Writing Sample

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Spartan Daily ] Senior Communications Major Monica Cal- Onize at SJSU, Said Negrete](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0449/spartan-daily-senior-communications-major-monica-cal-onize-at-sjsu-said-negrete-1770449.webp)

Spartan Daily ] Senior Communications Major Monica Cal- Onize at SJSU, Said Negrete

Wednesday October 21, 2009 Serving San José State University since 1934 Volume 133, Issue 27 SPORTS]]]OPINION A&E SJSU volleyball team Facebook shows writer 'Groundswell' tackles finally spikes a win the power of one person poverty in South Africa Page 5 Page 7 Page 4 Temp teachers could fail to make the cut New fraternity builds path As SJSU faces further budget cuts, students contracts that are renewed as paying for, especially with this Linder said. “I am a temporary could find fewer part-time teachers next year needed, Harris said. increase in tuition,” senior ki- contract employee. I knew that to charter Harris said the university is nesiology major Ana Aranda when I signed the agreement.” By Jennifer Hadley 40,000 students over (the) next not prepared to share the num- said. “Fewer professors on Senior psychology major By Dominique Dumadaug Staff Writer two years,” said Erik Fallis, a ber of part-time instructors em- campus would only bring more Steve Dominguez said the po- Staff Writer CSU media relations specialist. ployed at SJSU this semester, negative eff ects.” tential of having fewer faculty s student enrollment is re- Pat Lopes Harris, director because the university is wait- Harris said when the uni- worries him. arco Negrete, a junior Aduced on California State of media relations at SJSU, ing on the CSU chancellor’s of- versity chooses to not renew a “It makes me insecure know- Mpublic relations major, University campuses, some said tenured or tenure-track fi ce to collect census data from contract, it is not technically a ing that there will be less sec- said he had no intention of faculty contracts may not be instructors are employees who every CSU campus. -

The Tangle of It

Reid MacDonald 109,300 words 553 Valim Way Author’s personal draft Sacramento, CA 95831 Printed on 11/5/14 (626) 354-0679 [email protected] THE TANGLE OF IT by Reid McFarland THE TANGLE of IT by Reid McFarland ⁂ For Vickie We’ve been apart for some time now I don’t know how to navigate these waters I love you and hope we can find some calm harbor ⁂ Herein tells a story where not all times and places match Forgive me those who are in the know So goes the way of memory and invention ⁂ McFarland / The Tangle of It Chapter 1. FRANNY'S CANDIES “I roll the Kettledrum candy in my mouth.” Franny pictures herself chewing on Boston Fruit Slices and her jaw flexes automatically. “Chewy wedges taste lemon and lime and go BOOM-bah-BOOM when I bite into one.” She adds, “When I unwrap a second Kettledrum out of its tight parchment, I examine the sour and sugar-copper rind. They are better enjoyed in pairs. Tomás, why aren’t Kettledrum candies hard? Like Lifesavers or Butterscotches? When they clink against your teeth, they could sound like a snare or a top hat. I can hear a soft bass rumble a tympani symphony deep within me. I swear, the Kettledrums make my voice go baritone when I sing BOOM-bah-BOOM after eating one. It’s true: I’ve tried it!” Franny confesses this to me under her gummy-bear breath and I agree unconditionally the way a best friend must. We come here because most of her schoolmates do not make their way down the block to Doña Dolce. -

2010 Annual Report

Invite and connect t. ohn’s people to God and one an- S J other through evangelical Christ’s lutheran love church 2010 Our hope is that, Annual as your faith continues to grow, our sphere of Report activity among you will greatly expand. —2 Corinthians 10:15 (NIV) 2 ST. JOHN’S LUTHERAN CHURCH—2010 ANNUAL REPORT Reports from Ministry Staff St. John’s Church Council Senior Pastor .............................................................................................3 Executive Committee Associate Pastor of Worship Arts and Missions ...................................4 President ...........................Dan Lammers Associate Pastor of Family Ministries and Adult Discipleship ..........5 Vice President ................... Bob Hinshaw Associate Pastor of Member Care and Senior Ministries ...................6 Secretary ..........................David Johnson Junior High Ministry ...............................................................................7 Treasurer ...................... Chuck Hurliman Joy Zone Children’s Ministries ...............................................................8 Senior High Youth Ministry ...................................................................9 Ministry Teams and Liaisons DinnerTime ............................................................................................10 Adult Discipleship ...............Ann Stemm 2010 Reports Children’s Ministry ................Ray Dostal Church Council and Committees Finance ......................... Chuck Hurliman Congregational Council ........................................................................11 -

