Christine Camp Interviewer: Ronald J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Parts That Were Left out of the Kennedy Book

"This war is, I believe, a war for civilization." —Francis Cardinal Spellman ■-•-':.0.7y3 • 1.1%....0. 4,10 14'.0'. f.A.- 444 The Parts That Were Left Out of the Kennedy Book •■••• ■••■••■••■■ An executive in the publishing industry, who obviously The senior Kennedy had predicted that Germany would must remain anonymous, has nuole available to the Realist defeat England and he therefore urged President a photostatic copy of the. original manuscript of William Manchester's book, The Death of a President. Franklin D. Roosevelt to withhold aid. Those passuges which are printed here were marked for Now Johnson found himself fighting pragmatism with deletion months before Harper & Row sold the serialization pragmatism. It didn't work; he lost the nomination. rights to Look magazine; hence they do not appear even Ironically, the vicissitudes of regional bloc voting in the so-railed "complete" version published by the Ger- man magazine, Stern. forced Kennedy into selecting Johnson as his running mate. Jack 'rationalized the practicality of the situation. but Jackie was constitutionally unable to forgive John- At the Democratic National Convention in the sum- son. Her attitude toward him always remained one of mer of 1960 Los Angeles was the scene of a political controlled paroxysm. visitation of the alleged sins of the father upon the son. Lyndon Johnson found himself battling for the presi- dential nomination with a young, handsome, charming It was common knowledge in Washington social cir- and witty adversary, John F. Kennedy. cles that the Chief Executive was something of a ladies' The Texan in his understandable anxiety degenerated man. -

Item 068.Pdf

TIMETHE WEEKLY NEWSMAGAZINE Dec. 23, 1966 Vol. 88, No. 26 THE NATION scenes for months as rumors buzzed in tion. In his original version, at least, THE PRESIDENCY Washington and New York about the Manchester told how the Kennedy con- Battle of the Book book's incendiary contents, and about tingent arrived at Dallas' Love Field "I have to try, We might lose this, the problems between the Kennedys with the President's body and was "dis- but I have to try. I can't lose all that and the author and publisher. But the mayed" to find that Johnson's party had I've tried to protect for these years. FE4 book has done far more than merely moved in to Air Force One. Johnson have to do what is necessary. We have upset the Kennedys. It has set many himself was already ensconced in the to sue." New Frontiersmen against one another, President's quarters. Moreover, the ac- With those anguished words to close caused the author to become ill and count portrayed L.B.J.'s aides as shocked friends last week, Jacqueline Kennedy brought turmoil to the publishing world, and saddened but scarcely able to dis- set in motion the biggest brouhaha over guise their satisfaction at finally tak- a book that the nation has ever known. ing command. The book was no ordinary one: it was So great was the tension aboard the William Manchester's The Death of a plane during the flight back to Washing- President, which has been awaited as ton, according to Manchester, that after the authoritative account of the assas- Air Force One landed at the capital, sination of John F. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE on Taste and Nation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE On Taste and Nation Dissertation Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degrees of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Visual Studies by Anna Therese Kryczka Dissertation Committee Chancellor’s Professor Cécile Whiting, Chair Professor Catherine Liu Associate Professor Victoria E. Johnson 2016 © 2016 Anna Therese Kryczka DEDICATION To my family and friends with gratitude ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iv CIRRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 Historicism on the New Frontier: Making Taste in the Kennedy White House 23 CHAPTER 2 Oldenburg, Los Angeles, and A Certain America 65 CHAPTER 3 Art and Infrastructure: The Suburbs as Elsewhere 120 CHAPTER 4 Worthy Pleasure: TV, Video Art, and Cooking 168 CONCLUSION 229 BIBLIOGRAPHY 234 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to first thank my advisor Cécile Whiting whose prompt, thorough, and thoughtful guidance made the task of finishing the dissertation a joyful process. Her trust and support gave me the confidence to execute this project. My committee members Victoria Johnson and Catherine Liu were integral to the formation and articulation of this undertaking. Cécile, Vicky, and Catherine also importantly modeled three divergent and equally inspiring models of academic practice. I sincerely could not imagine a better committee. Beyond my committee, I wish to acknowledge Visual Studies faculty members Lucas Hilderbrand, Amy Powell, Bliss Lim, and Jamie Nisbet for their wise counsel and support. In anthropology I am grateful to have worked with and been encouraged by Keith Murphy, Bill Maurer, and Julia Elyachar. My dear friends and colleagues Robert J. Kett, Meredith Goldsmith, and Laura Holzman provided invaluable editorial and emotional support. -

