FFDH Complaint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Debating Diversity Following the Widely Publicized Deaths of Black Tape

KENNEDY SCHOOL, UNDER CONSTRUCTION. The Harvard Kennedy School aims to build students’ capacity for better public policy, wise democratic governance, international amity, and more. Now it is addressing its own capacity issues (as described at harvardmag.com/ hks-16). In January, as seen across Eliot Street from the northeast (opposite page), work was well under way to raise the level of the interior courtyard, install utility space in a new below-grade level, and erect a four-story “south building.” The project will bridge the Eliot Street opening between the Belfer (left) and Taubman (right) buildings with a new “gateway” structure that includes faculty offices and other spaces. The images on this page (above and upper right) show views diagonally across the courtyard from Taubman toward Littauer, and vice versa. Turning west, across the courtyard toward the Charles Hotel complex (right), affords a look at the current open space between buildings; the gap is to be filled with a new, connective academic building, including classrooms. Debating Diversity following the widely publicized deaths of black tape. The same day, College dean Toward a more inclusive Harvard African-American men and women at the Rakesh Khurana distributed to undergrad- hands of police. Particularly last semester, uates the results of an 18-month study on di- Amid widely publicized student protests a new wave of activism, and the University’s versity at the College. The day before, Presi- on campuses around the country in the last responses to it, have invited members of the dent Drew Faust had joined students at a year and a half, many of them animated by Harvard community on all sides of the is- rally in solidarity with racial-justice activ- concerns about racial and class inequities, sues to confront the challenges of inclusion. -

Harvard to Build New Campus Center; Donor Secured to Back Project - Harvard - Your Campus - Boston.Com

Harvard to build new campus center; donor secured to back project - Harvard - Your Campus - Boston.com MORE CAMPUSES Sign In | Register now HARVARD < Back to front page Text size – + Connect to Harvard HARVARD Follow @YCHarvard on Twitter Harvard to build new campus center; Click here to follow Your Campus Harvard on donor secured to back project Twitter. Posted by Matt Rocheleau September 19, 2013 01:05 PM ADVERTISEMENT 0 Comments (0) 1 1 0 E-mail story Print story Other Boston Area Campuses Facebook Twitter Pinterest Share Share Boston College Boston University By Matt Rocheleau, Town Correspondent Brandeis Emerson Harvard University will soon begin planning for a new campus center after securing Harvard MIT donor funding for the project, a campus official said. Northeastern Suffolk More details, including the identity of the donor, are expected to be released this fall, Tufts the official said, confirming a report last week by the Harvard Crimson student Wellesley newspaper, which quoted university president Drew Faust. UMass Boston Simmons Berklee Faust told the Crimson the new campus center will likely be constructed in the Holyoke Babson Center building and would include a range of spaces for community gatherings, Bentley parties, academic events, meetings, and studying. The donation for the project comes as part of a multi-year major fundraising campaign Recent blog posts called The Harvard Campaign, which was announced last spring and is scheduled to When does Spring Break start? A handy calendar for many formally launch on Saturday, Sept. 21, the official said. colleges Comcast testing new Internet-streamed TV service Planning for the project will include input from administrators, students, campus designed for college campuses at Emerson housing officials and faculty, the official said. -

Edward Channing's Writing Revolution: Composition Prehistory at Harvard

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2017 EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851 Bradfield dwarE d Dittrich University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Dittrich, Bradfield dwarE d, "EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 163. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/163 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851 BY BRADFIELD E. DITTRICH B.A. St. Mary’s College of Maryland, 2003 M.A. Salisbury University, 2009 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English May 2017 ii ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ©2017 Bradfield E. Dittrich iii EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851 BY BRADFIELD E. DITTRICH This dissertation has been has been examined and approved by: Dissertation Chair, Christina Ortmeier-Hooper, Associate Professor of English Thomas Newkirk, Professor Emeritus of English Cristy Beemer, Associate Professor of English Marcos DelHierro, Assistant Professor of English Alecia Magnifico, Assistant Professor of English On April 7, 2017 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

