SOCIAL WELL-BEING and ENVIRONMENTAL STRUCTURE of VILUGES in MEERUT DISTRICT Mnittt of S^^Iloiop^P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O.I.H. Government of India Ministry of Housing & Urban Affairs Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 3376 to Be Answered On

O.I.H. GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HOUSING & URBAN AFFAIRS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 3376 TO BE ANSWERED ON JANUARY 01, 2019 SLUMS IN U.P. No. 3376. SHRI BHOLA SINGH: Will the Minister of HOUSING AND URBAN AFFAIRS be pleased to state: (a) whether slums have been identified in the State of Uttar Pradesh, as per 2011 census; (b) if so, the details thereof, location-wise; and (c) the number of people living in the said slums? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) OF THE MINISTRY OF HOUSING & URBAN AFFAIRS [SHRI HARDEEP SINGH PURI] **** (a) to (c): As per the Census-2011, number of slum households was 10,66,363 and slum population was 62,39,965 in the State of Uttar Pradesh. City-wise number of slum households and slum population in the State of Uttar Pradesh are at Annexure. ****** Annexure referred in reply to LSUQ No. 3376 due for 1.1.2018 City -wise number of Slum Households and Slum Population in the State of Uttar Pradesh as per Census 2011 Sl. Town No. of Slum Total Slum Area Name No. Code Households Population 1 120227 Noida (CT) 11510 49407 2 800630 Saharanpur (M Corp.) 12308 67303 3 800633 Nakur (NPP) 1579 9670 4 800634 Ambehta (NP) 806 5153 5 800635 Gangoh (NPP) 1277 7957 6 800637 Deoband (NPP) 4759 30737 7 800638 Nanauta (NP) 1917 10914 8 800639 Rampur Maniharan (NP) 3519 21000 9 800642 Kairana (NPP) 1731 11134 10 800643 Kandhla (NPP) 633 4128 11 800670 Afzalgarh (NPP) 75 498 12 800672 Dhampur (NPP) 748 3509 13 800678 Thakurdwara (NPP) 2857 18905 14 800680 Umri Kalan (NP) 549 3148 15 800681 Bhojpur Dharampur -

District Population Statistics, 4-Meerut, Uttar Pradesh

I Census of India, 195 1 DISTRICT POPULATION STATISTICS UTTAR PRADESH 4-MEEl{UT DISTRICT 315.42 ALLAHABAD: TING AND STATIONERY, UTTAR PRADESH, INDIA 1951 1952 MEE DPS Price, Re.1-S. FOREWORD THE Uttar Pradesh Government asked me in March. 1952, (0 'supply them for the purposes of elections to local bodies population statistics with ,separation for scheduled castes (i) mohalla/ward-wise for urban areas, and (ii) village-wise for rural areas. The Census Tabulation Plan did nbt provide for sorting of scheduled cast<;s population for areas smaller than a tehsil or urban tract and the request from the Uttar Pradesh Government came when the slip sorting had been finished and (he Tabulation Offices closed. As the census slips are mixed up for the purposes of sorting in one lot for a tehsil or urban tract, collection of data regarding scheduled castes population by moh'allas/wards and villages would have involved enormous labour and expense if sorting of the slips had been taken up afresh. Fortunately, however, a secondary census record, viz. the National Citizens' Register, in which each slip has been copied, was available. By singular foresight it had been pre pared mohalla/ward-wise for urban areas and village-wise for rural areas. Th e required information has, therefore. been extracted from. this record, 2. In the above circumstances there is a slight difference in the figures of population as arrived at by an earlier sorting of the slips and as now determined by counting from the National Citizens' Register. This difference has been accen mated by an order passed by me during the later coum from the National Register of Citizens as follows:- (i) Count Ahirwars of Farrukhabad District, Raidas and Bhagar as ·Chamars'. -

