An African Liberationist Reading of the Portrait of Paul in Acts 27

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 2 2/3/08 Acts 27 Paul the Apostle Had Appealed to Caesar, After Two

1 2 2/3/08 the record we have, they are J. Smith, The Voyage and Shipwreck of St. Paul and Sir William Acts 27 Ramsey, St. Paul, The Traveler and Roman citizen. Paul the apostle had appealed to Caesar, after two 27:1-8 The departure of Paul to Rome. years of being a political ploy of Felix and Festus, so Paul was going to be sent to Rome to stand 27:1 The boarding of the ship to Rome. before Caesar Nero. 1) The plural "we" last appeared six chapters before. vs. 1a God had told Paul that he was going to go to Rome * Acts 21:18 and bear witness of Him but the timing and the 2) Their port of arrival was to be Italy and way he was going to get there, was without doubt the word sail “apopleo” is a nautical not the way he had though it would take place. term, which appears six times in the remainder of the Acts. vs. 1a If we are committed to study the works of God, * Acts 27:4, 12, 21; 28:10-11 then the ways of God will never offend us, because 2) The apostle Paul was entrusted to a we know that He is just and righteous, therefore I centurion name Julius, along with other can not judge the ways of God by my prisoner. vs. 1b circumstances or emotions, only by His word! a) The Centurion Julius was in charge of 100 men Chapter 27-28:16 records for us the voyage to b) Those prisoners could of been for the Rome and the various details and could be gladiator shows or other cases to be compared to God’s promises to us, of one day presented before Caesar. -

In the Midst of the Storm” Acts 27:1–44 Previous Message Summary: Paul, Still B

b. How many people were aboard the ship and how many made it ashore? See Acts 27:37, 44. Small Group Questions 4. In Acts 27:3, the ship travels up the coast to Sidon “The Church Afire:”In the Midst of the Storm” where Julius frees Paul to go to his friends to provide Acts 27:1–44 for his needs. Previous Message Summary: Paul, still being held a. From verses 1-3 and 43, what do you know about captive by Governor Festus, had the opportunity to speak Julius? before King Agrippa and Bernice. Governor Festus was trying to come up with some reasonable charges against b. Why do you think a Roman soldier responsible for Paul. Paul gave us a great example of the different parts his prisoner’s captivity would let Paul go freely to of a testimony. his friends? We learned that: c. If you were the centurion, would you let your a. God is in the “story changing” business. prisoner have so much freedom? b. We need to carefully think through how to tell our story. c. We need to pray that God uses our story to help spread d. Can you share a time when you trusted someone His story. with a big responsibility? Did it pay off or were you disappointed? As you begin, you may want to read this passage in its entirety. 5. Paul warned the crew that the ship was headed for disaster if the voyage continued. Julius chose to listen Introduction to the ship’s pilot and owner. -

The Conversion of Paul Acts 8:26-40

Acts 2:1-15 - The coming of the Holy Spirit Acts 3:1-10 - Peter heals a crippled beggar Acts 4:1-21 - The apostles are imprisoned Acts was written by a chap called Luke, yes the same guy who wrote Luke’s Gospel. In fact, Acts is kind of like a part 2, picking up the story where the Gospel ends. Acts 8:26-40 - Philip preaches to the Ethiopian We think Luke was a doctor – Paul calls him doctor in his letter to the Colossians and the way Luke describes some of the healings and other Acts 9:1-19 - The conversion of Paul events makes us think he was an educated man and most likely a doctor. Acts 9:19-25 - Paul in Damascus Our best guess is that it was written between AD63 and AD70 – that’s Acts 9:32-43 - Aeneas healed & Dorcas brought back to life more than 1,948 years ago. It was written not long after the events described in the book and about 30 years after Jesus died and was raised Acts 10:19-48 - Peter and Cornelius to life again. Acts 12:4-11 - Peter arrested and freed by an angel Luke himself tells us at the beginning of his Gospel that he wanted to write about everything that had happened – he was actually with Paul Acts 13:1-3 - Paul and Barnabas sent off on a few of his journeys. He says that the book is for Theophilus (easy for you to say!), we think he was a wealthy man, possibly a Roman Acts 14:8-18 - Paul heals the crippled man in Lystra official. -

