Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turkey and the Failed Coup One Year Later | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 2835 Turkey and the Failed Coup One Year Later by Omer Taspinar, Soner Cagaptay, James Jeffrey Jul 20, 2017 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Omer Taspinar Omer Taspinar is a professor of national security strategy at the National War College, focusing on the political economy of Europe, the Middle East, and Turkey. Soner Cagaptay Soner Cagaptay is the Beyer Family fellow and director of the Turkish Research Program at The Washington Institute. James Jeffrey Ambassador is a former U.S. special representative for Syria engagement and former U.S. ambassador to Turkey and Iraq; from 2013-2018 he was the Philip Solondz Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute. He currently chairs the Wilson Center’s Middle East Program. Brief Analysis Watch three expert observers examine a divided Turkey one year after the failed military coup of 2016. On July 13, Omer Taspinar, Soner Cagaptay, and James F. Jeffrey addressed a Policy Forum at The Washington Institute. Taspinar is a professor at the National War College and an adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins University's School of Advanced International Studies. Cagaptay is the Beyer Family Fellow and director of the Turkish Research Program at the Institute. Jeffrey is the Institute's Philip Solondz Distinguished Fellow and a former U.S. ambassador to Turkey. The following is a rapporteur's summary of their remarks. OMER TASPINAR W hile the authoritarian trend in Turkish politics is well documented in Washington circles, Fethullah Gulen is still very enigmatic for most Americans (despite his longtime exile in Pennsylvania). Some background on the Gulen movement's marriage of convenience with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's Justice and Development Party (AKP), therefore, provides important context. -

Turkey's Deep State

#1.12 PERSPECTIVES Political analysis and commentary from Turkey FEATURE ARTICLES TURKEY’S DEEP STATE CULTURE INTERNATIONAL POLITICS ECOLOGY AKP’s Cultural Policy: Syria: The Case of the Seasonal Agricultural Arts and Censorship “Arab Spring” Workers in Turkey Pelin Başaran Transforming into the Sidar Çınar Page 28 “Arab Revolution” Page 32 Cengiz Çandar Page 35 TURKEY REPRESENTATION Content Editor’s note 3 ■ Feature articles: Turkey’s Deep State Tracing the Deep State, Ayşegül Sabuktay 4 The Deep State: Forms of Domination, Informal Institutions and Democracy, Mehtap Söyler 8 Ergenekon as an Illusion of Democratization, Ahmet Şık 12 Democratization, revanchism, or..., Aydın Engin 16 The Near Future of Turkey on the Axis of the AKP-Gülen Movement, Ruşen Çakır 18 Counter-Guerilla Becoming the State, the State Becoming the Counter-Guerilla, Ertuğrul Mavioğlu 22 Is the Ergenekon Case an Opportunity or a Handicap? Ali Koç 25 The Dink Murder and State Lies, Nedim Şener 28 ■ Culture Freedom of Expression in the Arts and the Current State of Censorship in Turkey, Pelin Başaran 31 ■ Ecology Solar Energy in Turkey: Challenges and Expectations, Ateş Uğurel 33 A Brief Evaluation of Seasonal Agricultural Workers in Turkey, Sidar Çınar 35 ■ International Politics Syria: The Case of the “Arab Spring” Transforming into the “Arab Revolution”, Cengiz Çandar 38 Turkey/Iran: A Critical Move in the Historical Competition, Mete Çubukçu 41 ■ Democracy 4+4+4: Turning the Education System Upside Down, Aytuğ Şaşmaz 43 “Health Transformation Program” and the 2012 Turkey Health Panorama, Mustafa Sütlaş 46 How Multi-Faceted are the Problems of Freedom of Opinion and Expression in Turkey?, Şanar Yurdatapan 48 Crimes against Humanity and Persistent Resistance against Cruel Policies, Nimet Tanrıkulu 49 ■ News from hbs 53 Heinrich Böll Stiftung – Turkey Representation The Heinrich Böll Stiftung, associated with the German Green Party, is a legally autonomous and intellectually open political foundation. -

