Gender, Water and Livelihoods in Mseleni: a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

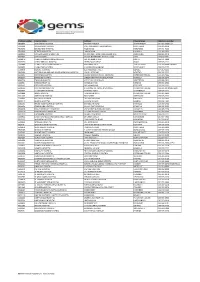

Uthukela Health Districts Know Your Vaccination Sites

UTHUKELA HEALTH DISTRICTS KNOW YOUR VACCINATION SITES :WEEK 09 Aug – 15 Aug 2021 SUB-DISTRC FACILITY/SITE WARD ADDRESS OPERATING DAYS OPERATING HOURS T Inkosi Thusong Hall 14 Next to old Mbabazane 10-13 AUG 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalel Ntabamhlope Municipal offices e Inkosi Estcourt Hospital South 23 KNOWNo YOUR 1 Old VACCINATION Main Road SITES 9-15 AUG 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalel Wing nurses home e Inkosi Wembezi Hall 9 VQ Section 10-13 AUG 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalel e UTHUKELA HEALTH DISTRICTS KNOW YOUR VACCINATION SITES :WEEK 09 Aug – 15 Aug 2021 SUB-DISTRC FACILITY/SITE WARD ADDRESS OPERATING DAYS OPERATING HOURS T Okhahlamba Maswazini community hall 14 Near tribal court 8 /8/2021 08:00 – 16:00 Okhahlamba Bergville sports complex 11 Golf street , Bergville, 8,9 ,11,12 ,13 and 08:00 – 16:00 14/8/2021 KNOW YOUR VACCINATION SITES Okhahlamba Rooihoek community hall 13 Near Rooihoek primary school 9 and 10 /8/2021 08:00 – 16:00 Okhahlamba Emmaus Hospital 2 Cathedral Peak Road 9 ,10,11,12 ,13 and 08:00 – 16:00 14/8/2021 Okhahlamba Khethani hall/ Winterton 1 Near KwaDesayi , Supermarket 10/8/2021 08:00 – 16:00 Okhahlamba Jolly Bar community hall ( 8 Near Mafu High School 11,12 and 13/08/2021 08:00 – 16:00 Moyeni) Okhahlamba Tabhane High School 4 Near Tabhane Community hall 14/8/2021 08:00 – 16:00 UTHUKELA HEALTH DISTRICTS KNOW YOUR VACCINATION SITES :WEEK 09 Aug – 15 Aug 2021 SUB-DISTRCT FACILITY/SITE WARD ADDRESS OPERATING DAYS OPERATING HOURS Alfred Ladysmith Nurses 12 KNOW36 YOUR Malcom VACCINATION road SITES 09 - 15 August -

Kwazulu-Natal Province Facility, Sub-District and District

KWAZULU-NATAL PROVINCE FACILITY, SUB-DISTRICT AND DISTRICT Facility Posts Period Field of Study Province District Sub-District Facility 2017 Audiologist kz KwaZulu-Natal Province kz Amajuba District Municipality kz Dannhauser Local Municipality kz Dannhauser CHC 1 kz Dannhauser Local Municipality Total 1 kz Newcastle Local Municipality kz Madadeni Hospital 1 kz Newcastle Local Municipality Total 1 kz Amajuba District Municipality Total 2 kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Sub kz Hlengisizwe CHC 1 kz Tongaat CHC 1 kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Sub Total 2 kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Total 2 kz Harry Gwala District Municipality kz Greater Kokstad Local Municipality kz East Griqualand and Usher Memorial Hospital 1 kz Greater Kokstad Local Municipality Total 1 kz Ubuhlebezwe Local Municipality kz Christ the King Hospital 1 kz Ubuhlebezwe Local Municipality Total 1 kz Umzimkhulu Local Municipality kz Rietvlei Hospital 1 kz St Margaret's TB MDR Hospital 1 kz Umzimkhulu Local Municipality Total 2 kz Harry Gwala District Municipality Total 4 kz iLembe District Municipality kz Mandeni Local Municipality kz Sundumbili CHC 1 kz Mandeni Local Municipality Total 1 kz Ndwedwe Local Municipality kz Montebello Hospital 1 kz Ndwedwe Local Municipality Total 1 kz iLembe District Municipality Total 2 kz Ugu District Municipality kz Hibiscus Coast Local Municipality kz Gamalakhe CHC 1 kz Hibiscus Coast Local Municipality Total 1 kz Ugu District Municipality Total 1 kz uMgungundlovu District Municipality -