Divestment May Burst the Carbon Bubble If Investors' Beliefs Tip To

Divestment may burst the carbon bubble if investors’ beliefs tip to anticipating strong future climate policy Birte Ewers,1;2;∗ Jonathan F. Donges,1;3;∗;# Jobst Heitzig1, Sonja Peterson4 1Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Member of the Leibniz Association, P.O. Box 60 12 03, 14412 Potsdam, Germany 2Department of Economics, University of Kiel, Olshausenstraße 40, 24098 Kiel, Germany 3Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, Kraftriket¨ 2B, 114 19 Stockholm, Sweden 4Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Kiellinie 66, 24105 Kiel, Germany ∗The first two authors share the lead authorship. #To whom correspondence should be addressed; E-mail: [email protected] February 21, 2019 To achieve the ambitious aims of the Paris climate agreement, the majority of fossil-fuel reserves needs to remain underground. As current national govern- ment commitments to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions are insufficient by far, actors such as institutional and private investors and the social movement on divestment from fossil fuels could play an important role in putting pressure on national governments on the road to decarbonization. Using a stochastic arXiv:1902.07481v1 [q-fin.GN] 20 Feb 2019 agent-based model of co-evolving financial market and investors’ beliefs about future climate policy on an adaptive social network, here we find that the dy- namics of divestment from fossil fuels shows potential for social tipping away from a fossil-fuel based economy. Our results further suggest that socially responsible investors have leverage: a small share of 10–20 % of such moral investors is sufficient to initiate the burst of the carbon bubble, consistent with 1 the Pareto Principle. -

OVERVIEW of ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION (ADR): a Handbook for Corps Managers

Pamphlet #5 ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE US Army Corps RESOLUTION SERIES of Engineers® OVERVIEW OF ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION (ADR): A Handbook for Corps Managers ..ON a,'Jl'!'DIENT I A;;proved tm ;uclic reieo.NI ~- I>----• JULY 1996 IWR PAMPHLET 96-ADR-P-5 19970103 016 The Corps Commitment to Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) This pamphlet is one in a series of pamphlets describing techniques for Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR). This series is part ofa Corps program to encourage its managers to develop and utilize new ways ofresolving disputes. ADR techniques may be used to prevent disputes, resolve them at earlier stages, or settle them prior to formal litigation. ADR is a new field, and additional techniques are being developed all the time. These pamphlets are a means ofproviding Corps managers with up-to-date information on the latest techniques. The information in this pamphlet is designed to provide a starting point for innovation by Corps managers in the use ofADR techniques. Other ADR case studies and working papers are available to assist managers. The current list ofpamphlets, case studies, and working papers in the ADR series is listed in the back ofthis pamphlet. The ADR Program is carried out under the proponency ofthe U.S. Army Corps ofEngineers, Office ofChief Counsel, Lester Edelman, ChiefCounsel, and with the guidance ofthe U.S. Army Corps ofEngineers' Institute for Water Resources (!WR), Alexandria VA. Frank Carr serves as ADR Program Manager. Jerome Delli Priscoli, Ph.D., Senior Policy Analyst of!WR currently serves as Technical Monitor, assisted by Donna Ayres, ADR Program Coordinator. James L. -

CRISIS of PURPOSE in the IVY LEAGUE the Harvard Presidency of Lawrence Summers and the Context of American Higher Education

Institutions in Crisis CRISIS OF PURPOSE IN THE IVY LEAGUE The Harvard Presidency of Lawrence Summers and the Context of American Higher Education Rebecca Dunning and Anne Sarah Meyers In 2001, Lawrence Summers became the 27th president of Harvard Univer- sity. Five tumultuous years later, he would resign. The popular narrative of Summers’ troubled tenure suggests that a series of verbal indiscretions created a loss of confidence in his leadership, first among faculty, then students, alumni, and finally Harvard’s trustee bodies. From his contentious meeting with the faculty of the African and African American Studies Department shortly af- ter he took office in the summer of 2001, to his widely publicized remarks on the possibility of innate gender differences in mathematical and scientific aptitude, Summers’ reign was marked by a serious of verbal gaffes regularly reported in The Harvard Crimson, The Boston Globe, and The New York Times. The resignation of Lawrence Summers and the sense of crisis at Harvard may have been less about individual personality traits, however, and more about the context in which Summers served. Contestation in the areas of university governance, accountability, and institutional purpose conditioned the context within which Summers’ presidency occurred, influencing his appointment as Harvard’s 27th president, his tumultuous tenure, and his eventual departure. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution - Noncommercial - No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecom- mons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. You may reproduce this work for non-commercial use if you use the entire document and attribute the source: The Kenan Institute for Ethics at Duke University. -