The Plot Against the Generals

THE PLOT AGAINST THE GENERALS Dani Rodrik* June 2014 On a drizzly winter day four-and-a-half years ago, my wife and I woke up at our home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to sensational news from our native Turkey. Splashed on the first page of Taraf, a paper followed closely by the country’s intelligentsia and well-known for its anti-military stance, were plans for a military coup as detailed as they were gory, including the bombing of an Istanbul mosque, the false- flag downing of a Turkish military jet, and lists of politicians and journalists to be detained. The paper said it had obtained documents from 2003 which showed a group within the Turkish military had plotted to overthrow the then-newly elected Islamist government. The putative mastermind behind the coup plot was pictured prominently on the front page: General Çetin Doğan, my father-in-law (see picture). General Doğan and hundreds of his alleged collaborators would be subsequently demonized in the media, jailed, tried, and convicted in a landmark trial that captivated the nation and allowed Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to consolidate his power over the secular establishment. In a judgment issued in October 2013, Turkey’s court of appeals would ratify the lower court’s decision and the decades-long prison sentences it had meted out. Today it is widely recognized that the coup plans were in fact forgeries. Forensic experts have determined that the plans published by Taraf and forming the backbone of the prosecution were produced on backdated computers and Cover of Taraf on the alleged coup attempt made to look as if they were prepared in 2003. -

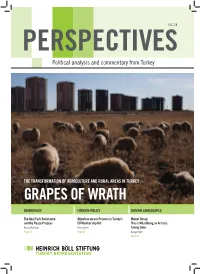

Grapes of Wrath

#6.13 PERSPECTIVES Political analysis and commentary from Turkey THE TRANSFORMATION OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL AREAS IN TURKEY GRAPES OF WRATH DEMOCRACY FOREIGN POLICY HUMAN LANDSCAPES The Gezi Park Resistance Objective versus Process in Turkey’s Memet Aksoy: and the Peace Process EU Membership Bid This is What Being an Artist is: Nazan Üstündağ Erhan İçener Taking Sides Page 54 Page 62 Ayşegül Oğuz Page 66 TURKEY REPRESENTATION Contents From the editor 3 ■ Cover story: The transformation of agriculture and rural areas in Turkey The dynamics of agricultural and rural transformation in post-1980 Turkey Murat Öztürk 4 Europe’s rural policies a la carte: The right choice for Turkey? Gökhan Günaydın 11 The liberalization of Turkish agriculture and the dissolution of small peasantry Abdullah Aysu 14 Agriculture: Strategic documents and reality Ali Ekber Yıldırım 22 Land grabbing Sibel Çaşkurlu 26 A real life “Grapes of Wrath” Metin Özuğurlu 31 ■ Ecology Save the spirit of Belgrade Forest! Ünal Akkemik 35 Child poverty in Turkey: Access to education among children of seasonal workers Ayşe Gündüz Hoşgör 38 Urban contexts of the june days Şerafettin Can Atalay 42 ■ Democracy Is the Ergenekon case a step towards democracy? Orhan Gazi Ertekin 44 Participative democracy and active citizenship Ayhan Bilgen 48 Forcing the doors of perception open Melda Onur 51 The Gezi Park Resistance and the peace process Nazan Üstündağ 54 Marching like Zapatistas Sebahat Tuncel 58 ■ Foreign Policy Objective versus process: Dichotomy in Turkey’s EU membership bid Erhan İcener 62 ■ Culture Rural life in Turkish cinema: A location for innocence Ferit Karahan 64 ■ Human Landscapes from Turkey This is what being an artist is: Taking Sides Memet Aksoy 66 ■ News from HBSD 69 Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Turkey Represantation The Heinrich Böll Stiftung, associated with the German Green Party, is a legally autonomous and intellectually open political foundation. -

