KWP Titelblaetter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Note-Rostock

Second expert meeting of the Working Group on Marine Geospatial Information Leibniz-Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde, Rostock-Warnemünde, Germany 24 – 28 February 2020 INFORMATION NOTE Introduction This second expert meeting of the Working Group on Marine Geospatial Information seeks to advance its work on data availability, accessibility and interoperability, and to better understand the challenges, opportunities and feasible solutions in making available and accessible marine geospatial information for a multiplicity of applications. The meeting will consider the United Nations Integrated Geospatial Information Framework and its Implementation Guide as a mechanism for articulating and demonstrating national leadership. The meeting will also consider working across the land and sea interface, integrated ecosystems data management practices, capacity and capability development, as well as reviewing and deliberating on its progress and results of its current work plan and activities, new and emerging opportunities, and updating its work plan vis-à-vis the objectives of the Working Group as mandated by the United Nations Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information Management. This second expert meeting is both an administrative and a substantive meeting of the Working Group on Marine Geospatial Information. This second meeting is held in conjunction with the 11th meeting of the Working Group on Marine Spatial Data Infrastructures of the International Hydrographic Organization and the meeting of the Marine Domain Working Group of the Open Geospatial Consortium. Participation is by invitation only. All current members of the Working Group comprising expert representatives of Member States from national geospatial information, mapping or hydrographic authorities, international organizations, UN-GGIM thematic networks and United Nations system are invited. -

Überseehafen Rostock: East Germany’S Window to the World Under Stasi Watch, 1961-1989

Tomasz Blusiewicz Überseehafen Rostock: East Germany’s Window to the World under Stasi Watch, 1961-1989 Draft: Please do not cite Dear colleagues, Thank you for your interest in my dissertation chapter. Please see my dissertation outline to get a sense of how it is going to fit within the larger project, which also includes Poland and the Soviet Union, if you're curious. This is of course early work in progress. I apologize in advance for the chapter's messy character, sloppy editing, typos, errors, provisional footnotes, etc,. Still, I hope I've managed to reanimate my prose to an edible condition. I am looking forward to hearing your thoughts. Tomasz I. Introduction Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski, a Stasi Oberst in besonderen Einsatz , a colonel in special capacity, passed away on June 21, 2015. He was 83 years old. Schalck -- as he was usually called by his subordinates -- spent most of the last quarter-century in an insulated Bavarian mountain retreat, his career being all over three weeks after the fall of the Wall. But his death did not pass unnoticed. All major German evening TV news services marked his death, most with a few minutes of extended commentary. The most popular one, Tagesschau , painted a picture of his life in colors appropriately dark for one of the most influential and enigmatic figures of the Honecker regime. True, Mielke or Honecker usually had the last word, yet Schalck's aura of power appears unparalleled precisely because the strings he pulled remained almost always behind the scenes. "One never saw his face at the time. -

The Baltic German Municipalities´ Inter-Territorial Strategies: a Transition Through City Networks?

Europa Regional 25, 2017 (2018) I 3-4 The Baltic German municipalities´ inter-territorial strategies: a transition through city networks? NICOLAS ESCACH Abstract1 Zusammenfassung Die überstaatlichen Strategien der deutschen Kommu- nen im Ostseeraum: Wandel durch Städtenetzwerke? Since the 1990s, the Baltic region has been undergoing a com- plete reorganization, which is characterized by a type of region- alization often known as “The New Hansa”. The coastline cities Seit den 1990er Jahren befindet sich der Ostseeraum vollständig of Schleswig-Holstein and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, im Wandel, der durch eine Art Regionalisierung gekennzeichnet which lie far from the most dynamic German and European ar- ist, die oft als „Die Neue Hanse“ bezeichnet wird. Die Küsten- eas and often suffer from an economic and demographic decline, städte von Schleswig-Holstein und Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, see in this the chance for a new start. The question is whether die weit entfernt von den dynamischsten deutschen und euro- using the supranational scale and in particular cooperating with päischen Regionen liegen und oft unter wirtschaftlichem und the Øresund regions can enable public and private stakeholders demographischem Rückgang leiden, sehen darin die Chance to offer a real prospect of development to the shrinking cities of für einen Neuanfang. Die Frage ist, ob die Nutzung der staaten- Northern Germany. übergreifenden Dimension und insbesondere die Zusammen- Shrinking Cities; Regionalism; Baltic Sea Region; City-Networks; arbeit mit den Öresund-Regionen es öffentlichen und privaten Rescaling Akteuren ermöglichen kann, den schrumpfenden Städten Nord- deutschlands eine echte Entwicklungsperspektive zu bieten. Schrumpfende Städte; Regionalismus; Ostseeraum; Städtenetz- werke; Neuskalierung 1 The author thanks Anne Raynaud for her precious help. -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

