Rapid Assessment -Report-Nepal.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SECOND KATHMANDU VALLEY WATER SUPPLY IMPROVEMENT PROJECT Procurement Workshop Kathmandu, 10 February 2021 Kathmandu – Demography

SECOND KATHMANDU VALLEY WATER SUPPLY IMPROVEMENT PROJECT Procurement Workshop Kathmandu, 10 February 2021 Kathmandu – Demography • Population ~ 3 million; floating population ~1.2 million • Average household size – 4.2 persons • 575 sq.km Valley Area • 18 municipalities, 3 districts (Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, and Lalitpur) • Bell shaped valley with elevation varying from 1400m at periphery – 1280m • About 500 hotels; 44000 beds; Average 5000 tourists per day SKVWSIP – Institutional Arrangements Institution SKVWSIP Implementation Structure MWS Executing Agency Project Implementation Directorate – KUKL Implementing Agency – Distribution network (PID-KUKL) and House service connections Melamchi Water Supply Development Board Implementing Agency – Bulk water (MWSDB) infrastructure SKVWSIP – Project Area WTP & DNI COVERAGE AREA SUNDARIJAL WTP JORPATI N JORPATI S CHABAHIL GOTATHAR PEPSICOLA KIRTIPUR THIMMI BHAKTAPUR SKVWSIP – Overview & Timeline • Total estimated project cost – $230 million • Project area: Greenfield development outside Ring Road in Kathmandu Valley • Limited public water supply network; reliance on KUKL tankers, borewells, hand pumps, traditional water sources and private tankers • Beneficiaries: About 110,000 households Aspects Arrangements Commencement of procurement First half of 2021 Implementation period January 2022 – December 2028 Completion date December 2028 SKVWSIP – Procurement Packages Scope Indicative number of contracts WTP (255 MLD) 1 Distribution network (about 700 km total) 3–4 Structural retrofitting of Headwork structure of Melamchi water 1 diversion IT-based decision support system for O&M of Melamchi Tunnel 1 IT-based early warning system for Melamchi Headworks 1 Capacity building of KUKL to strengthen operational and technical 2 competencies Project Consultants 2 Proposed Distribution Network Packages under Second Kathmandu Valley Water Supply Improvement Project Procurement Workshopt Presentation to Prospective Bidders for New DNI packages (DNI-8, 9 & 10) PID-KUKL Feb 2021 Location of DNI Packages Outside Ring Road (DNI pkg. -

Kathmandu - Bhaktapur 0 0 0 0 5 5

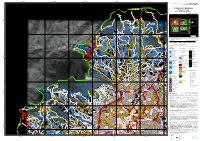

85°12'0"E 85°14'0"E 85°16'0"E 85°18'0"E 85°20'0"E 322500 325000 327500 330000 332500 335000 337500 GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSN012 Product N.: Reference - A1 NEPAL, v2 Kathmandu - Bhaktapur 0 0 0 0 5 5 7 7 Reference map 7 7 0 0 3 3 2014 - Detail 25k Sheet A1 Production Date: 18/07/2014 N " 0 ' n 8 4 N ° E " !Gonggabu 7 E ú A1 A2 A3 0 2 E E ' 8 E !Jorpati 4 ! B Jhormahankal ° ! n ú B !Kathmandu 7 ! B n 2 !Kirtipur n Madhy! apur Sangla ú !Bhaktapur ú ú ú n ú B1 B2 ú n ! B ! ú B 0 0 0 0 0 n Kabhresthali n 0 5 5 7 7 0 0 3 3 0 5 10 km /" n n ú ú ú n ú n n n Cartographic Information ! ! B B ! B ú ! B ! n B 1:25000 Full color A1, low resolution (100 dpi) ! WX B ! ú B n Meters n ú ú 0 n n 10000 n 20000 30000 40000 50000 XY ! B ú ú Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 45N map coordinate system ni t ! ú B a ! Jitpurphedi ú B Tick Marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system ú i n m d n u a ICn n n N n h ! B ! B Legend s ! B i ! B ! n B ! B ! B B ! B n n n ! n B n TokhaChandeswori Hydrography Transportation Urban Areas úú n ! B ! B ! Crossing Point (<500m) Built Up Area n RB iver Line (500>=nm) ! B ! ! B B ! B ú ! ! B B ú n ! ú B WXWX Intermittent Bridge Point Agricultural ! B ! B ! B ! ! ú B B Penrennial WX Culvert Commercial ! B ú ú n River Area (>=1Ha) XY n Ford Educational N n ! B " n n n n n Intermittent Crossing Line (>=500m) Industrial 0 ! B ' n ! ! B B 6 ! B IC ! B Perennial Bridge 4 0 n 0 Institutional N ° E 0 n 0 n E " 7 5 ú Futung ú n5 ! Reservoir Point (<1Ha) B 2 2 0 2 E Culvert ' Medical 7 E 7 6 0 n E 0 õö 3 ú 3 IC 4 Reservoir Point -

