Domestication Effects on Aggressiveness: Comparison of Biting Motivation and Bite Force Between Wild

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Species of Exotic Passerine in Venezuela

COTINGA 7 Three species of exotic passerine in Venezuela Chris Sharpe, David Ascanio and Robin Restall Se presentan registros de tres especies exóticas de Passeriformes, sin previos registros en Ven ezuela. Lonchura malacca fue encontrado en junio de 1996 en Guacara, cerca de Valencia: hay evidencia anecdótica que sugiere que la especie ha colonizado algunas áreas de los Llanos. Lonchura oryzivora, una popular ave de jaula, parece estar bien establecida en áreas al oeste y norte del país, p.e. en Caricuao y Maracay. Passer domesticus fue encontrado en el puerto La Guaira en agosto-septiembre de 1996, donde parece estar nidificando. Se está tramitando una licencia para exterminar la especie en Venezuela. Introduction lation in the Caricuao area appears to have been Three new species of exotic passerine have appar established for a number of years, as do others near ently become established in northern Venezuela, Maracay (M. Lentino pers. comm. 1996). Specimens each of them representing new documented records for the cage-bird trade apparently come from for the country. Acarigua, a major area for rice cultivation (RR). The species is native to Java and Bali in South- East Asia, with introduced populations in many parts of the world including Florida, USA, and Puerto Rico. It is apparently only able to maintain stable populations where rice is plentiful1, such as the Acarigua–Barinas area, although the true na ture of its ecological requirements in Venezuela is unknown. Tricoloured Munia Lonchura malacca (Lyn Wells) Tricoloured Munia Lonchura malacca On 18 June 1996 a presumed colony of Tricoloured Munia was found in a roadside meadow close to Guacara near the city of Valencia. -

Second Supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-List of North American Birds

A O U Check-listSupplement The Auk 117(3):847-858, 2000 FORTY-SECOND SUPPLEMENT TO THE AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION CHECK-LIST OF NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS This first Supplementsince publication of the 7th Icterusprosthemelas, Lonchura cantans, and L. atricap- edition (1998)of the AOU Check-listof North American illa); (3) four speciesare changed(Caracara cheriway, Birdssummarizes changes made by the Committee Glaucidiumcostaricanum, Myrmotherula pacifica, Pica on Classification and Nomenclature between its re- hudsonia)and one added (Caracaralutosa) by splits constitutionin late 1998 and 31 January2000. Be- from now-extralimital forms; (4) four scientific causethe makeupof the Committeehas changed sig- namesof speciesare changedbecause of genericre- nificantly since publication of the 7th edition, it allocation (Ibycter americanus,Stercorarius skua, S. seemsappropriate to outline the way in which the maccormicki,Molothrus oryzivorus); (5) one specific currentCommittee operates. The philosophyof the name is changedfor nomenclaturalreasons (Baeolo- Committeeis to retain the presenttaxonomic or dis- phusridgwayi); (6) the spellingof five speciesnames tributional statusunless substantial and convincing is changedto make them gramaticallycorrect rela- evidenceis publishedthat a changeshould be made. tive to the genericname (Jacameropsaureus, Poecile The Committee maintains an extensiveagenda of atricapilla,P. hudsonica,P. cincta,Buarremon brunnein- potential actionitems, includingpossible taxonomic ucha);(7) oneEnglish name is changedto conformto -

Java Sparrow Padda Oryzivora in Quindío, Colombia Una Especie Exótica Y Amenazada, En Vida Silvestre: Padda Oryzivora En Quindío, Colombia

