The Kinesthetic Index: Video Games and the Body of Motion Capture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

III. Here Be Dragons: the (Pre)History of the Adventure Game

III. Here Be Dragons: the (pre)history of the adventure game The past is like a broken mirror, as you piece it together you cut yourself. Your image keeps shifting and you change with it. MAX PAYNE 2: THE FALL OF MAX PAYNE At the end of the Middle Ages, Europe’s thousand year sleep – or perhaps thousand year germination – between antiquity and the Renaissance, wondrous things were happening. High culture, long dormant, began to stir again. The spirit of adventure grew once more in the human breast. Great cathedrals rose, the spirit captured in stone, embodiments of the human quest for understanding. But there were other cathedrals, cathedrals of the mind, that also embodied that quest for the unknown. They were maps, like the fantastic, and often fanciful, Mappa Mundi – the map of everything, of the known world, whose edges both beckoned us towards the unknown, and cautioned us with their marginalia – “Here be dragons.” (Bradbury & Seymour, 1997, p. 1357)1 At the start of the twenty-first century, the exploration of our own planet has been more or less completed2. When we want to experience the thrill, enchantment and dangers of past voyages of discovery we now have to rely on books, films and theme parks. Or we play a game on our computer, preferably an adventure game, as the experience these games create is very close to what the original adventurers must have felt. In games of this genre, especially the older type adventure games, the gamer also enters an unknown labyrinthine space which she has to map step by step, unaware of the dragons that might be lurking in its dark recesses. -

Why John Madden Football Has Been Such a Success

Why John Madden Football Has Been Such A Success Kevin Dious STS 145: The History of Computer Game Design: Technology, Culture, Business Professor: Henry Lowood March 18, 2002 Kevin Dious STS 145: The History of Computer Game Design: Technology, Culture, Business Professor: Henry Lowood March 18, 2002 Why John Madden Football Has Been Such A Success Case History Athletic competition has been a part of the human culture since its inception. One of the most popular and successful sports of today’s culture is American football. This sport has grown into a worldwide phenomenon, and like the video game industry, has become a multi-billion entity. It was only a matter of time until game developers teamed up with the National Football League (NFL) to bring magnificent sport to video game players across the globe. There are few, if any, game genres that are as popular as sports games. With the ever-increasing popularity of the NFL, it was inevitable that football games would become one of the most lucrative of the sports game genre. With all of the companies making football games for consoles and PCs during the late 1980s and 1990s, there is one particular company that clearly stood and remains above the rest, Electronic Arts. EA Sports, the sports division of Electronic Arts, revolutionized not only the football sports games but also the entire sports game genre itself. Before Electronic Arts entered the sports realm, league licenses, celebrity endorsements, and re-release of games were all unheard of. EA was one of the first companies to release the same game annually, creating several series of games that are thriving even today. -

Internet Camera the D-Link SECURICAM Network DCS-2100 Internet Automatically Add It to the Network

Remote Audio & Video Surveillance for Home/Office View Full Motion Video of Your Home or Office over the Internet 4x Digital Zoom1 Magnifies Image for Enhanced Viewing Captures Video in Minimal DCS-2100 Lighting2 – Ideal for use at Night Remotely Take Snapshots and Save to a Hard Drive via Web Browser Starts Recording and Sends E-mail Alerts When Motion is Detected 10/100 Fast Ethernet Internet Camera The D-Link SECURICAM Network DCS-2100 Internet automatically add it to the network. The DCS-2100 can Camera is designed for office and home users who want be accessed and viewed from “My Network Places” as a a full-featured surveillance system that provides remote, device on the network. high quality video and audio monitoring over the Internet. By signing up with one of the many free Dynamic DNS The DCS-2100 connects directly to an Ethernet broadband services available on the web, you can create a personal network to enable remote viewing and management of web address (e.g., www.mycamera.myddns.com) the camera from anywhere in the world using Internet for your camera. This allows you to remotely access Explorer version 6. With its own IP address and built-in your camera and monitor your site without having to web server, you can place the DCS-2100 anywhere on remember the IP address, even if it has been changed the network without requiring a direct connection to a PC. by your Internet Service Provider. As you watch and listen remotely to video and sound Full-featured software is included to enhance the obtained by the DCS-2100, you can instantly take monitoring and management of the DCS-2100. -