Tables Table 1.3.2 Typical Geological Sections

Tables Table 1.3.2 Typical Geological Sections - T 1 - Table 2.3.3 Actual ID No. List of Municipal Wards and VDC Sr. No. ID-No. District Name Sr. No. ID-No. District Name Sr. No. ID-No. District Name 1 11011 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.1 73 10191 Kathmandu Gagalphedi 145 20131 Lalitpur Harisiddhi 2 11021 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.2 74 10201 Kathmandu Gokarneshwar 146 20141 Lalitpur Imadol 3 11031 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.3 75 10211 Kathmandu Goldhunga 147 20151 Lalitpur Jharuwarasi 4 11041 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.4 76 10221 Kathmandu Gongabu 148 20161 Lalitpur Khokana 5 11051 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.5 77 10231 Kathmandu Gothatar 149 20171 Lalitpur Lamatar 6 11061 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.6 78 10241 Kathmandu Ichankhu Narayan 150 20181 Lalitpur Lele 7 11071 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.7 79 10251 Kathmandu Indrayani 151 20191 Lalitpur Lubhu 8 11081 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.8 80 10261 Kathmandu Jhor Mahakal 152 20201 Lalitpur Nallu 9 11091 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.9 81 10271 Kathmandu Jitpurphedi 153 20211 Lalitpur Sainbu 10 11101 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.10 82 10281 Kathmandu Jorpati 154 20221 Lalitpur Siddhipur 11 11111 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.11 83 10291 Kathmandu Kabresthali 155 20231 Lalitpur Sunakothi 12 11121 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.12 84 10301 Kathmandu Kapan 156 20241 Lalitpur Thaiba 13 11131 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.13 85 10311 Kathmandu Khadka Bhadrakali 157 20251 Lalitpur Thecho 14 11141 Kathmandu Kathmandu Ward No.14 86 10321 Kathmandu Lapsephedi 158 20261 Lalitpur Tikathali 15 11151 Kathmandu -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register Summary 81 78 4 12-2017 325A1 026069 3 0 0 0 3 5100 59 59 4 10-2017 325A1

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF JANUARY 2018 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 5100 026069 BIRATNAGAR NEPAL 325A1 4 12-2017 78 3 0 0 0 3 81 5100 026071 KATHMANDU NEPAL 325A1 4 10-2017 59 2 0 0 -2 0 59 5100 045033 DANTAKALI DHARAN NEPAL 325A1 4 10-2017 28 4 0 0 0 4 32 5100 045852 KATHMANDU KANTIPUR NEPAL 325A1 4 01-2018 20 7 0 0 0 7 27 5100 047934 ITAHARI SUNSARI NEPAL 325A1 4 01-2018 53 3 0 0 0 3 56 5100 051652 DOLAKHA NEPAL 325A1 4 08-2017 32 0 0 0 0 0 32 5100 055540 DHARAN VIJAYAPUR NEPAL 325A1 4 01-2018 35 5 0 0 0 5 40 5100 057925 KATHMANDU JORPATI NEPAL 325A1 4 01-2018 86 3 0 0 -5 -2 84 5100 058165 BIRATNAGAR CENTRAL NEPAL 325A1 4 01-2018 50 3 0 0 0 3 53 5100 058239 BHADRAPUR NEPAL 325A1 4 03-2017 15 0 0 0 0 0 15 5100 058317 BIRTAMOD NEPAL 325A1 4 09-2017 30 2 0 0 0 2 32 5100 059404 KATHMANDU KANCHANJUNGA NEPAL 325A1 4 08-2011 9 0 0 0 0 0 9 5100 060064 KATHMANDU GOKARNESHWOR NEPAL 325A1 4 01-2018 35 4 0 0 -3 1 36 5100 060085 DINGLA BHOJPUR NEPAL 325A1 4 10-2017 72 0 0 0 -16 -16 56 5100 060130 KATHMANDU PASHUPATI NATH NEPAL 325A1 4 01-2018 40 8 0 0 -1 7 47 5100 060280 URLABARI NEPAL 325A1 4 10-2017 30 5 0 0 -1 4 34 5100 060294 KATHMANDU UNITED NEPAL 325A1 4 01-2018 81 8 0 0 -9 -1 80 5100 060628 KATHMANDU UNIVERSAL NEPAL 325A1 4 01-2018 45 6 1 0 0 7 52 5100 061068 KATHMANDU MAHANKAL NEPAL 325A1 4 12-2017 22 3 0 0 0 3 25 5100 061553 KATHMANDU SUKUNDA -

