Divestment May Burst the Carbon Bubble If Investors' Beliefs Tip To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IPO Or Divestiture: Making Informed Decisions

IPO or divestiture: Making informed decisions By Yael Woodward Amaral, Partner, Accounting Advisory, KPMG in Canada To divest or go public. It is a simple proposition with complex considerations. No doubt, pursuing an initial public offering (IPO) is a viable option for private equity (PE) funds looking to raise cash from a portfolio asset they are not ready to part ways with, but like any major portfolio decision, it pays to go in with eyes wide open. Taking the IPO journey has its merits. Current market “ Going public is not a panacea for conditions are making it more difficult for funds to operate on a debt leverage model approach at the same levels of return. difficult times. As anyone who has As such, going public may be a mechanism to extract capital ventured down the IPO path can from the asset while maintaining ownership. attest, it only means trading one set of challenges for another.” The true cost of going public Even still, going public is not a panacea for difficult times. Economy of scale As anyone who has ventured down the IPO path can attest, It is one thing to say your organization wants to be public it only means trading one set of challenges for another. and another to be ready for the costs, compliance, and Whether raising a million dollars or a billion, going public public scrutiny that entails. The massive shift in the reporting means becoming beholden to new rules, processes, public environment alone can be a significant challenge for the shareholders and regulators. This can be unfamiliar territory under-prepared, as it demands significant financial reporting for funds that are used to working in a more autonomous capabilities, controls, IT infrastructure, human resource environment and selling acquisitions when the numbers deem considerations and governance that simply cannot be it best. -

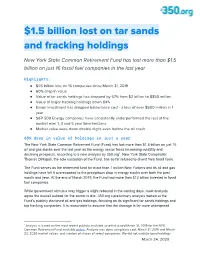

$1.5 Billion Lost on Tar Sands and Fracking Holdings

$1.5 billion lost on tar sands and fracking holdings New York State Common Retirement Fund has lost more than $1.5 billion on just 16 fossil fuel companies in the last year Highlights: ● $1.5 billion loss on 16 companies since March 31, 2019 ● 60% drop in value ● Value of tar sands holdings has dropped by 57% from $2 billion to $850 million ● Value of major fracking holdings down 84% ● Exxon investment has dropped below base cost - a loss of over $500 million in 1 year ● S&P 500 Energy companies have consistently underperformed the rest of the market over 1, 3 and 5 year time horizons ● Market value were down double digits even before the oil crash 60% drop in value of holdings in just a year The New York State Common Retirement Fund (Fund) has lost more than $1.5 billion on just 16 oil and gas stocks over the last year as the energy sector faces increasing volatility and declining prospects, according to a new analysis by 350.org1. New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, the sole custodian of the Fund, has so far refused to divest from fossil fuels. The Fund serves as the retirement fund for more than 1 million New Yorkers and its oil and gas holdings have left it overexposed to the precipitous drop in energy stocks over both the past month and year. At the end of March 2019, the Fund had more than $13 billion invested in fossil fuel companies. While government stimulus may trigger a slight rebound in the coming days, most analysts agree the overall outlook for the sector is dim. -

Global Corporate Divestment Study

2014 | ey.com/transactions EY | Assurance | Tax | Transactions | Advisory About EY GlobalEY is a global leader in assurance, tax, transaction and advisory services. The insights and quality services we deliver help build trust and confidence in the capital markets and in economies the world over. We develop outstanding leaders who team to deliver on our promises to all of our stakeholders. In so doing, we play a critical role in building a better working world for our people, for our Corporateclients and for our communities. EY refers to the global organization, and may refer to one or more, of the member firms of Ernst & Young Global Limited, each of which is a separate legal entity. Ernst & Young Global Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee, does not provide services to clients. For more information Divestmentabout our organization, please visit ey.com. Study About EY’s Transaction Advisory Services How you manage your capital agenda today will define Strategicyour competitive position tomorrow. divestments We work with clients to create social and economic value by helping them make better, more informed decisions about strategically managing capital and transactions in fast-changing drivemarkets. Whether value you’re preserving, optimizing, raising or investing capital, EY’s Transaction Advisory Services combine a unique set of skills, insight and experience to deliver focused advice. We help you drive competitive advantage and increased returns through improved decisions across all aspects of your capital agenda. © 2014 EYGM Limited. All Rights Reserved. EYG no. DE0493 ED 0115 This material has been prepared for general informational purposes only and is not intended to be relied upon as accounting, tax, or other professional advice. -