The Persecution of Christians in the First Century

JETS 61.3 (2018): 525–47 THE PERSECUTION OF CHRISTIANS IN THE FIRST CENTURY ECKHARD J. SCHNABEL* Abstract: The Book of Acts, Paul’s letters, 1 Peter, Hebrews, and Revelation attest to nu- merous incidents of persecution, which are attested for most provinces of the Roman empire, triggered by a wide variety of causes and connected with a wide variety of charges against the fol- lowers of Jesus. This essay surveys the twenty-seven specific incidents of and general references to persecution of Christians in the NT, with a focus on geographical, chronological, and legal matters. Key words: persecution, mission, hostility, opposition, Jerusalem, Rome, Peter, Paul, Acts, Hebrews, Revelation This essay seeks to survey the evidence in the NT for instances of the perse- cution of Jesus’ earliest followers in their historical and chronological contexts without attempting to provide a comprehensive analysis of each incident. The Greek term diōgmos that several NT authors use, usually translated as “persecu- tion,”1 is defined as “a program or process designed to harass and oppress some- one.”2 The term “persecution” is used here to describe the aggressive harassment and deliberate ill-treatment of the followers of Jesus, ranging from verbal abuse, denunciation before local magistrates, initiating court proceedings to beatings, flog- ging, banishment from a city, execution, and lynch killings. I. PERSECUTION IN JUDEA, SYRIA, AND NABATEA (AD 30–38/40) 1. Persecution in Jerusalem, Judea (I). Priests in Jerusalem, the captain of the tem- ple, and Sadducees arrested the apostles Peter and John who spoke to a crowd of * Eckhard J. -

ACTS 27 : Experiencing the Holy Spirit’S Peace in the Storm

ACTS 27 : Experiencing the Holy Spirit’s Peace in the Storm At times you see the storm coming and sometimes you do not. In this chapter of Acts we find Paul serene in the midst of not only a brutal storm but a disastrous shipwreck, as he rises from a prisoner on board to the acting, de-facto captain of the ship when others look to him for leadership. God enables His ambassadors1 to rise to any occasion, confident and filled with His peace2-- a fruit of the Holy Spirit which God knows His beloved need in turbulent times. “People should be able to see by the way we behave and think that God is real.”3 Let’s climb aboard and enter into this next stormy adventure with Paul, where he perseveres in sharing the faith in spite of the most dire of circumstances. Luke, a physician and most assuredly not a seasoned sailor, records each detail to chronicle Paul’s reaction and challenge each of us to stay afloat by means of our steadfast faith as well. In Acts 19:21, Paul confidently declared: “I must also see Rome.” Little did he know that he would travel 2,000 miles as a prisoner and survive surging ocean waves several stories high, a harrowing shipwreck, and poisonous snakes. Through it all, he held tightly to God’s promise in Acts 23:11, where the “Lord stood by him and said: __________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________.” 27:2 What portrait of friendship is found in Paul’s relationship with Luke and Aristarchus in Colossians 4:10, 14 and Philemon 23-24? ____________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ Life Application: Ponder Aristarchus, who “undertook a dangerous journey at the worst time of the year for sea voyages, simply to serve Paul—an example of friendship made stronger and deeper by faith in Christ. -

Paul Sails for Rome Acts 27 Characters: Narrator, Paul, Julius

1 Paul Sails for Rome Acts 27 Characters: Narrator, Paul, Julius, Ship Captain, Angel, Roman soldier Narrator: Paul and Silas have been thrown in jail a few times for preaching the Gospel. God provided Paul and Silas with a way out on both occasions. Once again though, Paul had been arrested for preaching about Jesus’ saving grace. Instead of stand trial in Jerusalem, Paul chose to have his trial in Rome, in front of the Roman Emperor Nero, which was his right to do because he was a Roman citizen. God had told Paul to go to Rome, to preach the Gospel, and Paul followed through. Paul and Silas were sailing to Rome on a Roman ship, which carried cargo, prisoners, and travelers. On the way, the ship encountered a very severe winter storm. Paul: Julius, we must dock at once. This storm will become very severe, and I can see this voyage killing many and destroying the cargo if we continue it. Narrator: Julius was the centurion in charge of bringing Paul to Rome for his trial. Because he wasn’t sure if Paul was telling the truth, he asked the ship’s captain. Julius: Captain, what do you think of this storm? Can we sail through it? Ship Captain: We must continue sailing—we are not able to stay the winter at Crete if we turn around, because our ship is too big. We will have to continue on, and dock at Phoenix. Narrator: The Centurion followed the captain’s advice, and allowed him to continue sailing the ship to Rome, instead of turning around. -