Warren Commission, Volume XVII: CE

("'it Ient'8t FILE No. 1-16-602 .111 TREY DEPARTMENT 7 UNITED S'L'ATES SECRET SERVICE Washington, D. C . White House Detail November 30, 1963 FINi,L SURVEY RE7CRT Re : Visit of the President, Mrs . Kennedy, the Vice President, and Mrs . Johnson to Dallas, Texas, where they were scheduled to attend a luncheon and the President was to speak. This luncheon was sponsored by the Dallas Citizens Council, the Dallas Assembly, and the Science Research Center on November 22, 1963 . Mr . James J. Rowley Chief, U . S. Secret Service Washington, D. C. Sir: INTRODUCTION Reference is made to my preliminary survey report dated November 19, 1963. This survey was conducted by SA Winston Iawson, Office 1-16, and SAIC Forrest Sorrels, Office 3-3, and assisted by SA David Grant, Office 1-16, from November 13 through November 22, 1963. SA Jerry Kivett, Office i-22, coordinated the Vice President's plans for the visit from November 18 through November 22, 1963. A large crowd was on hand to greet the Presidential Party at the airport. The motorcade route was lined by crowds which were quite large, especially in the downtown area . The invited guests were awaiting the arrival of the Presidential Party at the Trade Dart, the site of the luncheon and speech . Appropriate attire for this luncheon was a business suit . ITINERARY 11:35 a.m. The Vice President and Mrs. Johnson accompanied by other members of the party arrived at Lave Field, Dallas, Texas, aboard AF #2. (See attached Proposed Manifest for AF #2 - Fort Worth to Dallas .) Attachment #1 Confidential . -

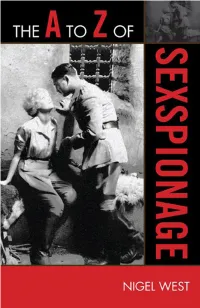

Nigel West, 2009

OTHER A TO Z GUIDES FROM THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. 1. The A to Z of Buddhism by Charles S. Prebish, 2001. 2. The A to Z of Catholicism by William J. Collinge, 2001. 3. The A to Z of Hinduism by Bruce M. Sullivan, 2001. 4. The A to Z of Islam by Ludwig W. Adamec, 2002. 5. The A to Z of Slavery & Abolition by Martin A. Klein, 2002. 6. Terrorism: Assassins to Zealots by Sean Kendall Anderson and Stephen Sloan, 2003. 7. The A to Z of the Korean War by Paul M. Edwards, 2005. 8. The A to Z of the Cold War by Joseph Smith and Simon Davis, 2005. 9. The A to Z of the Vietnam War by Edwin E. Moise, 2005. 10. The A to Z of Science Fiction Literature by Brian Stableford, 2005. 11. The A to Z of the Holocaust by Jack R. Fischel, 2005. 12. The A to Z of Washington, D.C. by Robert Benedetto, Jane Dono- van, and Kathleen DuVall, 2005. 13. The A to Z of Taoism by Julian F. Pas, 2006. 14. The A to Z of the Renaissance by Charles G. Nauert, 2006. 15. The A to Z of Shinto by Stuart D. B. Picken, 2006. 16. The A to Z of Byzantium by John H. Rosser, 2006. 17. The A to Z of the Civil War by Terry L. Jones, 2006. 18. The A to Z of the Friends (Quakers) by Margery Post Abbott, Mary Ellen Chijioke, Pink Dandelion, and John William Oliver Jr., 2006 19. -

Jacqueline Kennedy and the Refashioning of American Cultural Visuality in the Early 1960S

Wesleyan University The Honors College A Transformation of the First Ladyship: Jacqueline Kennedy and the Refashioning of American Cultural Visuality in the Early 1960s by Maria Nicole Massad Class of 2016 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in History Middletown, Connecticut April 12, 2016 Acknowledgements Before I begin my analysis of Jacqueline Kennedy’s First Ladyship, I want to thank several people without whom their guidance this project might never have been possible. First, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis advisor, Professor Patricia Hill. I owe so much to your wisdom, good judgment, and enthusiasm for my project. You helped me better articulate my ideas and strengthen my writing into a more cohesive argument. Your direction and support have been invaluable, and I sincerely thank you for your mentorship. To my academic advisor, Professor Ronald Schatz, who has cheered me on throughout my career as a student of history at Wesleyan University and ardently encouraged my decision to write a thesis. I am so grateful that I chose to take your “20th Century U.S. History” course; after all, it planted the seed of inquiry in my mind to investigate the impact of American culture during the 1960s. To Lauren Noyes and the staff of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, I thank you for assisting with my research endeavors in the archives this past summer. If not for your help, this project would not have come to fruition. -