2000 Microbial Contamination in the Kathmandu Valley Drinking

MICROBIAL CONTAMINATION IN THE KATHMANDU VALLEY DRINKING WATER SUPPLY AND BAGMATI RIVER Andrea N.C. Wolfe B.S. Engineering, Swarthmore College, 1999 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ENGINEERING IN CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE, 2000 © 2000 Andrea N.C. Wolfe. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 5, 2000 Certified by: Susan Murcott Lecturer and Research Engineer of Civil and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Daniele Veneziano Chair, Departmental Committee on Graduate Studies MICROBIAL CONTAMINATION IN THE KATHMANDU VALLEY DRINKING WATER SUPPLY AND BAGMATI RIVER by Andrea N.C. Wolfe SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING ON MAY 5, 2000 IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ENGINEERING IN CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING ABSTRACT The purpose of this investigation was to determine and describe the microbial drinking water quality problems in the Kathmandu Valley. Microbial testing for total coliform, E.coli, and H2S producing bacteria was performed in January 2000 on drinking water sources, treatment plants, distribution points, and consumption points. Existing studies of the water quality problems in Kathmandu were also analyzed and comparisons of both data sets characterized seasonal, treatment plant, and city sector variations in the drinking water quality. Results showed that 50% of well sources were microbially contaminated and surface water sources were contaminated in 100% of samples. -

Kathmandu - Bhaktapur 0 0 0 0 5 5

85°22'0"E 85°24'0"E 85°26'0"E 85°28'0"E 85°30'0"E 340000 342500 345000 347500 350000 352500 GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSN012 Product N.: Reference - A2 NEPAL, v2 Kathmandu - Bhaktapur 0 0 0 0 5 5 7 7 Reference map 7 7 0 0 3 3 2014 - Detail 25k Sheet A2 Production Date: 18/07/2014 N " A1 !Gonggabu A2 A3 0 ' 8 !Jorpati 4 E N ° E " ! 7 Kathmandu E 0 ' 2 E E 8 4 ! ° Kirtipur Madh!yapur ! 7 Bhaktapur 2 B1 B2 0 ú 0 0 Budanilkantha 0 ! B 0 0 5 5 7 7 0 di n 0 3 Na Sundarijal 3 0 5 10 km /" ati um ! hn B Bis ! B ! B ú Cartographic Information 1:25000 Full color A1, high resolution (300 dpi) ! B ! B n ChapaliBhadrakali Meters ú nn n 0 10000 20000 30000 40000 50000 n n Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 45N map coordinate system ! B ! B Tick Marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system n n ú ú n n WX Legend n n n n ! B Hydrography Transportation Urban Areas n ! B ! River Line (500>=m) Crossing Point (<500m) B d n Built Up Area a ú o ú R Intermittent Bridge Point Agricultural ! n in B ! B ! ! ú B a B ú n Perennial WX M ! Culvert Commercial r ú n B ú ta õö u River Area (>=1Ha) XY lf Ford Educational o n ! G n B n n Intermittent Crossing Line (>=500m) Industrial n ú Perennial Bridge 0 0 Institutional N n 0 n 0 " n ú 5 5 0 Reservoir Point (<1Ha) 2 2 Culvert ' Medical 7 7 6 ú 0 0 õö 4 3 3 E N Reservoir Point ° Ford E " Military 7 E 0 ' 2 E Reservoir Area (>=1Ha) 4 ú n Baluwa E 6 Ï Tunnel Point (<500m) Other 4 ! B IC ° ! B Intermittent ! B n n n 7 TunnelLine (>=500m) ú n 2 Recreational/Sports n Perennial n n Airfield Point (<1Ha) Religious ú n Ditch -