Lia Halloran

Martha Otero Lia Halloran Born: 1977 Chicago, IL Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA Assistant Professor of Art, Chapman University, Orange, CA Education: 2001 MFA, Yale University, New Haven, CT 1999 BFA, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 1998 Studio Art Centers International, Florence, Italy Solo Exhibitions: 2012 Sublimation | Transmutation, Martha Otero Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2010 Folding and Unfolding, Artisphere, Arlington VA The Only Way Out Is Through, DCKT Contemporary, New York, NY * 2008 Dark Skate, DCKT Contemporary, New York, NY Dark Skate Miami, Fredric Snitzer Gallery, Miami, FL Dark Skate, LaMontagne Gallery, Boston, MA 101 California Street, San Francisco, CA 2007 Dark Skate, DCKT Contemporary, Pulse London, London, UK 2006 The World is Bound with Secret Knots, DCKT Contemporary, New York, NY 2005 And the Darkness Implies the Vastness, Sandroni Rey, Los Angeles, CA 2001 Aesthetic Confinement; MFA Thesis Exhibition, Yale University School of Art, Green Hall Gallery, New Haven, CT Group Exhibitions: 2012 Tilt-Shift L.A. New Queer Perspectives on the Western Edge, Luis de Jesus Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2011 Haunted: Contemporary Photography / Video / Performance, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain Universe City, The Fine Arts Gallery at CSULA, Los Angeles, CA Critical Faculties, Guggenheim Gallery, Chapman University, Orange, CA. Oniomania, Martha Otero Gallery, Los Angeles, CA X-TRA’s, 1 Image 1 Minute, Angelenos Present Significant Images, Ray Kurtzman Theater Creative Arts Agency, Los Angeles, CA 2010 Girls Just Want to Have Funds, P.P.O.W Gallery, New York, NY Haunted: Contemporary Photography / Video / Performance, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain 820 N Fairfax Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90046 t. -

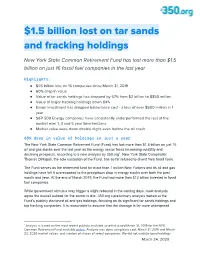

$1.5 Billion Lost on Tar Sands and Fracking Holdings

$1.5 billion lost on tar sands and fracking holdings New York State Common Retirement Fund has lost more than $1.5 billion on just 16 fossil fuel companies in the last year Highlights: ● $1.5 billion loss on 16 companies since March 31, 2019 ● 60% drop in value ● Value of tar sands holdings has dropped by 57% from $2 billion to $850 million ● Value of major fracking holdings down 84% ● Exxon investment has dropped below base cost - a loss of over $500 million in 1 year ● S&P 500 Energy companies have consistently underperformed the rest of the market over 1, 3 and 5 year time horizons ● Market value were down double digits even before the oil crash 60% drop in value of holdings in just a year The New York State Common Retirement Fund (Fund) has lost more than $1.5 billion on just 16 oil and gas stocks over the last year as the energy sector faces increasing volatility and declining prospects, according to a new analysis by 350.org1. New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, the sole custodian of the Fund, has so far refused to divest from fossil fuels. The Fund serves as the retirement fund for more than 1 million New Yorkers and its oil and gas holdings have left it overexposed to the precipitous drop in energy stocks over both the past month and year. At the end of March 2019, the Fund had more than $13 billion invested in fossil fuel companies. While government stimulus may trigger a slight rebound in the coming days, most analysts agree the overall outlook for the sector is dim. -

TRINITY COLLEGE Cambridge Trinity College Cambridge College Trinity Annual Record Annual

2016 TRINITY COLLEGE cambridge trinity college cambridge annual record annual record 2016 Trinity College Cambridge Annual Record 2015–2016 Trinity College Cambridge CB2 1TQ Telephone: 01223 338400 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.trin.cam.ac.uk Contents 5 Editorial 11 Commemoration 12 Chapel Address 15 The Health of the College 18 The Master’s Response on Behalf of the College 25 Alumni Relations & Development 26 Alumni Relations and Associations 37 Dining Privileges 38 Annual Gatherings 39 Alumni Achievements CONTENTS 44 Donations to the College Library 47 College Activities 48 First & Third Trinity Boat Club 53 Field Clubs 71 Students’ Union and Societies 80 College Choir 83 Features 84 Hermes 86 Inside a Pirate’s Cookbook 93 “… Through a Glass Darkly…” 102 Robert Smith, John Harrison, and a College Clock 109 ‘We need to talk about Erskine’ 117 My time as advisor to the BBC’s War and Peace TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 3 123 Fellows, Staff, and Students 124 The Master and Fellows 139 Appointments and Distinctions 141 In Memoriam 155 A Ninetieth Birthday Speech 158 An Eightieth Birthday Speech 167 College Notes 181 The Register 182 In Memoriam 186 Addresses wanted CONTENTS TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 4 Editorial It is with some trepidation that I step into Boyd Hilton’s shoes and take on the editorship of this journal. He managed the transition to ‘glossy’ with flair and panache. As historian of the College and sometime holder of many of its working offices, he also brought a knowledge of its past and an understanding of its mysteries that I am unable to match. -

