Non-Motorized Transportation Network Master Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter IV State Forest Lands

Chapter IV State Forest Lands 4.1 State forest pathways, entry, use, occupancy of certain state forest pathways, designation by director; prohibited conduct. Order 4.1 A person shall not enter, use, or occupy any of the following designated state forest pathways trailheads or parking lot(s) with a motor vehicle, unless a valid Michigan recreation passport has been purchased and affixed to the vehicle: (1) In Alger county: (a) Tyoga. (2) In Alpena county: (a) Besser bell. (b) Chippewa hills. (c) Norway ridge. (d) Ossineke. (e) Wah Wah Tas See. (3) In Antrim county: (a) Jordan valley. (b) Warner creek. (4) In Benzie county: (a) Betsie river. (b) Lake Ann. (c) Platte springs. (5) In Charlevoix county: (a) Spring brook. (6) In Cheboygan county: (a) Inspiration point. (b) Lost tamarack. (c) Wildwood hills. (7) In Chippewa county: (a) Algonquin. (b) Pine bowl. (8) In Clare county: (a) Green pine lake. (9) In Crawford county: (a) Mason tract. (10) In Delta county: (a) Days river. (b) Days river nature trail. (c) Ninga Aki. (11) In Dickinson county: (a) Gene’s pond. (b) Merriman east. (c) West branch. (12) In Gladwin county: (a) Trout lake. (13) In Grand Traverse county: (a) Lost lake. (b) Muncie lake. (c) Sand lakes quiet area. (d) Vasa trail. (14) In Iron county: (a) Lake Mary plains. (15) In Lake county: (a) Pine forest. (b) Pine valley. (c) Sheep ranch. (d) Silver creek. (16) In Luce county: (a) Blind sucker. (b) Bodi lake. (c) Canada lake. (17) In Mackinac county: (a) Big knob/crow lake. (b) Marsh lake. -

Networking Michigan with Trailways

un un F F un F un un F F impacts existing trailways are having in towns like yours all around Michigan. around all yours like towns in having are trailways existing impacts how to start the process, details the extensive benefits of the system and shows you the you shows and system the of benefits extensive the details process, the start to how .. community community your your in in ailway ailway tr tr a a imagine imagine , , Now Now . community your in ailway tr a imagine , Now .. community community your your in in ailway ailway tr tr a a imagine imagine , , Now Now WherWheree CanCan aa MichiganMichigan This brochure tells you tells brochure This Economy Economy Economy Economy residential areas and even industrial areas. industrial even and areas residential Economy TTrrailwayailway TTakeake YYOU?OU? including forests, wetlands, river and lake shorelines, farmlands, shopping areas, shopping farmlands, shorelines, lake and river wetlands, forests, including modes of travel, they take you through the entire range of Michigan environments Michigan of range entire the through you take they travel, of modes This vision of a trailway network truly is a collaborative effort. Passage of the trailways legislation was supported by a broad coalition of agencies and But trailways are more than just a way to get from place to place. Open to many to Open place. to place from get to way a just than more are trailways But ation ation v v Conser Conser ation v Conser ation ation v v Conser Conser organizations. Now, dozens of “trailmakers”—agencies, organizations, communities e. -

2017 Spring 2017 the Need for New Safety Measures to Protect Michigan’S Bicyclists

Lucinda Means Bicycle Advocacy Day On May 24, 2017, Michigan Trails & Greenways Alliance, League of Michigan Bicyclists, People to Educate All Cyclists, Trailblazing in Michigan Trailblazing in Michigan Michigan Mountain Biking Assocaition, and concerned citizens converge at the State Capitol to inform legislators of Spring 2017 Spring 2017 the need for new safety measures to protect Michigan’s bicyclists. Whether riding on the road or riding on a road to get to a trail, tragic incidents can be prevented and most would agree that changes are in order when it comes to 1213 Center Street, Suite D Phone: 517-485-6022 interactions between bicyclists and motorists. This year’s agenda focuses on the following: PO Box 27187 Fax: 517-347-8145 Lansing MI 48909 www.michigantrails.org Michigan Trails and Greenways Alliance is the Michigan Trails Names New Executive Director Bicyclist Safety on Michigan Roads statewide voice for non-motorized trail users, IN THIS ISSUE helping people build, connect and promote trails • Gaining support from lawmakers for SB 0123 and HB 4185, which will establish a state-wide standard of five feet for a healthier and more prosperous Michigan. for safely passing a bicyclist on the roadway. Michigan Trails Names New Executive Director Bob Wilson has been named Executive Director of ““The windows of our minds open up on a trail and take in nature Michigan Trails and Greenways Alliance is Gaining support for SB 0124 and HB 4198, which will require a minimum of one hour of instruction specifically • affiliated with the Michigan Fitness Foundation. Michigan Trails & Greenways Alliance. -

Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund (MNRTF) Grants for 5 Active Or Completed Projects

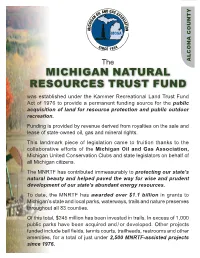

The COUNTY ALCONA MICHIGAN NATURAL RESOURCES TRUST FUND was established under the Kammer Recreational Land Trust Fund Act of 1976 to provide a permanent funding source for the public acquisition of land for resource protection and public outdoor recreation. Funding is provided by revenue derived from royalties on the sale and lease of state-owned oil, gas and mineral rights. This landmark piece of legislation came to fruition thanks to the collaborative efforts of the Michigan Oil and Gas Association, Michigan United Conservation Clubs and state legislators on behalf of all Michigan citizens. The MNRTF has contributed immeasurably to protecting our state’s natural beauty and helped paved the way for wise and prudent development of our state’s abundant energy resources. To date, the MNRTF has awarded over $1.1 billion in grants to Michigan’s state and local parks, waterways, trails and nature preserves throughout all 83 counties. Of this total, $245 million has been invested in trails. In excess of 1,000 public parks have been acquired and / or developed. Other projects funded include ball fields, tennis courts, trailheads, restrooms and other amenities, for a total of just under 2,500 MNRTF-assisted projects since 1976. ALCONA COUNTY Alcona County has received $644,100 in Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund (MNRTF) grants for 5 active or completed projects. Alcona County Active or Completed MNRTF projects ALCONA TOWNSHIP • Park Improvements: $108,700 CALEDONIA TOWNSHIP • Hubbard Lake North End Park Development: $245,400 DNR – PARKS & RECREATION DIVISION • South Bay-Hubbard Lake: $145,000 DNR – WILDLIFE DIVISION • Hubbard Lake Wetlands: $130,000 VILLAGE OF LINCOLN • Brownlee Lake Boat Launch: $15,000 ALGER COUNTY ALGER The MICHIGAN NATURAL RESOURCES TRUST FUND was established under the Kammer Recreational Land Trust Fund Act of 1976 to provide a permanent funding source for the public acquisition of land for resource protection and public outdoor recreation. -

Search Results Recreational Trails Program Project Database

Search Results Recreational Trails Program Project Database Your search for projects in State: MI, Total Results : 316 State Project Trail Name Project Name Description Cong. District(s) County(s) RTP Funds Other Funds Total Funds Year MI 2016 Bergland-Sidnaw Trail Bergland-Sidnaw Trail Bergland-Sidnaw Trail bridge over the South 1 Ontonagon $0 Unknown $0 Bridge over the South Branch Ontonagon River Branch Ontonagon River MI 2016 Higgins Lake Trail Higgins Lake Trail Unspecified/Unidentifiable 4 Roscommon $0 Unknown $0 MI 2016 Alpena to Hillman Trail Alpena to Hillman Trail Bridges and Culverts 1 Alpena $0 Unknown $0 MI 2016 Musketawa Trail Musketawa Trail Connector Musketawa Trail Connector 2 Muskegon $0 Unknown $0 MI 2016 Baraga-Arnheim Rail-Trail Baraga-Arnheim Rail-Trail Baraga-Arnheim Trail culvert renovation 1 Baraga $0 Unknown $0 MI 2016 Kalkaska Mt. Bike Trail Kalkaska Mt. Bike Trail Kalkaska Mt. Bike Trail 1 Kalkaska $0 Unknown $0 MI 2016 Michigan State Park Trail Engineering, Design, and Trailway program engineering and design 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, Statewide $0 Unknown $0 System Cost Estimating 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 MI 2016 Michigan State Park Trail Partnership Grants Trailway program partnership grants 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, Statewide $0 Unknown $0 System 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 MI 2016 Iron Belle Trail Iron Belle Trail Environmental investigation for purchase of 5 Genesee $0 Unknown $0 Iron Belle Trail corridor MI 2016 State Park Linear Trail O&M State Park Linear Trail O&M State park linear trail operation and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, Statewide $0 Unknown $0 Projects Projects maintenance 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 MI 2016 Winter Recreation Trails Maintenance Pathway crossing, ski groom and parking lot 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, Statewide $0 Unknown $0 maintenance 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 MI 2016 Michigan State Park Trail Pathway Signage Upgrades Pathway Signage Upgrades 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, Statewide $0 Unknown $0 System 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 State Project Trail Name Project Name Description Cong. -