One Day's Passage of Power from the Motorcade, to the Hospital, to Air Force One—And to the White House

. THE %V.IHT‘f.TON PfisT fit/VI 1)qr-3 Jack 'Mena One Day's Passage of Power From the motorcade, to the hospital, to Air Force One—and to the White House. rode serenely in the motorcade in the sixth Icar following the open convertible carrying President Kennedy and his wife, as well as John Connally, the governor of Texas, and his wife, Nellie. My advertising agency was han- dling the press during the Texas visit by the president and the vice president, and I came to that Dallas motorcade as the guest of Vice President Johnson. The day began so full of promise, the motor- cade moving slowing by teeming crowds along the streets, nary a hostile sign, only prolonged cheers and warm waves of affection from my fellow Texans. Liz Carpenter smiled happily at me, They do love this president, don't they?" she murmured. We turned under the overpass and around the grassy knoll onto Dealey Plaza nearing a building of forgettable architecture called the Texas School Book Depository: And then began those few minutes of wild disproportion, a ricochet of fear wrapped in ter- ror inside a nightmare. The car in front of us leaped forward, tires screaming against pave- ment, an Indianapolis racer. The sidewalks swarmed with people. The laughter vanished. 1t6"IN F [I The hospitable faces now puzzled, somber. FS Liz Carpenter, Pamela Turnure (Mrs. Ken- nedy's press secretary), Evelyn Lincoln (Pres- ident Kennedy's secretary) and I looked at each other in bewilderment. What was amiss? Sometimes the brain baffles the entry of a question it does not choose to answer, so hauntingly barren of virtue is the query. -

JACQUELINE KENNEDY and the POLITICS of POPULARITY by COURTNEY CAUDLE TRAVERS DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Th

JACQUELINE KENNEDY AND THE POLITICS OF POPULARITY BY COURTNEY CAUDLE TRAVERS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor John Murphy, Chair Associate Professor Cara Finnegan Associate Professor Ned O’Gorman Associate Professor Jennifer Greenhill Associate Professor Pat Gill Abstract Although her role as first lady marked the real beginning of the American public’s fascination with her, Jacqueline Kennedy’s celebrity status endured throughout her life. Dozens of books have sought to chronicle that mystique, hail her style, and commend her contribution to the youthful persona of the Kennedy administration. She seems to be an object ripe for rhetorical study; yet, for many communication scholars, Kennedy’s cultural iconicity diminishes her legacy as First Lady, and she remains an exemplar of political passivity. Her influence on the American public’s cultural and political imagination, however, demonstrates a need for scholars to assess with greater depth her development from First Lady to American icon in the early 1960s. Thus, this dissertation focuses on three case studies that analyze Jacqueline Kennedy’s image across different media: fashion spreads in Vogue magazine and Harper’s Bazaar published immediately after the inauguration in 1961; her televised tour of the White House broadcast in February 1962; and Andy Warhol’s 1964 Jackie prints, which drew from her construction of the Camelot myth after JFK’s funeral. These case studies seek to show how “icon” becomes an inventional and conceptual resource for the role of a modern first lady and how Kennedy’s shift to public icon in her own right (after and outside of her position as first lady) was mediated in nuanced ways that both reflected early Cold War (suburban) culture and shaped the larger institutional discourses of which she was part. -

RADIATION LEAK PROFESSOR RELATES .. Spy" I Ne I DENT

LOtI TiDE 11/20/63 1.1 AT 0038 :lite HOURGLASS 1.3 AT 1213 HOURGLASS WEDNESDAY 20 NOVEMBER 1963 :--------------------------------~----------------------------_T--------------------------------------------------------------1 ; DIRECTOR OF AMTED i VISITS KWAJALEIN r RADIATION PROFESSOR RELATES f I .. Spy" INe I DENT ! LEAK LO~DON (uPI )--THE ATOMIC WASHINGTON (UPI )--YALE PROFESSOR FREDERICK BARGHOORN ENERGY AUTHORITY DISCLOSED SAID TODAY HE WAS GRABBED BY POLICE AND HUSTLED TO JAIL TONIGHT SiX PERSONS RE JUST OUTSIDE THE ~ETROPOLE HOTEL IN Moscow IMMEDIATELY CEiVED A DOSE OF RADIATION AfTER A "YOUNGISH MAN WHO SPOKE ENGLISH" THRUST A ROLL OF WHEN RADIOACTIVE FUEL FROM PAPERS INTO HIS HANDS AN ADVANCED GAS-COOLED RE BARGHOORN, WHO ~ADE THE DiSCLOSURE AT A NEWS CONFERENCE AC~R WAS PUT INTO AN UN HELD AFTER A LENGTHY CONFERENCE WITH STATE DEPARTMENT SHIELDED HOLE AT THE WIND OFFICIALS, DECLINED TO DESCRiBE THE AFFAIR FLATLY AS A SC~lE ATOMIC ENERGY PLANT "FRAMEUP," BUT HE SAID REPORTERS HAD THE~CTS AND COULD A SPOKESMAN SAID THE IN DRAW THEIR CONCLUSIONS CiDENT TOOK Pl~CE SATURDAY BARGHOORN SAID HE WAS JUST PREPARING TO ENTER THE HOTEL WHERE HE WAS AWARDED THE AND THE REACTOR WAS CLOSED ABOUT 7 25 P.M OCTOBER 3' TO PREPARE FOR HIS PLANNED BACHELOR OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN DOWN. WORKERS WERE EVAC DEPARTURE EARLY THE NEXT MORNING fOR WARSAW CHEMISTRY IN 1934 HE UATED BECAUSE OF THE DANGER HE SAID THAT HE HAD JUST SAID GOODBYE TO A FRIEND AND I RECEIVED A COMMISSION AS "ALTHOUGH SIX PERSONS RE WAS TURNING TO GO INTO THE HOTEL wHEN A "YOUNGISH LOOKING ! 2ND LT. -