Ad Hoc Committee on Fossil Fuel Divestment Report

TO: Tilak Lal, Chair, Joint Committee on Investments; Vice Chair, Rutgers University Board of Trustees J. Michael Gower, Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer, Rutgers University FROM: Ad Hoc Committee on Fossil Fuel Divestment SUBJECT: Divestment of the Rutgers University Endowment from Fossil Fuel Investments DATE: February 22, 2021 Introduction In spring 2020, the Joint Committee on Investments, which sets overall policy for the investment of the Rutgers University endowment, received a request from a student group called the Endowment Justice Collective to divest from fossil fuels. The chair of the Joint Committee on Investments and the university’s chief financial officer made a preliminary determination that the students’ request appeared to meet the standards outlined in the Advisory Statement on Divestment within the university’s Investment Policy. As prescribed by this policy, an ad hoc committee composed of faculty, students, and staff was charged to consider the divestment request based on university policy and to make recommendations based on its review.1 Fossil Fuels in the Rutgers University Endowment The Ad Hoc Committee defined fossil fuel investments as investments in any company or fund whose primary business is the exploration or extraction of fossil fuels, including coal, oil, and natural gas, or whose primary business supports this sector with infrastructure and other services. This definition is consistent with the nature of the divestment request received in spring 2020. Currently, approximately 5% of the university’s $1.5 billion endowment consists of fossil fuel investments. Sixty percent of these investments are in private funds, with the remainder in public equity or fixed income funds. -

Ma Divestment 4-1-2021

BPB 2021-013 BEM 405 1 of 23 MA DIVESTMENT 4-1-2021 DEPARTMENT POLICY Medicaid (MA) ONLY Divestment results in a penalty period in MA, not ineligibility. Divestment policy does not apply to Qualified Disabled Working Individuals (QDWI); see Bridges Eligibility Manual (BEM) 169. Divestment is a type of transfer of a resource and not an amount of resources transferred. Divestment means the transfer of a resource (see resource defined in this item and in glossary) by a client or his spouse that are all the following: • Is within a specified time; see look back period in this item. • Is a transfer for less than fair market value; see definition in glossary. • Is not listed under transfers that are not divestment in this item. Note: See annuity not actuarially sound and joint owners and transfers in this item and BEM 401 about special transactions considered transfers for less than fair market value. During the penalty period, MA will not pay the client’s cost for: • Long Term Care (LTC) services. • Home and community-based waiver services. • Home help. • Home health. MA will pay for other MA-covered services. Do not apply a divestment penalty period when it creates an undue hardship; see undue hardship in this item. RESOURCE DEFINED Resource means all the client’s and spouse's assets and income. It includes all assets and all income, even countable and/or excluded assets, the individual or spouse receive. It also includes all assets and income that the individual (or spouse) were BRIDGES ELIGIBILITY MANUAL STATE OF MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES BPB 2021-013 BEM 405 2 of 23 MA DIVESTMENT 4-1-2021 entitled to but did not receive because of action by one of the following: • The client or spouse. -

Climate Change: Active Stewardship Vs. Divestment

HNW_NRG_B_Inset_Mask Climate change: Active Stewardship vs. Divestment At RBC Global Asset Management (RBC GAM)1, we believe that climate change is a material and systemic risk that has the potential to impact the global economy, markets and society as a whole. As an asset manager and fiduciary of our clients’ assets, we have an important responsibility to consider all material factors that may impact the performance of our investments. In 2020, we took steps to formalize the actions we are taking to address climate change with the launch of Our approach to climate change. A cornerstone of this approach is active stewardship as an effective mechanism to motivate companies to build strategies that enable climate mitigation* and adaptation**. Some investors who are concerned about the impact of in extreme cases, the filing of lawsuits. As global investors climate change and are seeking to align their investment continue to integrate climate change into their investment strategies with these views have chosen a divestment decisions, active managers use both engagement and proxy approach. While RBC GAM does offer divestment solutions, voting as a means of better understanding and influencing we believe that the best approach to support the transition the activities or behaviour of issuers. to a low-carbon economy is through active stewardship. Engagement Active stewardship Engagement involves meeting with the boards and Active stewardship refers to the suite of actions investors management of issuers, typically corporations, and learning can take to better understand and influence the activities or about how they are approaching strategic opportunities and behaviour of issuers. It can be thought of as a conversation material risks in their business. -