An escaped, threatened species: Java Sparrow Padda oryzivora in Quindío, Colombia Una especie exótica y amenazada, en vida silvestre: Padda oryzivora en Quindío, Colombia Thomas Donegan c/o Fundación ProAves, Cra. 20 #36–61, Bogotá, Colombia. Email: [email protected] Abstract captive populations may have conservation value in addition A photograph and sound recording of an escaped Java to raising conservation concerns. This short note includes Sparrow are presented from Quindío, Colombia. Although observations of an escapee in depto. Quindío. the species is previously reported in the upper Cauca valley, no prior confirmed photographic record exists nor records in On 17-19 December 2012, I spent three mornings sound this department. recording birds in secondary habitats in the grounds of Hotel Campestre Las Camelias, mun. Armenia, Quindío Key words New record, Java Sparrow, photograph, (c.04°31’N, 75°47’W). On the first of these days at escaped species, Colombia. approximately 7 am, I came across a Java Sparrow hopping along a path in the hotel grounds (Fig. 1). The bird was seen at very close quarters (down to 2 m) and identified Resumen immediately due to its distinctive plumage. I knew the Se presentan fotos y grabaciones de Padda oryzivora especie species previously from zoos and aviaries in Europe and the exótica en vida silvestre en Quindío, Colombia. Aunque la plate in McMullan et al. (2010). As I approached the bird especie se ha reportado antes en el valle del río Cauca, no over a period of 5-10 minutes, it flushed various times, but existen registros confirmados por fotografía ni registros en el was only capable of flying short distances (up to 5m) and a departamento. -

First Records of White-Capped Munia Lonchura Ferruginosa in Sumatra

Kukila 15 2011 103 First records of White-capped Munia Lonchura ferruginosa in Sumatra MUHAMMAD IQBAL KPB-SOS, Jalan Tanjung api-api km 9 Komplek P & K Blok E 1 Palembang 30152. Email : [email protected] Ringkasan. Burung Bondol oto-hitam merupakan jenis endemik Jawa dan Bali. Pada tanggal 4 Agustus 2007, dua individu teramati di persawahan di Kota Belitang, Sumatera Selatan. Catatan ini, ditambah dengan satu bukti foto dari Liwa (Lampung) dan lima burung yang dilaporkan pedagang burung ditangkap di Sungai Lilin (Sumatera Selatan) menunjukkan bahwa jenis ini sepertinya telah menyebar di bagian Selatan Sumatera. On the morning of 4 August 2007, whilst watching several munias in a paddy field about 2 km from Belitang (4°15’S, 104°26’E), I observed two White- capped Munias Lonchura ferruginosa perched on ripe rice plants. Belitang is the capital city of Ogan Komering Ulu Timur District in the province of South Sumatra. I focused on the diagnostic head pattern, which differed from the White-headed Munia L. maja in having a black throat and breast (Plate 1), as shown in a photograph taken at the time (see Ed’s. note below). The centre of the belly and under tail coverts were black, and the rump and upper tail coverts had a maroon gloss. In addition, at least five White-capped Munias were discovered among White-headed Munias in a cage in Sungai Lilin, Musi Banyuasin district, South Sumatra (Plate 2). The bird trader who owned the cage reported that the birds were caught in rice fields around Sungai Lilin. There is currently little agreement on the taxonomy or English name of this taxon. -

Breeding of Lonchura Punctulata (Scaly-Breasted Munia) from Sagaing University of Education Campus

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 9, Issue 1, January 2019 700 ISSN 2250-3153 Breeding of Lonchura punctulata (Scaly-breasted Munia) from Sagaing University of Education Campus Nwe Nwe Khaing Department of Biology, Sagaing University of Education , Sagaing Division, Myanmar DOI: 10.29322/IJSRP.9.01.2019.p8586 http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.9.01.2019.p8586 Abstract- Nests, eggs, clutch size, incubation and reproductive success of Lonchura panctulala (Scaly-breasted Munia) were observed from August 2017 to July 2018 at Sagaing University of Education Campus. Among the total of 57 nests, 41 nests (71.93%) were recorded as successful, 16 nests (28.07%) were observed as failure during the breeding season. Thirty five nests were found in Khayay trees (Mimuscops elengi), Ten nests were recorded in Saugainvillea spectabilis (Sekku - pan) Shrub, eight nests were observed in Cycas sp (monding). Small tree, Two nests were conducted in Pterocarpus macrocarpus (Paduk tree) Rose wood and Two nests were also recorded in Casuarina equisetifolia (Pinle kabwe). Among the total of 57 nests, 202 eggs and 105 hatchlings were observed during the breeding season. Index Terms- Eggs, Juveniles, Hatchlings, Reproductive Success I. INTRODUCTION Birds are conspicuous found everywhere. They indicate seasonal symbol. Many ecologists feel that birds are one of the most visible indicators of the total productivity of such biotic system. Life history studies identified many important biological attributes by species (Bent, 1963 cited by Welty, 1982). The Scaly-breasted Munia or spotted munia (Lonchura punctulata) is endemic to Asia and occurs from India and Sri Lanka, east to Indonesia and the Phillippines. -

