Long-Term Immunological Health Consequences of COVID-19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

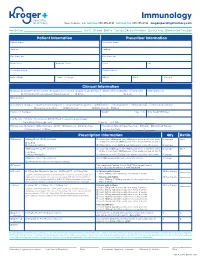

Immunology New Orleans, LA Toll Free 888.355.4191 Toll Free Fax 888.355.4192 Krogerspecialtypharmacy.Com

Immunology New Orleans, LA toll free 888.355.4191 toll free fax 888.355.4192 krogerspecialtypharmacy.com Need By Date: _________________________________________________ Ship To: Patient Office Fax Copy: Rx Card Front/Back Clinical Notes Medical Card Front/Back Patient Information Prescriber Information Patient Name Prescriber Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Main Phone Alternate Phone Phone Fax Social Security # Contact Person Date of Birth Male Female DEA # NPI # License # Clinical Information Diagnosis: J45.40 Moderate Asthma J45.50 Severe Asthma L20.9 Atopic Dermatitis L50.1 Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria (CIU) Eosinophil Levels J33 Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis Other: ________________________________ Dx Code: ___________ Drug Allergies Concomitant Therapies: Short-acting Beta Agonist Long-acting Beta Agonist Antihistamines Decongestants Immunotherapy Inhaled Corticosteroid Leukotriene Modifiers Oral Steroids Nasal Steroids Other: _____________________________________________________________ Please List Therapies Weight kg lbs Date Weight Obtained Lab Results: History of positive skin OR RAST test to a perennial aeroallergen Pretreatment Serum lgE Level: ______________________________________ IU per mL Test Date: _________ / ________ / ________ MD Specialty: Allergist Dermatologist ENT Pediatrician Primary Care Prescription Type: Naïve/New Start Restart Continued Therapy Pulmonologist Other: _________________________________________ Last Injection Date: _________ / ________ -

Influence of Infection and Inflammation on Biomarkers of Nutritional Status

A2.4 INFLUENCE OF INFECTION AND INFLAMMATION ON BIOMARKERS OF NUTRITIONAL STATUS A2.4 Influence of infection and inflammation on biomarkers of nutritional status with an emphasis on vitamin A and iron David I. Thurnham1 and George P. McCabe2 1 Northern Ireland Centre for Food and Health, University of Ulster, Coleraine, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland 2 Statistics Department, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, United States of America Corresponding author: David I. Thurnham; [email protected] Suggested citation: Thurnham DI, McCabe GP. Influence of infection and inflammation on biomarkers of nutritional status with an emphasis on vitamin A and iron. In: World Health Organization. Report: Priorities in the assessment of vitamin A and iron status in populations, Panama City, Panama, 15–17 September 2010. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2012. Abstract n Many plasma nutrients are influenced by infection or tissue damage. These effects may be passive and the result of changes in blood volume and capillary permeability. They may also be the direct effect of metabolic alterations that depress or increase the concentration of a nutrient or metabolite in the plasma. Where the nutrient or metabolite is a nutritional biomarker as in the case of plasma retinol, a depression in retinol concentrations will result in an overestimate of vitamin A deficiency. In contrast, where the biomarker is increased due to infection as in the case of plasma ferritin concentrations, inflammation will result in an underestimate of iron deficiency. Infection and tissue damage can be recognized by their clinical effects on the body but, unfortunately, subclinical infection or inflammation can only be recognized by measur- ing inflammation biomarkers in the blood. -

IFM Innate Immunity Infographic

UNDERSTANDING INNATE IMMUNITY INTRODUCTION The immune system is comprised of two arms that work together to protect the body – the innate and adaptive immune systems. INNATE ADAPTIVE γδ T Cell Dendritic B Cell Cell Macrophage Antibodies Natural Killer Lymphocites Neutrophil T Cell CD4+ CD8+ T Cell T Cell TIME 6 hours 12 hours 1 week INNATE IMMUNITY ADAPTIVE IMMUNITY Innate immunity is the body’s first The adaptive, or acquired, immune line of immunological response system is activated when the innate and reacts quickly to anything that immune system is not able to fully should not be present. address a threat, but responses are slow, taking up to a week to fully respond. Pathogen evades the innate Dendritic immune system T Cell Cell Through antigen Pathogen presentation, the dendritic cell informs T cells of the pathogen, which informs Macrophage B cells B Cell B cells create antibodies against the pathogen Macrophages engulf and destroy Antibodies label invading pathogens pathogens for destruction Scientists estimate innate immunity comprises approximately: The adaptive immune system develops of the immune memory of pathogen exposures, so that 80% system B and T cells can respond quickly to eliminate repeat invaders. IMMUNE SYSTEM AND DISEASE If the immune system consistently under-responds or over-responds, serious diseases can result. CANCER INFLAMMATION Innate system is TOO ACTIVE Innate system NOT ACTIVE ENOUGH Cancers grow and spread when tumor Certain diseases trigger the innate cells evade detection by the immune immune system to unnecessarily system. The innate immune system is respond and cause excessive inflammation. responsible for detecting cancer cells and This type of chronic inflammation is signaling to the adaptive immune system associated with autoimmune and for the destruction of the cancer cells. -

