Economic Brief March 2012, EB12-03

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tax Accounting Perspectives ASC 740 Considerations As Income Tax Returns Are Finalized September 28, 2018

Tax Accounting Perspectives ASC 740 considerations as income tax returns are finalized September 28, 2018 Tax provision processes include analyzing the impact of changes for “return-to-provision” items that result when estimates used for the provision are different than amounts reported on income tax returns. Companies should record the tax accounting impact in the period they identify the adjustments and may need to differentiate these from SAB 118 adjustments. What's new? Potential tax expense (or benefit) for adjustments related to temporary What's new differences Potential tax expense (or benefit) The tax accounting impact of return-to-provision (“RTP”) adjustments (also for adjustments related to known as return-to-accrual adjustments or true-ups) should be recorded in the temporary differences period identified. Adjustments may be identified or finalized in the period income tax returns are filed assuming they are not known in an earlier reporting period. For calendar-year companies, returns are due in the fourth quarter and companies finalize RTP adjustments at that time. This timeframe coincides with Highlights the end of the up to one-year measurement period provided by SAB 118 that Analyzing return-to-provision requires final adjustments be recorded for the impact of tax reform. Therefore, adjustments many companies are evaluating both RTP and measurement period adjustments at the same time. After tax reform, adjustments for temporary differences that historically may not have impacted a company’s overall tax expense may now impact a company’s overall tax expense or benefit. For example, a calendar- What does this mean for you year corporation may have a RTP adjustment that increases or decreases Documenting change in estimate current taxes at a 35% rate with the offset to deferred taxes at a 21% rate, ‒ which would impact the overall tax expense. -

Lagged and Contemporaneous Reserve Accounting: an Alternative View

Lagged and Contemporaneous Reserve Accounting: An Alternative View DANIEL L. THORNTON Recently, Feige and McGee presented evidence ECENT volatility in both money and interest that the effect of LEA on federal funds rate volatility has not been substantial when week-to-week relative rates has prompted the Federal Reserve Board to 3 adopt a plan for contemporaneous reserve accounting changes are considered. Thus, previous empirical 1 (CRA). This move follows a number of requests from work on the volatility of short-term imiterest rates under both insideand outside the Federal Reserve System to LEA, which considered longer time periods or abso- return to CRA. These requests stem from empirical lute measures of variability, may be misleading. This investigations that show that both money and interest article presents a theoretical argument to further sup- rates hecame more volatile after the adoption of lagged port this conclusion. It should be emphasized that only reserve accounting (LEA) in September 1968, and the case ofa move from CRA to LEA is considered, hut from theoretical work that shows an increase in volatil- the premise applies equally well to the return to CRA. ity of money and possibly interest rates when the Sys- 2 The outlimie of the article is as follows: First, the tem moves from CRA to LEA. rationale for claiming that the case against LEA is overstated is presented. This idea is then formalized in the context of a simple linear stochastic model of the Daniel L. Thornton is a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. John G. -

Financial Forecasts and Projections 1473

Financial Forecasts and Projections 1473 AT Section 301 Financial Forecasts and Projections Source: SSAE No. 10; SSAE No. 11; SSAE No. 17. Effective when the date of the practitioner’s report is on or after June 1, 2001, unless otherwise indicated. Introduction .01 This section sets forth standards and provides guidance to practition- ers who are engaged to issue or do issue examination (paragraphs .29–.50), compilation (paragraphs .12–.28), or agreed-upon procedures reports (para- graphs .51–.56) on prospective financial statements. .02 Whenever a practitioner (a) submits, to his or her client or others, prospective financial statements that he or she has assembled, or assisted inas- sembling, that are or reasonably might be expected to be used by another (third) party1 or (b) reports on prospective financial statements that are, or reasonably might be expected to be used by another (third) party, the practitioner should perform one of the engagements described in the preceding paragraph. In de- ciding whether the prospective financial statements are or reasonably might be expected to be used by a third party, the practitioner may rely on either the written or oral representation of the responsible party, unless information comes to his or her attention that contradicts the responsible party's represen- tation. If such third-party use of the prospective financial statements is not reasonably expected, the provisions of this section are not applicable unless the practitioner has been engaged to examine, compile, or apply agreed-upon procedures to the prospective financial statements. .03 This section also provides standards for a practitioner who is engaged to examine, compile, or apply agreed-upon procedures to partial presentations. -