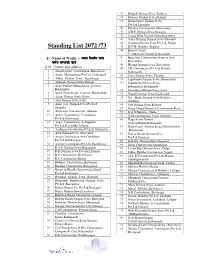

Standing List 2072 /73 45 H.S.W

37 Deepak Nirman Sewa, Rajbiraj 38 Dharma Nirman Sewa,Kritipur 39 Dronacharya Nirman Sewa Pvt.Ltd,Lazimpat 40 Eklabya Construction, Manamaiju 41 G.R.P. Nirman Sewa,Nuwakot 42 Ganga Mata Nirman Sewa,Baneshwor 43 Glory Tamang Nirman Sewa,Nuwakot 44 Gokarna Nirman Sewa Pvt.Ltd, Jorpati Standing List 2072 /73 45 H.S.W. Builders ,Dapcha 46 Hamro Unnati Costruction,Chabahil,Kathmandu 1) Name of Works :- ejg lgdf{0f tyf 47 Him Jyoti Construction Services,New dd{t ;DaGwL sfo{ Baneshwor 48 Hosana Nirman Sewa ,Koteshwor S.N Name and address 49 I.K. Construction Pvt.Ltd, Kalanki 1 Aarati Lawati Construction ,Baneshwor Kathmandu 2 Aasan Multipurpose Pvt.Ltd, Chakrapath 50 Ishan Nirman Sewa, Thankot 3 Abh ay Nirman Sewa , Jagritinagar 51 Jagadamba Nirman Sewa ,Babarmahal 4 Abhinab Nirman Sewa,Suntaal 52 Jagadamba Nirman Sewa, 5 Acme Facility Management Services , Babarmahal,Kathmandu Bakhundole 53 Janaadarsa Nirman Sewa, kavre 6 Acme Technotrade Concern Bakhundole 54 Jhapali Nirman Sewa,Putalisadak 7 Agrim Nirman Sewa ,Kavre 55 Jiri - Shikri Nirman Sewa Pvt.Ltd , 8 Ajay Nirman Sewa,Teku Gothatar 9 Amar jyoti Nirman Sewa Pvt.Ltd., 56 Juju Nirman Sewa,Kritipur Sitapaila 57 Jyang Chup Chhyothul Construction,Kavre 10 Amikshya Construction ,Gothatar 58 K & S Builders , Dallu 11 Aneva Engineering Consultancy 59 K.M Construction, Sewa, Nuwakot Pvt.Ltd,Anamnagar 60 Kageshowri Nirman 12 Angat Construction & Suppliers Sewa,Gothatar,Kathmandu Pvt.Ltd,Harisiddhi Lalitpur 61 Kalinchowk Nirman Sewa,Gokarneshwor 13 Aradhana Construction Pvt.Ltd, Khumaltar ,Kathmandu 14 Arun Nirman Sewa Ghattekulo 62 Kausil Basnet Nirman Sewa 15 Aryan Construction And Consultant Pvt.Ltd,Bijeshori Pvt.Ltd,Buddhanagar 63 Kausitar Nirman Sewa,Nagarkot 16 Asmita Construction Pvt.Ltd ,Baneshwor 64 Kiran Construction,Anamnagar 17 B.A.S Nirman Sewa Manamaiju 65 Laxmi Puja Nirman Sewa , Dolpa 18 B.B. -