West Papua 28 June – 3 August 2018

West Papua 28 June – 3 August 2018 Rob Gordijn & Helen Rijkes ([email protected]) - http://www.penguinbirding.com Introduction West Papua was the third stop in our year of travelling. Visiting Papua had been on our wish list for years and since West Papua has become a lot easier in recent years in terms of logistics and is still a lot cheaper than PNG we decided to primarily focus on the BOP’s (and other specialties) on the Indonesian side. (After our trip to West Papua we travel to PNG but there we focus mainly on the surrounding islands.) This report covers the 5,5-week trip to West Papua where we visited Numfor & Biak, Sorong (inc. Klasow Valley), Waigeo, Nimbokrang, Snow Mountains and the Arfaks. We were joined for most of the trip by Sjoerd Radstaak (Sorong until Arfaks), Marten Hornsveld, Vivian Jacobs, Bas Garcia (Waigeo until Arfaks) and Sander Lagerveld (Nimbokrang & Snow Mountains). Sander also visited the surroundings of Merauke (Wasur NP) for some southern specialities. Since we are still traveling this is a preliminary trip report with our main findings and a rough annotated species list (counts are incomplete and subspecies indication is missing). Sjoerd improved this tripreport enormously with his contribution. Please send us an email if you are missing information. Itinerary Day 1 Thursday 28 June 06:20 Manokwari. 14.00 ferry to Numfor (planned departure 11:00) Day 2 Friday 29 June Numfor Day 3 Saturday 30 June Travel Numfor to Biak (07.30-08.30) – birding Biak in afternoon Day 4 Sunday 1 July Biak Day 5 Monday 2 July -

Munias of Mt. Abu (Rajasthan, India) with Special Emphasis on Threatened Green Munia Amandava Formosa Satya P

Indian Birds Vol. 1 No. 4 (July-August 2005) 77 Munias of Mt. Abu (Rajasthan, India) with special emphasis on threatened Green Munia Amandava formosa Satya P. Mehra1, Sarita Sharma2 and Reena Mathur3 1Kesar Bhawan, 90, B/D Saraswati Hosp., Ganeshnagar, Pahada, Udaipur 313001, Rajasthan, India. Email: [email protected]. 2C/O Mr. L. L. Sharma, village Gol, via Jawal, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India. 3Professor, Department of Zoology, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. Email: [email protected]. Introduction 112.98km2 is under unnotified sanctuary Distribution of Munias cCann (1942) spent a short holiday at area (Anonymous 2003). Mt. Abu Wildlife Above 1,500m: Gurushikhar and Bhairon ka MMt. Abu and wrote, “It is an ‘oasis’ Sanctuary is long and narrow in shape, but Pathar are two prominent points within this in the Rajputana desert, and a delightful the top spreads out into a picturesque range. Only White-throated Munia was place for a holiday”. On the one hand, the plateau, which is about 19km in length and sighted within this altitudinal range. Green rain-fed eastern side is full of semi-evergreen 5-8km in breadth. Munia was sighted around Taramandal and deciduous flora, on the other, the drier (Planetarium), at 1,630m. Methodology western side gives way to xerophytic and 1,200-1,500m: Charlie Point (Jalara Fields), Regular seasonal surveys were conducted deciduous plants (Champion 1961). In this Achalgarh, Oriya Village, Trevor’s Tank, from January 2004 – August 15, 2005. Notes varied habitat is found a diverse avifauna Palanpur Point, Jawai Dam, Shergaon, Kodra were taken on different species and the (Mehra & Sharma, in prep.). -

(2) December 2018 P 47 Establishment and Spread of the Scaly-Breasted Munia in Mississippi