1 the European DTI Study on Dementia

The European DTI Study on Dementia – a multicenter DTI and MRI study on Alzheimer’s disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment Authors: Katharina Brueggena), Michel J. Grothea), Martin Dyrbaa)b), Andreas Fellgiebelc), Florian Fischerc), Massimo Filippid), Federica Agostad), Peter Nestore), Eva Meisenzahlf), Janusch Blautzikg), Lutz Frölichh), Lucrezia Hausnerh), Arun L. W. Bokdei), Giovanni Frisonij), Michela Pievanij), Stefan Klöppelk), David Prvulovicl), Frederik Barkhofm), Petra J. W. Pouwelsm), Johannes Schrödern), Harald Hampelo), Karlheinz Hauensteinp), Stefan Teipela)q) Affiliations: a) DZNE, German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases, Rostock, Germany. b) MMIS group, University of Rostock c) Department of Psychiatry, University Medical Center Mainz, Mainz, Germany d) Neuroimaging Research Unit, Institute of Experimental Neurology, Division of Neuroscience, Scientific Institute and University Vita-Salute San Raffaele, Milano, Italy e) DZNE, German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases, Magdeburg, Germany f) Department of Psychiatry, Ludwig Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany g) Institute for Clinical Radiology, Department of MRI, Ludwig Maximilian University Munich h) Department of Geriatric Psychiatry, Zentralinstitut für Seelische Gesundheit Mannheim, University of Heidelberg, Mannheim, Germany i) Cognitive Systems Group, Discipline of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland; and Trinity College Institute of Neuroscience (TCIN), Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland j) Laboratory of Epidemiology, -

Rostock Port Holds the Course

1 of 6 01/21 15/01/2021 Rostock port holds the course Goods handling on a gratifying high level / slump in passenger traffic A total of 25.1 million tonnes of goods passed the edge of the quay at Rostock Overseas port in 2020. This means a slight decrease by 600,000 tonnes or two percent compared to the result of the previous year. Declines in ferry and ro-ro traffic, for instance in paper and liquid goods handling, were almost completely made up for by increases in dry bulk goods. „Despite the constraints and restrictions at many production companies and in many supply chains which were caused by the pandemic in the course of 2020 the well-balanced business model of the port has once again produced a very high handling result which is close to that of the previous year“, Dr. Gernot Tesch, Managing Director of ROSTOCK PORT GmbH, sums up the result. The volume of infrastructure investment at the overseas port amounted to around €25 million last year. According to Rostock’s Port and Shipping Authority the other ports in Rostock, such as the cargo and fishing port and the chemical port, together handled another 1.6 million tonnes of goods in 2020. This means that, all told, a total of 26.7 million tonnes of cargo were handled in Rostock last year. Only a little more than half the number of passengers compared to the previous year were counted on the ferry lines to northern Europe, at 1.37 million. There was only one port call by a passenger vessel with 200 travellers at the Warnemünde cruise port. -

Supplementary Materials Visualization of Polymer Crystallization by in Situ Combination of Atomic Force Microscopy and Fast Scanning Calorimetry

Supplementary Materials Visualization of Polymer Crystallization by in situ Combination of Atomic Force Microscopy and Fast Scanning Calorimetry Rui Zhang 1, Evgeny Zhuravlev 1, 2, 3*, René Androsch 4 and Christoph Schick 1, 5 1 Institute of Physics and Competence Centre CALOR, University of Rostock, 18051 Rostock, Germany; [email protected] 2 Department of Polymer Science and Engineering, School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Key Laboratory of High-Performance Polymer Materials and Technology of Ministry of Education, and The State Key Laboratory of Coordination Chemistry, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, P. R. China; [email protected] 3 Sheyang Research Institute, Nanjing University, Sheyang, 224300, P. R. China; [email protected] 4 Interdisciplinary Center for Transfer-oriented Research in Natural Sciences (IWE TFN), Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, 06099 Halle/Saale; [email protected] 5 Butlerov Institute of Chemistry, Kazan Federal University, 18 Kremlyovskaya street, Kazan 420008, Russian Federation; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Supplementary materials includes images, that authors decided not to include in the main text, but may be useful for readers, interested in particular details. A.1 Increase of accessible area for AFM Improved Z-range of the used AFM was reached by optimizing reference amplitude setting area. The result of optimization can be seen from Figure S1. (a) (b) 23 μm (c) (d) 36 μm Figure S1. AFM images of PA 66 showing the increase of accessible area. Imaging using sample center (green square) to set the reference amplitude – a and b. Imaging using optimized area (yellow square) to set the reference amplitude – c and d. -