Rural Electrification, Distribution, and Transmission Project

RESETTLEMENT PLAN THANKOT-CHAPAGAON-BHAKTAPUR 132 kV TRANSMISSION LINE PROJECT for the RURAL ELECTRIFICATION, DISTRIBUTION AND TRANSMISSION PROJECT in NEPAL Nepal Electricity Authority This report was prepared by the Borrower and is not an ADB document. May 2004 NEPAL ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY (AN UNDERTAKING OF HIS MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL) TRANSMISSION AND SYSTEM OPERATIONS TRANSMISSION LINE/SUBSTATION CONSTRUCTION DEPARTMENT THANKOT-CHAPAGAON-BHAKTAPUR 132 Kv TRANSMISSION LINE PROJECT RURAL ELECTRIFICATION, DISTRIBUTION AND TRANSMISSION PROJECT (ADB LOAN NO. 1732-NEP: (SF) & OPEC LOAN NO. 825 P) INDEPENDENT ASSESSMENT OF ACQUISITION, COMPENSATION, REHABILITATION PLAN (ACRP) FINAL REPORT Prepared by: Dr. Toran Sharma Mr. Hari P. Bhattarai (Independent Consultants) May 2004 Foreword The independent consultants as per the request of ADB to NEA prepare this Resettlement Plan (RP). This RP is based on the data already collected by NEA and its consultants at different times and the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and ACRP with short Resettlement Plan Reports of the Transmission Line Project, approved by the concerned ministries of HMG and reviewed by ADB. The independent consultants have reviewed all the available reports in the context of ADB Guideline for Resettlement. In the process of independent assessment, the consultants made revisit of the T/L alignment and relocate house structures. Similarly, plant/vegetation and crop inventories have been prepared to assess the losses. Extensive discussion were held with the NEA officials for the development of the resettlement policy framework for the project, taking consideration of the HMG’s rules, regulations and practices and ADB policy on resettlement. The report presented is in the ADB report format and addresses the issues as per the ADB requirement. -

NEPAL: Kathmandu - Operational Presence Map (As of 30 Jun 2015)

NEPAL: Kathmandu - Operational Presence Map (as of 30 Jun 2015) As of 30 June 2015, 110 organizations are reported to be working in Kathmandu district Number of organizations per cluster Health Shelter NUMBER OF ORGANI WASH Protection Protection Education Nutrition 22 5 1 20 20 40 ZATIONS PER VDC No. of Org Gorkha Health No data Dhading Rasuwa 1 Nuwakot 2 - 4 Makawanpur Shelter 5 - 7 8 - 18 Sindhupalchok INDIA CHINA Kabhrepalanchok No. of Org Dolakha Sindhuli Ramechhap Education No data 1 No. of Org Okhaldunga 2 - 10 WASH 11- 15 No data 16 - 40 1 - 2 Creation date: Glide number: Sources: 3 - 4 The boundaries and names shown and the desi 4 - 5 No. of Org 10 July 20156 EQ-2015-000048-NPL- 8 Cluster reporting No data No. of Org 1 2 Nutrition gnations used on this map do not imply offici 3 No data 4 1 2 - 5 6 - 10 11 - 13 al endorsement or acceptance by the Uni No. of Org Feedback: No data [email protected] www.humanitarianresponse.info1 2 ted Nations. 3 4 Kathmandu District List of organizations by VDC and cluster Health Protection Shelter and NFI WASH Nutrition Edaucation VDC name Alapot UNICEF,WHO Caritas Nepal,HDRVG SDPC Restless Badbhanjyang UNICEF,WHO HDRVG OXFAM SDPC Restless Sangkhu Bajrayogini HERD,UNICEF,WHO IRW,MC IMC,OXFAM SDPC NSET Balambu UNICEF,WHO GIZ,LWF IMC UNICEF,WHO DCWB,Women for Human Rights Caritas Nepal RMSO,Child NGO Foundation Baluwa Bhadrabas UNICEF,WHO SDPC Bhimdhunga UNICEF,WHO WV NRCS,WV SDPC Restless JANTRA,UNICEF,WHO,CIVCT Nepal DCWB,CIVCT Nepal,CWISH,The Child NGO Foundation,GIZ,Global SDPC Restless Himalayan Innovative Society Medic,NRCS,RMSO Budhanilkantha UNICEF,WHO ADRA,AWO International e. -