47 The Mississippi Kite 48 (2) ESTABLISHMENT AND SPREAD OF THE SCALY-BREASTED MUNIA (LONCHURA PUNCTULATA) IN MISSISSIPPI Susan Epps1 and Jason D. Hoeksema2 1 Diamondhead, MS 39525 2 Department of Biology, University of Mississippi P.O. Box 1848 University, MS 38677 OVERVIEW The Scaly-breasted Munia (Lonchura punctulata), also known as Nutmeg Mannikin or Spice Finch in the pet trade, is a finch (Estrildidae) species native to Asia. Due to its popularity in the pet trade, and its ability to naturalize post-release, it has become well established in numerous locations outside its native range (eBird 2018). In the United States, there are established populations in Hawaii, California, Texas, Florida, and less extensive populations in a few other states (eBird 2018). Reports of the species have increased in southern Mississippi in recent years (eBird 2018). The purposes of this paper are to summarize the history of its occurrence in Mississippi, and report some observations on its life history in this non-native part of its range. We utilized eBird reports, miscellaneous sightings reported to the Mississippi Bird Records Committee and on social media, and detailed field observations by one of us (Epps). Scaly-breasted Munias were first reported from Mississippi during November 2010 at Diamondhead in eastern Hancock County, and have since been consistently reported from Diamondhead. Three years passed before another report came from elsewhere in Mississippi, when reports started coming from Jackson and eastern Harrison counties. No reports came from outside of Diamondhead during 2015. Munias were reported from December 2018 The Mississippi Kite 48 (2) 48 Long Beach in western Harrison County, not far from Diamondhead, during 2016. -

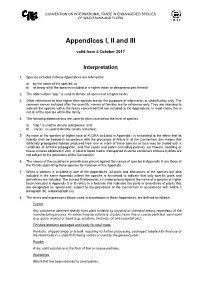

Appendices I, II and III (Valid from 4 October 2017)

CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA Appendices I, II and III valid from 4 October 2017 Interpretation 1. Species included in these Appendices are referred to: a) by the name of the species; or b) as being all of the species included in a higher taxon or designated part thereof. 2. The abbreviation “spp.” is used to denote all species of a higher taxon. 3. Other references to taxa higher than species are for the purposes of information or classification only. The common names included after the scientific names of families are for reference only. They are intended to indicate the species within the family concerned that are included in the Appendices. In most cases this is not all of the species within the family. 4. The following abbreviations are used for plant taxa below the level of species: a) “ssp.” is used to denote subspecies; and b) “var(s).” is used to denote variety (varieties). 5. As none of the species or higher taxa of FLORA included in Appendix I is annotated to the effect that its hybrids shall be treated in accordance with the provisions of Article III of the Convention, this means that artificially propagated hybrids produced from one or more of these species or taxa may be traded with a certificate of artificial propagation, and that seeds and pollen (including pollinia), cut flowers, seedling or tissue cultures obtained in vitro, in solid or liquid media, transported in sterile containers of these hybrids are not subject to the provisions of the Convention. -

Polymorphic Sequence in the ND3 Region of Java Endemic Ploceidae Birds Mitochondrial DNA

BIODIVERSITAS ISSN: 1412-033X (printed edition) Volume 12, Number 2, April 2011 ISSN: 2085-4722 (electronic) Pages: 70-75 DOI: 10.13057/biodiv/d120203 Polymorphic sequence in the ND3 region of Java endemic Ploceidae birds mitochondrial DNA R. SUSANTI♥ Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Semarang State University. Bld. D6, Fl. 1. Sekaran Campus, Gunungpati, Semarang 50229, Central Java, Indonesia. Tel & Fax. +62-24-8508033. ♥email: [email protected]; [email protected] Manuscript received: 22 July 2010. Revision accepted: 14 February 2011. ABSTRACT Susanti R (2011) Polymorphic sequence in the ND3 region of Java endemic Ploceidae birds mitochondrial DNA. Biodiversitas 12: 70- 75. As part of biodiversity, Ploceidae bird family must be kept away from extinction and degradation of gene-diversity. This research was aimed to analyze ND3 gene from mitochondrial DNA of Java Island endemic of Ploceidae bird. Each species of Ploceidae birds family was identified based on their morphological character, then the blood sample was taken from the birds nail vein. DNA was isolated from blood using Dixit method. Fragment of ND3 gene was amplified using PCR method with specific primer pairs and sequenced using dideoxy termination method with ABI automatic sequencer. Multiple alignment of ND3 nucleotide sequences were analyzed using ClustalW of MEGA-3.1 program. Estimation of genetic distance and phylogenetic tree construction were analyzed with Neighbor-Joining method and calculation of distance matrix with Kimura 2 –parameter. The result of Java Island endemic of Ploceidae bird family exploration showed that Erythrura hyperythra and Lonchura ferruginosa can not be found anymore in nature, but the Lonchura malacca that are not actually Java island endemic was also found. -