Service Impacts (As of July 15Th, 2021)

Service impacts (as of July 15th, 2021) Potential service impact due to FedEx/TNT related industrial action in France French trade unions have called an industrial action on all our sites in France which has started today, July 15. Impacts are to be expected on the following: � French domestic services: pick-ups, deliveries and transit times are likely to be affected nationwide for domestic shipments moving within France. � International services to and from France: pick-ups, deliveries and transit times for shipments from France to Europe and rest of world, as well as shipments from rest of world and Europe to France will also likely be impacted. � Both FedEx and TNT, parcel, freight, Express and Economy service options are impacted. In the meantime, we advise our customers in France to hold their shipments whenever possible until Monday, July 19. Please note that Charles de Gaulle Hub activities (transit activities) are not affected. Shipments from origins and destinations other than France that transit through the Charles de Gaulle Hub are not expected to be impacted. Transit time changes impacting TNT services – 2/7/2021 We are updating the transit times for Intra-European and Intercontinental shipments as of July 5. Customers using our TNT Economy services will have one extra day to quoted transit times. Transit quotation tools and online shipping applications will be updated on July 5 to reflect these changes. Origins and destinations impacted as shown below: Product From countries or regions To countries or regions TNT Economy -

List of Participating Centers

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA List of participating centers Aachen – Innere RWTH; Aachen – Uni-Kinderklinik RWTH; Aalen Kinderklinik; Ahlen St. Franziskus Kinderklinik; Aidlingen Praxisgemeinschaft; Altötting Zentrum Inn-Salzach; Altötting-Burghausen Innere Medizin; Amstetten Klinikum Mostviertel Kinderklinik; Arnsberg-Hüsten Karolinenhospital Kinderabteilung; Asbach Kamillus-Klinik Innere; Aue Helios Kinderklink; Augsburg Innere; Augsburg Kinderklinik Zentralklinikum; Aurich Kinderklinik; Bad Aibling Internistische Praxis; Bad Driburg / Bad Hermannsborn Innere; Bad Hersfeld Innere; Bad Hersfeld Kinderklinik; Bad Kreuznach-St. Marienwörth-Innere; Bad Kreuznach-Viktoriastift; Bad Krozingen Klinik Lazariterhof Park-Klinikum; Bad Kösen Kinder-Rehaklinik; Bad Lauterberg Diabeteszentrum Innere; Bad Mergentheim – Diabetesfachklinik; Bad Mergentheim – Gemeinschaftspraxis DM-dorf Althausen; Bad Oeynhausen Herz-und Diabeteszentrum NRW; Bad Orb Spessart Klinik; Bad Orb Spessart Klinik Reha; Bad Reichenhall Kreisklinik Innere Medizin; Bad Salzungen Kinderklinik; Bad Säckingen Hochrheinklinik Innere; Bad Waldsee Kinderarztpraxis; Bautzen Oberlausitz KK; Bayreuth Innere Medizin; Berchtesgaden CJD; Berchtesgaden MVZ Innere Medizin; Berlin DRK-Kliniken; Berlin Endokrinologikum; Berlin Evangelisches Krankenhaus Königin Elisabeth; Berlin Klinik St. Hedwig Innere; Berlin Lichtenberg – Kinderklinik; Berlin Oskar Zieten Krankenhaus Innere; Berlin Parkklinik Weissensee; Berlin Schlosspark-Klinik Innere; Berlin St. Josephskrankenhaus Innere; Berlin Virchow-Kinderklinik; -

