Inflammation and Activated Innate Immunity in the Pathogenesis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Influence of Infection and Inflammation on Biomarkers of Nutritional Status

A2.4 INFLUENCE OF INFECTION AND INFLAMMATION ON BIOMARKERS OF NUTRITIONAL STATUS A2.4 Influence of infection and inflammation on biomarkers of nutritional status with an emphasis on vitamin A and iron David I. Thurnham1 and George P. McCabe2 1 Northern Ireland Centre for Food and Health, University of Ulster, Coleraine, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland 2 Statistics Department, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, United States of America Corresponding author: David I. Thurnham; [email protected] Suggested citation: Thurnham DI, McCabe GP. Influence of infection and inflammation on biomarkers of nutritional status with an emphasis on vitamin A and iron. In: World Health Organization. Report: Priorities in the assessment of vitamin A and iron status in populations, Panama City, Panama, 15–17 September 2010. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2012. Abstract n Many plasma nutrients are influenced by infection or tissue damage. These effects may be passive and the result of changes in blood volume and capillary permeability. They may also be the direct effect of metabolic alterations that depress or increase the concentration of a nutrient or metabolite in the plasma. Where the nutrient or metabolite is a nutritional biomarker as in the case of plasma retinol, a depression in retinol concentrations will result in an overestimate of vitamin A deficiency. In contrast, where the biomarker is increased due to infection as in the case of plasma ferritin concentrations, inflammation will result in an underestimate of iron deficiency. Infection and tissue damage can be recognized by their clinical effects on the body but, unfortunately, subclinical infection or inflammation can only be recognized by measur- ing inflammation biomarkers in the blood. -

The Gut Microbiota and Inflammation

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review The Gut Microbiota and Inflammation: An Overview 1, 2 1, 1, , Zahraa Al Bander *, Marloes Dekker Nitert , Aya Mousa y and Negar Naderpoor * y 1 Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne 3168, Australia; [email protected] 2 School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane 4072, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (Z.A.B.); [email protected] (N.N.); Tel.: +61-38-572-2896 (N.N.) These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 10 September 2020; Accepted: 15 October 2020; Published: 19 October 2020 Abstract: The gut microbiota encompasses a diverse community of bacteria that carry out various functions influencing the overall health of the host. These comprise nutrient metabolism, immune system regulation and natural defence against infection. The presence of certain bacteria is associated with inflammatory molecules that may bring about inflammation in various body tissues. Inflammation underlies many chronic multisystem conditions including obesity, atherosclerosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammation may be triggered by structural components of the bacteria which can result in a cascade of inflammatory pathways involving interleukins and other cytokines. Similarly, by-products of metabolic processes in bacteria, including some short-chain fatty acids, can play a role in inhibiting inflammatory processes. In this review, we aimed to provide an overview of the relationship between the gut microbiota and inflammatory molecules and to highlight relevant knowledge gaps in this field. -

Innate Immunity and Inflammation

ISBTc ‐ Primer on Tumor Immunology and Biological Therapy of Cancer InnateInnate ImmunityImmunity andand InflammationInflammation WillemWillem Overwijk,Overwijk, Ph.D.Ph.D. MDMD AndersonAnderson CancerCancer CenterCenter CenterCenter forfor CancerCancer ImmunologyImmunology ResearchResearch Houston,Houston, TXTX www.allthingsbeautiful.com InnateInnate ImmunityImmunity andand InflammationInflammation • Definitions • Cells and Molecules • Innate Immunity and Inflammation in Cancer • Bad Inflammation • Good Inflammation • Therapeutic Implications InnateInnate ImmunityImmunity andand InflammationInflammation • Definitions • Cells and Molecules • Innate Immunity and Inflammation in Cancer • Bad Inflammation • Good Inflammation • Therapeutic Implications • Innate Immunity: Immunity that is naturally present and is not due to prior sensitization to an antigen; generally nonspecific. It is in contrast to acquired/adaptive immunity. Adapted from Merriam‐Webster Medical Dictionary • Innate Immunity: Immunity that is naturally present and is not due to prior sensitization to an antigen; generally nonspecific. It is in contrast to acquired/adaptive immunity. • Inflammation: a local response to tissue injury – Rubor (redness) – Calor (heat) – Dolor (pain) – Tumor (swelling) Adapted from Merriam‐Webster Medical Dictionary ““InnateInnate ImmunityImmunity”” andand ““InflammationInflammation”” areare vaguevague termsterms •• SpecificSpecific cellcell typestypes andand moleculesmolecules orchestrateorchestrate specificspecific typestypes ofof inflammationinflammation -