TURKEY Human Rights Defenders, Guilty Until Proven Innocent International Fact-Finding Mission Report ˙ I HD ©

TURKEY HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS, GUILTY UNTIL PROVEN INNOCENT International Fact-Finding Mission Report HD ˙ I © May 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 1. Cemal Bektas in his cell 2. Pinar Selek Acronyms ............................................................................................................................... 4 3. Ragıp Zarakolu 4. Executive Summary ...............................................................................................................5 Muharrem Erbey and other activists on December 26, Introduction: objective and methodology of the mission .................................................7 2009 before the hearing that confirmed the charges I. Political context: Recent institutional reforms and policies have against 152 Kurdish figures. so far failed to address Turkey’s authoritarian tendencies ................................................ 9 Contrary to the principle of presumption of innocence, II. Malfunctioning political and judicial systems .................................................................. 15 the media was informed of A. The international legal framework: a good ratification record ................................. 15 the hearing and this photo 1. The protection of freedom of association ................................................................ 15 was broadly published in the 2. The protection of freedom of expression .................................................................. 16 media. B. The domestic legal and institutional framework: a deficient framework ................ -

The Gülen Model

The Gülen Model How Kemalism Liberalized Islam by Paul Sobanski A Distinctly Turkish Islam: the Gülen Movement’s Melds Modernization and Islam A secularist ideology, fiercely defended by the military and Kemalist elite, has been locked in symbiotic conflict with Islamist ideology on a political and social level since the formation of the Republic of Turkey.1 Forged in the pit of this endless tension were the teachings of Turkish Imam Fethullah Gülen2. He preaches a moderate Islam. His teachings promote interfaith dialogue, tolerance, study of math and science, multi-party democracy, and active participation in capitalism. He denounces terrorism, violence, and claims to lack a political agenda.3 The huge network of his followers has become known as the Gülen Movement. Sympathizers of the Movement have shown themselves willing to engage in power struggles at the cost of ideological commitment to democratic rule of law. In a land plagued by political intrigue, this may be a necessary evil on the road to liberalization and democratization. So far, they have been instrumental in the struggle for control of the state, yet have shown less enthusiasm to liberate society from the control of the state—aside from the forces of Islam. The Gülen Movement represents the first potential movement to meld the elements of traditional Islam with modern Western ideals of democracy and freedom. Could it actually be the maturation of the Kemalist’s attempt to foster a discussion oriented, open-minded Muslim with a sense of popular sovereignty? Or does the continuous willingness to provide overwhelmingly support to an increasingly authoritarian toned and eastward oriented prime minister indicate nostalgia for the era of Sultans? While seems there is a risk that the Movement will succumb to the same trappings of absolute state authority that has prevailed in Turkish politics, it also represents the first real possibility of ending the 1 Kemalism is the ideology promulgated by the founder of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal. -

The Unspoken Truth

THE UNSPOKEN TRUTH: DISAPPEARANCES ENFORCED One of the foremost obstacles As the Truth Justice Memory Center, we aim to, in the path of Turkey’s process ■ Carry out documentation work of democratization is the fact regarding human rights violations that have taken place in the past, to publish THE UNSPOKEN that systematic and widespread and disseminate the data obtained, and to demand the acknowledgement human rights violations are of these violations; not held to account, and ■ Form archives and databases for the use of various sections of society; victims of unjust treatments TRUTH: ■ Follow court cases where crimes are not acknowledged and against humanity are brought to trial and to carry out analyses and develop compensated. Truth Justice proposals to end the impunity of public officials; Memory Center contributes ■ Contribute to society learning ENFORCED to the construction of a the truths about systematic and widespread human rights violations, democratic, just and peaceful and their reasons and outcomes; and to the adoption of a “Never present day society by Again” attitude, by establishing a link between these violations and the supporting the exposure of present day; DISAPPEAR- systematic and widespread ■ Support the work of civil society organizations that continue to work human rights violations on human rights violations that have taken place in the past, and reinforce that took place in the past the communication and collaboration between these organizations; with documentary evidence, ANCES ■ Share experiences formed in the reinforcement of social different parts of the world regarding transitional justice mechanisms, and ÖZGÜR SEVGİ GÖRAL memory, and the improvement initiate debates on Turkey’s transition period. -