Cash Flow Statement

LESSON 7 Cash Flow Statement 1 Financial Accounting 08/09 2ºDE – LESSON 7 © Mª Cristina Abad Navarro, 2009 Outline 7.1. Introduction: definition and purpose. 7.2. Format of the Cash Flow Statement. 7.3. Definition of cash and cash equivalents. 7.4. Cash flows from operating activities. 7.5. Cash flows from investing activities. 7.6. Cash flows from financing activities 2 Financial Accounting 08/09 2ºDE – LESSON 7 © Mª Cristina Abad Navarro, 2009 1 The annual accounts Balance Sheet Income Statement Statement of Changes in Equity Cash Flow Statement Notes to the Financial Statements 3 Financial Accounting 08/09 2ºDE – LESSON 7 © Mª Cristina Abad Navarro, 2009 Statements of financial flows Includes information about: • Financial resources (cash flows) obtained by the firm during the period • Applications of those financial resources (cash flows) Business Operating Purchase of activity activity assets Shareholders’ Distribution of contributions Dividends New debt Payment of debt . Sale of assets . 4 Financial Accounting 08/09 2ºDE – LESSON 7 © Mª Cristina Abad Navarro, 2009 2 Cash Flow Statement The Cash Flow Statement shows: • cash receipts, and • cash payments during the year. These cash receipts and payments explain the changes in the cash account (*) of the Balance Sheet during the year. (*) Cash will include cash and cash equivalents 5 Financial Accounting 08/09 2ºDE – LESSON 7 © Mª Cristina Abad Navarro, 2009 Cash Flow Statement Regulation INTERNATIONAL IAS 7 SPANISH P.G.C. 2007 Is voluntary for: • Companies that can publish abbreviated -

Bank & Financial Institution Modeling

The Provision for Credit Losses & the Allowance for Loan Losses How Much Do You Expect to Lose? This Lesson: VERY Specific to Banks This is about a key accounting topic for banks and financial institutions. It’s only important in that industry. So if you are not interested in banks, you don’t have to watch this (unless you really want to…). Lesson Outline: • Part 1: Allowance for Loan Losses vs. Regulatory Capital • Part 2: Loan Loss Accounting on the Financial Statements • Part 3: Example Scenarios to Illustrate the Mechanics • Part 4: How Regulatory Capital and the Allowance for LLs are Linked Business Model of Commercial Banks • Banks: Collect money from customers (deposits), and then lend it to people who need money (loans) • They expect to lose something on these loans because people and companies default and are unable to pay back their loans • But there are two categories: expected losses and unexpected losses (e.g., a random disaster happens and everyone in a certain region of the country loses everything) • This Tutorial: All about expected losses and how unexpected losses eventually turn into expected losses Expectations Matter! • Poker Scenario: If you bet a lot with no real hand, you should expect to lose everything… and plan accordingly! • But: What happens if you have a Straight Flush and you then do the same thing? Now you expect to win… or at least not lose much • But Then: You keep playing, and it turns out someone else has a Royal Flush – you lose everything you bet! Oops. • First Scenario: Allowance for Loan Losses – Expected Losses • Second Scenario: Regulatory Capital – Unexpected Losses Allowance for Loan Losses on the Statements • Balance Sheet: The Allowance is a contra-asset that’s netted against Gross Loans to calculate Net Loans . -

Operating Reserve: How and Why

Operating Reserve: How and Why Although most nonprofit organizations know that an Operating Reserve is essential, not everyone succeeds in TREC Financial Management Resource Management Financial TREC building one and keeping it. This resource walks through the common obstacles to creating an Operating Reserve and lays out a clear path to achieve it. Definition and Terminology An Operating Reserve is an unrestricted fund balance that is set aside by a nonprofit to assist through unforeseen challenges, help with cash flow shortfalls, and take advantage of unexpected opportunities. In simpler terms, it is a type of savings. An Operating Reserve is sometimes simply referred to as a Reserve Fund. Both of these names are correct. A Reserve Fund is the broader category. Reserve Funds may be split up and named differently on the Statement of Financial Position (Balance Sheet) based upon the intent of the Reserve. For the purposes of this Resource we are using the term Operating Reserve due to its prevalence of use in the nonprofit field and the intended purpose of the fund. After an adequate Operating Reserve is built, other reserve funds can be added. We will discuss different types of reserves further below. Be careful not to confuse net assets with reserves. The balance in the bank accounts is not the same as the reserves. Those balances may include unspent grant money. A reserve is only made up of unrestricted funds and should be explicitly broken out in the equity section of the Statement of Financial Position separate from funds with donor restrictions. Why Have an Operating Reserve Without a clear understanding of why an Operating Reserve benefits the organization, building the will and desire to create one is near impossible. -