2008 Trail Directory 9.Pdf

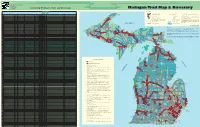

Michigan Trails and Greenways Alliance PO Box 27187 1213 Center St Ste D Lansing MI 48909 (517) 485-6022 Connecting Michigan’s Trails and Greenways www.michigantrails .org MichiganMichigan TrailTrail MapMap && DirectoryDirectory Legend: Detroit Place Name Copyright 2008 Michigan Trails and Greenways ID NAME OF TRAIL MILES SURFACE INFORMATION CONTACT PHONE SnowmobileHorse ORV Notes ENDPOINTS WEBSITE Open Multi-Use Trails UPPER PENINSULA Alliance 41 KEWEENAW 1 State Line Trail 102 unimproved MDNR Forest Management Division (906) 353-6651 Wakefield, Stager www.michigantrails.org/map North County Trail Wayne County Name This map may not be copied or reproduced by any means, 2 Watersmeet/Land O’Lakes Trail 9 unimproved MDNR Forest Management Division (906) 353-6651 Land O’Lakes, Watersmeet www.michigantrails.org/map or in any manner without the written permission of Michigan Calumet 3 Bergland to Sidnaw Rail Trail 45 unimproved MDNR Forest Management Division (906) 353-6651 Bergland, Sidnaw www.michigantrails.org/map 5 14 Trail ID - See Trail Table Highways Trails and Greenways Alliance 4 Bill Nicholls Trail 40 unimproved MDNR Forest Management Division (906) 353-6651 Houghton, Adventure Mountain www.michigantrails.org/map Hancock 6 5 Hancock/Calumet Trail aka (Jack Stevens) 13.5 unimproved MDNR Forest Management Division (906) 353-6651 Hancock, Calumet www.michigantrails.org/map Boundary Between Adjacent Trails Other Primary Roads Should you find any inaccuracies or omissions on this map, Houghton we would appreciate hearing about them. Please -

Chapter IV State Forest Lands

Chapter IV State Forest Lands 4.1 State forest pathways, entry, use, occupancy of certain state forest pathways, designation by director; prohibited conduct. Order 4.1 A person shall not enter, use, or occupy any of the following designated state forest pathways trailheads or parking lot(s) with a motor vehicle, unless a valid Michigan recreation passport has been purchased and affixed to the vehicle: (1) In Alger county: (a) Tyoga. (2) In Alpena county: (a) Besser bell. (b) Chippewa hills. (c) Norway ridge. (d) Ossineke. (e) Wah Wah Tas See. (3) In Antrim county: (a) Jordan valley. (b) Warner creek. (4) In Benzie county: (a) Betsie river. (b) Lake Ann. (c) Platte springs. (5) In Charlevoix county: (a) Spring brook. (6) In Cheboygan county: (a) Inspiration point. (b) Lost tamarack. (c) Wildwood hills. (7) In Chippewa county: (a) Algonquin. (b) Pine bowl. (8) In Clare county: (a) Green pine lake. (9) In Crawford county: (a) Mason tract. (10) In Delta county: (a) Days river. (b) Days river nature trail. (c) Ninga Aki. (11) In Dickinson county: (a) Gene’s pond. (b) Merriman east. (c) West branch. (12) In Gladwin county: (a) Trout lake. (13) In Grand Traverse county: (a) Lost lake. (b) Muncie lake. (c) Sand lakes quiet area. (d) Vasa trail. (14) In Iron county: (a) Lake Mary plains. (15) In Lake county: (a) Pine forest. (b) Pine valley. (c) Sheep ranch. (d) Silver creek. (16) In Luce county: (a) Blind sucker. (b) Bodi lake. (c) Canada lake. (17) In Mackinac county: (a) Big knob/crow lake. (b) Marsh lake. -