Effect of Exercise Intensity on Cell-Mediated Immunity

sports Perspective Effect of Exercise Intensity on Cell-Mediated Immunity Katsuhiko Suzuki 1,* and Harumi Hayashida 2 1 Faculty of Sport Sciences, Waseda University, 2-579-15 Mikajima, Tokorozawa 359-1192, Japan 2 Faculty of Culture and Sport Policy, Toin University of Yokohama, 1614 Kurogane-cho, Aoba-ku, Yokohama 225-8503, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-4-2947-6898 Abstract: Moderate-intensity exercise is considered to enhance immune function and to be useful for preventing acute upper respiratory infections and similar conditions. Many people practice low- intensity short-duration exercise with the expectation of a beneficial effect on immunocompetency. However, it is difficult to affirm the existence of definite evidence of such a benefit. In this article, we discuss the effects of low-intensity short-duration exercise on cell-mediated immunity, and contrast them to the effects of high-intensity and long-duration exercise. Whereas high-intensity exercise induces inflammation and reduces cell-mediated immune system function, low-intensity exercise does not appear to have a large effect on either inflammation or cell-mediated immune function. Low-intensity exercises such as walking and yoga, which are helpful to relieve stress, cannot be considered as harmful to the immune system. Although yoga was shown to impose fewer restrictions on breathing and physical strain, the evidence that yoga enhances cell-mediated immunity remains insufficient. Therefore, further studies are needed to examine the exercise mode that may be most effective for improvement of immune functions. Keywords: exercise; walking; yoga; cellular immune system; cytokines; inflammation 1. -

An EANM Procedural Guideline

European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-018-4052-x GUIDELINES Clinical indications, image acquisition and data interpretation for white blood cells and anti-granulocyte monoclonal antibody scintigraphy: an EANM procedural guideline A. Signore1 & F. Jamar2 & O. Israel3 & J. Buscombe4 & J. Martin-Comin5 & E. Lazzeri6 Received: 27 April 2018 /Accepted: 6 May 2018 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract Introduction Radiolabelled autologous white blood cells (WBC) scintigraphy is being standardized all over the world to ensure high quality, specificity and reproducibility. Similarly, in many European countries radiolabelled anti-granulocyte antibodies (anti-G-mAb) are used instead of WBC with high diagnostic accuracy. The EANM Inflammation & Infection Committee is deeply involved in this process of standardization as a primary goal of the group. Aim The main aim of this guideline is to support and promote good clinical practice despite the complex environment of a national health care system with its ethical, economic and legal aspects that must also be taken into consideration. Method After the standardization of the WBC labelling procedure (already published), a group of experts from the EANM Infection & Inflammation Committee developed and validated these guidelines based on published evidences. Results Here we describe image acquisition protocols, image display procedures and image analyses as well as image interpre- tation criteria for the use of radiolabelled WBC and monoclonal antigranulocyte antibodies. Clinical application for WBC and anti-G-mAb scintigraphy is also described. Conclusions These guidelines should be applied by all nuclear medicine centers in favor of a highly reproducible standardized practice. Keywords Infection . -

