C:\My Documents\Dailey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York

The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and The Politics of New York NEIL J. SULLIVAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX This page intentionally left blank THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX yankee stadium and the politics of new york N EIL J. SULLIVAN 1 3 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paolo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2001 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN 0-19-512360-3 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Carol Murray and In loving memory of Tom Murray This page intentionally left blank Contents acknowledgments ix introduction xi 1 opening day 1 2 tammany baseball 11 3 the crowd 35 4 the ruppert era 57 5 selling the stadium 77 6 the race factor 97 7 cbs and the stadium deal 117 8 the city and its stadium 145 9 the stadium game in new york 163 10 stadium welfare, politics, 179 and the public interest notes 199 index 213 This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments This idea for this book was the product of countless conversations about baseball and politics with many friends over many years. -

John "Red" Braden Legendary Fort Wayne Semi- Pro Baseball Manager

( Line Drives Volume 18 No. 3 Official Publication of the Northeast Indiana Baseball Association September 2016 •Formerly the Fort Wayne Oldtimer's Baseball Association* the highlight of his illustrious career at that point in John "Red" Braden time but what he could not know was that there was Legendary Fort Wayne Semi- still more to come. 1951 saw the Midwestern United Life Insurance Pro Baseball Manager Co. take over the sponsorship of the team (Lifers). In He Won 5 National and 2 World Titles 1952 it was North American Van Lines who stepped By Don Graham up to the plate as the teams (Vans) sponsor and con While setting up my 1940s and 50s Fort Wayne tinued in Semi-Pro Baseball and Fort Wayne Daisies displays that role at the downtown Allen County Public Library back for three in early August (August thru September) I soon years in realized that my search for an LD article for this all, 1952, edition was all but over. And that it was right there '53 and in front of me. So here 'tis! '54. Bra- A native of Rock Creek Township in Wells Coun dens ball ty where he attended Rock Creek High School and clubs eas participated in both baseball and basketball, John ily made "Red" Braden graduated and soon thereafter was it to the hired by the General Electric Co. Unbeknownst to national him of course was that this would become the first tourna step in a long and storied career of fame, fortune and ment in notoriety, not as a G.E. -

Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter De Rosa Bridgewater State College

Bridgewater Review Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 7 Jun-2004 Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter de Rosa Bridgewater State College Recommended Citation de Rosa, Peter (2004). Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918. Bridgewater Review, 23(1), 11-14. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol23/iss1/7 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Boston Baseball Dynasties 1872–1918 by Peter de Rosa It is one of New England’s most sacred traditions: the ers. Wright moved the Red Stockings to Boston and obligatory autumn collapse of the Boston Red Sox and built the South End Grounds, located at what is now the subsequent calming of Calvinist impulses trembling the Ruggles T stop. This established the present day at the brief prospect of baseball joy. The Red Sox lose, Braves as baseball’s oldest continuing franchise. Besides and all is right in the universe. It was not always like Wright, the team included brother George at shortstop, this. Boston dominated the baseball world in its early pitcher Al Spalding, later of sporting goods fame, and days, winning championships in five leagues and build- Jim O’Rourke at third. ing three different dynasties. Besides having talent, the Red Stockings employed innovative fielding and batting tactics to dominate the new league, winning four pennants with a 205-50 DYNASTY I: THE 1870s record in 1872-1875. Boston wrecked the league’s com- Early baseball evolved from rounders and similar English petitive balance, and Wright did not help matters by games brought to the New World by English colonists. -