Michigan Trail

41 ICONS KEY Paved Trail Crushed Stone Unimproved Road Portions Boardwalk Horses Snowmobiles ORV * Indicates companion notes regarding the trail, which may be found here: http://bit.ly/traildirectorynotes. MICHIGAN MULTI-USE TRAIL DIRECTORY & MAP ID NAME OF TRAIL MILES ENDPOINTS ID NAME OF TRAIL MILES ENDPOINTS Go for a bike ride, run or hike on Michigan's multi-use trails, stretching more than 2,100 miles across the state. 1 North Western State Trail 32 Mackinaw City, Petoskey 51 Ionia River Trail 4 City of Ionia This directory features trails over 3.5 miles, though there are many more across the state with less mileage. Trails http://bitly.com/nwstrail http://bit.ly/IRtrail Map Key Multi-Use Trails 2 Burt Lake Trail 5.5 Maple Bay Rd., Topinabee 52 *Fred Meijer Clinton-Ionia-Shiawassee Trail 42 Prairie Creek Bridge Ionia, Smith Rd., Owosso in the Lower Peninsula are mostly surfaced in asphalt, or crushed stone (granite/limestone). Trails in the Upper http://bit.ly/Blaketrail http://bit.ly/FMCIStrail Peninsula include some unimproved rail-trails (dirt/grass/gravel/ballast) as well as linear mountain bike trails 24 Trail ID - See Trail Table 3 *North Central State Trail 62 Mackinaw City, Gaylord 53 Portland Riverwalk 15 Portland High School -Cutler Rd. http://bitly.com/ncstrail http://bit.ly/Prtrail (dirt) through forests and parks. State parks are included as additional places to bike and hike, and many offer Connection Between Trails 4 North Eastern State Trail 71 Cheboygan, Alpena camping accommodations. This map may be downloaded from www.michigantrails.org/trails. -

Michigan Trails Advisory Workgroup (Mtac)

MICHIGAN TRAILS ADVISORY WORKGROUP (MTAC) Meeting Minutes Location: Virtual meeting Date: April 8, 2021 6-8 p.m. Welcome – Roll Call PRESENT FOR THE MICHIGAN TRAILS ADVISORY COUNCIL: • Bob Wilson, Chairperson • Jason Jones • Michael Maves • Mark Losey • Mary Van Dorp (absent) • James Kelts • Jessi Adler • Jenny Cook (absent) • Kenneth Hopper • Richard Williamson (absent) • Donald Kauppi PRESENT FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES (DEPARTMENT) STAFF • Paul Yauk, Jessica Holley, Annalisa Centofanti, Scott Slavin, Ron Yesney, Chris Knights, Michael Morrison, Kristen Bennett, Kristen Thrall (USFS), Danielle Zubek, Roger Storm, Ron Olson, Scott Pratt, Dakota Hewlett, Jeff Kakuk, Paul Gaberdiel, Gary Jones, Thomas Bissett, Thomas Seablom, Paige Perry, Ron Yesney, Kristin Phillips Bob Wilson started the meeting with an open statement. Bob welcomed four (4) new members to the council (Jason Jones, Michael Maves, Mark Losey, and Mary Van Dorp). An important role to fill this year will be to work with the Department of Natural Resources (DNR), along with Public Sector Consultants (PSC) to develop a master trail plan. The group has already held meetings, working towards objectives, goals, and action items, and are now working on refining those items. We are getting close to a point where MTAC will be formerly adopting a recommendation from the DNR. Bob expressed a “shout out” to all the groups working on this program. Also, a thank you to the DNR for working under the COVID-19 circumstances in the past year. Meeting minutes ACTION ITEMS Bob Wilson made a motion to approve Sept. 23, 2020 meeting minutes. Jim Kelts and Don Kauppi approved, with all in favor. -