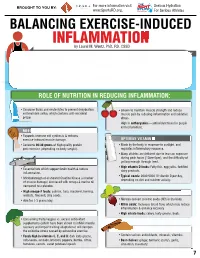

INFLAMMATION MICRONUTRIENTS SOURCES FUNCTION by Laurel M

For more information visit Serious Hydration For more information visit Serious Hydration BROUGHT TO YOU BY: BROUGHT TO YOU BY: For more information visit Serious Hydration www.SportsRD.org. For Serious Athletes www.SportsRD.org. For Serious Athletes www.SportsRD.org. NASA DEVELOPED For Serious Athletes NUTRITIONAL SUPPORT FOR INJURY BALANCING EXERCISE-INDUCED RECOVERY AND RETURN-TO-PLAY INFLAMMATION MICRONUTRIENTS SOURCES FUNCTION by Laurel M. Wentz, PhD, RD, CSSD Vitamin C Citrus fruit, red and green peppers, Antioxidant, wound healing, tissue repair, EXERCISE-INDUCED INFLAMMATION IS THE BODY’S RESPONSE TO INJURY DUE TO INTENSE PHYSICAL ACTIVITY cantaloupe immune function • The immune system response causes redness, swelling, pain. Vitamin A Sweet potato, spinach, carrots, Cell growth and development, • Acute inflammation is a normal response to high-intensity exercise, but prolonged (chronic) tomatoes immune function inflammation is a sustained response that affects the entire body. Vitamin D Sun exposure, oily fish, Promotes calcium absorption and bone health • Prolonged Inflammation: dairy products, fortified foods 1. Causes fatigue, muscle damage and soreness. 2. Limits muscle growth and training progression and increases muscle loss. Calcium Low-fat milk, fortified non-dairy milk, Supports skeletal structure and function 3. Modulating prolonged inflammation may enhance recovery & reduce soreness. low-fat Greek yogurt, cheese, broccoli, kale, fortified orange juice Magnesium Almonds, sesame and sunflower Nucleic acid and protein -

A Role of Inflammation and Immunity in Essential Hypertension—Modeled and Analyzed Using Petri Nets

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article A Role of Inflammation and Immunity in Essential Hypertension—Modeled and Analyzed Using Petri Nets Dorota Formanowicz 1 , Agnieszka Rybarczyk 2,3 , Marcin Radom 2,3 and Piotr Formanowicz 2,3,* 1 Department of Clinical Biochemistry and Laboratory Medicine, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, 60-806 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] 2 Institute of Computing Science, Poznan University of Technology, 60-965 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] (A.R.); [email protected] (M.R.) 3 Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry, Polish Academy of Sciences, 61-704 Poznan, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 April 2020; Accepted: 5 May 2020; Published: 9 May 2020 Abstract: Recent studies have shown that the innate and adaptive immune system, together with low-grade inflammation, may play an important role in essential hypertension. In this work, to verify the importance of selected factors for the development of essential hypertension, we created a Petri net-based model and analyzed it. The analysis was based mainly on t-invariants, knockouts of selected fragments of the net and its simulations. The blockade of the renin-angiotensin (RAA) system revealed that the most significant effect on the emergence of essential hypertension has RAA activation. This blockade affects: (1) the formation of angiotensin II, (2) inflammatory process (by influencing C-reactive protein (CRP)), (3) the initiation of blood coagulation, (4) bradykinin generation via the kallikrein-kinin system, (5) activation of lymphocytes in hypertension, (6) the participation of TNF alpha in the activation of the acute phase response, and (7) activation of NADPH oxidase—a key enzyme of oxidative stress. -