Movements on the Federal Front

Volume II • Number 1 • FEBRUARY 1975 DEDICATED TO CONSERVATION OF BIRD WILDLIFE THROUGH ENCOURAGEMENT OF CAPTIVE BREEDING PROGRAMS, SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH, AND EDUCATION OF THE GENERAL PUBLIC Movements on the Federal Front by Jerry Jennings Tremors are being felt from Washington as the Erythrura trichroa Tri-colored Parrot Finch Erythrura psittacea Red-headed Parrot Finch sluggish machinery of the USDI begins to grind out Erythrura cyaneovirens Fiji Red-headed Parrot Finch the final version of the "Injurious Wildlife Proposal" Chloebia gouldiae Gouldian Finch Aidemosyne modesto Cherry (Plum-headed) Finch An unofficial, tentative list of "low risk" birds has Lonchura striata Society Finch been obtained by the pet industry as a result of the Amandina fasciata Cut-throat Finch Ad Hoc Committee negotiations between the USDI Family PLOCEIDAE and PIJAC*. Though the list is a step forward from Vidua chalybeata Combassou the original proposal's list of four birds it is still Vidua funerea Black Indigo Bird more noteworthy for what it restricts than what Vidua wilsoni it allows. Vidua hypocherina Resplendent Whydah Vidua fischeri Fischer's Whydah The following species will be allowed importation Vidua macroura Pintail Whydah into the U.S. without permit: Vidua regia Shaft-tail Whydah Vidua paradisaea Paradise Whydah Vidua orienta/is Broad-tailed Whydah Family PHASIANIDAE Family FRINGILLIDAE Colinus virginianus Bobwhite Quail Alectoris graeca (incl. A. chukar) Chukar Partridge Serinus leucopygius Grey Singing Finch Perdix perdix Hungarian (Gray) Partridge -

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 1 16( 1 ):90— 107

2007. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 1 16( 1 ):90— 107 SKELETAL CHARACTERS AND THE SYSTEMATICS OF ESTRILDID FINCHES (AVES: ESTRILDIDAE) J. Dan Webster: Department of Biology, Hanover College, Hanover, Indiana 47243 USA ABSTRACT. The family Estrildidae contains 108 to 140 species arranged in 15 to 40 genera and two to nine tribes or subfamilies. In this study 401 skeletons belonging to 103 species and 27 genera were compared, as well as 75 skeletons of 15 genera of possibly related forms; skeletal characters add to the existing characters of behavioral, external anatomical, and molecular features. Best skeletal characters for generic separation were shape of the caudal basibranchial and a combination (PCA) of mensural characters. Pholidornis is not an estrildid. The classification of Goodwin (1982) was affirmed with these changes: Tribes should be dropped. The genus Lepidopygia should be lumped in Lonchura. Additional taxonomic changes are cautiously suggested. Keywords: Wax-billed finches, Africa, Australia, southern Asia, Indo-Pacific islands The finches studied here have variously nized 9 tribes and 33 genera. Mayr (1968) rec- been called waxbills, grass finches, manikins, ognized 25 genera, but did not list every spe- munias, etc. They inhabit Africa, Australia, cies; he utilized Delacour's three tribes, but southern Asia, and the Indo-Pacific islands, moved four genera to different tribes. Mayr, and have been widely kept and studied in avi- Paynter & Traylor (1968) recognized three aries worldwide. From 108-140 species of Es- tribes and 27 genera. Goodwin (1982) recog- trildidae, arranged in 15—40 genera, are rec- nized 27 genera and 132 species—not quite ognized by recent authorities.