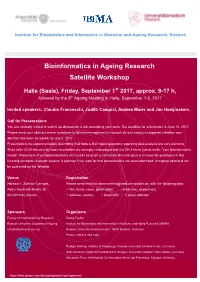

Bioinformatics in Ageing Research Satellite Workshop

Institute for Biostatistics and Informatics in Medicine and Ageing Research, Rostock Bioinformatics in Ageing Research Satellite Workshop Halle (Saale), Friday, September 1st 2017, approx. 9-17 h, followed by the 8th Ageing Meeting in Halle, September 1-3, 2017 Invited speakers: Claudio Franceschi, Judith Campisi, Andrea Maier and Jan Hoeijmakers. Call for Presentations You are cordially invited to submit an abstract for a talk describing your work. The deadline for submission is June 15, 2017. Please send your abstract and/or questions to [email protected] and expect a response (whether your abstract has been accepted) by July 1, 2017. Presentations by experimentalists describing their data & their open questions regarding data analysis are very welcome. Short talks (5-20 minutes) by experimentalists are strongly encouraged and it is OK if these just describe "your bioinformatics needs". Presenters of accepted abstracts will usually be given a 20-minute time slot (plus 5 minutes for questions) in the meeting schedule. A poster session is planned if the slots for oral presentations are oversubscribed. Accepted abstracts will be published on the Website. Venue Registration Hörsaal 1, Steintor-Campus, Please send email to [email protected], with the following data: Adam-Kuckhoff-Straße 35, + title, family name, given name + institution, department 06120 Halle (Saale) + address, country + telephone + email address Sponsors Organizers Faculty of Interdisciplinary Research, Georg Fuellen Rostock University (Department Ageing Institute for Biostatistics and Informatics in Medicine and Aging Research (IBIMA) of individuals and society) Rostock University Medical Center, 18057 Rostock, Germany Phone: +49 381 494 7360 Rüdiger Köhling, Institute of Physiology, Rostock University, Medical Center, Germany Andreas Simm, Clinic for Cardiothoracic Surgery, University Hospital, Halle (Saale), Germany Alexander Tietz, Gesellschaft für Gesundes Altern und Prävention, Cologne, Germany https://sites.google.com/site/ageingbioinfo/ageingbioinfo2 . -

Appreciating Concerns of Host Country Population Improves Attitudes Towards Immigrants

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12630 Conflicting Identities: Cosmopolitan or Anxious? Appreciating Concerns of Host Country Population Improves Attitudes Towards Immigrants Tobias Stöhr Philipp Wichardt SEPTEMBER 2019 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12630 Conflicting Identities: Cosmopolitan or Anxious? Appreciating Concerns of Host Country Population Improves Attitudes Towards Immigrants Tobias Stöhr Kiel Institute for the World Economy and IZA Philipp Wichardt Universität Rostock SEPTEMBER 2019 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. ISSN: 2365-9793 IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 12630 SEPTEMBER 2019 ABSTRACT Conflicting Identities: Cosmopolitan or Anxious? Appreciating Concerns of Host Country Population Improves Attitudes Towards Immigrants This paper connects insights from the literature on cosmopolitan values in political science, anxiety in social psychology, and identity economics in a vignette-style experiment. -

Keel-Laying for Aidacosma at Neptun Werft Shipyard in Rostock AIDA's

Keel-laying for AIDAcosma at Neptun Werft Shipyard in Rostock AIDA’s second LNG cruise ship to sail from Kiel to Norway and the Baltic Sea in summer 2021. October 15, 2019 On October 15, 2019, the first building-block for AIDA Cruises’ second LNG-powered cruise ship was put in place at the Neptun Werft shipyard in Rostock. The two trainees, Charleen Hoffmann (AIDA Cruises) and Kenny Schaft (Meyer Werft shipyard) placed the traditional lucky coin beneath the first of a total of 90 blocks. On the occasion of the keel-laying, the name of the new ship and its first routing were announced: the ship will be named AIDAcosma, and will be cruising from Kiel to the Norwegian fjords and the Baltic Sea from summer 2021. Together with the Managing Director of the Meyer Werft shipyard Tim Meyer and the head of the Neptun Werft shipyard in Rostock Manfred Ossevorth, AIDA President Felix Eichhorn welcomed numerous guests from the worlds of politics and business including Birgit Hesse, President of the Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania state parliament, Rostock’s Mayor Claus Ruhe Madsen, and the President of Rostock’s municipal assembly Regine Lück. In his speech Harry Glawe, the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Minister for Economics, Construction and Tourism emphasized the importance of this maritime location on the Warnow, and praised AIDA Cruises for its great commitment. AIDA President Felix Eichhorn: “With AIDAcosma we are consistently continuing our sustainable growth. The keel-laying of our second LNG-powered cruise ship here in Rostock is also an expression of our company’s economic and innovative power in Rostock and throughout northern Germany.” In 2018 AIDA Cruises alone contributed over 1.6 billion Euros to northern Germany’s economic growth.