Products & Technology Wound Inflammation and the Role of A

Products & technology Wound inflammation and the role of a multifunctional polymeric dressing Temporary inflammation is a normal response in acute wound healing. However, in chronic wounds, the inflammatory phase is dysfunctional in nature. This results in delayed healing, and causes further problems such as increased pain, odour and Intro high levels of exudate production. It is important to choose a dressing that addresses all of these factors while meeting the patient’s needs. Multifunctional polymeric Authors: Keith F Cutting membrane dressings (e.g. PolyMem®, Ferris) can help to simplify this choice and Authors: Peter Vowden assist healthcare professionals in chronic wound care. The unique actions of xxxxx Cornelia Wiegand PolyMem® have been proven to reduce and prevent inflammation, swelling, bruising and pain to promote rapid healing, working in the deep tissues beneath the skin[1,2]. he mechanism of acute wound healing — the vascular and cellular stages. During is a well-described complex cellular vascular response, immediately on injury there is T interaction[3] that can be divided into an initial transient vasoconstriction that can be several integrated processes: haemostasis, measured in seconds. This is promptly followed inflammation, proliferation, epithelialisation by vasodilation under the influence of histamine and tissue remodeling. Inflammation is a key and nitric oxide (NO) that cause an inflow of blood. component of acute wound healing, clearing An increase in vascular permeability promotes damaged extracellular matrix, cells and debris leakage of serous fluid (protein-rich exudate) into from zones of tissue damage. This is normally a the extravascular compartment, which in turn time-limited orchestrated process. Successful increases the concentration of cells and clotting progression of the inflammatory phase allows factors. -

Impact and Associations of Eosinophilic Inflammation in COPD: Analysis of the AERIS Cohort

ORIGINAL ARTICLE COPD Impact and associations of eosinophilic inflammation in COPD: analysis of the AERIS cohort Viktoriya L. Kim1,2,3, Ngaire A. Coombs4, Karl J. Staples 1,2,5, Kristoffer K. Ostridge 1,2, Nicholas P. Williams1,2, Stephen A. Wootton3, Jeanne-Marie Devaster6, Emmanuel Aris6, Stuart C. Clarke2,5, Andrew C. Tuck7, Simon C. Bourne2,8 and Tom M.A. Wilkinson1,2,5 on behalf of the AERIS Study Group9 Affiliations: 1NIHR Southampton Respiratory Biomedical Research Unit, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, Southampton, UK. 2Clinical and Experimental Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. 3NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, Southampton, UK. 4Primary Care and Population Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. 5Wessex Investigational Sciences Hub, University of Southampton Faculty of Medicine, Southampton General Hospital, Southampton, UK. 6GSK Vaccines, Rixensart, Belgium. 7Faculty of Medicine and Institute for Life Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. 8Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust, Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth, UK. 9Members of the AERIS Study Group are listed in the Acknowledgements section. Correspondence: Tom M.A. Wilkinson, Mailpoint 810, Level F, South Block, Southampton General Hospital, Southampton, SO16 6YD, UK. E-mail: [email protected] @ERSpublications Blood eosinophil levels in COPD predict the nature of inflammation at future exacerbations and may guide therapy http://ow.ly/W10o30dNQiq Cite this article as: Kim VL, Coombs NA, Staples KJ, et al. Impact and associations of eosinophilic inflammation in COPD: analysis of the AERIS cohort. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1700853 [https://doi.org/ 10.1183/13993003.00853-2017]. -

Cd47-Sirpα Interaction and IL-10 Constrain Inflammation-Induced Macrophage Phagocytosis of Healthy Self-Cells

Cd47-Sirpα interaction and IL-10 constrain inflammation-induced macrophage phagocytosis of healthy self-cells Zhen Biana,b, Lei Shia, Ya-Lan Guoa, Zhiyuan Lva, Cong Tanga, Shuo Niua, Alexandra Tremblaya, Mahathi Venkataramania, Courtney Culpeppera, Limin Lib, Zhen Zhoub, Ahmed Mansoura, Yongliang Zhangc, Andrew Gewirtzd, Koby Kiddera,e, Ke Zenb, and Yuan Liua,d,1 aProgram of Immunology and Cell Biology, Department of Biology, Center for Diagnostics & Therapeutics, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 30302; bState Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Nanjing Advanced Institute for Life Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu 210093, China; cDepartment of Microbiology and Immunology, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, Life Science Institute (LSI) Immunology Programme, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117456; dCenter for Inflammation, Immunity and Infection, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 30303; and eDepartment of Cell Biology, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 Edited by Jason G. Cyster, University of California, San Francisco, CA, and approved July 11, 2016 (received for review October 28, 2015) − − Rapid clearance of adoptively transferred Cd47-null (Cd47 / ) cells in The CD47-SIRPα mechanism was first reported by Oldenborg congeneic WT mice suggests a critical self-recognition mechanism, et al. (1), who had demonstrated in red blood cell (RBC) in which CD47 is the ubiquitous marker of self, and its interaction transfusion experiments that WT mice rapidly eliminate syngeneic − with macrophage signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) triggers inhib- Cd47-null (Cd47 ) RBCs through erythrophagocytosis in the itory signaling through SIRPα cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine- spleen and that the lack of tyrosine phosphorylation in SIRPα based inhibition motifs and tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1/2. -