List of Class Wise Ulbs of Uttar Pradesh

List of Class wise ULBs of Uttar Pradesh Classification Nos. Name of Town I Class 50 Moradabad, Meerut, Ghazia bad, Aligarh, Agra, Bareilly , Lucknow , Kanpur , Jhansi, Allahabad , (100,000 & above Population) Gorakhpur & Varanasi (all Nagar Nigam) Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Sambhal, Chandausi, Rampur, Amroha, Hapur, Modinagar, Loni, Bulandshahr , Hathras, Mathura, Firozabad, Etah, Badaun, Pilibhit, Shahjahanpur, Lakhimpur, Sitapur, Hardoi , Unnao, Raebareli, Farrukkhabad, Etawah, Orai, Lalitpur, Banda, Fatehpur, Faizabad, Sultanpur, Bahraich, Gonda, Basti , Deoria, Maunath Bhanjan, Ballia, Jaunpur & Mirzapur (all Nagar Palika Parishad) II Class 56 Deoband, Gangoh, Shamli, Kairana, Khatauli, Kiratpur, Chandpur, Najibabad, Bijnor, Nagina, Sherkot, (50,000 - 99,999 Population) Hasanpur, Mawana, Baraut, Muradnagar, Pilkhuwa, Dadri, Sikandrabad, Jahangirabad, Khurja, Vrindavan, Sikohabad,Tundla, Kasganj, Mainpuri, Sahaswan, Ujhani, Beheri, Faridpur, Bisalpur, Tilhar, Gola Gokarannath, Laharpur, Shahabad, Gangaghat, Kannauj, Chhibramau, Auraiya, Konch, Jalaun, Mauranipur, Rath, Mahoba, Pratapgarh, Nawabganj, Tanda, Nanpara, Balrampur, Mubarakpur, Azamgarh, Ghazipur, Mughalsarai & Bhadohi (all Nagar Palika Parishad) Obra, Renukoot & Pipri (all Nagar Panchayat) III Class 167 Nakur, Kandhla, Afzalgarh, Seohara, Dhampur, Nehtaur, Noorpur, Thakurdwara, Bilari, Bahjoi, Tanda, Bilaspur, (20,000 - 49,999 Population) Suar, Milak, Bachhraon, Dhanaura, Sardhana, Bagpat, Garmukteshwer, Anupshahar, Gulathi, Siana, Dibai, Shikarpur, Atrauli, Khair, Sikandra -

Future of Settlement On

MAP ---- WATER TREATMENT PLANTS- DELHI ---- FUTURE SOURCES OF RAW WATER FOR DELHI CONTENTS ---- SEWAGE TREATMENT PLANTS- DELHI ---- DRAINAGE SYSTEM IN DELHI Modified Planning & Implementation of NCR: ---- LANDFILL SITES - DELHI ---- NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION PROPOSED SETTLEMENT ---- STRATEGY FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF POWER PATTERN 2021 SECTOR 1. INITIAL PLANNING OF NOIDA. ---- LIST OF PROPOSED POLICY BOXES 2. POWERS OF SOME OF THE SECTIONS OF NCR ACT ---- NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION REGIONAL -2001 : ONLY IN BRIEF CONSTITUENT AREAS 3. WHAT TO DO? ---- NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION REGIONAL -2021 : 4. COMPREHENSIVE PLANNING WILL INCLUDE THE CONSTITUENT AREAS FOLLOWING ACTIVITIES: (104 ITEMS) + SOME ITEMS ---- NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION PHYSIOGRAPHY AND MORE SLOPE 5. SOME IMPORTANT POLICY DECISIONS. ---- NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION LITHOLOGY ---- PHYSICAL GROWTH OF DELHI 1803-1959 & SEVEN- SEVENTEEN DELHIS ---- NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION GEOMORPHIC 6. NAMES OF NCR CITIES/TOWNS FOR THE YEAR 2011 AND ---- NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION GROUND WATER 2021 PROSPECTS I. Haryana ---- POLICY ZONES II. Rajasthan ---- EXISTING SETTLEMENT PATTERN 2001 III. Uttar Pradesh ---- EXISTING TRANSPORT NETWORK (Roads) 2002 7. PROJECTED POPULATION OF NCR CITIES / TOWNS FOR ---- EXISTING TRANSPORT NETWORK (Rail) 2002 THE YEAR 2031 ---- PROPOSED TRANSPORT NETWORK (ROADS) 2021 I. Haryana ---- PROPOSED TRANSPORT NETWORK (RAIL) 2021 II. Rajasthan ---- GROUND WATER RECHARGEABLE AREAS III. Uttar Pradesh ---- MASTER PLAN FOR NOIDA - 2021 ---- MASTER PLAN FOR GREATER NOIDA - 2021 MODIFIED PLANNING & IMPLEMENTATION OF: NCR 1. PRESENT AREA = 30242 SQ.KM. 2. PROPOSED AREA BY 2031 = ___SQ.KM. AFTER ADDING NEW DISTRICTS. 3. PRESENT POPULATION (2017) = ___ M UPS CAMPUS BLOCK-A, PREET VIHAR, 4. PREDICTED POPULATION (2031) = ___ M DELHI-92 (M) 09811018374 E-mail: [email protected] R.G.GUPTA www.rgplan.org, www.rgedu.org, www.uict.org City/Policy Planner NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION TO PREPARATION, ENFORCEMENT AND 5. -