Submitted in Accordance with the Requirement for the Degree of in the Department of Atthe

TOWARDS CULTURE CARE NURSING EDUCATION: A STUDY OF T.G. MASHABA'S TRANSCULTURAL THEMES BY THOKOZANIP.MHLONGO submitted in accordance with the requirement for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the Department of ADVANCED NURSING SCIENCES atthe UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: PROFESSOR HIL BRINK JOINT-PROMOTER: PROFESSOR JB HLONGWANE JUNE 1998 ii DECLARATION I declare that TOWARDS CULTURE CARE NURSING EDUCATION: A STUDY OF T.G. MASHABA'S TRANSCULTURAL THEMES is my work and all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. Thokozani P. Mh iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am eternally grateful to the Almighty God for giving me life and the ability to pursue my academic dream. I wish to extend my sincere gratitude and appreciation to Professors HIL Brink and JB Hlongwane, my promoters, for their wise guidance and consistent encouragement. If it was not for their help, this thesis would still have been in the form of notes. Nikhule nize nikhokhobe! I am greatly indebted to my beloved relatives for sustaining my zeal and to my beloved family - [bonke oMakhedama nabo bonke abaNtwana - abaseZulwini (Odidini), kwaPhindangene, naseNkombabantu] -for their love, understanding and support. All my friends - at UNISA:Doctor, Rua, Professors CT and DBZ, Ursula, Olive, Nita, Dirk, Sonya, Mavis, Anneli, Margo, Susan, Sarie, Kathy, Laetitia, Olga; UNIZUL: ~ursing Department staff, especially Dr Zungu and Mrs Mhlongo; UNITRA: Sizwe, Sokhela, Thembeka; KZN Nursing Department staff: Lulu, Mrs. Memela, Hlongwane, Nxumalo, Moleko, Cele; and IOWA, USA: Paula, Meridean, Toni, Pat, Mary, Kathleen, Keela, Fran, Colleen, Marita, and Pam - have been more than I expected. -

Practice Number Hospital Name

Practice number Hospital name Address Physical town Telephone number 5600847 ADDINGTON HOSPITAL ERSKINE TERRACE SOUTH BEACH 031-327-2380/1/2 5604303 APPELBOSCH HOSPITAL PAST APPELBOSCH SUPERMARKET MONTEBELO 033-395-2270 5603838 BENEDICTINE HOSPITAL MAIN ROAD NONGOMA 035-831-7000 5603846 BETHESDA HOSPITAL , MAIN ROAD UBOMBO 033-395-2922 5603854 CATHERINE BOOTH HOSPITAL 11 KMS PAST, AMATIKULU SUGAR MILL AMATIKULU 033-395-2270 5603862 CEZA HOSPITAL 20 KMS NORTH KING DINIZULU H/W CEZA 035-832-0001 5603870 CHARLES JOHNSON MEMORIAL HSP LOT 92, HLUBI STREET NQUTU 034-271-1900 5603730 CHRIST THE KING HOSPITAL PETER HAUFF DRIVE IXOPO 033-395-2922 5603889 CHURCH OF SCOTLAND HOSPITAL MALOMINI AREA TUGELA FERRY 033-793-0004 ext 4042 5600855 CLAIRWOOD HOSPITAL 1 HIGGINSON HIGHWAY WOODLANDS 033-395-2922 5600979 DUNDEE HOSPITAL 121 MCKENZIE STREET DUNDEE 034-212-1111 5602009 EAST GRIQUALAND AND USHER MEMORIAL HOSPITAL CNR ELLIOT ROAD KOKSTAD 033-395-2922 5600871 EDENDALE HOSPITAL MOSES MABIJIDA ROAD, EDENDALE PIETERMARITZBURG 033-395-4026 5603897 EKHOMBE HOSPITAL DIRECTIONS FROM NKANDLA HOSP NKANDLA 033-395-2270 5603749 EMMAUS HOSPITAL CATHEDRAL PEAK ROAD WINTERTON 033-395-2922 5600987 ESHOWE HOSPITAL KANGELA STREET ESHOWE 033-395-2922 5600995 ESTCOURT HOSPITAL OLD MAIN ROAD ESTCOURT 033-395-2922 5602130 FORT NAPIER HOSPITAL 1 DEVONSHIRE PLACE, NAPIERVILLE PIETERMARITZBURG 033-395-2270/345-4221 5600863 G J CROOKE'S HOSPITAL HOSPITAL ROAD SCOTTBURGH 033-395-2922 5600898 GREYS HOSPITAL TOWNBUSH ROAD PIETERMARITZBURG 033-395-2922 5601002 GREYTOWN HOSPITAL -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report