Provisions Are Charged As an Expense to the Appropriate Service Line In

Provisions are charged as an expense to the appropriate service line in the Comprehensive Income and Expenditure Statement where an event has taken place that gives the Council a legal or constructive obligation that probably requires settlement by a transfer of economic benefits or service potential, and a reliable estimate can be made of the amount of the obligation. Provisions are charged as the best estimate at the balance sheet date of the expenditure required to settle the obligation, taking into account relevant risks and uncertainties. L. Termination Benefits Termination benefits are charged on an accruals basis to the appropriate service at the earlier of when the Council can no longer withdraw the offer of those benefits or when the Council recognises costs for a restructuring. M. Changes in Accounting Policies Prior period adjustments may arise as a result of a change in accounting policies or to correct a material error. Changes in accounting estimates are accounted for prospectively, i.e. in the current and future years affected by the change and do not give rise to a prior period adjustment. Changes in accounting policies are only made when required by proper accounting practices or the change provides more reliable or relevant information about the effect of transactions, other events and conditions on the Authority’s financial position or financial performance. Where a change is made, it is applied retrospectively (unless stated otherwise) by adjusting opening balances and comparative amounts for the prior period as if the new policy had always been applied. N. Cash and cash equivalents Cash is represented by cash in hand and deposits with financial institutions repayable without penalty on notice of not more than 24 hours. -

RESERVE STUDY GUIDELINES for Homeowner Association Budgets

State of California Department of Real Estate RESERVE STUDY GUIDELINES for Homeowner Association Budgets August 2010 State of California Department of Real Estate RESERVE STUDY GUIDELINES for Homeowner Association Budgets August 2010 This independent research report was developed under contract for the California Department of Real Estate by Eva Eagle, Ph.D., and Susan Stoddard, Ph.D., AICP, Institute for the Study of Family, Work and Community and David H. Levy, M.B.A., C.P.A. Janet Andrews, MBA, was responsible for the original design, layout, and typography. The Department of Real Estate revised this publication in August 2010. It includes updates by Roy Helsing PRA, RS to insure it aligns with current California Law and the guidelines of the Association of Professional Reserve Preparers (APRA) and the Community Associations Institute (CAI).,” The report does not necessarily reflect the position of the Administration of the State of California. NOTE: Before a homeowners’ association decides to prepare its own Reserve Study, it should consider seeking professional advice on that issue. There are issues concerning volunteer board member indemnification, reliance on expert advice, and other factors that should be considered in that decision. The goal of this manual is to help the reader better understand Reserve Studies. It is not the intent of this manual to define the “standard of care” for Reserve Studies or to interpret the California Civil Code. Department of Real Estate . Publications . 2201 Broadway . Sacramento, CA 95818 . Web -

Asset Equipment & Building Reserves

Asset Equipment & Building Reserves MANAGING EQUIPMENT REPLACEMENT AND MAJOR BUILDING MAINTENANCE 6/27/2016 BUSINESS SERVICES 1 Introduction •Changes within the State system of accounting practices have changed the way institution will be accounting for equipment and building reserves going forward. SOU will be beginning with initial implementation in FY2017. •The will be a period of transition from the old model to the new model, after which, the Renewal & Replacement Fund group will be largely phased out. 10/24/2016 BUSINESS SERVICES 2 Agenda •Overview •Definitions •Previous OUS Model. •Previous SOU Modified Model •New SOU Model •Review of Transaction Process using the new SOU Model •Summary 10/24/2016 BUSINESS SERVICES 3 Overview •With the independence of the universities within the State university system, comes with it the ability to make changes to accounting structures. There is still some degree of relationships within the base Fund Structures from university to university, primarily to aid in the preparation of comparable financial statement between universities within the state. •One change occurring between all universities is the phasing out of the Renewal and Replacement Funds. These were largely used to establish reserves for equipment and building maintenance reserves. These will be migrated back to the Current Operating Fund group, as the R&R Fund group is phased out. This document will show the steps that will be taken to accommodate the transition to the new accounting structure for Major Equipment Reserves, and Major Building Replacement Reserves. 10/24/2016 BUSINESS SERVICES 4 Definitions Proprietary Funds = “Unrestricted” funds within Auxiliaries, and Service Centers Non-proprietary Funds = All other funds Major Equipment = Items > $5,000, and a useful life of two years or more. -