THE DEVIL HAS HIS OWN RULES King Solomon Consolidated His Power by Ordering Jesus Told Us That the Devil Is a Liar and a Murderer

I have been following the 2016 presidential election truth, because there is no truth in him. When and what I saw in the news at the beginning of March he speaketh a lie, he speaketh of his own: for made me angry. The Holy Spirit gave me a message he is a liar, and the father of it.” (John 8:44) th as I slept and then I during the night of March 20 If someone is blocking the Devil’s agenda, he will was directed away from the sermon the next day to resort to violence and murder. When God did not go speak on this subject. along with the Devil’s sacrificial program, he moved I am not endorsing any Republican candidate but I upon Cain and enticed him to murder his brother. do want to share what the Holy Spirit told me about (Genesis 4:3-12) this presidential race. I absolutely cannot support Deception, intrigue and murder are all trademarks of any Democratic candidate since they stand for Satan’s activities and this is evident over the course murdering babies, homosexual marriage, more taxes of history. and eroding the rights of Americans in the name of freedom and prosperity. King David had several sons; each one was vying to become the next king of Israel. Amnon and Absalom Donald Trump has been a member of the Republican came from different mothers and were not friendly party for some time and when he announced his toward each other. When Amnon raped his half- decision to run for the presidency, he registered with sister, it gave Absalom the excuse he needed to the Republican party and agreed to abide by the murder his half-brother. -

House of Representatives

1961 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - HOUSE 17889 long-range financing feature faces a tough will be- protected against expropriation or level, not by the Federal Government. But fight in the House and in the Senate which currency blocking; and what steps have youth crime is becoming so serious In many is now working on the a,id bill. been or will be taken to, remove aid officials areas that I have introduced a bill to help "The Senate opened debate on the aid bill 'whose performance is unsatisfactory.' local communities tack1e ·it. Attorney Gen last week. The House will take up the bill "Representative JOHN BRADEMAS, Demo eral Robert Kennedy and Secretaries Gold later. crat, of Indiana, spokesman for the group, berg of Labor and Ribicoff of Health, Educa "Senator KEATING said in a statement that said that although its members believe in tion, and Welfare have all testified in support long-range aid planning was of crucial im foreign aid, 'we are also convinced that our of the bill, which would: (1) finance pilot portance. aid program abroad can be conducted more projects to find better techniques to combat "BERLIN CRISIS CITED efficiently and effectively.'" delinquency, and make the findings available "Senator HUMPHREY declared in a separate The new Soviet feat of orbiting a man nationwide, (2) help train more specialists statement that the Berlin crisis had under around the world for 25 hours is more dra to deal with delinquents and youthful of lined the need for consistent long-term aid matic evidence that in the struggle with the fenders. -

Nancy Tuckerman & Pamela Turnure, Oral History Interview

Nancy Tuckerman & Pamela Turnure, Oral History Interview – 1964 Administrative Information Creator: Nancy Tuckerman and Pamela Turnure Interviewer: Mrs. Wayne Fredericks Date of Interview: 1964 Length: 50 pages Biographical Note Tuckerman was social secretary to Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy (1963). Turnure served as a receptionist and secretary in Senator John F. Kennedy’s (JFK) office and later as press secretary to Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy. In this interview they discuss state visits and state dinners at the White House, Patrick Bouvier Kennedy’s short life and death, and JFK’s assassination and funeral, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed January 28, 1965, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any materials from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law.