Ad Hoc Committee on Fossil Fuel Divestment Report

TO: Tilak Lal, Chair, Joint Committee on Investments; Vice Chair, Rutgers University Board of Trustees J. Michael Gower, Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer, Rutgers University FROM: Ad Hoc Committee on Fossil Fuel Divestment SUBJECT: Divestment of the Rutgers University Endowment from Fossil Fuel Investments DATE: February 22, 2021 Introduction In spring 2020, the Joint Committee on Investments, which sets overall policy for the investment of the Rutgers University endowment, received a request from a student group called the Endowment Justice Collective to divest from fossil fuels. The chair of the Joint Committee on Investments and the university’s chief financial officer made a preliminary determination that the students’ request appeared to meet the standards outlined in the Advisory Statement on Divestment within the university’s Investment Policy. As prescribed by this policy, an ad hoc committee composed of faculty, students, and staff was charged to consider the divestment request based on university policy and to make recommendations based on its review.1 Fossil Fuels in the Rutgers University Endowment The Ad Hoc Committee defined fossil fuel investments as investments in any company or fund whose primary business is the exploration or extraction of fossil fuels, including coal, oil, and natural gas, or whose primary business supports this sector with infrastructure and other services. This definition is consistent with the nature of the divestment request received in spring 2020. Currently, approximately 5% of the university’s $1.5 billion endowment consists of fossil fuel investments. Sixty percent of these investments are in private funds, with the remainder in public equity or fixed income funds. -

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY REPORTER No 6488 W E D N E S D Ay 13 D E C E M B E R 2017 V O L C X Lv I I I N O 12

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY REPORTER NO 6488 W ED N E S D AY 13 D ECEMBER 2017 V OL CXLV III N O 12 CONTENTS Notices Examination in Nuclear Energy for the M.Phil. Calendar 173 Degree, 2017–18 177 Discussion on Tuesday, 23 January 2018 173 Examination in Future Infrastructure and Built Election to the Council 173 Environment for the M.Res. Degree, 2017–18 177 Election of a member of the Council’s Finance Examination in Integrated Photonic and Committee in class (b) 173 Electronic Systems for the M.Res. Degree, Cambridge Centre for Crop Science 174 2017–18 178 Project and Programme Governance Examination in Sensor Technologies and Guidelines for information technology and Applications for the M.Res. Degree, 2017–18 178 services 174 Reports Vacancies, appointments, etc. Joint Report of the Council and the General Vacancies in the University 174 Board on the governance of the Careers Service 179 Appointment and grants of title 175 Obituaries Notices by the General Board Obituary Notices 181 Senior Academic Promotions, 1 October 2018 Graces exercise: Committees 175 Graces submitted to the Regent House on Regulations for examinations 13 December 2017 182 Computer Science Tripos, Part IA 175 Acta Examination in Interdisciplinary Design for Approval of Grace submitted to the Regent the Built Environment for the M.St. Degree: House on 29 November 2017 182 Correction 176 End of the Official Part of the ‘Reporter’ Notices by Faculty Boards, etc. Examination in Bioscience Enterprise for the Report of Discussion M.Phil. Degree, 2017–18 176 Tuesday, 5 December 2017 183 Examination in Energy Technologies for the College Notices M.Phil. -

Climate Change: Active Stewardship Vs. Divestment

HNW_NRG_B_Inset_Mask Climate change: Active Stewardship vs. Divestment At RBC Global Asset Management (RBC GAM)1, we believe that climate change is a material and systemic risk that has the potential to impact the global economy, markets and society as a whole. As an asset manager and fiduciary of our clients’ assets, we have an important responsibility to consider all material factors that may impact the performance of our investments. In 2020, we took steps to formalize the actions we are taking to address climate change with the launch of Our approach to climate change. A cornerstone of this approach is active stewardship as an effective mechanism to motivate companies to build strategies that enable climate mitigation* and adaptation**. Some investors who are concerned about the impact of in extreme cases, the filing of lawsuits. As global investors climate change and are seeking to align their investment continue to integrate climate change into their investment strategies with these views have chosen a divestment decisions, active managers use both engagement and proxy approach. While RBC GAM does offer divestment solutions, voting as a means of better understanding and influencing we believe that the best approach to support the transition the activities or behaviour of issuers. to a low-carbon economy is through active stewardship. Engagement Active stewardship Engagement involves meeting with the boards and Active stewardship refers to the suite of actions investors management of issuers, typically corporations, and learning can take to better understand and influence the activities or about how they are approaching strategic opportunities and behaviour of issuers. It can be thought of as a conversation material risks in their business.