Culture and Entrepreneurship in the Tibetonepalese

CARPETS, MARKETS AND MAKERS CARPETS, MARKETS AND MAKERS: CULTURE AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN THE TIBETO-NEPALESE CARPET INDUSTRY BY TOM O'NEILL B.F.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School ofGraduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment ofthe Requirements for the degree Doctor ofPhilosophy McMaster University ©Copyright by Tom O'Neill, September, 1997 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (1997) McMaster University (Anthropology) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Carpets, Markets and Makers: Culture and Entrepreneurship in the Tibeto Nepalese Carpet Industry. AUTHOR: Thomas O'Neill, B.F.A.(York University), M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor William R. Rodman NUMBER OF PAGES: viii, 249 11 ABSTRACT This dissertation is an ethnography of local entrepreneurship in the Tibeto Nepalese carpet industry in Kathmandu, Ward 6 (Boudha) and the Jorpati Village Development Committee, Nepal. This industry achieved dramatic growth during the last decade, after European carpet buyers developed with Tibetan refugee exporters a hybrid 'Tibetan' carpet that combined European design with Tibetan weaving technique. As a result, thousands ofTibetan and Nepalese entrepreneurs came to occupy a new economic niche that was a creation ofglobal commercial forces. This study is an analysis ofsurvey and ethnographic-data from among three hundred carpet manufactories. My primary research consultants were the entrepreneurs (saahu-ji) who operated at a time when the industry was subject to international criticism about the abuse ofchild labour. Many earlier reports claimed that up to one halfofall carpet labourers were children, but I found that by 1995 they were employed only infrequently, as a market downturn placed a premium on skilled weavers. The 'off season', as this market reduction is locally known, and the problem ofchild labour provides a temporal frame for this analysis. -

Government of Nepal

Government of Nepal District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) District Development Committee, KATHMANDU VOLUME-I (MAIN REPORT) AUGUST 2013 Submitted by SITARA Consult Pvt. Ltd. for the District Development Committee (DDC) and District Technical Office (DTO), Kathmandu with Technical Assistance from the Department of Local Infrastructure and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and grant supported by DFID. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This DTMP Final Report for Kathmandu District has been prepared on the basis of DOLIDAR’s DTMP Guidelines for the Preparation of District Transport Master Plan 2012. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to RTI Sector Maintenance Pilot and DOLIDAR for providing us an opportunity to prepare this DTMP. We would also like to acknowledge the valuable suggestions, guidance and support provided by DDC officials, DTO Engineers and DTICC members and all the participants present in various workshops organized during the preparation this DTMP without which this report would not be in the present form. At last but not the least, we would also like to express our sincere thanks to all the concerned who directly or indirectly helped us in preparing this DTMP. SITARA Consult Pvt. Ltd Kupondole, Lalitpur, Nepal i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Kathmandu District is located in Bagmati Zone of the Central Development Region of Nepal. It borders with Bhaktapur and Kavrepalanchowk district to the East, Dhading and Nuwakot district to the West, Nuwakot and Sindhupalchowk district to the north, Lalitpur and Makwanpur district to the South. The district has one metropolitan city, one municipality and fifty-seven VDCs, ten constituency areas. -

National Shelter Data Report the National Shelter Cluster Nepal Report Comes out Every Monday

Updated on July 3, 2015 National Shelter Data Report The National Shelter Cluster Nepal report comes out every Monday. Individual priority district reports will also come out at this time that identify where implementing agencies are active by VDC and current data listed by each VDC. This report will continually include more information. Email [email protected] if you have questions or suggestions on information you’d like to see in this report. Total Activities Completed Number of Active Agencies and Planned 697,008 Tarpaulin (single) Implementing agencies 132,264 CGI Bundle (72 feet/bundle) 83 Blankets (single) 318,820 Local Partner Agencies 19,042 Tents (single) 176 (Names not fully cleaned—some duplicates exist) 267,678 Household Kits (single) 50 Sourcing Agencies 397,140,335 Cash (NPR) (Names not fully cleaned—some duplicates exist) 6,597 Training (trained households) Completed Distribution 2011 Damage Household Tarpaulin CGI Bundle Blankets Tents Household Kits Cash Trainings Priority Districts (gov #'s) Census (one piece) (72ft / bundle) (one piece) (one piece) (one piece) (NPR) (not people) Bhaktapur 27,990 68,636 14,128 77 4,270 746 3,476 셁 4,497,500 Kathmandu 87,726 436,344 23,488 241 7,234 758 15,513 셁 8,327,694 Lalitpur 25,508 109,797 21,964 1,916 6,828 602 11,165 셁 7,470,136 Central Nuwakot 62,143 59,215 39,271 1,180 31,285 581 12,035 셁 8,407,500 Rasuwa 9,450 9,778 11,496 3,255 9,907 94 12,844 셁 - Dolakha 52,000 45,688 76,696 4,302 55,720 54 15,377 셁 7,787,500 Kabhrepalanchok 73,647 80,720 35,103 1,339 6,770 625