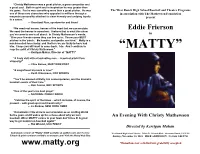

Christy Mathewson Was a Great Pitcher, a Great Competitor and a Great Soul

“Christy Mathewson was a great pitcher, a great competitor and a great soul. Both in spirit and in inspiration he was greater than his game. For he was something more than a great pitcher. He was The West Ranch High School Baseball and Theatre Programs one of those rare characters who appealed to millions through a in association with The Mathewson Foundation magnetic personality attached to clean honesty and undying loyalty present to a cause.” — Grantland Rice, sportswriter and friend “We need real heroes, heroes of the heart that we can emulate. Eddie Frierson We need the heroes in ourselves. I believe that is what this show you’ve come to see is all about. In Christy Mathewson’s words, in “Give your friends names they can live up to. Throw your BEST pitches in the ‘pinch.’ Be humble, and gentle, and kind.” Matty is a much-needed force today, and I believe we are lucky to have had him. I hope you will want to come back. I do. And I continue to reap the spirit of Christy Mathewson.” “MATTY” — Kerrigan Mahan, Director of “MATTY” “A lively visit with a fascinating man ... A perfect pitch! Pure virtuosity!” — Clive Barnes, NEW YORK POST “A magnificent trip back in time!” — Keith Olbermann, FOX SPORTS “You’ll be amazed at Matty, his contemporaries, and the dramatic baseball events of their time.” — Bob Costas, NBC SPORTS “One of the year’s ten best plays!” — NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO “Catches the spirit of the times -- which includes, of course, the present -- with great spirit and theatricality!” -– Ira Berkow, NEW YORK TIMES “Remarkable! This show is as memorable as an exciting World Series game and it wakes up the echoes about why we love An Evening With Christy Mathewson baseball. -

A National Tradition

Baseball A National Tradition. by Phyllis McIntosh. “As American as baseball and apple pie” is a phrase Americans use to describe any ultimate symbol of life and culture in the United States. Baseball, long dubbed the national pastime, is such a symbol. It is first and foremost a beloved game played at some level in virtually every American town, on dusty sandlots and in gleaming billion-dollar stadiums. But it is also a cultural phenom- enon that has provided a host of colorful characters and cherished traditions. Most Americans can sing at least a few lines of the song “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” Generations of children have collected baseball cards with players’ pictures and statistics, the most valuable of which are now worth several million dollars. More than any other sport, baseball has reflected the best and worst of American society. Today, it also mirrors the nation’s increasing diversity, as countries that have embraced America’s favorite sport now send some of their best players to compete in the “big leagues” in the United States. Baseball is played on a Baseball’s Origins: after hitting a ball with a stick. Imported diamond-shaped field, a to the New World, these games evolved configuration set by the rules Truth and Tall Tale. for the game that were into American baseball. established in 1845. In the early days of baseball, it seemed Just a few years ago, a researcher dis- fitting that the national pastime had origi- covered what is believed to be the first nated on home soil. -

![ABSTRACT Title of Document: [Re]Integrating the Stadium](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5615/abstract-title-of-document-re-integrating-the-stadium-475615.webp)

ABSTRACT Title of Document: [Re]Integrating the Stadium

ABSTRACT Title of Document: [Re]integrating the Stadium Within the City: A Ballpark for Downtown Tampa Justin Allen Cullen Master of Architecture, 2012 Directed By: Professor Garth C. Rockcastle, FAIA Architecture With little exception, Major League Baseball stadiums across the country deprive their cities of valuable space when not in use. These stadiums are especially wasteful if their resource demands are measured against their utilization. Baseball stadiums are currently utilized for only 13% of the total hours of each month during a regular season. Even though these stadiums provide additional uses for their audiences (meeting spaces, weddings, birthdays, etc.) rarely do these events aid the facility’s overall usage during a year. This thesis explores and redevelops the stadium’s interstitial zone between the street and the field. The primary objective is to redefine this zone as a space that functions for both a ballpark and as part of the urban fabric throughout the year. [RE]INTEGRATING THE STADIUM WITHIN THE CITY: A BALLPARK FOR DOWNTOWN TAMPA By Justin Allen Cullen Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture 2012 Advisory Committee: Professor Garth C. Rockcastle, Chair Assistant Professor Powell Draper Professor Emeritus Ralph D. Bennett Glenn R. MacCullough, AIA © Copyright by Justin Allen Cullen 2012 Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my family and friends who share my undying interest in our nation’s favorite pastime. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my parents and my fiancé, Kiley Wilfong, for their love and support during this six-and-a-half year journey. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Dope Sheet Week 9 (Vs. Pit) WEB SITE.Qxd