OCTOBER, 2011 Cornell University Anabel Taylor Chapel Ithaca, New

THE DIAPASON OCTOBER, 2011 Cornell University Anabel Taylor Chapel Ithaca, New York Cover feature on pages 26–28 Oct 2011 Cover.indd 1 9/14/11 11:28:13 AM Oct 2011 pp. 2-18.indd 2 9/14/11 11:33:05 AM THE DIAPASON Letters to the Editor A Scranton Gillette Publication One Hundred Second Year: No. 10, Whole No. 1223 OCTOBER, 2011 St. Thomas Fifth Avenue gal pad endlessly redesigning the organ Established in 1909 ISSN 0012-2378 Will Carter (Letters, September 2011) and console layout—adding a Trompette An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, seems to be confused as to whether the here, moving a Septième there. At the the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music organ of St. Thomas Church in New York time I thought this was pretty terrifi c. is or is not still the work of G. Donald Nomenclature is not the real issue. Harrison. As one who has played recitals The signifi cance of this organ on so on it regularly since 1971, I contend that many different levels, and its preserva- CONTENTS Editor & Publisher JEROME BUTERA [email protected] it is not. The best documentation that I tion, are. 847/391-1045 can offer to support this is the letter of Much of Harrison’s basic conception, FEATURES March 21, 1968 from Philip Steinhaus, his console, his layout of divisions, his The organ and disaster relief: Associate Editor JOYCE ROBINSON Executive Vice President of the Aeoli- Great without chorus reeds, his Swell An American organist in Japan [email protected] by Roger W. -

Read Razorcake Issue #36 As a PDF

So Very Unsexy shove—but any more rules than that, and it’s only a matter of time that I thought of this in Gainesville, Florida at The Fest. I was in your brushstrokes of good intentions have you painted into a corner. ZRQGHU 1R ¿JKWV 1R EXOOVKLW *UHDW SHRSOH *UHDW PXVLF $Q Here’s the connection: Too often, the folks who have the most expertly planned, large event. How’d this happen? “expert without actually doing it” advice are the ones who want more I’m not deaf, but I do admit that ninety-eight percent of the time rules enforced because they don’t feel in control of the situation; ZKHQ,KHDU³+H\GXGH\RXVKRXOGBBBBBBBBB ¿OOLQWKHEODQN hell, they may even have the best of intentions. But, ultimately, they with the zine. That’d totally keep it from suckin’,” I’m no longer want to steer from the back seat—yank the wheel—want to have paying attention. I’m picturing this really cute, fuzzy otter and he’s equal time without equal effort. They have the opportunity to walk ÀRDWLQJRQKLVEDFNWU\LQJWRFUDFNRSHQWKLVFODPZLWKDURFN0DQ away from a car you built if they wreck it. ,ORYHWKDWRWWHUJHWWLQJDOO'DUZLQRQWKHVKHOO¿VKORXQJLQJLQWKH ,¶OOOHW\RXLQRQDFRXSOHRIVHFUHWV 5D]RUFDNH¶VQRWEOLQGO\ ocean, being all cute, calm, and concentrated. And by the time the groping along, bumping into things, and somehow a zine ploops out person’s done telling me what I should do—without them offering of heinies every two months. It’s a lot of very tedious, constant work to take up the task they’re suggesting—that little otter’s opened WKDWLVVRYHU\XQVH[\WKDWLW¶VERULQJWRHYHQEULHÀ\PHQWLRQZKDW up that shell; he smiles as he eats. -