VOLUME THREE Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction to Regional Profiles ........ 1 Appendix: National Chronology......................... 12 Chapter 2 REGIONAL PROFILE: Eastern Cape ..................................................... 34 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Eastern Cape........................................................... 150 Chapter 3 REGIONAL PROFILE: Natal and KwaZulu ........................................ 155 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in Natal, KwaZulu and the Orange Free State... 324 Chapter 4 REGIONAL PROFILE: Orange Free State.......................................... 329 Chapter 5 REGIONAL PROFILE: Western Cape.................................................... 390 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Western Cape ......................................................... 523 Chapter 6 REGIONAL PROFILE: Transvaal .............................................................. 528 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Transvaal ...................................................... -

The Feasibility of Establishing a Trading Centre at Mseleni

The Feasibility of Establishing A Trading Centre at Mseleni Consolidated Report: Situational Analysis & Final Report July 2010 KwaZulu-Natal Department of Economic Development and Tourism Report prepared by: The Feasibility of Establishing a Trading Centre at Mseleni Consolidated Report: Situational Analysis & Final Report – Report prepared by Graham Muller Associates TABLE OF CONTENTS Situational Analysis ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Project alignment with the uMhlabuyalingana Local Municipality IDP and the LED strategy ...................... 5 Overview of municipality as per IDP .............................................................................................................. 7 Assessment of the LED environment ............................................................................................................. 8 Assessment of the Proposed Site & Alternatives......................................................................................... 10 Retail catchment assessment ...................................................................................................................... 13 Demographics of the catchment area ......................................................................................................... 17 Assessment -

Kosi Forest Lodge Directions

Updated: April 2011 Directions to Kosi Forest Lodge Recommended route from Johannesburg : (8 hours) Head to Piet Retief on the N2, pass through Pongola and proceed south towards Hluhluwe (approximately 113km from Pongola). Turn left into the town of Hluhluwe (approx. 4kms) and follow the instructions below " Recommended route from Durban ". *** Alternate Route from Johannesburg : Head to Piet Retief and Pongola on the N2 and proceed south towards Mkuze. Approximately 45km from Pongola and 10km before Mkuze turn left towards Jozini. On leaving Jozini take a left turn towards the “Coastal Forest Reserve and KwaNgwanase” (signposted), ensuring that you are proceeding over the Pongola dam wall. After 45km at a T-junction turn right towards “KwaNgwanase”. Proceed for another 47 km past Tembe Elephant Park towards the town of Manguzi (KwaNgwanase). Please note that this route often has cattle wandering across it, some of the signs have fallen down and so caution and slower driving speeds are necessary. Also particularly around the area of Tembe Elephant Park, the road has quite a few large potholes which have caused damage to some cars. Although this route may appear shorter in distance, it takes almost as much time as the Hluhluwe Recommended Route above, but without all the hazards! From Durban City: (5 hours) From Durban, proceed on the N2 North out of Durban bypassing Richards Bay, Empangeni and Mtubatuba and head towards the town of Hluhluwe. Turn off the N2 towards Hluhluwe, proceeding through the town until you reach the last traffic circle. Turn left towards Mbazwane/Sodwana Bay and proceed for 0.7 km and turn right again towards Sodwana Bay/Mbazwane. -