MEERUT: 111111111111'1111111111111111111111111111 Gfpe-PUNE-017942 a GAZETTEER

Dhauanjayarao Gadgii LibRaRy MEERUT: 111111111111'1111111111111111111111111111 GfPE-PUNE-017942 A GAZETTEER, llEING VOLUME IV OF THE DISTRICT GAZETTEERS OF THE UNITEll PROVINCES OF AGRA AND OUDH. COMPILED A.ND EDITED :BY H. R. N E V ILL, 1. C. S. ALLAHABAD: PRINTED :BY F. LUKER, SUl/DT., GOVT. PRESS, UNiTED PnOTINCES. 1904. Price Rs. 3 (48.). GAZETTEER OF MEERU~i .CONTENTS.,. PAGE, .,~AGE, Occupp.tions ••• 101 Boundaries and Area 1 Villages and houses , . 102 Topography ... 2 Contlition of the people 105 },akes · . .. 18 Proprietor~· ••• . ., 107 Tenants; ... , 108 Waste lands •· · ... ', 1' ... 19 ... Groves 21 Rents . ... 109 Minerals ~··... 22 Language and Literature •• , 109 }'auna 24 Edu<(ation : .. , ... 110 Cattle 26 ~· Climate and Rainfall 29 CRAPTEB IV. Medical Aspects ... ... 31 District Sta:ff ... J.I5 CH!PT~]I1I• . Garrison ... 116' Subdivisions 116 Cultivation .. •.. 35 .... Fiscal History ' ... 119 ~oils .. .... 37'' Police' 136 Harvests · ;.. ••.•. 38 Crime 138 Crops .: •. •··· 3~ ,Jail' , '. ·140 .., .. 47 .. l~ri~atiol\ and Cana~s. ~- '·"' 140 .... 57• :Excise ..•. ... }amines ., ·•'• .~ Registratj.on .... ~· .... 142 J>rices andWag~8' .~ •. ·::..~·· 60 .Stamps .. ... ·Ha:. Trade .. • , .. ..... 61 lncome-tax . ' 143 }'airs . •.. .. .... 63 Post-offi!leS . '143 Weights and Mej;\sures 63 Municipalities ... ']44. ]nterest · ·: ~ :' :.,: l.. 64 Act XX towns ... ' ... 145 Manufactures ;,,.' .• · · ":· 65 District Board· ... ... 145 <:ommunicati~n{ .".:... ·:.· :·: ;1 ... 67 _l)i s pensarie s ••• 141i . ... C:S:Al'TEB ·ll[ ' ' ·. CriPTER V. ; '75 Population •. ·.. ~-.~~ r~'. '·•·•"' ~l'l. • ··41 . '147 .. , . 78. Uis~ory ··~... ...... '• , ... 78 -~ J~,·li:;-ions- · ' ... ,, 79 ~ 187 (.'bri~~ianity __:' . ~. ~ . Directory ... ... ,....._...:... '"· Arya Sam~j . · .... ' ,,, 82;. <'' .hins .... .... .,, 82 Appen<U~ ... ·t. .. ·i-ilviii .. I • ,...___ ?\I u sal uia D.~ : ... ..... 83 lliuJue ... ... 88 Index~ ••• ,.... i...;.vii PREFACE. -

2018083185.Pdf

tuin esa losZ{k.kksaijkUr fujfJr efgyk isa'ku ;kstuk ds efgykvksa dh lwpuk viyksM fd;s tkus dk izk:i%& vvv kkk Js.kh ¼v0tk0 bbb dz0 xzke iapk;r dk fodkl [k.M dk tuin dk Z-Z- vkosfndk dk uke ifr dk uke v0t0tk0@f Z-Z- la0la0la0 uke uke uke ,,, iNM+k½ QQQ --- lll S 1 SUMAN MEWARAM 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC B P 2 SHEELA MUNNALAL 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U N 3 MAYA DEVI HARI SINGH 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT - T P 4 BABITA VIRENDRA 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U P 5 SHAKUNTALA PREETAM SINGH 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U P 6 SHIMLA JAIBHAGWAN 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U P 7 LAKHMEERI MADAN PAL 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U P 8 KIRAN CHAMAN LAL 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U S 9 SANTOS PAPPU SINGH 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT SC B P 10 SHOBHA DEVI MOOLCHAND 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U P 11 KISHNO KAILASH 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U 12 MADHU BHAGWAN DAS 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC - U 13 KAUSHALYA MUNNA LAL 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC B P 14 RAMMI NEEPAK 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U S 15 SHANTI DEVI ARVIND KUMAR 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC B P 16 KAMLESH RAMCHANDRA SAINI 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U P 17 GYANWATI DULICHAND 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT OBC U P 18 BALA DEVI SURESH KUMAR 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT - U B 19 MURTI BAUDH SHYAM SINGH 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT SC K B 20 JAIWATI MANGEY RAM 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT SC K P 21 ASHA SUBHASH CHAND 9 KASAMPUR MEERUT (n.n) MEERUT SC U P 22 BALESHWARI GIRIRAJ SINGH -