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

Video-Based Interactive Storytelling

4 Video-Based Interactive Storytelling This thesis proposes a new approach to video-based interactive narratives that uses real-time video compositing techniques to dynamically create video sequences representing the story events generated by planning algorithms. The proposed approach consists of filming the actors representing the characters of the story in front of a green screen, which allows the system to remove the green background using the chroma key matting technique and dynamically compose the scenes of the narrative without being restricted by static video sequences. In addition, both actors and locations are filmed from different angles in order to provide the system with the freedom to dramatize scenes applying the basic cinematography concepts during the dramatization of the narrative. A total of 8 angles of the actors performing their actions are shot using a single or multiple cameras in front of a green screen with intervals of 45 degrees (forming a circle around the subject). Similarly, each location of the narrative is also shot from 8 angles with intervals of 45 degrees (forming a circle around the stage). In this way, the system can compose scenes from different angles, simulate camera movements and create more dynamic video sequences that cover all the important aspects of the cinematography theory. The proposed video-based interactive storytelling model combines robust story generation algorithms, flexible multi-user interaction interfaces and cinematic story dramatizations using videos. It is based on the logical framework for story generation of the Logtell system, with the addition of new multi-user interaction techniques and algorithms for video-based story dramatization using cinematography principles. -

Appendix A. DEFINITIONS of TERMS

Appendix A. DEFINITIONS OF TERMS In this section, we provide more detailed information about each of these facets as well as indexing terms, examples of video game screenshots, and corresponding rules for applying these terms with regards to the related terms. 1.1 Artistic Style Facet The style facet provides a framework for selecting the predominant and recognizable visual appearance of a video game towards which its artistic features are intentionally directed. Style describes the overall aesthetic organization of the entities in the game, and provides a distinctive category shared by similarly designed games. Abstract The term “abstract” describes pure forms, so generally it does not go with games which have narrative contexts to accompany the gameplay (from Järvinen, 2002). This term has two child terms: fractal and text. Fractal is a form of algorithmic art created by computations calculating the movement and display of graphic objects. It tends to be symmetrical and geometric in appearance but encompasses all abstract visualizations of color and form. Psychedelic, a child term of fractal, refers to a specific abstract fractal style featuring “kaleidoscopically swirling patterns” in bright, multicolored entropic motifs, and is commonly found in rhythm games. Figure 18. Abstract: Tetris (1984) Figure 19. Fractal: Fractal: Make Blooms Not War (2011) Figure 20. Psychedelic: Dyad (2012) Text, on the other hand, refers to an abstract visual style where the artistic elements are completely conveyed through the use of text. This is more common in older video games such Legend of the Red Dragon (1989), Zork (1977) and other MUD games. Figure 21. Text: Legend of the Red Dragon (1989) Photorealism The term “photorealism” refers to “photographic likeness with reality” (p. -

Kq7-Alt-Inlay

TABLE OF CONTENTS GAME INSTALLATION GAME INSTALLATION ...................... ....................................... ..... ...................... .... ............ 3 WINDOWS'" INSTALLATION I. Place the KING'S OuESr VII CD disk into your computer's CD drive. PLAYING KING'S QUEST Vll .. ................................................................................ .............. 3 2. Start Windows. THE INTERFACE ........... .... .. ............................................................................. .. .......... ...... 4 3. Click on !File). 4. Select !Run). The Cursor ............ .. ........... ........................................... .......................... ... ................. 4 5. At the Command bar, type the letter of your CD drive, followed by ":\sETUP.EXE" Inventory Objects .... ................... .... ........ ... .... .... .. ...... .. ....... .. .. .................. ................. 5 and click on OK or press !ENTER). For example. if the letter of your CD drive is "D", type "D:\sETUP.EXE" and click on OK or press !ENTER). Controls Icon ...................... .. ........... .. ................ .............................. ... ... ..................... 6 6. Follow the on-screen installation instructions. Scroller Slide Control ........................................................................................ .. ...... 6 7. Check the "README.TXT" file for the latest information. Windows 15 a trademark or Mlcrosoh Corpora1lon The ">>" Button .... ................... .............. ...................................... -

Christy Marx

Write Your Way Into Animation and Games Write Your Way Into Animation and Games Create a Writing Career in Animation and Games Christy Marx AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK © 2010 Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec- tronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, fur- ther information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organiza- tions such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treat- ment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluat- ing and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. -