ASI Position Statement – Fossil Fuels April 2021

ASI Position Statement – Fossil Fuels April 2021 “ At ASI, consideration of climate-change risks and opportunities is an integral part of our investment process across all asset classes and sectors. We carefully consider fossil fuel related risks and the ability to transition to alternatives in our investment decisions.” 02 ASI Position Statement Fossil Fuels – Our Approach for Investments Financial risks related to fossil fuels are becoming more material the transition from more carbon-intensive fuels to gas where as pressure to decarbonise the global economy is growing. alternatives are limited. However, we also consider the risk of gas Aberdeen Standard Investments (ASI) fully acknowledges the role utilities and infrastructure becoming stranded in the medium to of fossil fuels in causing and further exacerbating climate change. long term. Transitioning directly to low-carbon energy sources We support the goals of the Paris Agreement, are members of the such as renewables is our preference and we strongly Net Zero Asset Manager initiative and believe that urgent action is encourage it. required to limit global warming to 1.5°C. This means aiming for a global net-zero emissions economy by 2050, in which fossil fuels Pounds of CO2 emitted per million Btu of energy will only play a minor role. On the path to that world, we need to transition to a low-carbon Natua as economy, in which fossil fuels are phased out and replaced with Gasoine cost effective and reliable alternatives. This needs to be a ‘just’ (witot ethano) transition where effects on communities, workers and energy Diese ue and security are carefully considered. -

Fossil Fuels Divestment

Fossil Fuels Divestment ww3.haverford.edu /fossilfuelsdivestment/ Dear Friends, Over the past year, many colleges and universities have investigated divestment of endowment from firms that have investments in fossil fuels as a way of applying financial leverage against the use of carbon- based energy while promoting alternative sources. Here at Haverford, the dialogue was initiated in the summer of 2012 by a number of thoughtful students who, consistent with a national campaign, specifically asked the College to freeze all endowment investments in 200 companies identified as having the greatest proven reserves of coal, oil, and natural gas and to unwind all existing investments in these companies over a five-year period. The matter was referred to our Board’s Committee on Investments and Social Responsibility (CISR), which includes Investment Committee representation, in order to explore what such a move could mean for Haverford. The students who initiated this conversation expressed profound concern about the effects of climate change arising from the burning of fossil fuels, and they have challenged the College to engage thoughtfully on how we as an institution and as a community can act within our sphere to mitigate this global threat. As an institution committed to values of ethical concern and social responsibility, the College commends these students for initiating this important conversation. The dialogue has been serious, positive, and informed by the understanding that we must balance needs with ambitions. The CISR’s deliberations on this matter included meetings with the concerned students as well as an open forum with the broader College community, and were supported by research conducted by the College’s investment office. -

Over 100 Global Financial Institutions Are Exiting Coal, with More to Come Every Two Weeks a Bank, Insurer Or Lender Announces New Restrictions on Coal

Tim Buckley 1 Director of Energy Finance Studies, Australasia 27 February 2019 Over 100 Global Financial Institutions Are Exiting Coal, With More to Come Every Two Weeks a Bank, Insurer or Lender Announces New Restrictions on Coal Executive Summary Today, over 100 globally significant financial institutions have divested from thermal coal, including 40% of the top 40 global banks and 20 globally significant insurers. Momentum is building. Since January 2018, a bank or insurer announced their divestment from coal mining and/or coal-fired power plants Global capital is fleeing every month, and a financial institution the coal sector. who had previously announced a divestment/exclusion policy tightened This is no passing fad. up their policy to remove loopholes, every two weeks. In total, 34 coal divestment/restriction policy announcements have been made by globally significant financial institutions since the start of 2018. In the first nine weeks of 2019, there have been five new announcements of banks and insurers divesting from coal. Global capital is fleeing the thermal coal sector. This is no passing fad. Since 2013 more than 100 global financial institutions have made increasingly tight divestment/exclusion policies around thermal coal. When the World Bank Group moved to exit coal in 2013, the ball started rolling. Following, Axa and Allianz become the first global insurers to restrict coal insurance and investment respectively in 2015, and their policies have subsequently been materially enhanced. Next, some 35 export credit agencies (ECA) released a joint statement agreeing to new rules restricting coal power lending. In the same year, the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank trumpeted its global green credentials with the Chairman confirming the Bank was in practice ruling out finance for coal-fired power plants. -

Divest from the Carbon Bubble? Reviewing the Implications and Limitations of Fossil Fuel Divestment for Institutional Investors1