A Study on Sanitation System of Meerut-U.P. India

Research Journal of Chemical and Environmental Sciences Res. J. Chem. Env. Sci., Volume 1 Issue 5 December 2013: 56-70 Online ISSN 2321-1040 CODEN: RJCEA2 [CAS, USA] Available Online http://www.aelsindia.com ©2013 AELS, India ORIGINAL ARTICLE A Study on Sanitation System of Meerut-U.P. India Rajesh Kumar jain Bharat Group of Colleges,Punjab ABSTRACT Meerut is the 63rd fastest-growing urban area in the world and ranked 242 in 2010 in the list of largest cities and urban areas in the world and second largest city in the National Capital Region of India(NCR) , the 16th largest metropolitan area and 25th largest city in India situated between Ganga and Jamuna, close to the imperial capital. Only 51.3% of people with portable water connections in poor neighbourhoods get above 80% of their total water requirements. 32.5% said they receive water between 60-80% of their demand, while 12.8 get just 50% of their demand. The analysis of other sources of water for 49.8% without access to portable water connection in poor neighbourhoods and the majority, 93% buy water from neighbours or municipal corporation water (stand pipes) at afixed price . Only 1% of those without access said they fetch water from bore-holes or a well near the house. The 2/3 city does not have sewer lines and Municipal corporation does not have any sewer treatment plant. .Drainage system is not there but on record,104 colonies have the same. Modernized mixture approach brings together the best elements from both centralized sanitation and decentralised systems in a number of options and strategies, adapted to the particular infrastructural, institutional, economic and environmental context. -

Nekton Vle's Details

S.R.No. VLE / SCO Name Father's/Husband Name Pin Code Ward No Block Tehseel Complete Address 1 PRABHAT SHARMA SURESH CHAND SHARMA 250404 NAGAR PANCHAYAT-BEHSUMA Hastinapur Mawana Yash Telecom Opp-Behsuma Police Station Bijnore Road Meerut 2 MOHIT SHARMA SATYAVEER SHARMA 250404 NAGAR PANCHAYAT-HASTINAPUR HASTINAPUR MAWANA B-28 J BLOCK HASTINAPUR MEERUT 3 MOHD. SALMAN MOHD.ASLAM 250104 3 MACHHRA MAWANA VINAY PHOTO STUDIO KE SAMNE KITHORE ROAD MAWANA MEERUT 4 MOHD.FAIZAN MOHD.IRFAN 250401 NAGAR PALIKA-01 MAWANA MAWANA MAWANA TEHSEEL ROAD MAWANA MEERUT 5 VINEET KUMAR SHYAM AVTAR 250401 NAGAR PALIKA-03 MAWANA MAWANA MAWANA 996 MUNNALAL MAWANA MEERUT 6 UFAK REHMAN HANIF UR REHMAN 250401 NAGAR PANCHAYAT-PHALAUDA MAWANA MAWANA BUS STAND PHALAWADA MEERUT 7 VANDNA SARVESH MALIK 250406 NAGAR PANCHAYAT- PARIKSHITGARH PARIKSHITGARH MAWANA STUDENT POINT BEHLOLPUR ROAD PARIKSHITGARH MRT. 8 AJAY SHAKTI YADAV GULFAM SINGH YADAV 250002 64 MEERUT MEEERUT 9/1 SWAMI PARA NAEEN BAZAR BUDHANA GATE MEERUT 9 SAMAR AHMAD GULFAM 250501 NAGAR PANCHAYAT- SIWALKHAS JANI MEERUT NAGAR PANCHAYAT SIWALKHAS MEERUT 10 MOHD.ASIF MOHD.ASLAM 245205 NAGAR PANCHAYAT- KHARKHAUDA KHARKHODA MEERUT SAINI MARKET KHARKHODA MEERUT 11 SANJAY KUMAR OMPRAKASH PAL 250401 NAGAR PALIKA-02 MAWANA MAWANA MEERUT HIRALAL MAWANA NEAR TEHSEEL MAWANA MEERUT 12 DHEERENDRA PITAM SINGH 250002 3 MEERUT MEERUT 920 SHAKTI NAGAR MALIYANA MEERUT 13 SAVITA RANI CHANDER SINGH 250002 7 MEERUT MEERUT 102 NOOR NAGAR LISARI ROAD MEERUT 14 ANKIT DHAKA ROHTASH SINGH 250001 9 MEERUT MEERUT TEJ VIHAR LAL GATE ROHTA -

