yield a more prosperous end. In the last 100 years, Ethiopia has recognized the importance of education as a catalyst to the empowerment and advancement of people and society at large. -

Education Needs Assessment for Mekelle City, Ethiopia

MCI SOCIAL SECTOR WORKING PAPER SERIES N° 5/2009 EDUCATION NEEDS ASSESSMENT FOR MEKELLE CITY, ETHIOPIA Prepared by Jessica Lopez , Moumié Maoulidi and MCI September 2009 NB: This needs assessment was initially researched and prepared by Jessica Lopez. It was revised and updated by MCI Social Sector Research Manager Moumié Maoulidi who also ran the EPSSIm model simulations and wrote the introduction and the conclusion and recommendations section and revised the EPPSIm results section. MCI intern Michelle Reddy assisted in reviewing and updating the report. The report also benefitted from input provided by MCI Social Sector Specialist in Ethiopia, Aberash Abay. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am most grateful to the Millennium Cities Initiative at Columbia University’s Earth Institute for enabling me to conduct educational research in Ethiopia for six weeks during the summer of 2008. I had a great deal of support from Ms. Aberash Abay, MCI Social Sector Specialist for Mekelle, who provided invaluable information on where and how to gather the information I needed for my work. Ms. Abay also facilitated my entrée into government agencies and my visits with local school administrators and officials. The substantive knowledge, advice and statistical data provided by Mr. Ato Gebremedihn, Head of Statistics at the Tigray Regional Education Bureau, were crucial to the production of this report. Mr. Ato Gebremedihn has continued to provide data and documentation during the last six months, as this report was being written. I would especially like to thank all of the local officials, administrators and teachers who took the time to meet with me and share information. -

Referral Systems for Preterm, Low Birth Weight, and Sick Newborns in Ethiopia: a Qualitative Assessment Alula M

Teklu et al. BMC Pediatrics (2020) 20:409 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02311-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Referral systems for preterm, low birth weight, and sick newborns in Ethiopia: a qualitative assessment Alula M. Teklu1, James A. Litch2* , Alemu Tesfahun3, Eskinder Wolka4, Berhe Dessalegn Tuamay5, Hagos Gidey6, Wondimye Ashenafi Cheru7, Kirsten Senturia2, Wendemaghen Gezahegn1 and And the Every Preemie–SCALE Ethiopia Implementation Research Collaboration Group Abstract Background: A responsive and well-functioning newborn referral system is a cornerstone to the continuum of child health care; however, health system and client-related barriers negatively impact the referral system. Due to the complexity and multifaceted nature of newborn referral processes, studies on newborn referral systems have been limited. The objective of this study was to assess the barriers for effective functioning of the referral system for preterm, low birth weight, and sick newborns across the primary health care units in 3 contrasting regions of Ethiopia. Methods: A qualitative assessment using interviews with mothers of preterm, low birth weight, and sick newborns, interviews with facility leaders, and focus group discussions with health care providers was conducted in selected health facilities. Data were coded using an iteratively developed codebook and synthesized using thematic content analysis. Results: Gaps and barriers in the newborn referral system were identified in 3 areas: transport and referral communication; availability of, and adherence to newborn referral protocols; and family reluctance or refusal of newborn referral. Specifically, the most commonly noted barriers in both urban and rural settings were lack of ambulance, uncoordinated referral and return referral communications between providers and between facilities, unavailability or non-adherence to newborn referral protocols, family fear of the unknown, expectation of infant death despite referral, and patient costs related to referral. -

Policy Debate in Ethiopian Teacher Education: Retrospection and Future Direction

International Journal of Progressive Education, Volume 13 Number 3, 2017 © 2017 INASED 61 Policy Debate in Ethiopian Teacher Education: Retrospection and Future Direction Aweke Shishigui Wachemo University Eyasu Gemechuii Wolkite University Kassa Michaeliii Addis Ababa University Mulugeta Atnafuiv Addis Ababa University Yenealem Ayalewv Dire-Dawa University Abstract Though, Ethiopia registered an extraordinary achievement in terms of increasing student enrolment, still quality of education remains a challenge and is becoming a bottleneck. One of the problems might be the structure and nature of teacher education itself. The purpose of this study therefore was to critically examine the existing literature and policy documents and come up with effective as well as valuable modality of teacher education which will be workable in Ethiopian context. In Ethiopia, there are two extreme views that can be taken as challenges for teacher education program: pedagogical knowledge vs. subject matter knowledge. There is also contention on the modality of teacher education: concurrent vs. consecutive. The study show that the greatest ever challenge in teacher education is registered during the Post-TESO period. The program is troubled. Based on the results of this study, imperative implications for practice are forwarded. Key terms: teacher education, concurrent model, consecutive model, driving force, curriculum structure ------------------------------- i Aweke Shishigu Res. Asst., Wachemo University, Ethiopia Correspondence: [email protected] ii Eyasu Gemechu Res. Asst., Wolkite University, Ethiopia iii Kassa Michael Assist. Prof. Dr., Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia iv Mulugeta Atnafu Assoc. Prof. Dr., Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia v Yenealem Ayalew Res. Asst., Dire-Dawa University, Ethiopia International Journal of Progressive Education, Volume 13 Number 3, 2017 © 2017 INASED 62 Introduction In the Ethiopian context, formal schooling is largely organized and controlled by the government.