SHIPWRECK and PROVIDENCE the Mission Programme of Acts 27-28

SHIPWRECK AND PROVIDENCE The Mission Programme of Acts 27-28 Inauguraldissertation Zur Erlangung der Wurde eines Doktors Der Katholisch- Theologischen Fakultät Der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Vorgelegt von P. Dominic Mendonca O.P. München 2004 Thesis directed by: Prof. Hans-Joseph Klauck The second reader and the examiner: Prof. Haefner Date of the Oral Examination: 26th January 2004 Preface "All flesh shall see the salvation of God". These words of Isaiah which Luke puts on the lips of John the Baptist at the beginning of his Ministry provide a key to understanding Luke-Acts. The salvation which Jesus has brought in to the world must go beyond the confines of Jewish nation and reach the Gentiles as well. In the voyage narrative, the Gentiles benefit from the salvation without being converted to Christianity. The voyage narrative highlights the kind and hospitable behavior between Paul and the Gentiles. Such relationship is important for the rescue of all from the death by shipwreck, and in a symbolic way, for the salvation of all humanity. Living with the people of other Faiths in India has inspired me to study this issue of universal salvation in Acts 27-28. I am deeply grateful to Prof. Hans-Josef Klauck who encouraged me to explore this possibility. It is because of his guidance and timely suggestions that I have been able to complete my work. My gratitude extends to my Dominican Brothers of both Indian and South-German Province. I wish and pray that the message of kindness which Luke brings out so emphatically in the voyage narrative may reach all humanity. -

26-045 Sandt Luke Divine Sovereignty Acts

Tilburg University Divine guidance in Acts van de Sandt, H.W.M. Published in: Testamentum Imperium. An International Theological Journal Publication date: 2009 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): van de Sandt, H. W. M. (2009). Divine guidance in Acts: Dream-visions as pointers to the gentiles. Testamentum Imperium. An International Theological Journal, 2, 1-15. http://www.preciousheart.net/ti/2009/26- 045_Sandt_Luke_Divine_Sovereignty_Acts.pdf General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. sep. 2021 Testamentum Imperium – Volume 2 – 2009 www.PreciousHeart.net/ti Volume 2 – 2009 Divine Sovereignty in Acts: Divine Guidance in Acts: Dream–Visions as Pointers to the Gentiles Dr. H. W. M. van de Sandt1 Assistant Professor, Humanities University of Tilburg, the Netherlands2 Introduction A. -

Apostolic History of the Early Church

Scholars Crossing History of Global Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 Apostolic History of the Early Church Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_hist Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "Apostolic History of the Early Church" (2009). History of Global Missions. 1. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_hist/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of Global Missions by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. History and Survey of Missions ICST 355 Dr. Don Fanning There is no more dramatic history than how the Church, against all odds, could exist, much less expand worldwide, over the past 2000 years. This study seeks to honor and discover the significant contributions of the men and women, not unlike ourselves, yet in different circumstances, who made an impact in their generation. It can be said of them like David, who “served his own generation by the will of God…” (Acts 13:36). Apostolic History AD 33- 100 Page | 2 1 Apostolic History of the Early Church A.D. 33-100 Every science and philosophy attempts to learn from the past. Much of the study of the past becomes difficult, primarily because no living witness was there. Often the tendency is to read into the past our present circumstances in order to make them relevant. A classic illustration of this is Leonardo da Vinci’s 1498 painting of the Last Supper, in which the twelve Apostles and Jesus are seated on chairs behind a table served with plates and silverware. -