Draft Electoral Roll

DRAFT ELECTORAL ROLL - 2019 STATE - (S24) UTTAR PRADESH No., Name and Reservation Status of Assembly Constituency: 44-Sardhana(GEN) Last Part No., Name and Reservation Status of Parliamentary Service Constituency in which the Assembly Constituency is located: 3-Muzaffarnagar(GEN) Electors 1. DETAILS OF REVISION Year of Revision : 2018 Type of Revision : Summary Revision Qualifying Date :01/01/2019 Date of Draft Publication: 01/09/2018 2. SUMMARY OF SERVICE ELECTORS A) NUMBER OF ELECTORS 1. Classified by Type of Service Name of Service No. of Electors Members Wives Total A) Defence Services 1403 26 1429 B) Armed Police Force 0 0 0 C) Foreign Service 2 0 2 Total in Part (A+B+C) 1405 26 1431 2. Classified by Type of Roll Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Members Wives Total I Original Mother Roll, De-novo(2017), Special 1405 26 1431 2019 Summary Revision 2018 & continuous updation there after Net Electors in the Roll 1405 26 1431 Elector Type: M = Member, W = Wife Page 1 Draft Electoral Roll, 2018 of Assembly Constituency 44-Sardhana (GEN), (S24) UTTAR PRADESH A . Defence Services Sl.No Name of Elector Elector Rank Husband's Regimental Address for House Address Type Sl.No. despatch of Ballot Paper (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) Assam Rifles 1 AMBRISH KUMAR M Rifleman Headquarters Directorate General KHERA SARDHANA Assam Rifles, Record Branch, SARDHANA KHERA Laitumkhrah,Shillong-793011 000000 SARDHANA 2 SOVEER SINGH M Rifleman Headquarters Directorate General DABATHWA Assam Rifles, Record Branch, SARDHANA SARDHANA Laitumkhrah,Shillong-793011 -

MEERUT(GEN) Last Part No., Name and Reservation Status of Parliamentary Service Constituency in Which the Assembly Constituency Is Located: 10-Meerut(GEN) Electors

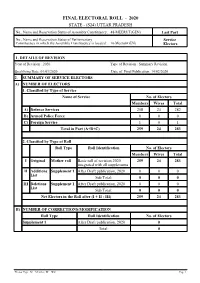

FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL - 2020 STATE - (S24) UTTAR PRADESH No., Name and Reservation Status of Assembly Constituency: 48-MEERUT(GEN) Last Part No., Name and Reservation Status of Parliamentary Service Constituency in which the Assembly Constituency is located: 10-Meerut(GEN) Electors 1. DETAILS OF REVISION Year of Revision : 2020 Type of Revision : Summary Revision Qualifying Date :01/01/2020 Date of Final Publication: 14/02/2020 2. SUMMARY OF SERVICE ELECTORS A) NUMBER OF ELECTORS 1. Classified by Type of Service Name of Service No. of Electors Members Wives Total A) Defence Services 258 24 282 B) Armed Police Force 0 0 0 C) Foreign Service 1 0 1 Total in Part (A+B+C) 259 24 283 2. Classified by Type of Roll Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Members Wives Total I Original Mother roll Basic roll of revision 2020 259 24 283 integrated with all supplements II Additions Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2020 0 0 0 List Sub Total: 0 0 0 III Deletions Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2020 0 0 0 List Sub Total: 0 0 0 Net Electors in the Roll after (I + II - III) 259 24 283 B) NUMBER OF CORRECTIONS/MODIFICATION Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2020 0 Total: 0 Elector Type: M = Member, W = Wife Page 1 Final Electoral Roll, 2020 of Assembly Constituency 48-MEERUT (GEN), (S24) UTTAR PRADESH A . Defence Services Sl.No Name of Elector Elector Rank Husband's Address of Record House Address Type Sl.No. Officer/Commanding Officer for despatch of Ballot Paper (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) -