The Budget Reconciliation Process: the Senate's “Byrd Rule”

The Budget Reconciliation Process: The Senate’s “Byrd Rule” Updated May 4, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL30862 The Budget Reconciliation Process: The Senate’s “Byrd Rule” Summary Reconciliation is a procedure under the Congressional Budget Act of 1974 by which Congress implements budget resolution policies affecting mainly permanent spending and revenue programs. The principal focus in the reconciliation process has been deficit reduction, but in some years reconciliation has involved revenue reduction generally and spending increases in selected areas. Although reconciliation is an optional procedure, the House and Senate have used it in most years since its first use in 1980 (22 reconciliation bills have been enacted into law and four have been vetoed). During the first several years’ experience with reconciliation, the legislation contained many provisions that were extraneous to the purpose of implementing budget resolution policies. The reconciliation submissions of committees included provisions that had no budgetary effect, that increased spending or reduced revenues when the reconciliation instructions called for reduced spending or increased revenues, or that violated another committee’s jurisdiction. In 1985 and 1986, the Senate adopted the Byrd rule (named after its principal sponsor, Senator Robert C. Byrd) on a temporary basis as a means of curbing these practices. The Byrd rule was extended and modified several times over the years. In 1990, the Byrd rule was incorporated into the Congressional Budget Act of 1974 as Section 313 and made permanent (2 U.S.C. 644). A Senator opposed to the inclusion of extraneous matter in reconciliation legislation may offer an amendment (or a motion to recommit the measure with instructions) that strikes such provisions from the legislation, or, under the Byrd rule, a Senator may raise a point of order against such matter. -

Contingencies and Provisions

U.S. GAAP vs. IFRS: Contingencies and provisions Prepared by: Richard Stuart, Partner, National Professional Standards Group, RSM US LLP [email protected], +1 203 905 5027 February 2020 Introduction Currently, more than 120 countries require or permit the use of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), with a significant number of countries requiring IFRS (or some form of IFRS) by public entities (as defined by those specific countries). Of those countries that do not require use of IFRS by public entities, perhaps the most significant is the U.S. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires domestic registrants to apply U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), while foreign private issuers are allowed to use IFRS as issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (which is the IFRS focused on in this comparison). While the SEC continues to discuss the possibility of allowing domestic registrants to provide supplemental financial information based on IFRS (with a reconciliation to U.S. GAAP), there does not appear to be a specified timeline for moving forward with that possibility. Although the SEC currently has no plans to permit the use of IFRS by domestic registrants, IFRS remains relevant to these entities, as well as private companies in the U.S., given the continued expansion of IFRS use across the globe. For example, many U.S. companies are part of multinational entities for which financial statements are prepared in accordance with IFRS, or may wish to compare themselves to such entities. Alternatively, a U.S. company’s business goals might include international expansion through organic growth or acquisitions. -

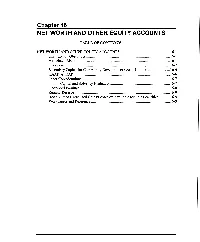

Chapter 16 NET WORTH and OTHER EQUITY ACCOUNTS

Chapter 16 NET WORTH AND OTHER EQUITY ACCOUNTS TABLE OF CONTENTS NET WORTH AND OTHER EQUITY ACCOUNTS .................................................... 16. 1 Examination Objectives ....................................................................................... 16-1 Associated Risks .................................................................................................. 16. 1 Overview ............................................................................................................. .1 6.2 Secondary Capital for Community Development Credit Unions ....................... 16-4 GAAP vs . RAP .................................................................................................... 16-6 Other Considerations ........................................................................................... 16-7 Capital and Solvency Evaluation ............................................................. 16.7 Undivided Earnings ............................................................................................. 16-8 Regular Reserve .................................................................................................... 6-9 Accumulated Unrealized GainsLosses on Available for Sale Securities............ 16-9 Workpapers and References................................................................................. 16-9 Chapter 16 NET WORTH AND OTHER EQUITY ACCOUNTS Examination 0 Determine whether the credit union complies with Regulation D, Objectives if applicable 0 Ascertain compliance with