The DALMAC Fund - Grants by Year

The DALMAC Fund - Grants By Year The DALMAC Fund was established in 1975 by the DALMAC Agreement between Dick Allen and the Tri-County Bicycle Association (TCBA) of Lansing. DALMAC stand for Dick Allen Lansing to Mac kinaw. Included in the DALMAC Agreement was the creation of the DALMAC Fund. The DALMAC Fund was established to promote bicycling in Michigan. Dick Allen’s original purpose for riding from Lansing to Mackinaw went far beyond just a recreational ride. He wanted to bring the fun and health benefits of bicycling to all who would participate and advance Michigan’s prospects for active, outdoor tourism on a bicycle. The first DALMAC Fund use was in 1976. Funds were used to buy a bicycle for St. Vincent Children's Home in Lansing. The first significant expenditure of DALMAC Fund money started in April, 1978, when TCBA stated a statewide newsletter, initially called the Michigan League. The publication’s initial mailing list was made up of DALMAC riders, TCBA members, and members of the League of American Wheelmen in Michigan. The League of American Wheelmen is now called the League of American Bicyclists. The publication was renamed the Michigan Bicyclist in 1981. The Michigan Bicyclist newsletter was transferred to the League of Michigan Bicyclists in 1983 and officially became their newsletter. The DALMAC Fund stopped financing the Michigan Bicyclist newsletter when it because the League of Michigan Bicyclists’ newsletter. 1985 marked the creation of the DALMAC Fund committee. Systematic grant records begin with the Committee’s creation. The committee was formed to more effectively dispense money, which had been growing rapidly since 1981 because of DALMAC's increased ridership under the management of Events Director Kim Wilcox. -

MEET ROGER STORM the Johnny Appleseed of Michigan’S Rails-To-Trails Movement by TOM RADEMACHER

TRAILBLAZER Roger Storm enjoys a sunny autumn ride on the Mike Levine Lakelands Trail, one of his first rail-trail acquisitions. MEET ROGER STORM The Johnny Appleseed of Michigan’s Rails-to-Trails Movement BY TOM RADEMACHER or someone with a last name that history may one day look back on and Born in the summer of 1952, Storm conjures up images of menacing proclaim him as “The Johnny Appleseed of remembers himself as an introvert, though weather, Roger E. Storm is instead the Michigan Rails-to-Trails Movement.” his older sister talked him into trying out and the kind of person who gets things Because — and there is little room for securing the part of 10-year-old Winthrop done by leaning on subtle persua- argument — if it weren’t for Roger Storm, Paroo, the adorable lisping youngster who Fsion and the Socratic method. it’s likely there would be far fewer trails steals several scenes in “The Music Man.” In other words, more like the famous throughout the state. Storm had a natural lisp at the time, so persona imbued in his fi rst name. “When it comes to solving issues, he’s much so that he underwent speech therapy “It’s funny,” he says, “but just recently like a dog on a bone,” says Nancy Krupiarz, for it. He laughs: “I could probably still sing here at work someone referred to me as former executive director of the Michigan all the words to “Gary, Indiana.” ‘Mr. Rogers,’ and that was after my time, so Trails & Greenways Coalition. -

2017 Summer 2017

2017-2020 Board Member Nominees In keeping with the mission of the Michigan Trails & Greenways Alliance, we seek Board members who demonstrate and confirm the vision for an interconnected statewide system of multi-use trails, preserve the integrity of the organization and Trailblazing in Michigan Trailblazing in Michigan provide financial sustainability. Summer 2017 Summer 2017 1213 Center Street, Suite D Phone: 517-485-6022 The following nominees are running for a three year term beginning January 1, PO Box 27187 Fax: 517-347-8145 2018 through December 30, 2020. Lansing MI 48909 www.michigantrails.org Michigan Trails and Greenways Alliance is the Connecting Michigan with the Iron Belle Trail statewide voice for non-motorized trail users, Governor Rick Snyder Harry Burkholder IN THIS ISSUE helping people build, connect and promote trails Harry was appointed as the Executive Director of Land Information Access Association (LIAA) in October 2015, following 11 for a healthier and more prosperous Michigan. When people think of Michigan, they most likely think of the Comeback State, the “The nation behaves well if it treats the natural resources years on LIAA’s community planning team. Working with the Board of Directors, Harry helps to set the strategic direction and automotive capital of the world, and the phrase Pure Michigan. What they may not Connecting Michigan with the Iron Belle Trail as assets which it must turn over to the next generation policies for the organization and leads the organization in corporate planning, project management, program design and Michigan Trails and Greenways Alliance is realize is that we can also be thought of as the Trails State.