Spotlaw 2014

Abdul Rehman and Others Vs State Transport Appellate Tribunal and Others Civil Appeal No. 1276 of 1975 Rahimuddin Vs Regional Transport Authority and Others Civil No. 1852 of 1976 (Jaswant Singh, V. R. Krishna Iyer JJ) 08.03.1978 JUDGMENT JASWANT SINGH, J.- 1. This appeal by special leave is directed against the judgment and order dated August 27, 1975 of a Division Bench of the High Court of Judicature at Allahabad in Special Appeal 208 of 1973 upholding the order dated August 28, 1973 of a single Judge of that Court whereby he quashed the order dated May 5, 1973 of the State Transport Appellate Tribunal granting regular permits in favour of the appellants for amalgamated route known as Meerut-Mawana-Miranpur, Meerut-Bijnor via Mawana-Meerut-Mawana Khurd-Phalauda, Meerut-Masuri-Lawar-Phalauda, Meerut-Masuri- Lawar, and Khatauli Phalauda-Mawana-Makdoompur route. 2. The dispute as stated in the judgment and order under appeal relates to Meerut-Mawana-Miranpur route, the limit of the number of stage carriage permits whereof was raised from 11 to 15 in 1959. Out of the additional four permits which thus became available for grant, the Regional Transport Authority granted three to the displaced persons and invited applications to fill up the remaining one vacancy. In response to the invitation, the appellants also applied for grant of the stage carriage permits for the said route. While considering the applications the exercising its authority of grant of the permits under Section 48 read with section 57 of the Motor Vehicles Act, 1939 (here-inafter called 'the Act'), the Regional Transport Authority modified the limit of number of the stage carriage permits and increased it from 15 to 20 which it could not do in view of the law settled by this Court in Abdul Mateen v. -

2018080748.Pdf

tuin esa losZ{k.kksaijkUr o`)koLFkk@fdlku isa'ku ;kstuk ds vkosndksa dh lwph Ø0la0 rglhy fodkl xzke xkao eksgYyk vkosnd dk uke firk@ifr dk fyax Js.kh tUefrfFk vk;q vk/kkj dkMZ cSad@'kk[kk dk uke [kkrk la[;k ch0ih0,y okf"kZd fdlh vU; dk uke [k.M@uxj iapk;r@uxj uke la[;k Øekad@vk vk; isa'ku ;kstuk {ks= dk uke okMZ dk uke ; çek.k dk ykHk rks i= Øekad ugh çkIr gks jgk gSA 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 1 MAWANA MAWANA SANOTA SANOTA SAIDA MO. SIDA MALE MINORITY 60 691192905023 SYNDICATE BANK, 11616739507 - - N SYNB0003070 2 MAWANA MAWANA SANOTA SANOTA OMWATI MAHENDRA FEMALE SC 60 545815664567 SYNDICATE BANK, 98632200024634 - - N SYNB0009863 3 MAWANA MAWANA SANOTA SANOTA ANISHA YUSUF FEMALE MINORITY 65 867613289189 SYNDICATE BANK, 85642200107224 - - N SYNB0008564 4 MAWANA MAWANA SANOTA SANOTA DHARAMPAL MUNSHI FEMALE OBC 65 502657899680 SYNDICATE BANK, 85642210046485 - - N SYNB0008564 5 MAWANA MAWANA BEHJADKA BEHJADKA PREMWATI BISHANPAL SINGH FEMALE OBC 01-01-1956 62 234651845929 SYNDICATE BANK, 8938817237 - - N SYNB0009863 6 MAWANA MAWANA BEHJADKA BEHJADKA RAJVIR MWASI MALE OBC 01-01-1953 65 524172189848 SYNDICATE BANK, 98632200012358 - 40000 N SYNB0009863 7 MAWANA MAWANA NAGLA HAREROO NAGLA HAREROO RAJIYA KHATOON ASAD ALI FEMALE MINORITY, 01-01-1955 63 - PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK, 0317001700031715 - - N GENERAL MAWANA, PUNB0031699 8 MAWANA MAWANA NAGLA HAREROO NAGLA HAREROO KAMLESH KELU RAM FEMALE SC 02-06-1954 64 984367549491 PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK, 0317001700007958 - 42000 N MAWANA, PUNB0031700 9 MAWANA MAWANA BANA BANA OMWATI RANVEER