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

Download 80 PLUS 4983 Horizontal Game List

4 player + 4983 Horizontal 10-Yard Fight (Japan) advmame 2P 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) nintendo 1941 - Counter Attack (Japan) supergrafx 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) mame172 2P sim 1942 (Japan, USA) nintendo 1942 (set 1) advmame 2P alt 1943 Kai (Japan) pcengine 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) mame172 2P sim 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) mame172 2P sim 1943 - The Battle of Midway (USA) nintendo 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) mame172 2P sim 1945k III advmame 2P sim 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) mame172 2P sim 2010 - The Graphic Action Game (USA, Europe) colecovision 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) fba 2P sim 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) mame078 4P sim 36 Great Holes Starring Fred Couples (JU) (32X) [!] sega32x 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) fba 2P sim 3D Crazy Coaster vectrex 3D Mine Storm vectrex 3D Narrow Escape vectrex 3-D WorldRunner (USA) nintendo 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) [!] megadrive 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) supernintendo 4-D Warriors advmame 2P alt 4 Fun in 1 advmame 2P alt 4 Player Bowling Alley advmame 4P alt 600 advmame 2P alt 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) advmame 2P sim 688 Attack Sub (UE) [!] megadrive 720 Degrees (rev 4) advmame 2P alt 720 Degrees (USA) nintendo 7th Saga supernintendo 800 Fathoms mame172 2P alt '88 Games mame172 4P alt / 2P sim 8 Eyes (USA) nintendo '99: The Last War advmame 2P alt AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (E) [!] supernintendo AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (UE) [!] megadrive Abadox - The Deadly Inner War (USA) nintendo A.B. -

Intro by the Admin

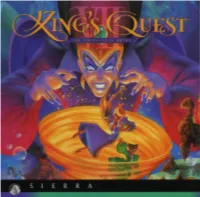

The Sierra Chest Newsletter: Issue 2, May 2009 Intro by the admin Dear Sierra fans, Another busy month of construction on the Sierra Chest. Most notably “Gabriel Knight 3: Blood of the Sacred, Blood of the Damned” has been inserted. And while that took far more time than expected, the result is great! More info about that on the next page. We also worked a bit on King’s Quest, and fully inserted “Lost in Time” by Coktel Vision. Some general stuff, such as a load of box arts have been added and it is now also possible to access the fanbased Empire Earth servers through the Chest. Also our friends at UnityHQ, member of the Sierra Gateway and fanbased home of the No One Lives Forever forums and servers, have a small request for you. It is a pleasure to say that, after some 200 uploaded videos on the Sierra Chest’s Youtube channel over the past half a year, we finally nailed an honor! The video “Gabriel Knight 3: Fiction versus Reality” was among the most watched videos in the video gaming category in France on April 26th. It was a small honor, which lasted only a day, but it was an honor nonetheless, so it is gratifying to see things are beginning to fall in the public spotlight. The video combines real locations with Gabriel Knight 3 gameplay and then shifts towards the vampire story during the 2nd half of the video, all guided by music of W. A. Mozart’s Requiem. With the number of subscribers to the Sierra Chest Youtube channel increasing by about 50% over the past month alone, we are confident more fans will find their way to the site and the Sierra Gateway forums (http://www.sierraforums.com). -

Intro by the Admin

The Sierra Chest Newsletter: Issue 4, August 2009 Intro by the admin Dear Sierra fans, The Sierra Chest got some structural upgrades last month. We started running a bit out of space, so it’s been upgraded to 150MB now, though it looks like we’ll have to double it again soon. Although the videos are outsourced to the Sierra Chest’s Youtube channel, an increasing number of images have been uploaded. With the increased space, we’ve been uploading a whole bunch of box arts. The box arts for all 250 games in the database should be uploaded by the end of this month. We have also received some emails, asking why certain games are not covered in the Sierra Chest. No worries, we are well aware of that. In fact, not even half of all Sierra games are in it yet. Those guys made a LOT. We just prefer to first fill up the pages of the games that are inserted at this point. Takes a while to fill it up, but we have received an increasing number of contributors, mostly from people offering to have their videos embedded on the site, which we of course gladly do. Aside from the increased space, we have also made some changes on the “general” page of each game. Instead of now having just 1 page, we inserted a filter where the user can chose between “general description”, “making of”, “box art”, “trailers”, “credits” and more, depending on what is available for each game. That makes the “general“page more user-friendly since you can immediately see what is available without having to scroll down all the time.