Floodwall Volume2, Issue3 Spring 2021 Floodwall Volume2, Issue3 Spring 2021

Floodwall volume2, issue3 spring 2021 Floodwall volume2, issue3 spring 2021 Cover: Andrew Youngblom, Confict and Hybrid of Plant and Ghost Floodwall volume2, issue3 spring 2021 managing editor: Amy Kielmeyer assistant managing editor: Meghan Bird prose editors: Haley Hamilton & Eric Iliff poetry editors: Brittney Christy & Amy Kielmeyer photography & art editor: Anna Kinney special section editor: Mykell Stavem chief copy editor: Madison Knoll social media editors: Elise Unterseher & Myra Henderson prose readers: Brooke Kruger, Olivia Kost, Brenden Kimpe, Adam Sorenson, Maria Matsakis, Christina Walker, & Jona L. Pedersen poetry readers: Haylee Bjork, Samuel Amendolar, Sarah Miller, Macy Marquette, Anaka Grenier, Abigail Petersen, & Shilo Previti photography & art readers: Iris Mlnarik, Allison Lundmark, Hailey Narloch, Elizabeth Waldorf, Leah Hanley, Grant McMillan, & Abigail Petersen special section readers: Myra Henderson, Meghan Bird, David Larson, Erin Timpe, & Elise Unterseher copy editors: Myra Henderson, Meghan Bird, & Maria Matsakis designers & layout: ENGL 234 (“Intro to Writing, Editing, & Publishing”) students faculty advisor: Dr. Patrick Henry Floodwall is a production of students at the University of North Dakota. The magazine is produced by volunteers and students in the ENGL 234 course. Submissions to Floodwall are open only to University of North Dakota students during our open calls. Submission guidelines and back issues are available on the Floodwall website: https://arts-sciences.und.edu/academics/english/foodwall- magazine/. Copyright © 2021, the contributors. No portion of Floodwall may be reprinted without permission from the contributor. From the Editors Floodwall returns . with our biggest issue yet! Founded in spring 2012 by graduate students at the University of North Dakota, Floodwall published fve issues of creative writing, interviews, and reviews, featuring writers from across the nation. -

Corpus Antville

Corpus Epistemológico da Investigação Vídeos musicais referenciados pela comunidade Antville entre Junho de 2006 e Junho de 2011 no blogue homónimo www.videos.antville.org Data Título do post 01‐06‐2006 videos at multiple speeds? 01‐06‐2006 music videos based on cars? 01‐06‐2006 can anyone tell me videos with machine guns? 01‐06‐2006 Muse "Supermassive Black Hole" (Dir: Floria Sigismondi) 01‐06‐2006 Skye ‐ "What's Wrong With Me" 01‐06‐2006 Madison "Radiate". Directed by Erin Levendorf 01‐06‐2006 PANASONIC “SHARE THE AIR†VIDEO CONTEST 01‐06‐2006 Number of times 'panasonic' mentioned in last post 01‐06‐2006 Please Panasonic 01‐06‐2006 Paul Oakenfold "FASTER KILL FASTER PUSSYCAT" : Dir. Jake Nava 01‐06‐2006 Presets "Down Down Down" : Dir. Presets + Kim Greenway 01‐06‐2006 Lansing‐Dreiden "A Line You Can Cross" : Dir. 01‐06‐2006 SnowPatrol "You're All I Have" : Dir. 01‐06‐2006 Wolfmother "White Unicorn" : Dir. Kris Moyes? 01‐06‐2006 Fiona Apple ‐ Across The Universe ‐ Director ‐ Paul Thomas Anderson. 02‐06‐2006 Ayumi Hamasaki ‐ Real Me ‐ Director: Ukon Kamimura 02‐06‐2006 They Might Be Giants ‐ "Dallas" d. Asterisk 02‐06‐2006 Bersuit Vergarabat "Sencillamente" 02‐06‐2006 Lily Allen ‐ LDN (epk promo) directed by Ben & Greg 02‐06‐2006 Jamie T 'Sheila' directed by Nima Nourizadeh 02‐06‐2006 Farben Lehre ''Terrorystan'', Director: Marek Gluziñski 02‐06‐2006 Chris And The Other Girls ‐ Lullaby (director: Christian Pitschl, camera: Federico Salvalaio) 02‐06‐2006 Megan Mullins ''Ain't What It Used To Be'' 02‐06‐2006 Mr. -