Inflamm-Aging of Hematopoiesis, Hematopoietic Stem Cells, and the Bone Marrow Microenvironment

REVIEW published: 14 November 2016 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00502 inflamm-Aging of Hematopoiesis, Hematopoietic Stem Cells, and the Bone Marrow Microenvironment Larisa V. Kovtonyuk1†, Kristin Fritsch1†, Xiaomin Feng2, Markus G. Manz1 and Hitoshi Takizawa2* 1 Division of Hematology, University Hospital Zurich, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 2 International Research Center for Medical Sciences, Kumamoto, Japan All hematopoietic and immune cells are continuously generated by hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) through highly organized process of stepwise lineage commitment. In the steady state, HSCs are mostly quiescent, while HPCs are actively proliferating and contributing to daily hematopoiesis. In response to hematopoietic challenges, e.g., life-threatening blood loss, infection, and inflammation, HSCs can be activated to proliferate and engage in blood formation. The HSC activation Edited by: induced by hematopoietic demand is mediated by direct or indirect sensing mechanisms Laura Schuettpelz, Washington University involving pattern recognition receptors or cytokine/chemokine receptors. In contrast in St. Louis, USA to the hematopoietic challenges with obvious clinical symptoms, how the aging pro- Reviewed by: cess, which involves low-grade chronic inflammation, impacts hematopoiesis remains Katherine C. MacNamara, Albany Medical College, USA undefined. Herein, we summarize recent findings pertaining to functional alternations Dan Link, of hematopoiesis, HSCs, and the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment during the pro- Washington University cesses of aging and inflammation and highlight some common cellular and molecular in St. Louis, USA changes during the processes that influence hematopoiesis and its cells of origin, HSCs *Correspondence: Hitoshi Takizawa and HPCs, as well as the BM microenvironment. We also discuss how age-depen- [email protected] dent alterations of the immune system lead to subclinical inflammatory states and how †Larisa V. -

Inflammasomes and the Maintenance of Hematopoietic Homeostasis

molecules Review Inflammasomes and the Maintenance of Hematopoietic Homeostasis: New Perspectives and Opportunities Lijing Yang, Mengjia Hu, Yukai Lu, Songling Han and Junping Wang * State Key Laboratory of Trauma, Burns and Combined Injury, Institute of Combined Injury, Chongqing Engineering Research Center for Nanomedicine, College of Preventive Medicine, Third Military Medical University, Chongqing 400038, China; [email protected] (L.Y.); [email protected] (M.H.); [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (S.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-023-68771515 Abstract: Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) regularly produce various blood cells throughout life via their self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation abilities. Most HSCs remain quiescent in the bone marrow (BM) and respond in a timely manner to either physiological or pathological cues, but the underlying mechanisms remain to be further elucidated. In the past few years, accumulating evidence has highlighted an intermediate role of inflammasome activation in hematopoietic maintenance, post-hematopoietic transplantation complications, and senescence. As a cytosolic protein complex, the inflammasome participates in immune responses by generating a caspase cascade and inducing cytokine secretion. This process is generally triggered by signals from purinergic receptors that integrate extracellular stimuli such as the metabolic factor ATP via P2 receptors. Furthermore, targeted modulation/inhibition of specific inflammasomes may help to maintain/restore adequate hematopoietic homeostasis. In this review, we will first summarize the possible relationships between inflammasome activation and homeostasis based on certain interesting phenomena. The cellular Citation: Yang, L.; Hu, M.; Lu, Y.; and molecular mechanism by which purinergic receptors integrate extracellular cues to activate Han, S.; Wang, J.