Northern Kwazulu-Natal)

Perspectives on sustainable ecotourism with specific reference to the Ingwavuma district (northern KwaZulu-Natal) by Michael Andrew Mearns Mini-dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium in Development Studies in the Faculty of Arts at the Rand Afrikaans University Supervisor: Prof. C.J. Maritz Associate supervisor: Dr. J.M. Meeuwis December 1999 The Ingwavuma district in Maputaland is an area where people still walk miles to called water and firewood; where children are taught under a tree; where a cow is slaughtered beside the mad, and an hour later the meat is sold under a tree in an outdoor butchery. A place where one can hear the beating of far off drums. The people are very poor, but they are always friendly and smiling. At night the area has an eerie silence, except for a cock crowing at a distant homestead or the desperate cry of a bushbaby. The sky is still filled with stars. During the day the area is hot and as an outsider one soon looses the anxiety of the city. One catches oneself slowing down from the rush, taking a different look at things. One starts noticing the difference; struck by the isolation and the quiet. The quietness one can only get in Africa. The people are friendly and relaxed, causing a city dweller to become sceptic. Why is it so different? ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend a word of thanks and appreciation to all of the people who contributed towards the completion of this study. A special word of thanks to the following: Prof. -

District Health Plan 2015/2016 : Umkhanyakude

DISTRICT HEALTH PLAN 2015/2016 UMKHANYAKUDE DISTRICT KWAZULU-NATAL [UMKHANYAKUDE] DISTRICT HEALTH PLAN 2015/16 1. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to District Health Management Team and Program Managers who contributed to development of the DHP 2015/16. The support from the Provincial Planning Unit during the development of this document was of great value. The M&E Team worked tirelessly in co-ordination of the document so that it meets the legislative mandates of the department. The team went beyond their call of duty to ensure that the document is meaningful. The efforts of the district Data Management team are acknowledged as they continued to verify data that was submitted. A special word of appreciation goes to Dr. Immelman who was able to carry dual roles and participated fully in this exercise. Our word of gratitude also goes to the supporting partner (MatCH) who gave technical support to the team. Their contribution kept the team focused to the entire process. 2 | Page [UMKHANYAKUDE] DISTRICT HEALTH PLAN 2015/16 2. OFFICIAL SIGN OFF It is hereby certified that this District Health Plan: Was developed by the district management team of Umkhanyakude Health District with the technical support from the provincial district development directorate and the strategic planning unit. Was prepared in line with the current Strategic Plan and Annual Performance Plan of the Department of Health of KZN 3 | Page [UMKHANYAKUDE] DISTRICT HEALTH PLAN 2015/16 3. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. 2 2. OFFICIAL SIGN OFF ...................................................................................................... 3 3. TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................. 4 4. LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................... -

Kwazulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal Municipality Ward Voting District Voting Station Name Latitude Longitude Address KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830014 INDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.99047 29.45013 NEXT NDAWANA SENIOR SECONDARY ELUSUTHU VILLAGE, NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830025 MANGENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.06311 29.53322 MANGENI VILLAGE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830081 DELAMZI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09754 29.58091 DELAMUZI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830799 LUKHASINI PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.07072 29.60652 ELUKHASINI LUKHASINI A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830878 TSAWULE JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.05437 29.47796 TSAWULE TSAWULE UMZIMKHULU RURAL KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830889 ST PATRIC JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.07164 29.56811 KHAYEKA KHAYEKA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830890 MGANU JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -29.98561 29.47094 NGWAGWANE VILLAGE NGWAGWANE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11831497 NDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.98091 29.435 NEXT TO WESSEL CHURCH MPOPHOMENI LOCATION ,NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKHULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830058 CORINTH JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09861 29.72274 CORINTH LOC UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830069 ENGWAQA JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.13608 29.65713 ENGWAQA LOC ENGWAQA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830867 NYANISWENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.11541 29.67829 ENYANISWENI VILLAGE NYANISWENI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830913 EDGERTON PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.10827 29.6547 EDGERTON EDGETON UMZIMKHULU -