Caddie Woodlawn Carol Ryrie Brink

CADDIE WOODLAWN CAROL RYRIE BRINK WINNER OF THE NEWBERY MEDAL 1 Three Adventurers In 1864 Caddie Woodlawn was eleven, and as wild a little tomboy as ever ran the woods of western Wisconsin. She was the despair of her mother and of her elder sister, Clara. But her father watched her with a little shine of pride in his eyes, and her brothers accepted her as one of themselves without a question. Indeed, Tom, who was two years older, and Warren, who was two years younger than Caddie, needed Caddie to link them together into an inseparable trio. Together they got in and out of more scrapes and adventures than any one of them could have imagined alone. And in those pioneer days, Wisconsin offered plenty of opportunities for adventure to three wide-eyed, red-headed youngsters. On a bright Saturday afternoon in the early fall, Tom and Caddie and Warren Woodlawn sat on a bank of the Menomonie River, or Red Cedar as they call it now, taking off their clothes. Their red heads shone in the sunlight. Tom's hair was the darkest, Caddie's the nearest golden, and nine-year-old Warren's was plain carrot color. Not one of the three knew how to swim, but they were going across the river nevertheless. A thin thread of smoke beyond the bend on the other side of the river told them that the Indians were at work on a birch-bark canoe. "Do you think the Indians around here would ever get mad and massacre folks like they did up north?" wondered Warren, tying his shirt up in a little bundle. -

To Search This List, Hit CTRL+F to "Find" Any Song Or Artist Song Artist

To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Song Artist Length Peaches & Cream 112 3:13 U Already Know 112 3:18 All Mixed Up 311 3:00 Amber 311 3:27 Come Original 311 3:43 Love Song 311 3:29 Work 1,2,3 3:39 Dinosaurs 16bit 5:00 No Lie Featuring Drake 2 Chainz 3:58 2 Live Blues 2 Live Crew 5:15 Bad A.. B...h 2 Live Crew 4:04 Break It on Down 2 Live Crew 4:00 C'mon Babe 2 Live Crew 4:44 Coolin' 2 Live Crew 5:03 D.K. Almighty 2 Live Crew 4:53 Dirty Nursery Rhymes 2 Live Crew 3:08 Fraternity Record 2 Live Crew 4:47 Get Loose Now 2 Live Crew 4:36 Hoochie Mama 2 Live Crew 3:01 If You Believe in Having Sex 2 Live Crew 3:52 Me So Horny 2 Live Crew 4:36 Mega Mixx III 2 Live Crew 5:45 My Seven Bizzos 2 Live Crew 4:19 Put Her in the Buck 2 Live Crew 3:57 Reggae Joint 2 Live Crew 4:14 The F--k Shop 2 Live Crew 3:25 Tootsie Roll 2 Live Crew 4:16 Get Ready For This 2 Unlimited 3:43 Smooth Criminal 2CELLOS (Sulic & Hauser) 4:06 Baby Don't Cry 2Pac 4:22 California Love 2Pac 4:01 Changes 2Pac 4:29 Dear Mama 2Pac 4:40 I Ain't Mad At Cha 2Pac 4:54 Life Goes On 2Pac 5:03 Thug Passion 2Pac 5:08 Troublesome '96 2Pac 4:37 Until The End Of Time 2Pac 4:27 To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Ghetto Gospel 2Pac Feat. -