Democracy in Crisis: Corruption, Media, and Power in Turkey

A Freedom House Special Report Democracy in Crisis: Corruption, Media, and Power in Turkey Susan Corke Andrew Finkel David J. Kramer Carla Anne Robbins Nate Schenkkan Executive Summary 1 Cover: Mustafa Ozer AFP / GettyImages Introduction 3 The Media Sector in Turkey 5 Historical Development 5 The Media in Crisis 8 How a History Magazine Fell Victim 10 to Self-Censorship Media Ownership and Dependency 12 Imprisonment and Detention 14 Prognosis 15 Recommendations 16 Turkey 16 European Union 17 United States 17 About the Authors Susan Corke is Andrew Finkel David J. Kramer Carla Anne Robbins Nate Schenkkan director for Eurasia is a journalist based is president of Freedom is clinical professor is a program officer programs at Freedom in Turkey since 1989, House. Prior to joining of national security at Freedom House, House. Ms. Corke contributing regularly Freedom House in studies at Baruch covering Central spent seven years at to The Daily Telegraph, 2010, he was a Senior College/CUNY’s School Asia and Turkey. the State Department, The Times, The Transatlantic Fellow at of Public Affairs and He previously worked including as Deputy Economist, TIME, the German Marshall an adjunct senior as a journalist Director for European and CNN. He has also Fund of the United States. fellow at the Council in Kazakhstan and Affairs in the Bureau written for Sabah, Mr. Kramer served as on Foreign Relations. Kyrgyzstan and of Democracy, Human Milliyet, and Taraf and Assistant Secretary of She was deputy editorial studied at Ankara Rights, and Labor. appears frequently on State for Democracy, page editor at University as a Critical Turkish television. -

Ergenekon: an Illegitimate Form of Government

COMMENTARY ERGENEKON: AN ILLEGITIMATE FORM OF GOVERNMENT Ergenekon: An Illegitimate Form of Government MARKAR ESAYAN* ABSTRACT On August 5th, 2013, an Istanbul court reached its verdict in the Ergenekon coup plot trial, handing down various prison sentences to 247 defendants, including the former Chief of Mili- tary Staff and several high-ranking members of the military’s com- mand. Although the Supreme Court of Appeals has yet to make a final decision on the 6-year legal battle, the Ergenekon trial has al- ready become part of the country’s history as a sign that anti-dem- ocratic forces, many of whom date back to the final years of the Ottoman Empire, no longer have free reign. Notwithstanding its limited scope and other shortcomings, the court’s decision marks but a humble beginning for Turkey’s acknowledgement of the dark chapters in its history, as well as a challenging struggle to replace the laws of rulers with the rule of law. he Ergenekon coup plot trial, ditional two defendants were “leaders the first serious judicial inqui- of a terrorist organization” as 32 de- Try of Turkey’s long tradition of fendants were sentenced for “plotting military coups and ‘deep state’ activ- to overthrow the government.” While ities, reached an end on August 5th, 21 out of 275 defendants were acquit- 2013. Istanbul’s 13th High Criminal ted of all charges, the Court post- Court reached its final verdict (whose poned its verdict on four fugitives. short form consisted of 503 pages) Another three defendants have lost following over 600 hearings, about a their lives over the course of hearings. -

Turkey's Democracy Under Challenge Hearing

TURKEY’S DEMOCRACY UNDER CHALLENGE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON EUROPE, EURASIA, AND EMERGING THREATS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 5, 2017 Serial No. 115–15 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 24–917PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:24 May 03, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 Z:\WORK\_EEET\040517\24917 SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey JOE WILSON, South Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas KAREN BASS, California DARRELL E. ISSA, California WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina AMI BERA, California MO BROOKS, Alabama LOIS FRANKEL, Florida PAUL COOK, California TULSI GABBARD, Hawaii SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas RON DESANTIS, Florida ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina BRENDAN F. BOYLE, Pennsylvania TED S. YOHO, Florida DINA TITUS, Nevada ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois NORMA J. -