Rome at Last! Acts 27:1-‐28:16 Main Idea: God Keeps His Promises, So

Rome at Last! Acts 27:1-28:16 Main Idea: God keeps His promises, so we should trust Him and give thanks to Him. I. Tracing the Narrative (27:1-28:16) A. All Aboard (27:1-5) B. All Change (27:6-12) C. All Over (27:13-20) D. All Listen (27:21-26) E. All Stay (27:27-32) F. All Eat (27:33-38) G. All Survive (27:39-44) H. All Warm (28:1-10) I. All Arrive (28:11-16) II. Thanking God and Taking Courage Many people book cruises on the Mediterranean Sea; and for good reason. It’s beautiful. The cities along the coast are fascinating and historically significant. Cruises are also relaxing and luxurious. The ships are vacations in themselves. In Acts 27, Paul sails on the Mediterranean, but his trip is nothing like a refreshing cruise! The travelers are mainly prisoners; the ships aren’t luxury liners. And the most dreadful part of the trip involves violent, life-threatening storm. Sea voyages were popular in Luke’s day, as reflected in Homer’s famous Odyssey (Bock, 726). Surviving a storm was a mark of great character. Today, many are familiar with the Pirates of the Caribbean movies. Bible readers are also familiar with many storm stories like Jonah, the disciples’ experiences at Galilee (cf., Mark 4:35, 6:45-52), and numerous allusions in the Psalms (Ps 42:7; 66:12; 69:2-3, 15; also Isa 43:2). Luke goes into great detail in this storm story to show what it took for Paul to get to Rome. -

Family Devotions Schedule Spring 2021

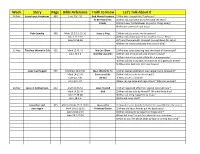

Week Story Page Bible Reference Truth to Know Let's Talk About It 14-Mar Jesus Loves Zacchaeus 403 Luke 19:1-10 God Wants Everyone 1)Why didn't people like Zacchaeus? to Be Part of His 2)What did Zacchaeus do so he could see Jesus? Family 3)Was it easy for Zacchaeus to give his things away? 4)Who can come to know Jesus? Palm Sunday 409 Matt. 21:1-11, 15-16 Jesus is King 1)What did Jesus ride into Jerusalem? Mark 11:1-10 2)What did people put on the road for Jesus? Why? Luke 19:28-38 3)If I was there would I have put my coat down for Jesus? 4)What can I do to celebrate that Jesus is King? 21-Mar The Poor Woman's Gift 415 Mark 12:41-44 We Can Show 1)Who was Jesus watching near the doors of the temple? Luke 21:1-4 God We Love Him 2)What kind of noise did a lot of money make? 3)What kind of noise did a little bit of money make? 4)What did Jesus say about the woman who gave just a little? 5) What does God look for in our hearts? Jesus' Last Supper 419 Matthew 26:17-30 Jesus Wants Us To 1)What special celebration was happening in Jerusalem? Mark 14:12-26 Serve Just Like 2)What did Jesus do for His friends? Luke 22:7-20 He Did 3) Why did Jesus do that? John 13:1-17 4)How can we serve and help others? Who can we help? 28-Mar Jesus in Gethsemane 422 Matt 26:36-50 Jesus Trusted 1)What happened after their special Passover meal? Mark 14:32-46 God 2)What did Jesus do by Himself? Who did He talk to? Luke 22:39-48 3)What sad thing happened to Jesus? John 18:1-9 4)Who did Jesus trust? Jesus Dies and 425 Matt 26:58-68, 27:11-28:10 Jesus is the 1) How -

Leader BIBLE STUDY the Shipwreck

UNIT 34 Session 3 Use Week of: The Shipwreck BIBLE PASSAGE: Acts 27:13-44; 28:11-16 MAIN POINT: God protected Paul in the shipwreck. KEY PASSAGE: Philippians 1:21 BIG PICTURE QUESTION: When should we tell others about Jesus? We should tell about Jesus all the time. INTRODUCE THE STORY TEACH THE STORY EXPERIENCE THE STORY (15–20 MINUTES) (10–15 MINUTES) (20–25 MINUTES) PAGE 34 PAGE 36 PAGE 38 3 Leader BIBLE STUDY Paul was in Roman custody because of unfounded accusations brought against him by the Jews. Paul had stood before rulers in Caesarea and invoked his right as a Roman citizen to appeal to Caesar. So Festus the governor arranged for Paul to go to Rome. Paul got onto a ship going toward Rome. As if Paul’s journey to Rome had not already been delayed and complicated enough, the ship was caught up in a terrible storm. Paul had warned the crew not to sail from Crete because they would lose everything and die. But they didn’t listen. Paul pointed out the error of their ways, but he still gave them hope. An angel had appeared to Paul. He said Preschool Leader Guide 30 Unit 34 • Session 3 © 2018 LifeWay Paul would make it to Rome and all of the people with him would survive. Paul urged everyone on the ship to eat so they would have energy. They planned to run the ship ashore on an island, but the ship got stuck on a sandbar. The waves battered the ship and it broke into pieces; however, all of the people survived and made it safely to shore.