Review of Economics & Finance Submitted on 24/12/2014 Article ID: 1923-7529-2015-02-59-22 Justin Ritchie, and Hadi Dowlatabadi Divest from the Carbon Bubble? Reviewing the Implications and Limitations of Fossil Fuel Divestment for Institutional Investors1 Justin Ritchie (Correspondence author) Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability, University of British Columbia 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada Tel: +1-919-701-9872 E-mail: [email protected] Hadi Dowlatabadi Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability, University of British Columbia 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada Tel: +1-778-863-0103 E-mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://blogs.ubc.ca/dowlatabadi/welcome/ Abstract: Climate change policies that rapidly curtail fossil fuel consumption will lead to structural adjustments in the business operations of the energy industry. Due to an uncertain global climate and energy policy framework, it is difficult to determine the magnitude of fossil energy reserves that could remain unused. This ambiguity has the potential to create losses for investors holding securities associated with any aspects of the fossil fuel industry. Carbon bubble risk is understood as financial exposure to fossil fuel companies that would experience impairments from assets stranded by policy, economics or innovation. A grassroots divestment campaign is pressuring institutions sell their fossil fuel company holdings. By September 2014, investors had responded by pledging to divest US $50 billion of portfolios. Though divestment campaigns are primarily focused on a moral and political rationale, they also regularly frame divesting as a strategy for mitigating stranded asset risk. We review aspects of the divestment movement alongside the context of carbon bubble risk. -

The Carbon Bubble: the Financial Risk of Fossil Fuels and Need for Divestment

EUROPEANGREENPARTY THE CARBON BUBBLE: The financial risk of fossil fuels and need for divestment 2 The 2° target: a minimum consensus which The Carbon Bubble represents economic dynamite 3 The world is agreed: the temperature of the atmosphere must not rise by more than 2°C. However, this means that most oil, gas and coal reserves are valueless. for divestment fossil fuels and need The financial risk of The international community has have on a number of occasions stressed committed itself to an unequivocal target: the urgency of consistent measures if we the Earth’s atmosphere must not warm are to keep the Earth on track towards by more than 2°C by the end of the cen- the 2°C target. tury. At the 2010 UN Climate Conference in Cancún, Mexico, representatives of The 2°C target will not be easy to achieve 194 states committed themselves to this and will only be feasible by determined target. Even the USA and China, who action from the global community. At the never signed the Kyoto Protocol, sup- same time however, climate researchers ported the decision, as do all other major say that 2°C constitutes the borderline greenhouse gas emitters. not between ‘tolerable’ and ‘dangerous’ climate change, but rather between The 2°C target refers to the rise in tem- ‘dangerous’ and ‘very dangerous’ cli- perature relative to pre-industrial levels. mate change. Even with an increase However, as the mean temperature has of ‘only’ 2°C, Arctic ice sheets will melt, already risen by 0.8°C since the 19th and habitats and cultural regions will be Century, the climate must not warm by destroyed. -

Extracting Fossil Fuels from Your Portfoliosm

EXTRACTING FOSSIL FUELS FROM YOUR PORTFOLIOSM: An UPDATED Guide to Personal Divestment and Reinvestment ABOUT THE AUTHORS 350.org is a global network inspiring the world to rise to 100% of Green Century’s profits earned for managing the challenge of the climate crisis. Since its inception in the Green Century Funds belong to the founding group 2008, their online campaigns, grassroots organizing, and of environmental non-profit organizations, the Public mass public actions have been led from the bottom up Interest Research Groups (PIRGs), that started Green by people in 188 countries. Century in 1991. 350 means climate safety. To preserve our planet, Since 2005, Green Century’s Balanced Fund has been scientists tell us we must reduce the amount of CO2 in 100% fossil fuel free; it is an actively managed fund the atmosphere from its current levels of 400 parts per made up of the stocks and bonds of well-managed million to below 350 ppm. 350 is more than a number — companies. The Balanced Fund is almost 50% less it’s a symbol of where we need to head as a planet. carbon intensive than the S&P 500® Index as measured by the international data and analysis firm Trucost.1 The 350 works in a new way — everywhere at once using Green Century Equity Fund, which is also fossil fuel free, online tools to facilitate strategic offline action — under invests in the longest running sustainability index minus the belief that if a global grassroots movement holds the fossil fuel companies in that index. our leaders accountable to the realities of science and principles of justice, we can realize the solutions that For more information, click here or visit www.