The Gut Microbiota and Inflammation

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review The Gut Microbiota and Inflammation: An Overview 1, 2 1, 1, , Zahraa Al Bander *, Marloes Dekker Nitert , Aya Mousa y and Negar Naderpoor * y 1 Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne 3168, Australia; [email protected] 2 School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane 4072, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (Z.A.B.); [email protected] (N.N.); Tel.: +61-38-572-2896 (N.N.) These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 10 September 2020; Accepted: 15 October 2020; Published: 19 October 2020 Abstract: The gut microbiota encompasses a diverse community of bacteria that carry out various functions influencing the overall health of the host. These comprise nutrient metabolism, immune system regulation and natural defence against infection. The presence of certain bacteria is associated with inflammatory molecules that may bring about inflammation in various body tissues. Inflammation underlies many chronic multisystem conditions including obesity, atherosclerosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammation may be triggered by structural components of the bacteria which can result in a cascade of inflammatory pathways involving interleukins and other cytokines. Similarly, by-products of metabolic processes in bacteria, including some short-chain fatty acids, can play a role in inhibiting inflammatory processes. In this review, we aimed to provide an overview of the relationship between the gut microbiota and inflammatory molecules and to highlight relevant knowledge gaps in this field. -

White Blood Cells and Severe COVID-19: a Mendelian Randomization Study

Journal of Personalized Medicine Article White Blood Cells and Severe COVID-19: A Mendelian Randomization Study Yitang Sun 1 , Jingqi Zhou 1,2 and Kaixiong Ye 1,3,* 1 Department of Genetics, Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA; [email protected] (Y.S.); [email protected] (J.Z.) 2 School of Public Health, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200025, China 3 Institute of Bioinformatics, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-706-542-5898; Fax: +1-706-542-3910 Abstract: Increasing evidence shows that white blood cells are associated with the risk of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), but the direction and causality of this association are not clear. To evaluate the causal associations between various white blood cell traits and the COVID-19 susceptibility and severity, we conducted two-sample bidirectional Mendelian Randomization (MR) analyses with summary statistics from the largest and most recent genome-wide association studies. Our MR results indicated causal protective effects of higher basophil count, basophil percentage of white blood cells, and myeloid white blood cell count on severe COVID-19, with odds ratios (OR) per standard deviation increment of 0.75 (95% CI: 0.60–0.95), 0.70 (95% CI: 0.54–0.92), and 0.85 (95% CI: 0.73–0.98), respectively. Neither COVID-19 severity nor susceptibility was associated with white blood cell traits in our reverse MR results. Genetically predicted high basophil count, basophil percentage of white blood cells, and myeloid white blood cell count are associated with a lower risk of developing severe COVID-19. -

WHITE BLOOD CELLS Formation Function ~ TEST YOURSELF

Chapter 9 Blood, Lymph, and Immunity 231 WHITE BLOOD CELLS All white blood cells develop in the bone marrow except Any nucleated cell normally found in blood is a white blood for some lymphocytes (they start out in bone marrow but cell. White blood cells are also known as WBCs or leukocytes. develop elsewhere). At the beginning of leukopoiesis all the When white blood cells accumulate in one place, they grossly immature white blood cells look alike even though they're appear white or cream-colored. For example, pus is an accu- already committed to a specific cell line. It's not until the mulation of white blood cells. Mature white blood cells are cells start developing some of their unique characteristics larger than mature red blood cells. that we can tell them apart. There are five types of white blood cells. They are neu- Function trophils, eosinophils, basophils, monocytes and lymphocytes (Table 9-2). The function of all white blood cells is to provide a defense White blood cells can be classified in three different ways: for the body against foreign invaders. Each type of white 1. Type of defense function blood cell has its own unique role in this defense. If all the • Phagocytosis: neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, mono- white blood cells are functioning properly, an animal has a cytes good chance of remaining healthy. Individual white blood • Antibody production and cellular immunity: lympho- cell functions will be discussed with each cell type (see cytes Table 9-2). 2. Shape of nucleus In providing defense against foreign invaders, the white • Polymorphonuclear (multilobed, segmented nucleus): blood cells do their jobs primarily out in the tissues. -