Poetry of Place in Putnam County Megan Carter

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Student research Student Work 2014 Bridging: Poetry of Place in Putnam County Megan Carter Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Carter, Megan, "Bridging: Poetry of Place in Putnam County" (2014). Student research. Paper 4. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bridging Poetry of Place in Putnam County Megan Carter 2 CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………4 Walking…………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Leafing……………………………………………………………………………………6 Looking for Soil ………………………………………………………………………...14 Mapping …………………………………………………………………….18 Fueling………………………………………………………………………………….. 22 Driving…………………………………………………………………………………………..27 Remembering: East…………………………………………………………………….28 West……………………………………………………………………………………...36 South…………………………………………………………………………………… 40 North…………………………………………………………………………………….52 Bridging…………………………………………………………………………………………60 Reflecting………………………………………………………………………………..61 Centering………………………………………………………………………………..66 Sitting, Watching Seeds………………………………………………………………...71 Processing……………………………………………………………………………………….76 3 Acknowledgments In writing this paper, I want to first acknowledge the work of my body, especially my eyes and ears for putting up with me. I also want to thank my Broca’s area for putting up with my desire to further my language skills and understand the rhythms of words in nature. I want to thank the leaves around DePauw—I appreciate that you didn’t disintegrate in the winter when I needed you most. Thanks for allowing me to place some of you back in the trees in order to defy nature but to better my craft. Thanks to the trees for sticking around. -

Avalentine's Events Heavy on Love in 2018

Valentine’s events heavy on love in 2018 bout halfway through winter in speechless for just $50! To schedule your The evening will include a first-class dinner, Masteroff and Harnick’s She Loves Me, Southwest Montana, the snow singing Valentine for Wednesday, February followed by dancing to the swing of Adam February 9th–18th, at the beautifully cover and chilly temps are like- 14th, call (406) 548-1391. Please note: the Greenberg’s Bridger Mountain Big Band, restored Rialto theater. Friday and Saturday ly here to stay. But there’s Chord Rustlers will travel to accommodate featuring vocalist Valarie Andrews. Share the performances begin at 7:30pm, followed by something else in the crisp Valentines throughout the Gallatin Valley. evening with someone special, or invite a Sunday matinees at 3pm. A special February air: the warm fuzzies Rockin’ TJ Ranch will present friend to dine and dance the night away. The Thursday presentation is set for Feb. 15th at of love giving area residents all Sweethearts of Bozeman, a night of event begins at 6:30pm. Tickets are $75 per 7:30pm. She Loves Me is a delightful romantic the feels. Valentine’s Day is right around the Valentine-inspired dinner theatre, on person and $150 for couples. Visit comedy that soars through the exhilarating corner and several venues (and traveling gen- Wednesday, February 14th beginning at www.theellentheatre.com for more and sometimes confusing anticipation of tlemenA crooners) are set to play host to 6pm. Round up your sweetheart, family, or information. love. Sales clerks in a Hungarian parfumerie, romantic events that’ll hope to thaw even the friends for a fun-filled evening featuring a The Rialto hosts An Intimate Georg and Amalia spend their days quarrel- most stubborn hearts. -

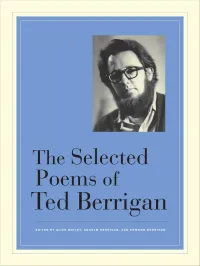

Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan

The Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Humanities Endowment Fund of the University of California Press Foundation. The publisher also gratefully acknowledges the generous support of Jamie and David Wolf and the Rosenthal Family Foundation as members of the Publisher’s Circle of the University of California Press Foundation. The Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan Edited by Alice Notley, Anselm Berrigan, and Edmund Berrigan University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press, one of the most distinguished univer- sity presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institu- tions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2011 by The Regents of the University of California Poems from The Sonnetsby Ted Berrigan, copyright © 2000 by Alice Notley, Literary Executrix of the Estate of Ted Berrigan. Used by per- mission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Berrigan, Ted. [Poems. Selections] The selected poems of Ted Berrigan / edited by Alice Notley, Anselm Berrigan, and Edmund Berrigan. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn: 978-0-520-26683-4 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn: 978-0-520-26684-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) I. Notley, Alice 1945– II. Berrigan, Anselm. III. Berrigan, Edmund, 1974– IV. Title.