Audit of Failure Rate of Sulfadoxine/Pyrimethamine

Auditof failurerate of sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine combinedwith chloroquine to treatfalciparum malariaat singlefourteen-day follow-up. VaughanWilliams,CH Summary-i\ BSc,MBBS, DCH, Objective. MFamMed(Natal) To assessthe failure rate of the presentfirst line treatmentregime for MosvoldHospital, lngwavuma, uncomplicatedfalciparum malaria of sulfadoxine/pyrimethaminecombined KwaZulu-Natal,South Africa with chloroquine. Memberof Subcommitteefor Design. Chemoprophylaxisand Therapy A before-afterstudyl of the NationalMalariaAdvisory Group Setting. La Cock, C Ndumo Clinic,Ingwavuma District, South Africa, October 2000 StudyGroup.55 patientspresenting to Ndumo clinicwith uncomplicated MedicalTechnologist, KwaZulu- malariaand malariatrophozoites visible on thin film. NatalLaboratory Services at Department of ::".i..":d Main outcome measures: Health,Jozini Trophozoitecount on thick film at day14. Henry, GFf Results. MBBS,DRCOG, MRCGP l5 out of 37 patientswho returnedfor follow-upstill had trophozoites MosvoldHospital, Ingwavuma on thick film.Symptoms of most patientsat day0 and day l4 were mild, Ross,AJ parasitecounts before and after treatment were low, and trophozoites MB,ChB,DCh, MFamMed were atypical. (MEDUNSA) Conclusions. MedicalSuperintendent, There appearsto be an unacceptablyhigh day 14 failure rate with the MosvoldHospital, Ingwavuma combinationof sulfadoxine/pyrimethamineand chloroguine.Themildness Correspondence to: of symptoms,low parasite counts and atypicaltrophozoites suggest VaughanWilliams immunityto falciparummalaria amongst the -

Teaching Non Zulu-Speaking Medical Students to Communicate with Zulu-Speaking Patients in the Out-Patients' Department

TEACHING NON ZULU-SPEAKING MEDICAL STUDENTS . TO COMMUNICATE WITH ZULU-SPEAKING PATIENTS .. , , IN THE OUT-PATIENTS' DEPARTMENT THE FORMULATION AND RATIONALE OF A ZULU FOR SPECIFIC PURPOSES (ZSP) SECOND LANGUAGE SYLLABUS FOR THE MEDICAL CONSULTATION SETTING BY JACQUELlNE ANNE COCKERILL A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Human Sciences in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts, in the Department oflsiZulu, University of Natal, Durban. Supervisor: Mrs Beverley Muller December 2002 . ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: I would like to acknowledge, with thanks, the assistance of the following persons: ~ Mrs Beverley Muller, for guidance and encouragement and for the many hours she devoted to the supervision of this thesis. ~ Or Chris Ellis, Professor Sihawukele Ngubane and Or Thenjiwe Magwaza for their help in providing cultural information relating to Zulu perspectives on health and illness in the context of the medical consultation. ~ Mr Francis Zungu for transcribing and translating twelve of the taped consultations observed during my field-work in the hospitals. ~ The doctors (listed in Appendix D) who agreed to be interviewed by me or who allowed me to sit in on their consultations and observe their dealings with patients. ~ The medical superintendents at McCords Hospital, Bethesda Hospital, Mseleni Hospital, Manguzi Hospital and Mosvold Hospital who facilitated my research in the hospitals. ~ Red Cross and the staff responsible for their "flying doctor" service, for transporting me from Durban to the hospitals in northern Kwa-Zulu Natal. ~ The syllabus designers and administrative staff at the University of Natal Medical School, particularly Professor Michelle Mclean, Mrs Jackie Van Wyk and Ms Veena Singaram, for their assistance in the planning and implementation of the first one-year introductory medical Zulu course introduced at the Medical School in 2001.