We Work at the Intersection of Immunology and Developmental Biology

Development and Homeostasis of Mucosal Tissues U934/UMR3215 – Genetics and Developmental Biology Pedro Hernández Chef d'équipe [email protected] We work at the intersection of immunology and developmental biology. Our primary goal is to understand how immune responses impact the development, integrity and function of mucosal tissue layers, such as the intestinal epithelium, during homeostasis and upon different types of stress, including infections. To study these questions we exploit the advantages of the zebrafish model such as ex utero and rapid development, transparency, large progeny, and simple genetic manipulation. We combine live imaging, flow cytometry, single-cell transcriptomics, and models inducing mucosal stress, including pathogenic challenges. Our research can be subdivided into three main topics: 1) Protection of intestinal epithelial integrity since early development: Epithelial cells are at the core of intestinal organ function. They are in charge of absorbing nutrients and water, and at the same time constitute a barrier for potential pathogens and harmful molecules. Epithelial cells perform all these functions before full development of the immune system, which promotes epithelial barrier function upon injury. We study how robust epithelial integrity is achieved prior and after maturation of the intestinal immune system, with a focus on the function of mucosal cytokines. 2) Epithelial-leukocyte crosstalk throughout development: Intestines become vastly populated by leukocytes after exposure to external cues from diet and colonization by the microbiota. We have recently reported the existence and diversity of zebrafish innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), a key component of the mucosal immune system recently discovered in mice and humans. ILCs mediate immune responses by secreting cytokines such as IL-22 which safeguards gut epithelial integrity. -

Adaptive Tdetect Fact Sheet for Recipient

FACT SHEET FOR RECIPIENTS Coronavirus Adaptive Biotechnologies Corporation September 2, 2021 Disease 2019 T-Detect COVID Test (COVID-19) You are being given this Fact Sheet because your coughing, difficulty breathing, etc.). A full list of sample is being tested or was tested for an adaptive T- symptoms of COVID-19 can be found at the following cell immune response to the virus that causes link: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) using the T- ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Detect COVID Test. How are people tested for COVID-19? Two main kinds of tests are currently available for You should not interpret the results of this COVID-19: diagnostic tests and adaptive immune response tests. test to indicate the presence or absence of immunity or protection from COVID-19 • A diagnostic test tells you if you have a current infection. infection. • An adaptive immune response test tells you if you may have had a previous infection This Fact Sheet contains information to help you understand the risks and benefits of using this test to What is the T-Detect COVID Test? evaluate your adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV- This test is similar to an antibody test in that it measures 2, the virus that causes COVID-19. After reading this your adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV-2, the Fact Sheet, if you have questions or would like to virus that causes COVID-19. However in this case it discuss the information provided, please talk to your specifically measures your adaptive T-cell immune healthcare provider. -

Role of the Microbiology Laboratory in Infection Control

GUIDE TO INFECTION CONTROL IN THE HOSPITAL CHAPTER 3: Role of the Microbiology Laboratory in Infection Control Author Mohamed Benbachir, PhD Chapter Editor Gonzalo Bearman MD, MPH, FACP, FSHEA, FIDSA Topic Outline Key Issues Known Facts Suggested Practice Suggested Practice in Under-Resourced Settings Summary References Chapter last updated: January, 2018 KEY ISSUES The microbiology laboratory plays an important role in the surveillance, treatment, control and prevention oF nosocomial inFections. The microbiologist is a permanent and active member oF the infection control committee (ICC) and the antimicrobial stewardship group (ASG). Since most of the inFection control and antimicrobial stewardship programs rely on microbiological results, quality assurance is an important issue. KNOWN FACTS The microbiologist is a daily privileged interlocutor oF the infection control team (inFection control doctor and inFection control nurse) and the antimicrobial stewardship working group. The First task oF the microbiology laboratory is to accurately, consistently and rapidly identiFy the responsible agents to species level and identify their antimicrobial resistance patterns. Traditional microbiologic methods remain suboptimal in providing rapid identification and susceptibility testing. There is a growing need for more rapid and reliable laboratory results. Important progress made in the fields of instruments, reagents and techniques have made it easier to adapt to the important changes oF the clinical microbiology context e.g. increasing use of microbiology tests, shortage of qualiFied personnel. There is also a growing demand For quality in clinical laboratories and more and more countries are elaborating national regulations. 1 The microbiology processes are becoming increasingly more complex. InFormatics are playing an increasing role in the improvement oF these processes in terms oF workFlow, timeliness and cost. -