Middle East Brief 94 (Brandeis University, 16 Ayşe Buğra and Çağlar Keyder, “The Turkish Welfare Crown Center for Middle East Studies, July 2015)

Crown Family Director Professor of the Practice in Politics Gary Samore Director for Research Charles (Corky) Goodman Professor Proactive Policing, Crime Prevention, and of Middle East History Naghmeh Sohrabi State Surveillance in Turkey Associate Director Kristina Cherniahivsky Hayal Akarsu Associate Director for Research David Siddhartha Patel n early 2000, two years before the governing Justice and Development Party (AKP according to its Turkish Myra and Robert Kraft Professor I of Arab Politics acronym) was elected to power, the Human Rights Inquiry Eva Bellin Commission of the Turkish Grand National Assembly raided Founding Director Professor of Politics police stations in Istanbul to uncover possible human rights Shai Feldman violations. This occurred just after the European Union (EU) Henry J. Leir Professor of the recognized Turkey’s status as a candidate for membership Economics of the Middle East Nader Habibi in December 1999. The Commission found “torture objects,” Renée and Lester Crown Professor such as beams used for so-called “Palestinian hangings” (also of Modern Middle East Studies known as strappado)1 in most of the police stations they visited Pascal Menoret and conducted follow-up visits to some stations a few months Founding Senior Fellows Abdel Monem Said Aly later and interviewed detainees. One was a drug dealer who Khalil Shikaki had been in that particular station several times and had been Sabbatical Fellows tortured each time except this last one; the station personnel Orkideh Behrouzan Gkçe Gnel were probably on their guard after the Commission’s first Harold Grinspoon Junior Research Fellow visit. “Do you know the reason for this change?” asked the Maryam Alemzadeh president of the Commission, Sema Pişkinst (then a member Neubauer Junior Research Fellow of parliament from the Democratic Left Party), who drafted Yazan Doughan the report of these visits. -

Tayip Erdoğan the Lonely Levantine Padisha of the Middle East

RESEARCH PAPER No. 163 AUGUST-SEPTEMBER 2013 TAYIP ERDOGAN THE LONELY LEVANTINE PADISHA OF THE MIDDLE EAST NICKOLAOS MAVROMATES (Security Analyst, RIEAS Research Associate based in USA) ISSN: 2241-6358 Devoted to the memory of Prof. Neoklis Sarris (1940-2011) RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR EUROPEAN AND AMERICAN STUDIES (RIEAS) # 1, Kalavryton Street, Alimos, Athens, 17456, Greece RIEAS: http://www.rieas.gr 1 RIEAS MISSION STATEMENT Objective The objective of the Research Institute for European and American Studies (RIEAS) is to promote the understanding of international affairs. Special attention is devoted to transatlantic relations, intelligence studies and terrorism, European integration, international security, Balkan and Mediterranean studies, Russian foreign policy as well as policy making on national and international markets. Activities The Research Institute for European and American Studies seeks to achieve this objective through research, by publishing its research papers on international politics and intelligence studies, organizing seminars, as well as providing analyses via its web site. The Institute maintains a library and documentation center. RIEAS is an institute with an international focus. Young analysts, journalists, military personnel as well as academicians are frequently invited to give lectures and to take part in seminars. RIEAS maintains regular contact with other major research institutes throughout Europe and the United States and, together with similar institutes in Western Europe, Middle East, Russia and Southeast Asia. Status The Research Institute for European and American Studies is a non-profit research institute established under Greek law. RIEAS’s budget is generated by membership subscriptions, donations from individuals and foundations, as well as from various research projects.