Packers Public Relations z Lambeau Field Atrium z 1265 Lombardi Avenue z Green Bay, WI 54304 z 920/569-7500 z 920/569-7201 fax Jeff Blumb, Director; Aaron Popkey, Assistant Director; Zak Gilbert, Assistant Director; Sarah Quick, Coordinator; Adam Woullard, Coordinator VOL VII; NO. 15 GREEN BAY, NOV. 1, 2005 EIGHTH GAME PITTSBURGH (5-2) at GREEN BAY (1-6) AND IN 1992: Pittsburgh’s 1992 trip to Lambeau Field was a milestone Sunday, Nov. 6 z Lambeau Field z 3:15 p.m. CST z CBS game, too. It marked the first NFL start for Brett Favre. XFavre also used the occasion to launch an NFL-record for consecutive THIS WEEK’S NOTABLE STORYLINES: starts by a quarterback, 212 entering the weekend, Since that day, a 17- XUnder the leadership of Head Coach Mike Sherman 3 win over rookie head coach Bill Cowher, 187 other quarterbacks have and quarterback Brett Favre, the Packers continue started an NFL game, including the Steelers’ Ben Roethlisberger. The to exhibit a steady outlook in their approach and 49ers’ Alex Smith joined the list Oct. 9. perspective — something highly unexpected given XDuring the 2005 season, four quarterbacks have made their first NFL the team’s 1-6 start and substantial injuries. starts: Brooks Bollinger (N.Y. Jets), Kyle Orton (Chicago), Alex Smith XThe Steelers return to Lambeau Field for the first (San Francisco) and J.P. Losman (Buffalo). time in a decade. It’s also the teams’ first meeting XAlso, 20 NFL teams during the period have started at least 10 quarter- in seven years. -

Base Ball." Clubs and Players

COPYRIGHT, 1691 IY THE SPORTING LIFE PUB. CO. CHTEHED AT PHILA. P. O. AS SECOND CLASS MATTER. VOLUME 17, NO. 4. PHILADELPHIA, PA., APRIL 25, 1891. PRICE, TEN GENTS. roof of bis A. A. U. membership, and claim other scorers do not. AVhen they ecore all rial by such committee. points in the game nnw lequircd with theuav LATE NEWS BY WIRE. "The lea::ue of American Wheelmen shall an- the game is played they have about d ne all EXTREME VIEWS ually, or at such time and for such periods as they ean do." Louisville Commercial. t may deetn advisable, elect a delegate who hall act with and constitute one of the board of A TIMELY REBUKE. ON THE QUESTION OF PROTECTION THE CHILDS CASE REOPENED BY THE governors of the A. A. U. and shall have a vote upon all questions coming before said board, and A Magnate's Assertion of "Downward BALTIMORE CLUB. a right to sit upon committees and take part in Tendency of Professional Sport" Sharply FOR MINOR LEAGUES. all the actions thereof, as fully as members of Kesciitcd. ail board elected from the several associations The Philadelphia Press, in commenting i Hew League Started A Scorers' Con- f the A. A. U., and to the same extent and in upon Mr. Spalding's retirement, pays that Some Suggestions From the Secretary ike manner as the delegates from the North gentleman some deserved compliments, but wntion Hews of Ball American Turnerbund. also calls him down rather sharply for some ol One ol the "Nurseries "Xheso articles of alliance shall bo terminable unnecessary, indiscreet remarks in connec ly either party upon thirty day's written notice tion with the game, which are also calcu ol Base Ball." Clubs and Players. -

Baseball News Clippings

! BASEBALL I I I NEWS CLIPPINGS I I I I I I I I I I I I I BASE-BALL I FIRST SAME PLAYED IN ELYSIAN FIELDS. I HDBOKEN, N. JT JUNE ^9f }R4$.* I DERIVED FROM GREEKS. I Baseball had its antecedents In a,ball throw- Ing game In ancient Greece where a statue was ereoted to Aristonious for his proficiency in the game. The English , I were the first to invent a ball game in which runs were scored and the winner decided by the larger number of runs. Cricket might have been the national sport in the United States if Gen, Abner Doubleday had not Invented the game of I baseball. In spite of the above statement it is*said that I Cartwright was the Johnny Appleseed of baseball, During the Winter of 1845-1846 he drew up the first known set of rules, as we know baseball today. On June 19, 1846, at I Hoboken, he staged (and played in) a game between the Knicker- bockers and the New Y-ork team. It was the first. nine-inning game. It was the first game with organized sides of nine men each. It was the first game to have a box score. It was the I first time that baseball was played on a square with 90-feet between bases. Cartwright did all those things. I In 1842 the Knickerbocker Baseball Club was the first of its kind to organize in New Xbrk, For three years, the Knickerbockers played among themselves, but by 1845 they I had developed a club team and were ready to meet all comers. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Baseball Spectatorship in New York City, 1876-1890 A

THE EVOLUTION OF A BALLPARK SOCIETY: BASEBALL SPECTATORSHIP IN NEW YORK CITY, 1876-1890 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Guelph by BEN ROBINSON In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts April, 2009 © Ben Robinson, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your Me Votre ref6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-58408-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-58408-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.