Our Immune System (Children's Book)

OurOur ImmuneImmune SystemSystem A story for children with primary immunodeficiency diseases Written by IMMUNE DEFICIENCY Sara LeBien FOUNDATION A note from the author The purpose of this book is to help young children who are immune deficient to better understand their immune system. What is a “B-cell,” a “T-cell,” an “immunoglobulin” or “IgG”? They hear doctors use these words, but what do they mean? With cheerful illustrations, Our Immune System explains how a normal immune system works and what treatments may be necessary when the system is deficient. In this second edition, a description of a new treatment has been included. I hope this book will enable these children and their families to explore together the immune system, and that it will help alleviate any confusion or fears they may have. Sara LeBien This book contains general medical information which cannot be applied safely to any individual case. Medical knowledge and practice can change rapidly. Therefore, this book should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice. SECOND EDITION COPYRIGHT 1990, 2007 IMMUNE DEFICIENCY FOUNDATION Copyright 2007 by Immune Deficiency Foundation, USA. Readers may redistribute this article to other individuals for non-commercial use, provided that the text, html codes, and this notice remain intact and unaltered in any way. Our Immune System may not be resold, reprinted or redistributed for compensation of any kind without prior written permission from Immune Deficiency Foundation. If you have any questions about permission, please contact: Immune Deficiency Foundation, 40 West Chesapeake Avenue, Suite 308, Towson, MD 21204, USA; or by telephone at 1-800-296-4433. -

Immunology Stories: How Storytelling Can Help Us to Make Sense of Complex Topics

Immunology Stories: How Storytelling Can Help Us to Make Sense of Complex Topics Jennifer Giuliani, MSc Camosun College, Lansdowne Campus, 3100 Foul Bay Rd, Victoria BC V8P 5J2 [email protected] Abstract The immune response is a wonderfully complex aspect of our physiology that can sometimes confound students and instructors alike. How do we wade through the layers of detail to help our students develop an understanding of immunology? In this article, I will share some of the stories about immunology research that helped me strengthen my own understanding and improve my approach to helping students learn and understand this topic. In addition, we will explore some of the research on the power of storytelling, and how learning through stories might be a defining characteristic of what it means to be human. https://doi.org/10.21692/haps.2020.105 Key words: storytelling, immunology Introduction I have been trying to understand the immune response for a My personal journey to develop a better understanding of long time. Like many Anatomy and Physiology instructors, I the immune system was a compelling reminder to me of the did not have an immunology background beyond what was power of storytelling. Suddenly I saw examples of storytelling covered in my undergraduate physiology courses. When the everywhere that I saw authentic learning. In this article, I will time came for me to teach students about the immune system, share some of what I have learned about learning through I relied heavily on the information presented in our textbooks. stories, some of the fun and fascinating immunology stories I was able to present students with the key pieces of from Davis’ books, and my current approach to helping information and help them to remember a few facts, and the students understand the immune response. -

Year 11 GCSE History Paper 1 – Medicine Information Booklet

Paper 1 Medicine Key topics 1 and 2 (1250-1500, 1500-1700) Year 11 GCSE History Paper 1 – Medicine Information booklet Medieval Renaissance 1250-1500 1500-1750 Enlightenment Modern 1900-present 1700-1900 Case study: WW1 1 Paper 1 Medicine Key topics 1 and 2 (1250-1500, 1500-1700) Key topic 1.1 – Causes of disease 1250-1500 At this time there were four main ideas to explain why someone might become ill. Religious reasons - The Church was very powerful at this time. People would attend church 2/3 times a week and nuns and monks would care for people if they became ill. The Church told people that the Devil could infect people with disease and the only way to get better was to pray to God. The Church also told people that God could give you a disease to test your faith in him or sometimes send a great plague to punish people for their sins. People had so much belief in the Church no-one questioned the power of the Church and many people had believed this explanation of illness for over 1,000 years. Astrology -After so many people in Britain died during the Black Death (1348-49) people began to look for new ways to explain why they became sick. At this time doctors were called physicians. They would check someone’s urine and judge if you were ill based on its colour. They also believed they could work out why disease you had by looking at where the planets were when you were born.